A History of Failure Ann Reynolds University of Texas at Austin, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

Eastern State News

Eastern Illinois University The Keep February 1952 2-20-1952 Daily Eastern News: February 20, 1952 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1952_feb Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: February 20, 1952" (1952). February. 3. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1952_feb/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the 1952 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern State News / . "Tell the Truth and Don't Be Afraid" . 17 EASTERN ILLINOIS STATE COLLEGE, CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS WEDNESDAY, FEB. 20, 1952 . .. officer, · . campus leader elections held tomorrow ' Recreation tickets needed nts urged. 'Bowery Ball' to feature -J for. a I I-school voting ly ea rly faculty, stud'?nt f Joor show Warbler sponsors leader election test by Hilah Cherry aft NAMES OF 65 students will appear on the ballot in the election ELIGIBLE to talce IWO FLOOR shows as well as dancing make up the entertainment of class officers consis1ing of the President, Vice President .• elective Service col for the "Bowery Ball," which will be held in the Old Aud, S and· Secretary-Treasurer of all classes in Old Main tomorrow. The tion test should file February 29. election will be held in the south room adjoining president Buz at once, Selective Ser The "Bucket Sisters," Dean Long and Joyce Reynolds as "the zard's office. ieadquarters advis- fat man," and songstress Hilah Cherry are a few of the veteran en A Student Council committee will be in charge of the polls. -

The File on Robert Siodmak in Hollywood: 1941-1951

The File on Robert Siodmak in Hollywood: 1941-1951 by J. Greco ISBN: 1-58112-081-8 DISSERTATION.COM 1999 Copyright © 1999 Joseph Greco All rights reserved. ISBN: 1-58112-081-8 Dissertation.com USA • 1999 www.dissertation.com/library/1120818a.htm TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION PRONOUNCED SEE-ODD-MACK ______________________ 4 CHAPTER ONE GETTING YOUR OWN WAY IN HOLLYWOOD __________ 7 CHAPTER TWO I NEVER PROMISE THEM A GOOD PICTURE ...ONLY A BETTER ONE THAN THEY EXPECTED ______ 25 CHRISTMAS HOLIDAY _____________________________ 25 THE SUSPECT _____________________________________ 49 THE STRANGE AFFAIR OF UNCLE HARRY ___________ 59 THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE ___________________________ 74 THE KILLERS _____________________________________ 86 CRY OF THE CITY_________________________________ 100 CRISS CROSS _____________________________________ 116 THE FILE ON THELMA JORDON ___________________ 132 CHAPTER THREE HOLLYWOOD? A SORT OF ANARCHY _______________ 162 AFTERWORD THE FILE ON ROBERT SIODMAK___________________ 179 THE COMPLETE ROBERT SIODMAK FILMOGRAPHY_ 185 BIBLIOGRAPHY __________________________________ 214 iii INTRODUCTION PRONOUNCED SEE-ODD-MACK Making a film is a matter of cooperation. If you look at the final credits, which nobody reads except for insiders, then you are surprised to see how many colleagues you had who took care of all the details. Everyone says, ‘I made the film’ and doesn’t realize that in the case of a success all branches of film making contributed to it. The director, of course, has everything under control. —Robert Siodmak, November 1971 A book on Robert Siodmak needs an introduction. Although he worked ten years in Hollywood, 1941 to 1951, and made 23 movies, many of them widely popular thrillers and crime melo- dramas, which critics today regard as classics of film noir, his name never became etched into the collective consciousness. -

Patricia Medina Y María Montez. Dos Estrella Coetáneas De Hollywod De

PATRICIA MEDINA Y MARÍA MONTEZ. DOS ESTRELLAS COETÁNE- AS DE HOLLYWOOD DE ASCENDENCIA CANARIA. ANÁLISIS CONTRASTIVO PATRICIA MEDINA AND MARIA MONTEZ. TWO CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD STARS OF CANARY DESCENT. CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS Inodelbia Ramos Pérez* y Pedro Nolasco Leal Cruz** Cómo citar este artículo/Citation: Ramos Pérez, I. y Leal Cruz, P. N. (2017). Patricia Medina y María Montez dos estrellas coetáneas de Hollywood de ascendencia canaria. Análisis contrastivo. XXII Coloquio de Historia Canario-Americana (2016), XXII-064. http://coloquioscanariasmerica.casadecolon.com/index.php/aea/article/view/10007 Resumen: Patricia Medina y María Montez son dos estrellas de Hollywood de ascendencia canaria, el padre de la primera nació en Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, el de la segunda en Garafía (La Palma). Las dos artistas tuvieron una vida paralela y carreras exitosas. Ambas se casaron con actores muy conocidos del cine del siglo pasado. Nuestro objetivo es hacer un estudio y contraste de estas dos famosas actrices. Palabras clave: Patricia Medina, María Móntez, cine, Gran Canaria, La Palma, Hollywood, Siglo XX Abstract: Patricia Medina and Maria Montez are two Hollywood stars of Canary descent. The father of the former was born in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and the father of the latter was born in Garafia (La Palma). Both artists had a parallel life and enjoyed successful careers, both stars had well-known husbands in the world of stardom of the twentieth Century. Our aim is to make a study and contrast between them. Keywords: Patricia Medina, Maria Montez, cinema, Gran Canaria, La Palma, Hollywood, XXth Century INTRODUCCIÓN Canarias tiene el orgullo y privilegio de contar con dos artistas de nivel internacional, hijas de padres canarios. -

