2015-2019 Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

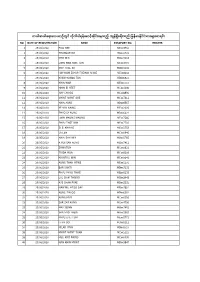

Relief Flight Waiting List As of 16-8-2020.Pdf

ကယ်ဆယ်ေရးေလယာ်တငွ ် လိုက်ပါရန်ေစာင့်ဆိုင်းေနသည့် ကျန်ရှိခရီးသည် ြမန်မာိုင်ငသံ ားများစာရငး် NO DATE OF REGISTRATION NAME PASSPORT NO. REMARK 1 29/06/2020 PAAI KEE MExx4532 2 29/06/2020 THANDAR OO MDxx2722 3 29/06/2020 MYO WIN MDxx9044 4 29/06/2020 LWIN NWE NWE TUN MExx4774 5 29/06/2020 MAY THAE SU MDxx1141 6 29/06/2020 HAY MAM ZAYAR THEINGI SHWE MExx8653 7 29/06/2020 KYAW NANDA TUN MBxx6921 8 29/06/2020 KHIN WAR MExx1747 9 29/06/2020 HNIN EI HTET MCxx4340 10 29/06/2020 NAY CHI OO MCxx8896 11 29/06/2020 MYINT MYINT SOE MCxx7311 12 29/06/2020 KHIN AUNG MDxx8567 13 29/06/2020 YE WIN NAING MExx2325 14 29/06/2020 PHYO SY AUNG MDxx6022 15 29/06/2020 LWIN MAUNG MAUNG MExx7666 16 29/06/2020 PHYU THET WIN MFxx7703 17 29/06/2020 EI EI KHAING MExx1753 18 29/06/2020 JA LEN MCxx0846 19 29/06/2020 KHIN SAN WIN MDxx5766 20 29/06/2020 K ROI SAN AUNG MBxx7412 21 29/06/2020 ZAWHTUN MCxx0821 22 29/06/2020 THIDA MON MCxx8358 23 29/06/2020 KHINTHU WIN MCxx5641 24 29/06/2020 AUNG THAN HTWE MExx1276 25 29/06/2020 BAR SANTI MDxx7131 26 29/06/2020 PHYU PHYU THWE MBxx8235 27 29/06/2020 LAL SIAM THANGI MBxx3043 28 29/06/2020 AYE CHAN PYAE MDxx3332 29 29/06/2020 NAW MU HTOO GAY MBxx7501 30 29/06/2020 AUNG ZIN OO MDxx6002 31 29/06/2020 AUNG MYO MCxx6356 32 29/06/2020 ZAR ZAR AUNG MExx4750 33 29/06/2020 MAY SEINN MBxx7481 34 29/06/2020 WIN MYO THEIN MAxx9583 35 29/06/2020 PHYU EI EI TUN MExx0772 36 29/06/2020 HTAY OO MBxx0212 37 29/06/2020 NILAR HTAY MDxx8727 38 29/06/2020 MYINT MYINT THAN MExx5122 39 29/06/2020 HSU MYO PAING MCxx0090 40 29/06/2020 NAN KHIN MYINT MBxx9847 NO DATE OF REGISTRATION NAME PASSPORT NO. -

University of Yangon Department of Anthropology

UNIVERSITY OF YANGON DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCATION IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYIN TOWNSHIP, YANGON SOE MOE NAiNG M.A. Antb.6 (2009-2010) YANGON MAY,20tO UNIVERSITY OF YANGON DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCATION IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYINTOWNSHIP, YANGON SOE MOE NAING M.A. Anth.6 (2009-2010) YANGON MAY,2010 UNIVERSITY OF YANGON DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCAnON IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYIN TOWNSHIP, YANGON Research Thesis is submitted for Master Degree in Anthropology Submitted By SOE MOE NAING M.A. Anth.6 ( 2009- 2010 ) YANGON 2010 EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCATION IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYIN TOWNSHIP, YANGON EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCATION IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYINTOWNSHlP, YANGON SOE MOE NAING M.A. Anth.6 ( 2009- 2010 ) Master Degree in Anthropology Department of Anthropology May. 2010 proved by Board of Examiners -.1:fl'-"'J'G k,J ~D:p\(\'" ............~~~. .. .... .... .. ?f.l~ . Chairperson External Examiner (Mya Mya Khln.Dr.] ( Myint Myint Aye) Associate Professor/Head Lecturer! Head Departmentof Anthropology Department ofAnthropology University ofYangon University of Dagon Supervisor Co-supervisor ( Mya Thidar Aung) ( Zin Mar Latt ) Department of Anthropology Department ofAnthropology University of Yangon University of Yangon Contents No. Particular Page Acknowledgements Abstract Key words Introduction Chapter (I) Research Methodology Data Collection 0). Key Informant Interview (ii). Interview (iii). Focus Group Interview Data Analysis 2 Chapter (II) Background Research Area 3 (I). History of Sitpinquin Village 3 (2). Geographical Selling 4 (3). Communication and Transportation 4 (4). Population 5 (5). Pattern ofHousing 6 (6). Operational Definition 6 Chapter (tIl) Education 8 (1). Local Perception on Education 8 (2). -

