SOUTHEAST ASIA.Ai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Slash and Burn' Farmers Is Deforesting Mainland Southeast Asia

How Blaming ‘Slash and Burn’ Farmers is Deforesting Mainland Southeast Asia JEFFERSON M. FOX AsiaPacific ISSUES Analysis from the East-West Center SUMMARY For decades, international lenders, agencies, and foundations No. 47 December 2000 as well as national and local governments have spent millions of dollars trying The U.S. Congress established the East-West Center in 1960 to to “modernize” the traditional practices of farmers in many mountainous foster mutual understanding and cooperation among the govern- areas of Southeast Asia—an agenda driven by the belief that their age-old ments and peoples of the Asia Pacific region, including the United shifting cultivation practices (known pejoratively as “slash and burn”) are States. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government deforesting Asia. But a new look at how forests fare under shifting cultivation with additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, (as opposed to under permanent agriculture) clearly demonstrates that efforts corporations, and Asian and Pacific governments. to eliminate the ancient practice have actually contributed to deforestation, The AsiaPacific Issues series 1 contributes to the Center’s role as loss of biodiversity, and reduction in carbon storage. In fact, shifting cultiva- a neutral forum for discussion of issues of regional concern. The tion, rather than being the hobgoblin of tropical forest conservation, may be views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those ecologically appropriate, culturally suitable, and under certain circumstances of the Center. the best means for preserving biodiversity in the region. The real threat to these tropical forests is posed by the steady advance of large-scale permanent and commercial agriculture. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Forest Destruction in Tropical Asia

SPECIAL SECTION: ASIAN BIODIVERSITY CRISES Forest destruction in tropical Asia William F. Laurance Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843–03092, Balboa, Ancón, Panama, USA natural products and lands on which traditional Asian cul- I evaluate trends in forest loss, population size, eco- 8 nomic growth, and corruption within 12 nations that tures rely . contain the large bulk of Asian tropical forests, and Here I evaluate trends in deforestation in the tropical contrast these with trends occurring elsewhere in the Asian region, focusing on closed-canopy forests. I compare tropics. Half of the Asian nations have already experi- surviving forest cover and rates of forest loss among the enced severe (>70%) forest loss, and forest-rich countries, major forested countries in the region, and contrast these such as Indonesia and Malaysia, are experiencing rapid trends with those in other tropical nations in the Americas forest destruction. Both expanding human populations and Equatorial Africa. I also assess the potential influence and industrial drivers of deforestation, such as logging of some demographic and economic variables on Asian and exotic-tree plantations, are important drivers of tropical forests, and highlight some important threats to forest loss. Countries with rapid population growth these forests and their biota. and little surviving forest are also plagued by endemic corruption and low average living standards. Datasets Keywords: Asian tropical forests, biodiversity, defores- tation, logging, population growth. I evaluated changes in forest cover and potentially related demographic and economic variables for 12 countries FOR biologists, the forests of tropical Asia are, by nearly (Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malay- any measure, among the highest of all global conservation sia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Sri priorities. -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency. -

Earth Moves U.S

Earth moves U.S. GOVERNMENTWORLD ™ GEOGRAPHYHISTORY from the Esri GeoInquiries collection for World Geography Target audience – World geography learners Time required – 15 minutes Activity Examine seismic and volcanic activity patterns around the world relative to tectonic plate boundaries, physical features on the earth’s surface, and cities at risk. World Geography C3:D2.Geo.1.6-8. Construct maps to represent and explain the spatial patterns of cultural Standards and environmental characteristics. Learning Outcomes • Locate zones of significant seismic or volcanic activity. • Describe the relationship between zones of high seismic or volcanic activity and tectonic plate boundaries. Map URL: http://esriurl.com/worldGeoInquiry3 Ask Where are global earthquakes located? ʅ Click the link above to launch the map. ʅ Examine the yellow dots on the map that represent earthquakes with a magnitude of 5.7+. ? What patterns do you see on the map? [Answers will vary. Many earthquakes occur on the western coast of North and South America, along the eastern coast of Asia, and along the islands of the Pacific Rim. The pattern follows the Ring of Fire. Earthquakes occur in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.] Acquire Where are the largest earthquakes on Earth? ʅ With the Details button depressed, click the button, Show Contents. ʅ Click the Earthquakes Magnitude 5.7+ layer name, and then click the Show Table button. – Each record in this table represents one point on the map. ʅ Click the Magnitude column heading (field) and choose Sort Descending. ʅ Highlight the first 20 records (highest magnitude earthquakes). (See the Select Features in a Table ToolTip on the next page for details.) ? Where are the blue highlighted high-magnitude earthquakes located on the map? [Mostly in the Ring of Fire, Southeast Asia, and west coast of South America] Explore Where are the active volcanoes on Earth? ʅ In the top-right corner of the table, click the X to close the table. -

