State-And-Region-Gov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2003/297/CFSP of 28 April 2003 on Burma/Myanmar

L 106/36EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2003 (Acts adopted pursuant to Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2003/297/CFSP of 28 April 2003 on Burma/Myanmar THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, will not be imposed if by that time there is substantive progress towards national reconciliation, the restoration of a democratic order and greater respect for human Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in parti- rights in Burma/Myanmar. cular Article 15 thereof, (6) Exemptions should be introduced in the arms embargo Whereas: in order to allow the export of certain military rated equipment for humanitarian use. (1) On 28 October 1996, the Council adopted Common Position 96/635/CFSP on Burma/Myanmar (1), which (7) The implementation of the visa ban should be without expires on 29 April 2003. prejudice to cases where a Member State is bound by an obligation of international law, or is host country of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (2) In view of the further deterioration in the political situa- (OSCE), or where the Minister and Vice-Minister for tion in Burma/Myanmar, as witnessed by the failure of Foreign Affairs for Burma/Myanmar visit with prior noti- the military authorities to enter into substantive discus- fication and agreement of the Council. sions with the democratic movement concerning a process leading to national reconciliation, respect for human rights and democracy and the continuing serious (8) The implementation of the ban on high level visits at the violations -

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

B U R M a B U L L E T

B U R M A B U L L E T I N ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞A month-in-review of events in Burma∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ A L T E R N A T I V E A S E A N N E T W O R K O N B U R M A campaigns, advocacy & capacity-building for human rights & democracy Issue 20 August 2008 • Fearing a wave of demonstrations commemorating th IN THIS ISSUE the 20 anniversary of the nationwide uprising, the SPDC embarks on a massive crackdown on political KEY STORY activists. The regime arrests 71 activists, including 1 August crackdown eight NLD members, two elected MPs, and three 2 Activists arrested Buddhist monks. 2 Prison sentences • Despite the regime’s crackdown, students, workers, 3 Monks targeted and ordinary citizens across Burma carry out INSIDE BURMA peaceful demonstrations, activities, and acts of 3 8-8-8 Demonstrations defiance against the SPDC to commemorate 8-8-88. 4 Daw Aung San Suu Kyi 4 Cyclone Nargis aid • Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is allowed to meet with her 5 Cyclone camps close lawyer for the first time in five years. She also 5 SPDC aid windfall receives a visit from her doctor. Daw Suu is rumored 5 Floods to have started a hunger strike. 5 More trucks from China • UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Burma HUMAN RIGHTS 5 Ojea Quintana goes to Burma Tomás Ojea Quintana makes his first visit to the 6 Rape of ethnic women country. The SPDC controls his meeting agenda and restricts his freedom of movement. -