Election Monitor No.49

Euro-Burma Office 10 November 22 November 2010 Election Monitor ELECTION MONITOR NO. 49 DIPLOMATS OF FOREIGN MISSIONS OBSERVE VOTING PROCESS IN VARIOUS STATES AND REGIONS Representatives of foreign embassies and UN agencies based in Myanmar, members of the Myanmar Foreign Correspondents Club and local journalists observed the polling stations and studied the casting of votes at a number of polling stations on the day of the elections. According the state-run media, the diplomats and guests were organized into small groups and conducted to the various regions and states to witness the elections. The following are the number of polling stations and number of eligible voters for the various regions and states:1 1. Kachin State - 866 polling stations for 824,968 eligible voters. 2. Magway Region- 4436 polling stations in 1705 wards and villages with 2,695,546 eligible voters 3. Chin State - 510 polling stations with 66827 eligible voters 4. Sagaing Region - 3,307 polling stations with 3,114,222 eligible voters in 125 constituencies 5. Bago Region - 1251 polling stations and 1057656 voters 6. Shan State (North ) - 1268 polling stations in five districts, 19 townships and 839 wards/ villages and there were 1,060,807 eligible voters. 7. Shan State(East) - 506 polling stations and 331,448 eligible voters 8. Shan State (South)- 908,030 eligible voters cast votes at 975 polling stations 9. Mandalay Region - 653 polling stations where more than 85,500 eligible voters 10. Rakhine State - 2824 polling stations and over 1769000 eligible voters in 17 townships in Rakhine State, 1267 polling stations and over 863000 eligible voters in Sittway District and 139 polling stations and over 146000 eligible voters in Sittway Township. -

Field Survey and Collection of Traditionally Grown Crops in Northern Areas of Myanmar, 2006

〔植探報 Vol. 23 : 161 ~ 175,2007〕 ミャンマー北部における伝統的作物の調査と収集(2006年) 渡邉 和男 1)・YE TINT TUN 2)・河瀨 眞琴 3) 1) 筑波大学大学院・生命環境科学研究科 2) ミャンマー農業灌漑省・ミャンマー農業公社 3) 農業生物資源研究所・ジーンバンク Field Survey and Collection of Traditionally Grown Crops in Northern Areas of Myanmar, 2006 Kazuo WATANABE1), Ye Tint Tun2) and Makoto KAWASE3) 1) Graduate School of Life and Environment Sciences, Tsukuba University, 1-1-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan 2) Myanma Rice Research Institute, Myanma Agriculture Service, Hmowbi, Yangon, Myanmar, 3) Genebank, National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8602, Japan Summary Myanmar has been suggested to harbor genetic diversity of wild and cultivated rice and several other cultivated plants. Systematic field survey and collection of plant genetic resources were, however, not so intensively organized there. A limited number of explorations were organized by IRRI in early 1990s, by JICA Seedbank Project during 1997 to 2002, and by NIAS Genebank Project from 1999 to 2005. A field exploration was planned and carried out to investigate and collect genetic variation of upland rice, small millets, pulses, ginger and turmeric in Kachin State in cooperation of scientists of Tsukuba University (Japan), National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences (Japan) and the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (Myanmar) from November 14 to December 1, 2006. This field research was funded by a Grand-in-Aid for Overseas Scientific Research of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. Even though our botanical trip was not so smoothly carried out as planned mainly due to severe road conditions caused by unexpected weather, we successfully surveyed a wide range of areas in Kachin State, and collected 90 samples of plant genetic resources. -