Marlon Riggs

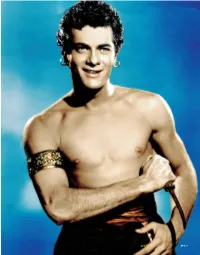

Speaking the Self: Cinema of Transgression Flaming Creatures “At once primitive and sophisticated, hilarious and poignant, spontaneous and studied, frenzied and languid, crude and delicate, avant and nostalgic, gritty and fanciful, fresh and faded, innocent and jaded, high and low, raw and cooked, underground and camp, black and white and white on white, composed and decomposed, richly perverse and gloriously impoverished, Flaming Creatures was something new. Had Jack Smith produced nothing other than this amazing artifice, he would still rank among the great visionaries of American film.” [J. Hoberman] Jack Smith: Flaming Creatures, 1963 • Writer, performance artist, actor. Classic “downtown” underground personality. • Smith endorsed a realm of “secret flix” ranging from B-grade horror movies to Maureen O'Hara Spanish Galleon films, from Busby Berkeley musicals to Dorothy Lamour sarong movies. Singled out Universal Pictures' “Queen of Technicolor,” Maria Montez, star of exotic adventure films such as Arabian Nights (1942), Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1944), and Cobra Woman (1944). • Loose tableau set to scratchy needle-drop music: “polymorphous perverse.” • Banned in New York state, 1964. Vigorous defense by Susan Sontag and others. Outsiders • David Lynch: “John Waters opened up an important space for all of us.” Pink Flamingos • Why has this work come to be celebrated? Midnight Movie shock value or esthetic/cultural importance? • What role does this film play in the lives of its actors? • Film as an esthetic experience vs. film as a liberatory social rallying cry. Compare to punk music. • How does this film address its audience? How might “specific, historical audiences” read this differently? Outsiders “The term camp—normally used as an adjective, even though earliest recorded uses employed it mainly as a verb—refers to the deliberate and sophisticated use of kitsch, mawkish or corny themes and styles in art, clothing or conversation. -

University of Copenhagen Faculty of Humanities

Disincarnation Jack Smith and the character as assemblage Tranholm, Mette Risgård Publication date: 2017 Document version Other version Document license: CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Tranholm, M. R. (2017). Disincarnation: Jack Smith and the character as assemblage. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 26. sep.. 2021 UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN FACULTY OF HUMANITIES PhD Dissertation Mette Tranholm Disincarnation Jack Smith and the character as assemblage Supervisor: Laura Luise Schultz Submitted on: 26 May 2017 Name of department: Department of Arts and Cultural Studies Author(s): Mette Tranholm Title and subtitle: Disincarnation: Jack Smith and the character as assemblage Topic description: The topic of this dissertation is the American performer, photographer, writer, and filmmaker Jack Smith. The purpose of this dissertation is - through Smith - to reach a more nuanced understading of the concept of character in performance theater. Supervisor: Laura Luise Schultz Submitted on: 26 May 2017 2 Table of contents Acknowledgements.............................................................................................................................................................7 Overall aim and research questions.................................................................................................................................9 Disincarnation in Roy Cohn/Jack Smith........................................................................................................................13 -

Edward Said: on Orientalism

MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATIONChallenging media TRANSCRIPT EDWARD SAID: ON ‘ORIENTALISM’ EDWARD SAID On ‘Orientalism’ Executive Producer & Director: Sut Jhally Producer & Editor: Sanjay Talreja Assistant Editor: Jeremy Smith Featuring an interview with Edward Said Professor, Columbia University and author of Orientalism Introduced by Sut Jhally University of Massachusetts-Amherst 2 INTRODUCTION [Montage of entertainment and news images] SUT JHALLY: When future scholars take a look back at the intellectual history of the last quarter of the twentieth century the work of Professor Edward Said of Columbia University will be identified as very important and influential. In particular Said's 1978 book, Orientalism, will be regarded as profoundly significant. Orientalism revolutionized the study of the Middle East and helped to create and shape entire new fields of study such as Post-Colonial theory as well influencing disciplines as diverse as English, History, Anthropology, Political Science and Cultural Studies. The book is now being translated into twenty-six languages and is required reading at many universities and colleges. It is also one of the most controversial scholarly books of the last thirty years sparking intense debate and disagreement. Orientalism tries to answer the question of why, when we think of the Middle East for example, we have a preconceived notion of what kind of people live there, what they believe, how they act. Even though we may never have been there, or indeed even met anyone from there. More generally Orientalism asks, how do we come to understand people, strangers, who look different to us by virtue of the color of their skin? The central argument of Orientalism is that the way that we acquire this knowledge is not innocent or objective but the end result of a process that reflects certain interests. -

Stardom: Industry of Desire 1

STARDOM What makes a star? Why do we have stars? Do we want or need them? Newspapers, magazines, TV chat shows, record sleeves—all display a proliferation of film star images. In the past, we have tended to see stars as cogs in a mass entertainment industry selling desires and ideologies. But since the 1970s, new approaches have explored the active role of the star in producing meanings, pleasures and identities for a diversity of audiences. Stardom brings together some of the best recent writing which represents these new approaches. Drawn from film history, sociology, textual analysis, audience research, psychoanalysis and cultural politics, the essays raise important questions for the politics of representation, the impact of stars on society and the cultural limitations and possibilities of stars. STARDOM Industry of Desire Edited by Christine Gledhill LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 1991 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge a division of Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc. 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1991 editorial matter, Christine Gledhill; individual articles © respective contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Trash Is Truth: Performances of Transgressive Glamour

TRASH IS TRUTH: PERFORMANCES OF TRANSGRESSIVE GLAMOUR JON DAVIES A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Programme in Film and Video, Critical and Historical Studies. York University Toronto, Ontario June 2004 1 2 3 Abstract I will examine several transgressive and transformative performances of glamour in American queer cinema. Primarily, I will look at Mario Montez in the films of Andy Warhol and of Jack Smith (1960s), Divine in the films of John Waters (1970s), and George Kuchar in his own video diaries (1980s). These performances are contradictory, messy, abject, and defiant; they are also profoundly moving to identifying spectators. The power of these performances lies in their harnessing of the experience of shame from queer childhood as a force to articulate deviant queer subjectivities. By forging a radical form of glamour based on a revaluation of trash and low culture, these performances refuse to value authenticity over artifice, beauty over ugliness, truth over trash. This trash glamour is intimately connected to the intense star identification of Hollywood cinematic spectacle that was a survival strategy for queer male children in post-World War Two America. 4 Table of Contents Abstract 4 Table of Contents 5 Introduction 6 1. Theoretical Context 15 2. Super-Fans: Warhol, Smith, Montez 34 3. Divine Shame 62 4. Kuchar’s Queer “Kino-Eye” 97 Conclusion 122 Works Cited 126 Filmography 136 Videography 137 5 Introduction “As Walter Benjamin argued, it is from the ‘flame’ of fictional representations that we warm our ‘shivering lives’” – Peter Brooks I would like to begin with an anecdote that will serve as a point of origin for the connections and resonances among queer childhood, shame, Hollywood fandom, abjection, trash, glamour, and performance that I will develop in this thesis. -

½%Y ‰Žâïý Ä *Ñ ©

120776bk Dietrich2 9/7/04 8:08 PM Page 2 11. Ja, so bin ich 3:05 15. You Do Something to Me 2:57 (Robert Stolz–Walter Reisch) (Cole Porter) Also available from Naxos Nostalgia With Peter Kreuder conducting Wal-Berg’s With Victor Young’s Orchestra; in English Orchestra Decca 23139, mx DLA 1913-A Polydor 524182, mx 6470-1bkp Recorded 19 December 1939, Los Angeles Recorded c. July 1933, Paris 16. Falling in Love Again 2:55 12. Mein blondes Baby 3:14 (Friederich Holländer) (Peter Kreuder–Fritz Rotter) With Victor Young’s Orchestra; in English With Peter Kreuder, piano Decca 23141, mx DLA 1884-C Polydor 524181, mx 6471-4bkp Recorded 11 December 1939, Los Angeles Recorded c. July 1933, Paris 17. The Boys in the Back Room: Parody 13. Allein – in einer grossen Stadt 3:44 1:18 (Franz Wachsmann–Max Kolpe) (Friedrich Holländer–Frank Loesser) With Peter Kreuder conducting Wal-Berg’s With unknown piano; in English Orchestra Private pressing, mx VE 061492-1 8.120557* 8.120558 8.120601* Polydor 524181, mx 6476-3bkp Recorded 1941, Hollywood Recorded c. July 1933, Paris Transfers and Production: David Lennick 14. Wo ist der Mann? 3:08 (Peter Kreuder–Kurt Gerhardt) Digital Noise Reduction: Graham Newton With Peter Kreuder conducting Wal-Berg’s Original recordings from the collections of Orchestra David Lennick and Horst Weggler Polydor 524182, mx 6477 3/4bkp Original monochrome photo from Mary Evans Recorded c. July 1933, Paris Picture Library 8.120613* 8.120630* 8.120722 * Not Available in the U.S. -

EPS 77 ‘Envoi’: a Carlos Fuentes

EPS 77 ‘Envoi’: a Carlos Fuentes. cogen los aspectos más superficiales de rroja se ponían líricos decían cosas como una cultura degradándola con una estéti- “tú, gran señor de los creyentes”, o bien, ca de supermercado. El islam de los peter- “tú, favorita del profeta”; si se ponían vio- panes y las majorettes. Eso sí: entrañable lentos, “tú, hijo de una hiena”, o “tú, bas- como un sueño de infancia y evanescente tardo de un camello”. Se trata de tópicos a como la primera menstruación de las cua- costa de la retórica árabe, o la idea que de tro hermanitas March. ella podía tener un guionista de Holly- Recordad un título de 1949: Bagdad. wood. Mejor aún: un dialoguista de cómics La suprema pelirroja Maureen O’Hara y o un redactor de frases para portadas de el elegante villano Vincent Price obser- pulp magazines. van, desde el desierto, las murallas de la Máximas, adagios, preceptos expresa- ciudad (es decir, un precioso forillo con dos con gran pomposidad por árabes de ra el año 2001. Mien- cúpulas, palmeras y minaretes por do- Wisconsin o Nebraska. Califas, sultanes o tras en los áridos solares de Afganistán quier). tuaregs que ofrecían la seductora apa- el cruzado Bush y sus hordas jugaban al Ella es la princesa Marjane, hija de riencia de Jon –sin hache– Hall, un adonis Egato y al ratón con el islam, la casi ex- un jeque árabe, pero educada en la Ingla- que había hecho de polinesio (!) en Hu- traviada memoria del cinéfilo celebraba terra victoriana. Regresa al hogar sun- racán sobre la isla, junto a Dorothy La- el 50º aniversario de la muerte de la sul- tuosamente vestida a la europea, muy mour, la chica del sarong. -

Angel Sings the Blues: Josef Von Sternberg's the Blue Angel in Context

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 30, núm. 2 (2020) · ISSN: 2014-668X REVIEW ESSAYS . Angel Sings the Blues: Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel in Context ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract This essay reconsiders The Blue Angel (1930) not only in light of its 2001 restoration, but also in light of the following: the careers of Josef von Sternberg, Emil Jannings, and Marlene Dietrich; the 1905 novel by Heinrich Mann from which The Blue Angel was adapted; early sound cinema; and the cultural-historical circumstances out of which the film arose. In The Blue Angel, Dietrich, in particular, found the vehicle by which she could achieve global stardom, and Sternberg—a volatile man of mystery and contradiction, stubbornness and secretiveness, pride and even arrogance—for the first time found a subject on which he could focus his prodigious talent. Keywords: The Blue Angel, Josef von Sternberg, Emil Jannings, Marlene Dietrich, Heinrich Mann, Nazism. Resumen Este ensayo reconsidera El ángel azul (1930) no solo a la luz de su restauración de 2001, sino también a la luz de lo siguiente: las carreras de Josef von Sternberg, Emil Jannings y Marlene Dietrich; la novela de 1905 de Heinrich Mann de la cual se adaptó El ángel azul; cine de sonido temprano; y las circunstancias histórico-culturales de las cuales surgió la película. En El ángel azul, Dietrich, en particular, encontró el vehículo por el cual podía alcanzar el estrellato global, y Sternberg, un hombre volátil de misterio y contradicción, terquedad y secretismo, orgullo e incluso arrogancia, por primera vez encontró un tema en el que podía enfocar su prodigioso talento.