The Fall and Rise Again of Plantations in Tropical Asia: History Repeated?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Slash and Burn' Farmers Is Deforesting Mainland Southeast Asia

How Blaming ‘Slash and Burn’ Farmers is Deforesting Mainland Southeast Asia JEFFERSON M. FOX AsiaPacific ISSUES Analysis from the East-West Center SUMMARY For decades, international lenders, agencies, and foundations No. 47 December 2000 as well as national and local governments have spent millions of dollars trying The U.S. Congress established the East-West Center in 1960 to to “modernize” the traditional practices of farmers in many mountainous foster mutual understanding and cooperation among the govern- areas of Southeast Asia—an agenda driven by the belief that their age-old ments and peoples of the Asia Pacific region, including the United shifting cultivation practices (known pejoratively as “slash and burn”) are States. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government deforesting Asia. But a new look at how forests fare under shifting cultivation with additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, (as opposed to under permanent agriculture) clearly demonstrates that efforts corporations, and Asian and Pacific governments. to eliminate the ancient practice have actually contributed to deforestation, The AsiaPacific Issues series 1 contributes to the Center’s role as loss of biodiversity, and reduction in carbon storage. In fact, shifting cultiva- a neutral forum for discussion of issues of regional concern. The tion, rather than being the hobgoblin of tropical forest conservation, may be views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those ecologically appropriate, culturally suitable, and under certain circumstances of the Center. the best means for preserving biodiversity in the region. The real threat to these tropical forests is posed by the steady advance of large-scale permanent and commercial agriculture. -

Rural Development for Cambodia Key Issues and Constraints

Rural Development for Cambodia Key Issues and Constraints Cambodia’s economic performance over the past decade has been impressive, and poverty reduction has made significant progress. In the 2000s, the contribution of agriculture and agro-industry to overall economic growth has come largely through the accumulation of factors of production—land and labor—as part of an extensive growth of activity, with productivity modestly improving from very low levels. Despite these generally positive signs, there is justifiable concern about Cambodia’s ability to seize the opportunities presented. The concern is that the existing set of structural and institutional constraints, unless addressed by appropriate interventions and policies, will slow down economic growth and poverty reduction. These constraints include (i) an insecurity in land tenure, which inhibits investment in productive activities; (ii) low productivity in land and human capital; (iii) a business-enabling environment that is not conducive to formalized investment; (iv) underdeveloped rural roads and irrigation infrastructure; (v) a finance sector that is unable to mobilize significant funds for agricultural and rural development; and (vi) the critical need to strengthen public expenditure management to optimize scarce resources for effective delivery of rural services. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its Rural Development developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.8 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 903 million for Cambodia struggling on less than $1.25 a day. -

Forest Destruction in Tropical Asia

SPECIAL SECTION: ASIAN BIODIVERSITY CRISES Forest destruction in tropical Asia William F. Laurance Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843–03092, Balboa, Ancón, Panama, USA natural products and lands on which traditional Asian cul- I evaluate trends in forest loss, population size, eco- 8 nomic growth, and corruption within 12 nations that tures rely . contain the large bulk of Asian tropical forests, and Here I evaluate trends in deforestation in the tropical contrast these with trends occurring elsewhere in the Asian region, focusing on closed-canopy forests. I compare tropics. Half of the Asian nations have already experi- surviving forest cover and rates of forest loss among the enced severe (>70%) forest loss, and forest-rich countries, major forested countries in the region, and contrast these such as Indonesia and Malaysia, are experiencing rapid trends with those in other tropical nations in the Americas forest destruction. Both expanding human populations and Equatorial Africa. I also assess the potential influence and industrial drivers of deforestation, such as logging of some demographic and economic variables on Asian and exotic-tree plantations, are important drivers of tropical forests, and highlight some important threats to forest loss. Countries with rapid population growth these forests and their biota. and little surviving forest are also plagued by endemic corruption and low average living standards. Datasets Keywords: Asian tropical forests, biodiversity, defores- tation, logging, population growth. I evaluated changes in forest cover and potentially related demographic and economic variables for 12 countries FOR biologists, the forests of tropical Asia are, by nearly (Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malay- any measure, among the highest of all global conservation sia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Sri priorities. -

Reinvigorating Cambodian Agriculture: Transforming from Extensive to Intensive Agriculture