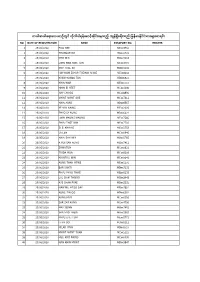

Relief Flight Waiting List As of 16-8-2020.Pdf

ကယ်ဆယ်ေရးေလယာ်တငွ ် လိုက်ပါရန်ေစာင့်ဆိုင်းေနသည့် ကျန်ရှိခရီးသည် ြမန်မာိုင်ငသံ ားများစာရငး် NO DATE OF REGISTRATION NAME PASSPORT NO. REMARK 1 29/06/2020 PAAI KEE MExx4532 2 29/06/2020 THANDAR OO MDxx2722 3 29/06/2020 MYO WIN MDxx9044 4 29/06/2020 LWIN NWE NWE TUN MExx4774 5 29/06/2020 MAY THAE SU MDxx1141 6 29/06/2020 HAY MAM ZAYAR THEINGI SHWE MExx8653 7 29/06/2020 KYAW NANDA TUN MBxx6921 8 29/06/2020 KHIN WAR MExx1747 9 29/06/2020 HNIN EI HTET MCxx4340 10 29/06/2020 NAY CHI OO MCxx8896 11 29/06/2020 MYINT MYINT SOE MCxx7311 12 29/06/2020 KHIN AUNG MDxx8567 13 29/06/2020 YE WIN NAING MExx2325 14 29/06/2020 PHYO SY AUNG MDxx6022 15 29/06/2020 LWIN MAUNG MAUNG MExx7666 16 29/06/2020 PHYU THET WIN MFxx7703 17 29/06/2020 EI EI KHAING MExx1753 18 29/06/2020 JA LEN MCxx0846 19 29/06/2020 KHIN SAN WIN MDxx5766 20 29/06/2020 K ROI SAN AUNG MBxx7412 21 29/06/2020 ZAWHTUN MCxx0821 22 29/06/2020 THIDA MON MCxx8358 23 29/06/2020 KHINTHU WIN MCxx5641 24 29/06/2020 AUNG THAN HTWE MExx1276 25 29/06/2020 BAR SANTI MDxx7131 26 29/06/2020 PHYU PHYU THWE MBxx8235 27 29/06/2020 LAL SIAM THANGI MBxx3043 28 29/06/2020 AYE CHAN PYAE MDxx3332 29 29/06/2020 NAW MU HTOO GAY MBxx7501 30 29/06/2020 AUNG ZIN OO MDxx6002 31 29/06/2020 AUNG MYO MCxx6356 32 29/06/2020 ZAR ZAR AUNG MExx4750 33 29/06/2020 MAY SEINN MBxx7481 34 29/06/2020 WIN MYO THEIN MAxx9583 35 29/06/2020 PHYU EI EI TUN MExx0772 36 29/06/2020 HTAY OO MBxx0212 37 29/06/2020 NILAR HTAY MDxx8727 38 29/06/2020 MYINT MYINT THAN MExx5122 39 29/06/2020 HSU MYO PAING MCxx0090 40 29/06/2020 NAN KHIN MYINT MBxx9847 NO DATE OF REGISTRATION NAME PASSPORT NO. -

Democratization in Myanmar: Prospects, Possibilities and Challenges Md

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) Volume 4 Issue 5, July-August 2020 Available Online: www.ijtsrd.com e-ISSN: 2456 – 6470 Democratization in Myanmar: Prospects, Possibilities and Challenges Md. Abdul Hannan Lecturer, Department of International Relations, Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP), Dhaka, Bangladesh ABSTRACT How to cite this paper: Md. Abdul This paper endeavors to provide a comprehensive overview of the Hannan "Democratization in Myanmar: democratization process in Myanmar. As today’s reality in Myanmar cannot be Prospects, Possibilities and Challenges" well understood without referral to its history of democratic struggle, it starts Published in with a brief history of Myanmar that gives an account of several significant International Journal incidents that the country experienced from the pre-independence period to of Trend in Scientific the last democratic election in 2015. The next section discusses about some Research and specific features of the incumbent government of Myanmar which gives an Development understanding of how much democratic the government has been actually. In (ijtsrd), ISSN: 2456- the subsequent section, identifying some important areas whose proper 6470, Volume-4 | IJTSRD33125 management or utilization can take the democracy in Myanmar to the next Issue-5, August level, it concludes. 2020, pp.1368-1372, URL: www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd33125.pdf KEYWORDS: democracy, military, ethnic-groups, media, human-rights groups Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development Journal. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by /4.0) INTRODUCTION Democracy, by many, is said to be the best form of twenty five percent preserved seats for the military in the government to install and sustain peace and stability in both parliament, requirement of more than 75 percent domestic and international spheres. -

Proposals for Constitutional Change in Myanmar from the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Constitutional Amendment International Idea Interim Analysis

