Print Media Coverage of the Kenya Defence Forces' Operation 'Linda Nchi'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British-Kenyan Cooperation in the Areas of Defense and Security – 2 a Postcolonial Perspective

1 British-Kenyan Cooperation in the Areas of Defense and Security – 2 A Postcolonial Perspective 3 Łukasz JUREŃCZYK 4 Kazimierz Wielki University, Bydgoszcz, Poland, 5 [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0003-1149-925X 6 7 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37105/sd.104 8 Abstract 9 This paper aims to analyze and evaluate the cooperation between the United Kingdom and Kenya in the areas 10 of defense and security in the second decade of the 21st century. The analysis is conducted in the light of the 11 theory of postcolonialism. The research uses the method of analyzing text sources. This paper begins with an 12 introduction synthetically describing the transition of British-Kenyan relations from colonial to postcolonial 13 and the main methodological assumptions of the paper. Then the theoretical assumptions of postcolonialism 14 are presented. The next three sections include: the circumstances of cooperation in the fields of defense and 15 security; Military cooperation to restore peace in Somalia; and The United Kingdom programs to enhance 16 peace and security in Kenya and East Africa. The paper ends with a conclusion. 17 The main research questions are: Was the defense and security cooperation during the recent decade a con- 18 tinuation of the status quo or was there something different about it? If there was something different, what 19 caused the change? Are there prospects for strengthening the cooperation in the future? 20 Over the past decade, the United Kingdom has strengthened cooperation with Kenya in the areas of defense 21 and security. The actions of the British were aimed at strengthening Kenya's military potential and its ability 22 to influence the international environment. -

Community Perceptions of Violent Extremism in Kenya

COMMUNITY PERCEPTIONS OF VIOLENT EXTREMISM IN KENYA Occasional Paper 21 JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION IN AFRICA COMMUNITY PERCEPTIONS OF VIOLENT EXTREMISM IN KENYA Charles Villa-Vicencio, Stephen Buchanan-Clarke and Alex Humphrey This research was a collaboration between Georgetown University in Washington DC and the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) in Cape Town, in consultation with the Life & Peace Institute (LPI). Published by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation in consultation with the Life & Peace Institute. 105 Hatfield Street Gardens, 8001 Cape Town, South Africa www.ijr.org.za © Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, 2016 First published 2016 All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-928332-13-8 Designed and typeset by COMPRESS.dsl Disclaimer Respondent views captured in this report do not necessarily reflect those held by Georgetown University, the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, or the Life & Peace Institute. Further, it was beyond the scope of this study to investigate specific allegations made by respondents against either state or non-state entities. While efforts were made to capture the testimonies of interview subjects in their first language, inaccuracies may still have been inadvertently captured in the process of translation and transcription. ii Preface The eyes of the world are on the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and the enduring Al-Qaeda-and Taliban-related conflicts in Europe, the Middle East, Afghanistan and Pakistan, with insufficient concern on the growing manifestation of extremism and terrorist attacks in Africa. This report is the culmination of a three-month pilot study which took place in Kenya between June and August 2016. -

Kenya Decision Against Al-Shabaab in Somalia

KENYA DECISION AGAINST AL-SHABAAB IN SOMALIA Lt Col A.M. Gitonga JCSP 42 PCEMI 42 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs do not represent Department of National Defence or et ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used Ministère de la Défense nationale ou des Forces without written permission. canadiennes. Ce papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2016. le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2016. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 42 – PCEMI 42 2015 – 2016 EXERCISE SOLO FLIGHT – EXERCICE SOLO FLIGHT KENYA DECISION AGAINST AL-SHABAAB IN SOMALIA Lt Col A.M. Gitonga “This paper was written by a student “La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is a exigences du cours. L'étude est un scholastic document, and thus contains document qui se rapporte au cours et facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. It does not convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas necessarily reflect the policy or the nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion opinion of any agency, including the d'un organisme quelconque, y compris le Government of Canada and the gouvernement du Canada et le ministère Canadian Department of National de la Défense nationale du Canada. -