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Reinvigorating Cambodian agriculture: Transforming from extensive to intensive agriculture Nith, Kosal and Ly, Singhong Université Lumière Lyon 2, Royal University of Law and Economics 25 November 2018 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/93086/ MPRA Paper No. 93086, posted 08 Apr 2019 12:36 UTC Reinvigorating Cambodian Agriculture: Transforming * from Extensive to Intensive Agriculture Nith Kosal† Ly Singhong‡ December 23, 2018 Abstract In this paper we analysis to identify the factor constraining on Cambodian agriculture in transforming from extensive to intensive agriculture. The objective of this study was to examine the general situation of Cambodian agriculture by comparing with neighboring countries in Southeast Asia from a period of 22 years (1996 – 2018) through cultivate areas, technical using, technologies using, fertilizer using, agricultural infrastructure system, agricultural production cost, agricultural output, agricultural market and climate change. The results show that the Cambodian agriculture sector is still at a level where there is significant need to improve the capacity of farmers, the new technologies use and the prevention of climate change. However, the production cost is still high cost and agricultural output has been in low prices. It also causes for farmers to lose confidence in farming and they will be stop working in the sector. Moreover, we also have other policies to improve agriculture sector in Cambodia. JEL classifications : F13, O13, Q13, Q16, Q18. Keywords: Agricultural Development, Agricultural Policy, Agricultural Technology, Intensive Farming, Farmer Education. * For their useful comments and suggestions, we thanks Dr. Saing Chanhang, Paul Angles, Dr. Sam Vicheat, Phay Thonnimith and the participants at the 5th Annual NBC Macroeconomics Conference: Broadening Sources of Cambodia’s Growth. -

“Regional Environmental Profile of Asia”

EUROPEAN COMMISSION “R EGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE OF ASIA ” Contract n° 2006/120662 Commission Framework Contract EuropeAid/116548/C/SV Lot No 5 : Studies for Asia Final Report November 2006 This report is financed by the European Commission and is presented by the ATOS ORIGIN BELGIUM – AGRER Consortium for the European Commission. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Commission. A project implemented by This project is funded by ATOS ORIGIN BELGIUM and AGRER The European Union Revised Final Draft Regional Environmental Profile for Asia 2 / 135 Revised Final Draft Regional Environmental Profile for Asia REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE FOR ASIA TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...................................................................................................................................................3 1. SUMMARY.........................................................................................................................................3 1.1 STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT .........................................................................................................3 1.2 ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY , LEGISLATION AND INSTITUTIONS ..........................................................3 1.3 EU AND OTHER DONOR CO -OPERATION WITH THE REGION .............................................................3 1.4 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................3 2. STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................................3 -

Dear Readers Welcome to the 30Th Issue of Produce Vegetable Oil

Dear readers Welcome to the 30th issue of produce vegetable oil. The oil is not We continue to feature APANews! This issue includes several only rich in nitrogen, phosphorus and developments in agroforestry interesting articles on recent potassium, but can also be education and training through the developments in agroforestry. We converted into industrial biodiesel. SEANAFE News. Articles in this issue also have several contributions This article is indeed timely as recent of SEANAFE News discuss about presenting findings of agroforestry research efforts are focusing on projects on landscape agroforestry, research. alternative sources of fuel and and marketing of agroforestry tree energy. products. There are also updates on Two articles discuss non-wood forest its Research Fellowship Program and products in this issue. One article Another article presents the results reports from the national networks of features the findings of a research of a study that investigated the SEANAFE’s member countries. that explored various ways of storing physiological processes of rattan seeds to increase its viability. agroforestry systems in India. The There are also information on The article also presents a study focused on photosynthesis and upcoming international conferences comprehensive overview of rattan other related growth parameters in agroforestry which you may be seed storage and propagation in that affect crop production under interested in attending. Websites Southeast Asia. tree canopies. and new information sources are also featured to help you in your Another article discusses the In agroforestry promotion and various agroforestry activities. potential of integrating Burma development, the impacts of a five- bamboo in various farming systems year grassroots-oriented project on Thank you very much to all the in India. -

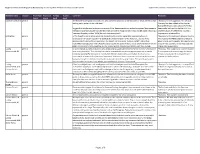

Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Asia and the Pacific Comments External Review First Order Draft - Chapter 3

Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Asia and the Pacific Comments external review first order draft - Chapter 3 Reviewer Name Chapter From Page From Line To Page To Line Comment Response (start) (start) (end) (end) Cameron Colebatch general The documents are good summaries, but what are the implications of the documents? What are the authors Thank you for the suggestion. An Executive seeking policy makers to do with them? Summary has been added to the chapter during the revision, and a separate SPM has Suggest that (at the least) a dot point summary of the 'Recommendations and policy options' be provided at been made. We tried this for the IPCC Asia the beginning of each chapter to make this more prominent. If appropriate, it may also be worth preparing a chapter but got very little extra input for a 'summary for policy makers' (SPM) for each document as well. huge amount of extra effort. LI Qingfeng general 1, The Report in overall is too academia, too detailed in scientific exploration and descriptions. In Thank you for the comment. However, like the consideration of the principal aim “to facilitate the implementation of the National … and the “Inter- IPCC reports, the IPBES output is targeted at governmental” nature of the organization, the Report has to be more “publicly explicit”, rather than governments, not the public. We hope to have “scientifically complicated”. If the Report is to be read by the policy makers, and to draw attentions from the made it more readable, as the FOD stage was public, the content is to be simplified and the volume greatly reduced, one third is more than enough. -

The Role of Rice in Southeast Asia

RESOURCES ESSAYS THE ROLE OF RICE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA By Eric Crystal and Peter Whittlesey Planting Rice with a Smile, Laos, 2000. Photo by Peter Whittlesey his essay will explore the significance of rice in traditional It is thought that rice was first domesticated in northern South- Asian culture. Examples will be drawn primarily from east Asia or southwestern China some 8,000 years ago. Oftentimes T Southeast Asia, a region of the world where the majority of we forget that during the three-million-year term of modern man the population continues to reside in agricultural villages. The pace (homo sapiens), fewer than l2,000 years have been spent in settled of social change has accelerated markedly throughout Asia in recent communities. Only until relatively recent proto-historical times have decades. Urbanization has been increasing and off-farm employment most humans abandoned hunting and gathering in favor of settled opportunities have been expanding. The explosive growth of educa- farming. The agricultural revolution that transformed human soci- tional access, transportation networks, and communication facilities eties from bands of wide-ranging animal hunters and vegetable gath- has transformed the lives of urban dweller and rural farmers alike. erers into settled peasants is thought to have occurred in just a few Despite the evident social, political, and economic changes in Asia in places on earth. Wheat was domesticated in Mesopotamia, corn was recent decades, the centrality of rice to daily life remains largely domesticated in Central America, and rice was domesticated in Asia. unchanged. In most farming villages rice is not only the principal sta- When the ancestors of the present day Polynesian inhabitants of ple, but is the focus of much labor and daily activity. -

Cambodia: Service Provision for Conservation Agriculture

GENDER TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT Appropriate Scale Mechanization Consortium CAMBODIA: SERVICE PROVISION FOR CONSERVATION AGRICULTURE Maria Jones1, Vira Leng2, Socheath Ong3, Makara Mean3 August 2019 1University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, 2Department of Agricultural Land Resources Management, Conservation Agriculture Service Center, 3Royal University of Agriculture, Phnom Penh The USAID funded Appropriate Scale Mechanization Consortium led by the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign develops and promotes appropriate agricultural mechanization technologies for smallholder farmers in Cambodia, Bangladesh, Burkina Faso and Ethiopia. ASMC’s ‘eco-system of innovation’ approach includes the development of local Innovation Hubs comprised of relevant stakeholders to promote and enhance suitable, sustainable, and scalable mechanization. In Cambodia, Innovation Hub leaders and key implementers are Faculty of Agricultural Engineering at the Royal University of Agriculture, Phnom Penh, The Conservation Agriculture Service Center, Department of Agricultural Engineering at the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and CIRAD. SUMMARY Agricultural technologies can improve economic productivity and reduce time spent on agricultural production, processing, and transporting. Men and women have similar propensities to use technologies. However, women are less likely to have access to them compared to men. Ensuring women have better access to agricultural technology, inputs, and information can help lessen the gender gap in agricultural productivity and increase agricultural output globally by 2.5-4% (FAO 2011). The Appropriate Scale Mechanization Consortium (ASMC) project conducted a Gender Technology Assessment of ASMC Cambodia’s service provision for conservation agriculture. This report identifies gender barriers and enablers to adoption of conservation agriculture, understands intra-household gender norms and women’s roles in household technology adoption. -

