Contents 35 123 152 255

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bernard Thomas Volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M

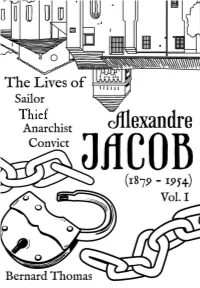

Thief Jacob Alexandre Marius alias Escande Attila George Bonnot Féran Hard to Kill the Robber Bernard Thomas volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno First Published by Tchou Éditions 1970 This edition translated by Paul Sharkey footnotes translated by Laetitia Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno translated by Jean Weir Published in September 2010 by Elephant Editions and Bandit Press Elephant Editions Ardent Press 2013 introduction i the bandits 1 the agitator 37 introduction The impossibility of a perspective that is fully organized in all its details having been widely recognised, rigor and precision have disappeared from the field of human expectations and the need for order and security have moved into the sphere of desire. There, a last fortress built in fret and fury, it has established a foothold for the final battle. Desire is sacred and inviolable. It is what we hold in our hearts, child of our instincts and father of our dreams. We can count on it, it will never betray us. The newest graves, those that we fill in the edges of the cemeteries in the suburbs, are full of this irrational phenomenology. We listen to first principles that once would have made us laugh, assigning stability and pulsion to what we know, after all, is no more than a vague memory of a passing wellbeing, the fleeting wing of a gesture in the fog, the flapping morning wings that rapidly ceded to the needs of repetitiveness, the obsessive and disrespectful repetitiveness of the bureaucrat lurking within us in some dark corner where we select and codify dreams like any other hack in the dissecting rooms of repression. -

Workers of the World: International Journal on Strikes and Social Conflicts, Vol

François Guinchard was born in 1986 and studied social sciences at the Université Paul Valéry (Montpellier, France) and at the Université de Franche-Comté (Besançon, France). His master's dissertation was published by the éditions du Temps perdu under the title L'Association internationale des travailleurs avant la guerre civile d'Espagne (1922-1936). Du syndicalisme révolutionnaire à l'anarcho-syndicalisme [The International Workers’ Association before the Spanish civil war (1922-1936). From revolutionary unionism to anarcho-syndicalism]. (Orthez, France, 2012). He is now preparing a doctoral thesis in contemporary history about the International Workers’ Association between 1945 and 1996, directed by Jean Vigreux, within the Centre George Chevrier of the Université de Bourgogne (Dijon, France). His main research theme is syndicalism but he also took part in a study day on the emigration from Haute-Saône department to Mexico in October 2012. Text originally published in Strikes and Social Conflicts International Association. (2014). Workers of the World: International Journal on Strikes and Social Conflicts, Vol. 1 No. 4. distributed by the ACAT: Asociación Continental Americana de los Trabajadores (American Continental Association of Workers) AIL: Associazione internazionale dei lavoratori (IWA) AIT: Association internationale des travailleurs, Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores (IWA) CFDT: Confédération française démocratique du travail (French Democratic Confederation of Labour) CGT: Confédération générale du travail, Confederación -

Télécharger L'inventaire En

Fonds Sembat-Agutte (XVIIe-1979) Guide (637AP/1-637AP/253, 637AP/AV/254-255, 637AP/256, CP/637AP/257- 258) Par C. Nau-Blin, C. Nougaret et O. Poncet Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2004 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_003563 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2012 par l'entreprise Numen dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) Préface Collaboration et remerciements Claire Blin-Nau, archiviste paléographe Pierre Jugie, conservateur en chef Christine Nougaret, conservateur général Hélène Cavalié, Fanny Lambert, Stéphane Reecht et Aurélie Thomas, élèves stagiaires de l'École nationale des chartes, Guillaume Cornille, stagiaire de l'université Paris I Pascal David, adjoint technique à la Section des archives privées avec la collaboration scientifique de Christian Phéline, éditeur des Cahiers noirs de Marcel Sembat avec la participation de Stéphane Le Flohic, adjoint technique, et Armande Perlot, secrétaire, Section des archives privées/Section ancienne revu, corrigé et complété par Pierre Jugie Nous exprimons notre sincère gratitude à toutes celles et tous ceux qui nous ont apporté leur aide et leurs conseils pour la rédaction de cet instrument de recherche, notamment : Françoise Aujogue, Sandrine Lacombe, Magali Lacousse, -

Anarcho-Syndicalism in the 20Th Century

Anarcho-syndicalism in the 20th Century Vadim Damier Monday, September 28th 2009 Contents Translator’s introduction 4 Preface 7 Part 1: Revolutionary Syndicalism 10 Chapter 1: From the First International to Revolutionary Syndicalism 11 Chapter 2: the Rise of the Revolutionary Syndicalist Movement 17 Chapter 3: Revolutionary Syndicalism and Anarchism 24 Chapter 4: Revolutionary Syndicalism during the First World War 37 Part 2: Anarcho-syndicalism 40 Chapter 5: The Revolutionary Years 41 Chapter 6: From Revolutionary Syndicalism to Anarcho-syndicalism 51 Chapter 7: The World Anarcho-Syndicalist Movement in the 1920’s and 1930’s 64 Chapter 8: Ideological-Theoretical Discussions in Anarcho-syndicalism in the 1920’s-1930’s 68 Part 3: The Spanish Revolution 83 Chapter 9: The Uprising of July 19th 1936 84 2 Chapter 10: Libertarian Communism or Anti-Fascist Unity? 87 Chapter 11: Under the Pressure of Circumstances 94 Chapter 12: The CNT Enters the Government 99 Chapter 13: The CNT in Government - Results and Lessons 108 Chapter 14: Notwithstanding “Circumstances” 111 Chapter 15: The Spanish Revolution and World Anarcho-syndicalism 122 Part 4: Decline and Possible Regeneration 125 Chapter 16: Anarcho-Syndicalism during the Second World War 126 Chapter 17: Anarcho-syndicalism After World War II 130 Chapter 18: Anarcho-syndicalism in contemporary Russia 138 Bibliographic Essay 140 Acronyms 150 3 Translator’s introduction 4 In the first decade of the 21st century many labour unions and labour feder- ations worldwide celebrated their 100th anniversaries. This was an occasion for reflecting on the past century of working class history. Mainstream labour orga- nizations typically understand their own histories as never-ending struggles for better working conditions and a higher standard of living for their members –as the wresting of piecemeal concessions from capitalists and the State. -

Peter Kropotkin and the Social Ecology of Science in Russia, Europe, and England, 1859-1922

THE STRUGGLE FOR COEXISTENCE: PETER KROPOTKIN AND THE SOCIAL ECOLOGY OF SCIENCE IN RUSSIA, EUROPE, AND ENGLAND, 1859-1922 by ERIC M. JOHNSON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) May 2019 © Eric M. Johnson, 2019 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: The Struggle for Coexistence: Peter Kropotkin and the Social Ecology of Science in Russia, Europe, and England, 1859-1922 Submitted by Eric M. Johnson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Examining Committee: Alexei Kojevnikov, History Research Supervisor John Beatty, Philosophy Supervisory Committee Member Mark Leier, History Supervisory Committee Member Piers Hale, History External Examiner Joy Dixon, History University Examiner Lisa Sundstrom, Political Science University Examiner Jaleh Mansoor, Art History Exam Chair ii Abstract This dissertation critically examines the transnational history of evolutionary sociology during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Tracing the efforts of natural philosophers and political theorists, this dissertation explores competing frameworks at the intersection between the natural and human sciences – Social Darwinism at one pole and Socialist Darwinism at the other, the latter best articulated by Peter Alexeyevich Kropotkin’s Darwinian theory of mutual aid. These frameworks were conceptualized within different scientific cultures during a contentious period both in the life sciences as well as the sociopolitical environments of Russia, Europe, and England. This cross- pollination of scientific and sociopolitical discourse contributed to competing frameworks of knowledge construction in both the natural and human sciences. -

Charlotte Wilson, the ''Woman Question'', and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism

IRSH, Page 1 of 34. doi:10.1017/S0020859011000757 r 2011 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Charlotte Wilson, the ‘‘Woman Question’’, and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism S USAN H INELY Department of History, State University of New York at Stony Brook E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: Recent literature on radical movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has re-cast this period as a key stage of contemporary globali- zation, one in which ideological formulations and radical alliances were fluid and did not fall neatly into the categories traditionally assigned by political history. The following analysis of Charlotte Wilson’s anarchist political ideas and activism in late Victorian Britain is an intervention in this new historiography that both supports the thesis of global ideological heterogeneity and supplements it by revealing the challenge to sexual hierarchy that coursed through many of these radical cross- currents. The unexpected alliances Wilson formed in pursuit of her understanding of anarchist socialism underscore the protean nature of radical politics but also show an over-arching consensus that united these disparate groups, a common vision of the socialist future in which the fundamental but oppositional values of self and society would merge. This consensus arguably allowed Wilson’s gendered definition of anarchism to adapt to new terms as she and other socialist women pursued their radical vision as activists in the pre-war women’s movement. INTRODUCTION London in the last decades of the nineteenth century was a global crossroads and political haven for a large number of radical activists and theorists, many of whom were identified with the anarchist school of socialist thought. -

Histoire Des Bourses Du Travail Origine - Institutions - Avenir

Anti.mythes Anti.mythes HISTOIRE DES BOURSES DU TRAVAIL ORIGINE - INSTITUTIONS - AVENIR ----- Ouvrage posthume de Fernand PELLOUTIER Secrétaire général de la Fédération nationale des Bourses du Travail de France et des Colonies Brochure numérique gratuite n°3 d’Anti.mythes: «Histoire des Bourses du Travail». Brochure numérique gratuite n°3 d’Anti.mythes: «Histoire des Bourses du Travail». Page 2 SOMMAIRE: En guise d’avant-propos, par Anti.mythes. 3 «Fernand PELLOUTIER», par Paul DELESALLE, dans Les Temps nouveaux n°48 du 5 23 mars 1901. Notice biographique sur Fernand PELLOUTIER par Victor DAVE. 7 Histoire des Bourses du Travail: Ch. 1: Après la Commune 13 Ch. 2: Les «Partis ouvriers» et les Syndicats 21 Ch. 3: Naissance des Bourses du Travail 24 Ch. 4: Historique des Bourses du Travail 30 Ch. 5: Comment se crée une Bourse du Travail 33 Ch. 6: L’œuvre des Bourses du Travail 36 1- Service de la Mutualité 37 1- Le placement 37 2- Le secours de chômage 38 3- Le viaticum, ou secours aux ouvriers de passage 38 4- L’Offi ce national ouvrier de statistiques et de placement 40 5- Caisses diverses 46 2- Service de l’Enseignement 47 1- Les bibliothèques 47 2- Les Musées du Travail 48 3- Les offi ces de renseignements 49 4- La presse corporative 50 5- L’enseignement 51 3- Le service de la propagande 54 1- Propagande industrielle 55 2- Propagande agraire 55 3- Propagande maritime 58 4- L’action coopérative 61 Ch. 7: Le Comité fédéral des Bourses du Travail 65 Ch. 8: Conjectures sur l’avenir des Bourses du Travail, et conclusion. -

Louise Michel

also published in the rebel lives series: Helen Keller, edited by John Davis Haydee Santamaria, edited by Betsy Maclean Albert Einstein, edited by Jim Green Sacco & Vanzetti, edited by John Davis forthcoming in the rebel lives series: Ho Chi Minh, edited by Alexandra Keeble Chris Hani, edited by Thenjiwe Mtintso rebe I lives, a fresh new series of inexpensive, accessible and provoca tive books unearthing the rebel histories of some familiar figures and introducing some lesser-known rebels rebel lives, selections of writings by and about remarkable women and men whose radicalism has been concealed or forgotten. Edited and introduced by activists and researchers around the world, the series presents stirring accounts of race, class and gender rebellion rebel lives does not seek to canonize its subjects as perfect political models, visionaries or martyrs, but to make available the ideas and stories of imperfect revolutionary human beings to a new generation of readers and aspiring rebels louise michel edited by Nic Maclellan l\1Ocean Press reb� Melbourne. New York www.oceanbooks.com.au Cover design by Sean Walsh and Meaghan Barbuto Copyright © 2004 Ocean Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 1-876175-76-1 Library of Congress Control No: 2004100834 First Printed in 2004 Published by Ocean Press Australia: GPO Box 3279, -

Histoire Des Bourses Du Travail : Origine, Institutions, Avenir / Ouvrage Posthume De Fernand Pelloutier