Kenya: an African Oil Upstart in Transition

October 2014 Kenya: An African oil upstart in transition OIES PAPER: WPM 53 Luke Patey Danish Institute for International Studies & Research Associate, OIES The contents of this paper are the authors’ sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2014 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78467-011-5 October 2014 - Kenya: An African oil upstart in transition i Acknowledgements I would like to thank Adrian Browne, Bassam Fattouh, Celeste Hicks, Martin Marani, and Mikkel Funder for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of the paper. I alone remain responsible for any errors or shortcomings. October 2014 - Kenya: An African oil upstart in transition ii Executive Summary In late March 2012, Kenya entered the East African oil scene with a surprising splash. After decades of unsuccessful on-and-off exploration by international oil companies, Tullow Oil, a UK-based firm, discovered oil in Kenya’s north-west Turkana County. This paper analyses the opportunities and risks facing Kenya’s oil industry and its role as a regional oil transport hub. It provides a snapshot of Kenya’s economic, political, and security environment, offers a comprehensive overview of the development of Kenya’s oil industry and possibilities for regional oil infrastructure cooperation with neighbouring countries in East Africa, and considers the potential political, social, and security risks facing the oil industry and regional infrastructure plans. -

Peace Builders News

PEACE BUILDERS NEWS A QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF THE INTERNATIONAL PEACE SUPPORT TRAINING CENTRE VOLUME 10, ISSUE 3 (01 JULY - 30 SEPTEMBER 2017) Working towards a Secure Peace Support Operations Environment in the Eastern Africa Region IN THIS ISSUE: • Message from the Director • Staff Induction Seminar 2017 • Nexus Between Maritime and Human Security on Development • Ceding Ground: The Forgotten Host in Refugee Crisis • Refugees in Kenya: Burgen, Threat or Asset? • Training on Protection of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) Disaster Communication and Early Warning in Countering Violent Extremism • Deploying The Best: Enhancing Effectiveness of AU/UN Peacekeepers • Hostile Environment Awareness (HEAT) • One on One with Lisa Hu • IPSTC Third Quarter Course Calendar 2017. VOLUME 10, ISSUE 2 | 01 April - 30 JUNE 2017 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 2 | 01 April - 30 JUNE 2017 1 Table of Contents Message from the Director..............................................2 Staff Induction Seminar 2017...….........……....................4 The Nexus Between Maritime and Human Security on Development…………....................5 Ceding Ground: The Forgotten Host in Refugee Crisis........................................................7 Refugees in Kenya: Burden, Threat or Asset?................8 Working towards a Secure Peace Support Operations Disaster Communication and Early Warning Environment in the Eastern in Countering Violent Extremism...................................11 Africa Region Training on Protection of Refugees and The centre embarked on -

Vanishing Herds Cattle Rustling in East Africa and the Horn

This project is funded by the European Union Issue 10 | December 2019 Vanishing herds Cattle rustling in East Africa and the Horn Deo Gumba, Nelson Alusala and Andrew Kimani Summary Cattle rustling, a term widely accepted to mean livestock theft, has become a widespread and sometimes lethal practice in East Africa and the Horn of Africa regions. Once a traditional practice among nomadic communities, it has now become commercialised by criminal networks that often span communal and international borders and involve a wide range of perpetrators. This paper explores reasons why the problem persists despite national and regional efforts to stem it and suggests some practical ways of managing it. Recommendations • Governments in the region need to re-examine their response to the age-old challenge of cattle rustling, which undermines human security and development. • Most interventions by governments have focused on disarming pastoral communities and promoting peace initiatives although they may not offer a sustainable solution to the problem. • The design and implementation of policies should be guided by informed research rather than by politics. This will ensure that programmes take into consideration the expectations and aspirations of target communities. • Countries in East Africa and the Horn should enhance the existing common objective of a regional response to the transnational nature of cattle rustling by strengthening the existing legislative framework and security cooperation among states in the region. RESEARCH PAPER Background weapons (SALW), should be considered a form of transnational organised crime. Section seven proposes Cattle rustling in East Africa and the Horn was, in a regional approach to the threat, while section seven the past, predominantly practised by pastoral and details an operational framework or roadmap for nomadic communities for two main purposes. -