Assistant Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) Email: Info

Assistant Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) No. Name Prisoner No. Father's Name Section of Law Setenced Organization Prison Address Date of Date of Arrest Release 1 Aung Tun N/A N/A N/A NLD N/A Thingangyun,Ra 26-Mar-07 26-Mar-07 ngoon 2 Htein Lin Kyaw N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Rangoon 26-Mar-07 26-Mar-07 3 Min Zaw Oo N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Rangoon 26-Mar-07 26-Mar-07 4 Ohmar N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Rangoon 26-Mar-07 26-Mar-07 5 Cho Cho Lwin (F) N/A N/A N/A N/A Parlami Sanchaung, 22-Aug-07 22-Aug-07 Junction Rangoon 6 Kyin Yee (F) N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Dala, Rangoon 22-Aug-07 22-Aug-07 7 San San Myint (F) N/A N/A N/A N/A Parlami Dala, Rangoon 22-Aug-07 22-Aug-07 Junction 8 Than Zaw Myint N/A N/A N/A N/A Parlami Hlaing Tharyar, 22-Aug-07 22-Aug-07 Junction Rangoon 9 Tin Maung Yee N/A N/A N/A N/A Parlami Hlaing, Rangoon 22-Aug-07 22-Aug-07 Junction 10 Yin Yin Myat (F) N/A N/A N/A N/A Parlami Thingangyun, 22-Aug-07 22-Aug-07 Junction Rangoon 11 Aung Kyaw Oo N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 23-Aug-07 24-Aug-07 12 Aye Aye Tun (F) N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Sanchaung, 23-Aug-07 24-Aug-07 Rangoon 13 Gyo Gyo N/A N/A N/A Hledan traffic N/A N/A N/A 28-Aug-07 point In Rangoon. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

Political Monitor No.7

Euro-Burma Office 20 March – 1 April 2016 Political Monitor 2016 POLITICAL MONITOR NO. 7 OFFICIAL MEDIA MYANMAR ENTERS NEW ERA President Htin Kyaw took his oath of office at the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw on 30 March. In his inaugural speech, he said his government will strive to amend the current constitution. “I am responsible for the emergence of a constitution that will be in accord with the democratic norms suited to our country. I am also aware that I need to be patient in realising this political objective, for which the people have long aspired,” said the president. He said his government will seek to implement four policies: national reconciliation; internal peace; the emergence of a constitution that will produce a democratic, federal union; and the improvement of the quality of life of the majority of the people. Following the swearing-in ceremony at the parliament, a ceremony marking the handover of presidential duties from out-going President Thein Sein to incoming President Htin Kyaw was held at the Credentials Hall of the Presidential Palace in Nay Pyi Taw. The two vice presidents, Myint Swe and Henry Van Thio as well as the new government ministers were also sworn in on 30 March in Nay Pyi Taw. (Please see Appendix A for full text of the President Htin Kyaw’s inaugural speech).1 NLD CREATES TO “STATE COUNCILLOR” ROLE FOR AUNG SAN SUU KYI The Amyotha Hluttaw (Upper House) agreed on 31 March to discuss a special bill that would create the post of the State Counsellor for NLD Chair Aung San Suu Kyi in the new cabinet. -

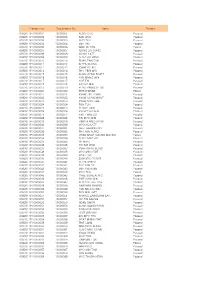

Recent Arrests List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 8 of the Export and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Import Law and S: 25 Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and of the Natural Disaster Lin of Special Branch regions were also detained. Management law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 25 of the Natural President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Naing law regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and parliament regions were also detained. -

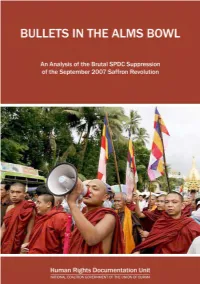

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

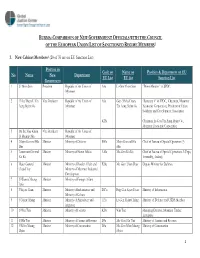

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

Primary Key Registration No. Name Remark 0092011P10000001

Primary Key Registration No. -

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February

2008R0194 — EN — 21.12.2011 — 009.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 66, 10.3.2008, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 L 116 5 30.4.2008 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 L 108 20 29.4.2009 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 747/2009 of 14 August 2009 L 212 10 15.8.2009 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1267/2009 of 18 December 2009 L 339 24 22.12.2009 ►M5 Council Regulation (EU) No 408/2010 of 11 May 2010 L 118 5 12.5.2010 ►M6 Commission Regulation (EU) No 411/2010 of 10 May 2010 L 118 10 12.5.2010 ►M7 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 383/2011 of 18 April L 103 8 19.4.2011 2011 ►M8 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 891/2011 of 1 L 230 1 7.9.2011 September 2011 ►M9 Council Regulation (EU) No 1083/2011 of 27 October 2011 L 281 1 28.10.2011 ►M10 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1345/2011 of 19 December L 338 19 21.12.2011 2011 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. 74 (385/2008) 2008R0194 — EN — 21.12.2011 — 009.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN