Dietrich and Sternberg : from Cabaret Performance to Feminist Empowerment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 10-6-1982 The aC rroll News- Vol. 67, No. 3 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 67, No. 3" (1982). The Carroll News. 670. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/670 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. OINo. 3 October 6. 1982 tlrbe <!Carroll _jf}etus John Carroll University University Heights, Ohio 44118 Student Union proposes renewal of Stunt Night Will Stunt Night return? This Stunt Night was considered recent. Student Union meeting. tion. laborating data of the past is one of the more popular ques· one of the best sources of class JCU alumni have suggested Student Union President stunt nights, and devising tions pervading the halls of unity, and received significant that Stunt Night be brought Chris Miller says that he is wiU· ground rules which will im· Carroll as of late. yearbook coverage. back, according to senior class ing to lli1ten to any ideas prove future stunt nights. "What is Stunt Night?" you Unfortunately, some of the representative Jim Garvey. students have regarding the Stunt Night was once a main might ask. Actually, it was one material in the skits, which was Presently, the newly-formed return of this much-missed at· event on campus to bring of the bigger events here until intended for the coUege·level Investigative Committee, com· traction. -

Download Booklet

*084Booklet 7/5/06 20:25 Page 1 www.signumrecords.com *084Booklet 7/5/06 20:25 Page 3 also on signumclassics SIMON PRESTON ROYAL ALBERT HALL ORGAN RESTORED 1. Felix Mendelssohn (arr. Best) Overture to the Oratorio ‘St. Paul’, Op 36 [7.44] Robert Schumann Six Fugues on B-A-C-H, Op 60 2. I. Langsam [5.03] 3. II. Lebhaft [5.25] 4. III. Mit sanften Stimmen [3.39] 5. IV. Mäßig, doch nicht zu langsam [4.21] 6. V. Lebhaft [2.43] J.S.Bach Francis Pott Louis Vierne The Art of Fugue SIGCD027 Christus - Passion Symphony SIGCD062 Symphonies pour Orgue SIGCD063 7. VI. Mäßig, nach und nach schneller [6.34] J.S.Bach’s great contrapuntal masterpiece, performed “…an astonishingly original composition, compelling “…sends shivers down the spine ... Filsell has done 8. William Bolcom Free Fantasia on ‘O Zion, Haste’ and ‘How Firm a Foundation’ [7.47] by Colm Carey. in its structural logic and exhilarating in performance. both Vierne and discerning organ-lovers a great 9. George & Ira Gershwin (arr. Cable) The Brothers Gershwin [10.30] All in all, a stupendous achievement” The Times service” The Times 10. Sigfrid Karg-Elert Valse Mignonne, Op 142, No 2 [5.17] 11. Joseph Jongen Sonata Eroïca, Op 94 [15.21] We would like to thank Heather Walker, Deputy Chief Executive and Director of Programming, Richard Knowles, Head of Show Department, Jessica Silvester, Marketing Manager, Alan Pope Total time [74.29] Deputy Show Department Manager (Events) and Caroline Darby, Assistant to the Deputy Chief P 2006 The copyright in this recording is owned by Signum Records Ltd. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

He Museum of Modern Art No

^2. he Museum of Modern Art No. 27 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 245-3200 Cable: Modernart Friday, March 7, I969 PRESS PREVIEW: Wednesday, March 5, I969 1 - k P.M. THE LOST FILM EXHIBIT AT THE MUSEUM PHOTOGRAPHIC GLORY OF VANISHED PAST The Lost Film, an exhibition of stills from early motion pictures that have disappeared or disintegrated, will be officially on view, starting March J, at The Museum of Modern Art, Scenes from 28 films from the twenties by such famous film directors as Erich von Stroheim, Josef von Sternberg, Howard Hawks, Tod Browning, and Frank Borzage are shown, including dramatic stills of Lon Chaney as a hypnotist. Norma Shearer, muffled by an unknown hand, Lewis Stone in the role of a libertine king, and Lionel Barrymore as the Greek manager of a side show. Many of the themes are melodramatic and moralistic with Fay V/ray, of King Kong fame shown as a member of the Salvation Army v;ho reprimands the gangster, Emil Jannings, in the picture "The Street of Sin," made in I928. By contrast "Polly of the Follies" (1922) has Constance Talmadge wearing a derby hat and smoking a cigar. Other black and white scenes come from "The World's Applause" (I923), "Merton of the Movies" (192^), "Confessions of a Queen," (I925), "The Devil's Circus" (I926), "The Show" (1927)^ "Drag Net" (I928), and "The Case of Lena Smith" (I929). They feature many famous actors, among them AdolpheMenjou, Monte Blue, Lillian Gish, George Bancroft, Bessie Love, John Gilbert, and Bebe Daniels. -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