Plan of Action for Disaster Risk Reduction in Agriculture 2014-2018

Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King General Directorate of Agriculture Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries Plan of Action for Disaster Risk Reduction in Agriculture 2014-2018 DECEMBER 2013 Kingdom of Cambodia Nation, Religion, King General Directorate of Agriculture Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries Plan of Action for Disaster Risk Reduction in Agriculture 2014-2018 ឯកសារន េះ ត្រូវបា ផលិរន ើង នត្ោមជ ំ ួយហិរញ្ញ វរុថពីអគនាយកដ្ឋា ន ណៈកមមោរសហម អ៍ ឺរបុ សត្ាប់ជ ំ ួយម ុសសធម ៌ ិងកិច្ចគំ家រជ សុីវលិ ិងនត្ោមជ ំ ួយបនច្ចកនេសពីអងគោរនសបៀង ងិ កសិកមម ន សហត្បᾶᾶរិត្បចកំ មុពᾶ។ 殶ល់េសស ៈទងំ ឡាយកុនងអរថបេន េះ ម ិ ត្រូវបា ឆុ្េះបញ្ច ំងពីេសស ៈរបស់ សហម អ៍ ឺរបុ ិង ឬ អងគោរនសបៀង ិងកសិកមមន សហត្បᾶᾶរិន ើយ។ 殶ល់ោរផលិរឯកសារន េះ នដ្ឋយផ្ផនក ឬទងំ មូល សត្ាប់ោរបនងើក ោរយល់ដឹង ោរកសាងផ្ផ ោរ ិង នគលបំណងម ិ ផ្សែងរកត្បាកច្់ ំណូ លនានាត្រូវបា អ ុញ្ញ រ នដ្ឋយត្គ ផ្់ រផដល់ ូវោរេេួលសាគ ល់ត្បភព ពរ័ ា៌ ។ 殶ល់ោរផលិរឯកសារន េះ កុនងនគលបំណងផ្សែងរកត្បាកច្់ ំនណញ ត្រូវបា ហាមឃារ ់ នដ្ឋយម ិ បា សុំោរអ ុញ្ញ រិពីអនកផលិរ។ This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection and with technical assistance of Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Commission and or FAO. Reproduction of any part of this publication for awareness raising, planning, and any other non-profit purpose is authorized without prior permission from the publisher, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. -

Estimating Global Cropland Production from 1961 to 2010

Estimating global cropland production from 1961 to 2010 Pengfei Han1*, Ning Zeng1,2*, Fang Zhao2,3, Xiaohui Lin4 1State Key Laboratory of Numerical Modeling for Atmospheric Sciences and Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China 2Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, and Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA 3Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Potsdam, Brandenburg 14473, Germany 4State Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Boundary Layer Physics and Atmospheric Chemistry, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China Correspondence to: Ning Zeng ([email protected]); Pengfei Han ([email protected]) 1 1 Abstract. Global cropland net primary production (NPP) has tripled over the last fifty 2 years, contributing 17-45 % to the increase of global atmospheric CO2 seasonal 3 amplitude. Although many regional-scale comparisons have been made between 4 statistical data and modelling results, long-term national comparisons across global 5 croplands are scarce due to the lack of detailed spatial-temporal management data. 6 Here, we conducted a simulation study of global cropland NPP from 1961 to 2010 7 using a process-based model called VEGAS and compared the results with Food and 8 Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) statistical data on both 9 continental and country scales. According to the FAO data, the global cropland NPP 10 was 1.3, 1.8, 2.2, 2.6, 3.0 and 3.6 PgC yr-1 in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s 11 and 2010s, respectively. -

For Evaluation of Farming Systems

Development and Field Application of the Farm Assessment Index (FAI) for Evaluation of Farming Systems Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Siva Muthuprakash K M (Roll No. 114350003) Under the guidance of Prof. Om P Damani Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Powai, Mumbai – 400076. April 2018 Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “Development and Field Application of the Farm Assessment Index (FAI) for Evaluation of Farming Systems” submitted by me, for the partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to CTARA, IIT Bombay is a record of the research work carried out by me under the supervision of Prof. Om Damani, IIT Bombay, Mumbai. I further declare that this written submission represents my ideas in my own words and wherever other’s ideas or words have been included, I have adequately cited and referenced the original sources. I affirm that I have adhered to all principles of academic honesty and integrity and have not misrepresented or falsified any idea/data/fact/source to the best of my knowledge. I understand that any violation of the above will cause for disciplinary action by the Institute and can also evoke penal action from the sources which have not been cited properly. Date: Siva Muthuprakash K M ii Acknowledgments My first and foremost gratitude to Prof. Om Damani for his guidance, motivation and continuous support in every aspect during my Ph.D. life. Secondly, I express my sincere thanks to all our collaborators especially the members of ASHA (Alliance for Sustainable and Holistic Agriculture) for their support in conceptualizing the project, facilitating field selection, outcome discussions etc.