Histoire des Bourses du travail : origine, institutions, avenir / ouvrage posthume de Fernand Pelloutier,... ; préf. par [...] Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France Pelloutier, Fernand. Histoire des Bourses du travail : origine, institutions, avenir / ouvrage posthume de Fernand Pelloutier,... ; préf. par Georges Sorel ; [Notice biographique sur Fernand Pelloutier] par Victor Dave. 1921. 1/ Les contenus accessibles sur le site Gallica sont pour la plupart des reproductions numériques d'oeuvres tombées dans le domaine public provenant des collections de la BnF. Leur réutilisation s'inscrit dans le cadre de la loi n°78-753 du 17 juillet 1978 : - La réutilisation non commerciale de ces contenus est libre et gratuite dans le respect de la législation en vigueur et notamment du maintien de la mention de source. - La réutilisation commerciale de ces contenus est payante et fait l'objet d'une licence. Est entendue par réutilisation commerciale la revente de contenus sous forme de produits élaborés ou de fourniture de service. CLIQUER ICI POUR ACCÉDER AUX TARIFS ET À LA LICENCE 2/ Les contenus de Gallica sont la propriété de la BnF au sens de l'article L.2112-1 du code général de la propriété des personnes publiques. 3/ Quelques contenus sont soumis à un régime de réutilisation particulier. Il s'agit : - des reproductions de documents protégés par un droit d'auteur appartenant à un tiers. Ces documents ne peuvent être réutilisés, sauf dans le cadre de la copie privée, sans l'autorisation préalable du titulaire des droits. - des reproductions de documents conservés dans les bibliothèques ou autres institutions partenaires. Ceux-ci sont signalés par la mention Source gallica.BnF.fr / Bibliothèque municipale de .. -

Syndicalism and the Influence of Anarchism in France, Italy and Spain

Syndicalism and the Influence of Anarchism in France, Italy and Spain Ralph Darlington, Salford Business School, University of Salford, Salford M5 4WT Phone: 0161-295-5456 Email: [email protected] Abstract Following the Leninist line, a commonly held assumption is that anarchism as a revolutionary movement tends to emerge in politically, socially and economically underdeveloped regions and that its appeal lies with the economically marginalised lumpenproletariat and landless peasantry. This article critically explores this assumption through a comparative analysis of the development and influence of anarchist ideology and organisation in syndicalist movements in France, Spain and Italy and its legacy in discourses surrounding the nature of political authority and accountability. Keywords: syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalism, revolution, unionism, France, Spain, Italy. Introduction Many historians have emphasised the extent to which revolutionary syndicalism was indebted to anarchist philosophy in general and to Bakunin in particular, with some - 1 - even using the term ‘anarcho-syndicalism’ to describe the movement. 1 Certainly within the French, Italian and Spanish syndicalist movements anarchists or so-called ‘anarcho-syndicalists’ were able to gain significant, albeit variable, influence. They were to be responsible in part for the respective movements’ rejection of political parties, elections and parliament in favour of direct action by the unions, as well as their conception of a future society in which, instead of a political -

Ursula Mctaggart

RADICALISM IN AMERICA’S “INDUSTRIAL JUNGLE”: METAPHORS OF THE PRIMITIVE AND THE INDUSTRIAL IN ACTIVIST TEXTS Ursula McTaggart Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Departments of English and American Studies Indiana University June 2008 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Purnima Bose, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ Margo Crawford, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ DeWitt Kilgore ________________________________ Robert Terrill June 18, 2008 ii © 2008 Ursula McTaggart ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A host of people have helped make this dissertation possible. My primary thanks go to Purnima Bose and Margo Crawford, who directed the project, offering constant support and invaluable advice. They have been mentors as well as friends throughout this process. Margo’s enthusiasm and brilliant ideas have buoyed my excitement and confidence about the project, while Purnima’s detailed, pragmatic advice has kept it historically grounded, well documented, and on time! Readers De Witt Kilgore and Robert Terrill also provided insight and commentary that have helped shape the final product. In addition, Purnima Bose’s dissertation group of fellow graduate students Anne Delgado, Chia-Li Kao, Laila Amine, and Karen Dillon has stimulated and refined my thinking along the way. Anne, Chia-Li, Laila, and Karen have devoted their own valuable time to reading drafts and making comments even in the midst of their own dissertation work. This dissertation has also been dependent on the activist work of the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the International Socialists, the Socialist Workers Party, and the diverse field of contemporary anarchists. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term.