Kenyatta University School of Humanities and Social

KENYATTA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY EVALUATION OF THE EFFECTS OF KENYA DEFENCE FORCES DEPLOYMENT ON PSYCHOSOCIAL WELL-BEING OF THEIR FAMILIES IN NAIROBI COUNTY MOSES SILALI MAUKA, B.A C50/CTY/22840/2011 A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (COUNSELING PSYCHOLOGY) OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY MAY 2019 DECLARATION This project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university or for any other award. Date Moses Silali Mauka, B.A C50/CTY/PT/22840/2011 This project has been submitted for review with my approval as University supervisor Date Dr. Merecia Ann Sirera Department of Security and Correction Science Kenyatta University ii DEDICATION I dedicate this research project to my wife- Margaret Nambuye Mauka without whose strength and determination to see me through course work this would not have been possible. I also dedicate it to my children Brian, Rebecca, Sarah, and Esther for their moral support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My deepest appreciation and thanks go to my supervisor, Dr. Ann Merecia Ann Sirera for her invaluable guidance and encouragement throughout my period of study, all my lecturers and staff of the Kenyatta University especially the Department of Psychology. I also wish to express my gratitude to the staff at Moi Airbase, Langata Barracks, and Department of Defense that spared their invaluable time to provide the information required for the successful completion of this study. Above all, I’m grateful to the Most High God who has brought me thus far, and His grace has seen me through. -

Inside Kenya's War on Terror: Breaking the Cycle of Violence in Garissa

Inside Kenya’s war on terror: breaking the cycle of violence in Garissa Christopher Wakube, Thomas Nyagah, James Mwangi and Larry Attree Inside Kenyas war on terror: The name of Garissa county in Kenya was heard all over the world after al-Shabaab shot breaking the cycle of violence dead 148 people – 142 of them students – at Garissa University College in April 2015. But the in Garissa story of the mounting violence leading up to that horrific attack, of how and why it happened, I. Attacks in Garissa: towards and of how local communities, leaders and the government came together in the aftermath the precipice to improve the security situation, is less well known. II. Marginalisation and division But when you ask around, it quickly becomes clear that Garissa is a place where divisions and in Garissa dangers persist – connected to its historic marginalisation, local and national political rivalries III. “This is about all of us” – in Kenya, and the ebb and flow of conflict in neighbouring Somalia. Since the attack, the local perceptions of violence security situation has improved in Garissa county, yet this may offer no more than a short IV. Rebuilding trust and unity window for action to solve the challenges and divisions that matter to local people – before other forces and agendas reassert their grip. V. CVE job done – or a peacebuilding moment to grasp? This article by Saferworld tells Garissa’s story as we heard it from people living there. Because Garissa stepped back from the brink of terror-induced polarisation and division, it is in some Read more Saferworld analysis ways a positive story with global policy implications. -

Mission Readiness Mandate the Mandate of the Ministry of Defence Is Derived from Article 241:1 (A), (B) and (C) of the Constitution of the Kenya Defence Forces Act No

KENYA DEFENCE FORCES Majeshi YetuYetu VOLUME 17, 2020 Back to School 2021 New Dawn for Security Telecommunication Services Things to look out for in 2021; - Ulinzi Sports Complex - Space Science Advancement Mission Readiness Mandate The Mandate of the Ministry of Defence is derived from Article 241:1 (a), (b) and (c) of the Constitution of the Kenya Defence Forces Act No. 25 of 2012. Vision A premier, credible and mission capable force deeply rooted in professionalism. Mission To defend and protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic, assist and cooperate with other authorities in situations of emergency or disaster and restore peace in any part of Kenya affected by unrest or instability as assigned. Commitment The Ministry of Defence is committed to defending the people of the Republic of Kenya and their property against external aggression and also providing support to Civil Authority. Preamble The Ministry of Defence is comprised of the Kenya Army, the Kenya Air Force, the Kenya Navy, the Defence Force Constabulary and the Civilian Staff. Core Values To achieve its Mission and Vision, the Ministry is guided by its core values and beliefs namely: Apolitical: The Defence Forces will steer clear of politics and will remain steadfastly apolitical. The Civil Prerogative: The Defence Forces shall always subordinate itself to democratic Civil Authority and will treat the people of Kenya and its other clients with civility at all times. Loyalty and Commitment: The Defence Forces will uphold its loyalty and commitment to the Commander-in-Chief and the Kenya People of the Republic of Kenya through the chain of command. -

External Interventions in Somalia's Civil War. Security Promotion And

External intervention in Somalia’s civil war Mikael Eriksson (Editor) Eriksson Mikael war civil Somalia’s intervention in External The present study examines external intervention in Somalia’s civil war. The focus is on Ethiopia’s, Kenya’s and Uganda’s military engagement in Somalia. The study also analyses the political and military interests of the intervening parties and how their respective interventions might affect each country’s security posture and outlook. The aim of the study is to contribute to a more refined under- standing of Somalia’s conflict and its implications for the security landscape in the Horn of Africa. The study contains both theoretical chapters and three empirically grounded cases studies. The main finding of the report is that Somalia’s neighbours are gradually entering into a more tense political relationship with the government of Somalia. This development is character- ized by a tension between Somalia’s quest for sovereignty and neighbouring states’ visions of a decentralized Somali state- system capable of maintaining security across the country. External Intervention in Somalia’s civil war Security promotion and national interests? Mikael Eriksson (Editor) FOI-R--3718--SE ISSN1650-1942 www.foi.se November 2013 FOI-R--3718--SE Mikael Eriksson (Editor) External Intervention in Somalia’s civil war Security promotion and national interests? Cover: Scanpix (Photo: TT, CORBIS) 1 FOI-R--3718--SE Titel Extern intervention i Somalias inbördeskrig: Främjande av säkerhet och nationella intressen? Title External intervention in Somalia’s civil war: security promotion and national Interests? Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--3718--SE Månad/Month November Utgivningsår/Year 2013 Antal sidor/Pages 137 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Försvarsdepartementet/Ministry of Defence Projektnr/Project no A11306 Godkänd av/Approved by Maria Lignell Jakobsson Ansvarig avdelning Försvarsanalys/Defence Analysis Detta verk är skyddat enligt lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk. -

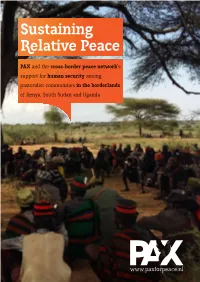

Sustaining Relative Peace

Sustaining Relative Peace PAX and the cross-border peace network’s support for human security among pastoralist communities in the borderlands of Kenya, South Sudan and Uganda www.paxforpeace.nl Colophon By Lotje de Vries and Laura Wunder PAX: Eva Gerritse and Sara Ketelaar July 2017 ISBN: 978-94-92487-16-2 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/08 Photo cover: Inter-community peace dialogue in Kotido, Uganda. Photo credit: Eva Gerritse About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] cross-border peace network. In this report we do not deal with the two programmes separately, but we do want to acknowledge here the important work that our partner the Justice and Peace Preface coordinator of the Diocese of Torit has been doing in the training of Boma councils in Budi, Ikwoto and Torit counties in former Eastern Equatoria State. Secondly, the description in the report of the current conflict dynamics is based on the situation as it was up until June 2016. Sadly, in July 2016, two weeks after the meeting in Naivasha and Kapoeta, violence broke out again in Juba, South Sudan, quickly spreading to the rest of the country and this time also greatly affecting the southern part of the country, the Equatorias. The war in the country and consequent violence, which is still ongoing, had major repercussions for the communities, especially in the western counties of former Eastern Equatoria State. -

Violent Extremism and Clan Dynamics in Kenya

[PEACEW RKS [ VIOLENT EXTREMISM AND CLAN DYNAMICS IN KENYA Ngala Chome ABOUT THE REPORT This report, which is derived from interviews across three Kenyan counties, explores the relationships between resilience and risk to clan violence and to violent extrem- ism in the northeast region of the country. The research was funded by a grant from the United States Agency for International Development through the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), which collaborated with Sahan Africa in conducting the study. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ngala Chome is a former researcher at Sahan Research, where he led a number of countering violent extremism research projects over the past year. Chome has published articles in Critical African Studies, Journal of Eastern Afri- can Studies, and Afrique Contemporine. He is currently a doctoral researcher in African history at Durham University. The author would like to thank Abdulrahman Abdullahi for his excellent research assistance, Andiah Kisia and Lauren Van Metre for helping frame the analysis, the internal reviewers, and two external reviewers for their useful and helpful comments. The author bears responsibility for the final analysis and conclusion. Cover photo: University students join a demonstration condemning the gunmen attack at the Garissa University campus in the Kenyan coastal port city of Mombasa on April 8, 2015. (REUTERS/Joseph Okanga/ IMAGE ID: RTR4WI4K) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Ave., NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No.