PROPOSALS FOR CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE IN MYANMAR FROM THE JOINT PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEE ON CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT INTERNATIONAL IDEA INTERIM ANALYSIS 1. Background, Purpose and Scope of this Report: On 29 January Myanmar’s Parliament voted to establish a committee to review the constitution and receive proposals for amendments. On July 15 a report containing a catalogue of each of these proposals was circulated in the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (Union Legislature). This International IDEA analysis contains an overview and initial assessment of the content of these proposals. From the outset, the Tatmadaw (as well as the Union Solidarity and Development Party - USDP) has objected to this process of constitutional review,i and unless that opposition changes it would mean that the constitutional review process will not be able to proceed much further. Passing a constitutional amendment requires a 75% supermajority in the Union Legislature, which gives the military an effective veto as they have 25% of the seats.1 Nevertheless, the report provides the first official public record of proposed amendments from different political parties, and with it a set of interesting insights into the areas of possible consensus and divergence in future constitutional reform. The importance of this record is amplified by the direct connection of many of the subjects proposed for amendment to the Panglong Peace Process agenda. Thus far, the analyses of this report available publicly have merely counted the number of proposals from each party, and sorted them according to which chapter of the constitution they pertain to. But simply counting proposals does nothing to reveal what changes are sought, and can be misleading – depending on its content, amending one significant article may bring about more actual change than amending fifty other articles. -

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25

2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 66, 10.3.2008, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 L 116 5 30.4.2008 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 L 108 20 29.4.2009 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 747/2009 of 14 August 2009 L 212 10 15.8.2009 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1267/2009 of 18 December 2009 L 339 24 22.12.2009 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. 74 (385/2008) 2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Articles 60 and 301 thereof, Having regard to Common Position 2007/750/CFSP of 19 November 2007 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar (1), Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Whereas: (1) On 28 October 1996, the Council, concerned at the absence of progress towards democratisation and at the continuing violation of human rights in Burma/Myanmar, imposed certain restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar by Common Position 1996/635/CFSP (2). -

Election Monitor No.49

Euro-Burma Office 10 November 22 November 2010 Election Monitor ELECTION MONITOR NO. 49 DIPLOMATS OF FOREIGN MISSIONS OBSERVE VOTING PROCESS IN VARIOUS STATES AND REGIONS Representatives of foreign embassies and UN agencies based in Myanmar, members of the Myanmar Foreign Correspondents Club and local journalists observed the polling stations and studied the casting of votes at a number of polling stations on the day of the elections. According the state-run media, the diplomats and guests were organized into small groups and conducted to the various regions and states to witness the elections. The following are the number of polling stations and number of eligible voters for the various regions and states:1 1. Kachin State - 866 polling stations for 824,968 eligible voters. 2. Magway Region- 4436 polling stations in 1705 wards and villages with 2,695,546 eligible voters 3. Chin State - 510 polling stations with 66827 eligible voters 4. Sagaing Region - 3,307 polling stations with 3,114,222 eligible voters in 125 constituencies 5. Bago Region - 1251 polling stations and 1057656 voters 6. Shan State (North ) - 1268 polling stations in five districts, 19 townships and 839 wards/ villages and there were 1,060,807 eligible voters. 7. Shan State(East) - 506 polling stations and 331,448 eligible voters 8. Shan State (South)- 908,030 eligible voters cast votes at 975 polling stations 9. Mandalay Region - 653 polling stations where more than 85,500 eligible voters 10. Rakhine State - 2824 polling stations and over 1769000 eligible voters in 17 townships in Rakhine State, 1267 polling stations and over 863000 eligible voters in Sittway District and 139 polling stations and over 146000 eligible voters in Sittway Township. -