The Hawaiian Islands Case Study Robert F

FEATURE Origin of Horticulture in Southeast Asia and the Dispersal of Domesticated Plants to the Pacific Islands by Polynesian Voyagers: The Hawaiian Islands Case Study Robert F. Bevacqua1 Honolulu Botanical Gardens, 50 North Vineyard Boulevard, Honolulu, HI 96817 In the islands of Southeast Asia, following the valleys of the Euphrates, Tigris, and Nile tuber, and fruit crops, such as taro, yams, the Pleistocene or Ice ages, the ancestors of the rivers—and that the first horticultural crops banana, and breadfruit. Polynesians began voyages of exploration into were figs, dates, grapes, olives, lettuce, on- Chang (1976) speculates that the first hor- the Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1) that resulted in the ions, cucumbers, and melons (Halfacre and ticulturists were fishers and gatherers who settlement of the Hawaiian Islands in A.D. 300 Barden, 1979; Janick, 1979). The Greek, Ro- inhabited estuaries in tropical Southeast Asia. (Bellwood, 1987; Finney, 1979; Irwin, 1992; man, and European civilizations refined plant They lived sedentary lives and had mastered Jennings, 1979; Kirch, 1985). These skilled cultivation until it evolved into the discipline the use of canoes. The surrounding terrestrial mariners were also expert horticulturists, who we recognize as horticulture today (Halfacre environment contained a diverse flora that carried aboard their canoes many domesti- and Barden, 1979; Janick, 1979). enabled the fishers to become intimately fa- cated plants that would have a dramatic impact An opposing view associates the begin- miliar with a wide range of plant resources. on the natural environment of the Hawaiian ning of horticulture with early Chinese civili- The first plants to be domesticated were not Islands and other areas of the world. -

The Fall and Rise Again of Plantations in Tropical Asia: History Repeated?

Land 2014, 3, 574-597; doi:10.3390/land3030574 OPEN ACCESS land ISSN 2073-445X www.mdpi.com/journal/land/ Review The Fall and Rise Again of Plantations in Tropical Asia: History Repeated? Derek Byerlee 3938 Georgetown Ct NW, Washington, DC 20007, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-202-492-2544 Received: 21 January 2014; in revised form: 18 June 2014 / Accepted: 23 June 2014 / Published: 30 June 2014 Abstract: The type of agrarian structure employed to produce tropical commodities affects many dimensions of land use, such as ownership inequality, overlapping land rights and conflicts, and land use changes. I conduct a literature review of historical changes in agrarian structures of commodities grown on the upland frontier of mainland Southeast and South Asia, using a case study approach, of tea, rubber, oil palm and cassava. Although the production of all these commodities was initiated in the colonial period on large plantations, over the course of the 20th century, most transited to smallholder systems. Two groups of factors are posited to explain this evolution. First, economic fundamentals related to processing methods and pioneering costs and risks sometimes favored large-scale plantations. Second, policy biases and development paradigms often strongly favored plantations and discriminated against smallholders in the colonial states, especially provision of cheap land and labor. However, beginning after World War I and accelerating after independence, the factors that propped up plantations changed so that by the end of the 20th century, smallholders overwhelmingly dominated perennial crop exports, except possibly oil palm. Surprisingly, in the 21st century there has been a resurgence of investments in plantation agriculture in the frontier countries of Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, driven by very similar factors to a century ago, especially access to cheap land combined with high commodity prices. -

“Regional Environmental Profile of Asia”

EUROPEAN COMMISSION “R EGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE OF ASIA ” Contract n° 2006/120662 Commission Framework Contract EuropeAid/116548/C/SV Lot No 5 : Studies for Asia Final Report November 2006 This report is financed by the European Commission and is presented by the ATOS ORIGIN BELGIUM – AGRER Consortium for the European Commission. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Commission. A project implemented by This project is funded by ATOS ORIGIN BELGIUM and AGRER The European Union Revised Final Draft Regional Environmental Profile for Asia 2 / 135 Revised Final Draft Regional Environmental Profile for Asia REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE FOR ASIA TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...................................................................................................................................................3 1. SUMMARY.........................................................................................................................................3 1.1 STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT .........................................................................................................3 1.2 ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY , LEGISLATION AND INSTITUTIONS ..........................................................3 1.3 EU AND OTHER DONOR CO -OPERATION WITH THE REGION .............................................................3 1.4 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................3 2. STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................................3 -

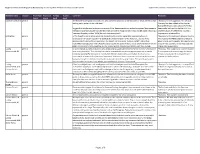

Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Asia and the Pacific Comments External Review First Order Draft - Chapter 3

Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Asia and the Pacific Comments external review first order draft - Chapter 3 Reviewer Name Chapter From Page From Line To Page To Line Comment Response (start) (start) (end) (end) Cameron Colebatch general The documents are good summaries, but what are the implications of the documents? What are the authors Thank you for the suggestion. An Executive seeking policy makers to do with them? Summary has been added to the chapter during the revision, and a separate SPM has Suggest that (at the least) a dot point summary of the 'Recommendations and policy options' be provided at been made. We tried this for the IPCC Asia the beginning of each chapter to make this more prominent. If appropriate, it may also be worth preparing a chapter but got very little extra input for a 'summary for policy makers' (SPM) for each document as well. huge amount of extra effort. LI Qingfeng general 1, The Report in overall is too academia, too detailed in scientific exploration and descriptions. In Thank you for the comment. However, like the consideration of the principal aim “to facilitate the implementation of the National … and the “Inter- IPCC reports, the IPBES output is targeted at governmental” nature of the organization, the Report has to be more “publicly explicit”, rather than governments, not the public. We hope to have “scientifically complicated”. If the Report is to be read by the policy makers, and to draw attentions from the made it more readable, as the FOD stage was public, the content is to be simplified and the volume greatly reduced, one third is more than enough. -

The Role of Rice in Southeast Asia

RESOURCES ESSAYS THE ROLE OF RICE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA By Eric Crystal and Peter Whittlesey Planting Rice with a Smile, Laos, 2000. Photo by Peter Whittlesey his essay will explore the significance of rice in traditional It is thought that rice was first domesticated in northern South- Asian culture. Examples will be drawn primarily from east Asia or southwestern China some 8,000 years ago. Oftentimes T Southeast Asia, a region of the world where the majority of we forget that during the three-million-year term of modern man the population continues to reside in agricultural villages. The pace (homo sapiens), fewer than l2,000 years have been spent in settled of social change has accelerated markedly throughout Asia in recent communities. Only until relatively recent proto-historical times have decades. Urbanization has been increasing and off-farm employment most humans abandoned hunting and gathering in favor of settled opportunities have been expanding. The explosive growth of educa- farming. The agricultural revolution that transformed human soci- tional access, transportation networks, and communication facilities eties from bands of wide-ranging animal hunters and vegetable gath- has transformed the lives of urban dweller and rural farmers alike. erers into settled peasants is thought to have occurred in just a few Despite the evident social, political, and economic changes in Asia in places on earth. Wheat was domesticated in Mesopotamia, corn was recent decades, the centrality of rice to daily life remains largely domesticated in Central America, and rice was domesticated in Asia. unchanged. In most farming villages rice is not only the principal sta- When the ancestors of the present day Polynesian inhabitants of ple, but is the focus of much labor and daily activity. -

Estimating Global Cropland Production from 1961 to 2010

Estimating global cropland production from 1961 to 2010 Pengfei Han1*, Ning Zeng1,2*, Fang Zhao2,3, Xiaohui Lin4 1State Key Laboratory of Numerical Modeling for Atmospheric Sciences and Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China 2Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, and Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA 3Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Potsdam, Brandenburg 14473, Germany 4State Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Boundary Layer Physics and Atmospheric Chemistry, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China Correspondence to: Ning Zeng ([email protected]); Pengfei Han ([email protected]) 1 1 Abstract. Global cropland net primary production (NPP) has tripled over the last fifty 2 years, contributing 17-45 % to the increase of global atmospheric CO2 seasonal 3 amplitude. Although many regional-scale comparisons have been made between 4 statistical data and modelling results, long-term national comparisons across global 5 croplands are scarce due to the lack of detailed spatial-temporal management data. 6 Here, we conducted a simulation study of global cropland NPP from 1961 to 2010 7 using a process-based model called VEGAS and compared the results with Food and 8 Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) statistical data on both 9 continental and country scales. According to the FAO data, the global cropland NPP 10 was 1.3, 1.8, 2.2, 2.6, 3.0 and 3.6 PgC yr-1 in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s 11 and 2010s, respectively. -

Evaluating Morphoscopic Trait Frequencies of Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2014 Evaluating Morphoscopic Trait Frequencies of Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders Melody Dawn Ratliff The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ratliff, Melody Dawn, "Evaluating Morphoscopic Trait Frequencies of Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders" (2014). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4275. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4275 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUTATING MORPHOSCOPIC TRAIT FREQUENCIES OF SOUTHEAST ASIANS AND PACIFIC ISLANDERS By MELODY DAWN RATLIFF Bachelor of Arts, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 2012 Master’s Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2014 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Randall R. Skelton, Ph.D., Chair Department of Anthropology Ashley H. McKeown, Ph.D., Co-Chair Department of Anthropology Jeffrey M. Good, Ph.D., Co-Chair Division of Biological Sciences Joseph T. Hefner, Ph.D., D-ABFA Co-Chair JPAC-CIL, Hickam AFB, HI COPYRIGHT by Melody Dawn Ratliff 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Ratliff, Melody, M.A., May 2014 Anthropology Evaluating Morphoscopic Trait Frequencies of Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders Chairperson: Randall Skelton, Ph.D.