Situation Analysis of Myanmar's Region and State Hluttaws

1 Authors This research product would not have been possible without Carl DeFaria the great interest and cooperation of Hluttaw and government representatives in Mon, Mandalay, Shan and Tanintharyi Philipp Annawitt Region and States. We would like express our heartfelt thanks to Daw Tin Ei, Speaker of the Mon State Hluttaw, U Aung Kyaw Research Team Leader Oo, Speaker of the Mandalay Region Hluttaw, U Sai Lone Seng, Aung Myo Min Speaker of the Shan State Hluttaw, and U Khin Maung Aye, Speaker of the Tanintharyi Region Hluttaw, who participated enthusiastically in this project and made themselves, their Researcher and Technical Advisor MPs and staff available for interviews, and who showed great Janelle San ownership throughout the many months of review and consultation on the findings and resulting recommendations. We also wish to thank Chief Ministers U Zaw Myint Maung, Technical Advisor Dr Aye Zan, U Linn Htut, and Dr. Le Le Maw for making Warren Cahill themselves and/or their ministers and cabinet members available for interviews, and their Secretaries of Government who facilitated travel authorizations and set up interviews Assistant Researcher with township officials. T Nang Seng Pang In particular, we would like to thank the eight constituency Research Team Members MPs interviewed for this research who took several days out of their busy schedule to organize and accompany our research Hlaing Yu Aung team on visits to often remote parts of their constituencies Min Lawe and organized the wonderful meetings with ward and village tract administrators, household heads and community Interpreters members that proved so insightful for this research and made our picture of the MP’s role in Region and State governance Dr. -

Constitution of Myanmar the Constitution of The

CONSTITUTION OF MYANMAR THE CONSTITUTION OF THE SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF BURMA 1974 Printed by Printing and Publishing Corporation Rangoon The Constitution of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma CONTENTS PREAMBLE CHAPTER I THE STATE CHAPTER II BASIC PRINCIPLES CHAPTER III STATE STRUCTURE CHAPTER III STATE STRUCTURE CHAPTER V COUNCIL OF STATE CHAPTER VI COUNCIL OF MINISTERS CHAPTER VII COUNCIL OF PEOPLE'S JUSTICES CHAPTER VIII COUNCIL OF PEOPLE'S ATTORNEYS CHAPTER IX COUNCIL OF PEOPLE'S INSPECTORS CHAPTER X PEOPLE'S COUNCILS CHAPTER XI FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AN DUTIES OF CITIZENS CHAPTER XII ELECTORAL SYSTEM CHAPTER XIII RECALL, RESIGNATION AND REPLACEMENT CHAPTER XIV STATE FLAG, STATE SEAL, NATIONAL ANTHEM, AND STATE CAPITAL CHAPTER XV AMENDMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION CHAPTER XVI GENERAL PROVISIONS CHAPTER XVI GENERAL PROVISIONS We, the people residing in the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma have throughout history lived in harmony and unity sharing joys and sorrows in weal or woe. The people of the land have endeavored with perseverance and undaunted courage, for the attainment of independence, displaying throughout their struggles for national liberation against imperialism an intense patriotism, spirit of mutual help and sacrifice and have aspired to Democracy and Socialism. After attaining independence, the power and influence of the feudalists, landlords, and capitalists had increased and consolidated due to the defects in the old Constitution and the ill-effects of capitalistic parliamentary democracy. The cause of Socialism came under near eclipse. In order to overcome this deterioration and to build Socialism, the Revolutionary Council of the Union of Burma assumed responsibility as a historical mission, adopted the Burmese Way to Socialism, and also formed the Burma Socialist Programme Party. -

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State”

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State” Table of Contents KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 5 1.1. POLITICAL PARTY LANDSCAPE IN RAKHINE STATE............................................................................ 7 1.2. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS .............................................................. 8 1.3. ELECTORAL SYSTEM IN MYANMAR ................................................................................................. 10 2. OBJECTIVE AND SCOPE OF THE STUDY ..................................................................................... 11 1. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 11 1.1. SAMPLING ...................................................................................................................................... 11 1.2. RESEARCH PROCESS ........................................................................................................................ 12 1.3. LIMITATION OF STUDY .................................................................................................................... 12 2. FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................