German Cinema As a Vehicle for Teaching Culture, Literature

DOCUMENT7RESUMEA f ED 239 500 FL 014 185 AUTHOR' Duncan, Annelise M. TITLE German Cinema as a Vehicle for Teaching Culture, . Literature and Histoy. 01 PUB DATE Nov 83 . NOTE Pp.; Paper presented at the Annual' Meeting of the. AmeriCan Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (San Franci co, , November 24-26, 1993), PUB TYPE Guides - Cla r om User Guides (For Teachers) (052) Speeches/Conference Papers "(150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Education; *Cultural Education; . *Film Study; *German; Higher Educati-on; History InStruction; Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; *Literature Appreciation; *SeCond Language Instruction; Social HiStory ABSTRACT The use of German film in four instructional; contexts, based on experiences in developinga university course,, is aiScussed. One use is as part ofa German culture course taught in German, emphasizing the role of film as a cultural statement of ,its time, intended to be'either a social criticismor a propaganda tool.t A second use is integration of the film intoa literature course taught in German, employing a series of television' plays acquired from the Embassy of Wkst Germany. Experience with filmas part of an interdisciplinary German/journalism course offers ideas for,a third use: a curriculum, offered in Engl4sh, to explore a hi toric pdriod or film techniques. A fourth use is as an element of p riod course taught either in German or,if interdepartmental, En fish, such as a. course on t'he artistic manifestations of expres (Author/MSE) O 9- * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * 4* * ** * * * * * * * * * *********** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made '* from the original document. -

HERALD Issue See Insert the Only English-Jewish Weekly in Rhode Island and Southeastern Massachusetts

+uuu-H,t-ll-H·H·4H,4H·tr•5-DIGIT 02906 2239 11 /30/93 H bl R. I. JEWISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 130 SESSIONS ST. ,.. t PROVIDEN CE, Rl _____0290b h Rhode I'---- ...... Special Passover --HERALD Issue See Insert The Only English-Jewish Weekly in Rhode Island and Southeastern Massachusetts VOLUME LXXVIV, NUMBER 19 NISAN 10, 5753 / THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 1993 35t PER COPY Knesset Elects Ezer Weizman Celia Zuckerberg, Longtime Herald as Israel's Seventh President Editor, Dies at 74 by Cynthia Mann come under intense criticism by Anne S. Davidson JERUSALEM (JT A) - The for its inability to curb an unre Heuld Editor election last week of Ezer lenting wave of Arab violence. 4 Weizman to be Israel's seventh Al though Weizman was Celia G. Zuckerberg, 74 , a president is being seen here as favored to win, tension was in longtime editor of the RhoJ1• /s la11d Jrwis/i Herald , died March a much-needed victory for the (Continued on Page 6) beleaguered Labor Party. 27 at Miriam Hospital after a Weizman, 68, a national war brief illness. A resident of 506 hero and former defense min Morris Ave., Providence, she ister known for his outspoken Jewish Settler worked for the He rald from the individualism, was elected by late 1950s to the late 1970s, the Knesset on March 24 in a Kills an Arab holding the title of managing t'" 66-53 vote with one absten by Cynthia Mann editor for about 20 years. tion. JERUSA LEM UTA)-AJew But his victory over Ukud ish settler shot and killed a 20- "She was like a one-man Knesset member Dov Shi\ year-old Palestinian whose feet editor. -

Trude Hesterberg She Opened Her Own Cabaret, the Wilde Bühne, in 1921

Hesterberg, Trude Trude Hesterberg she opened her own cabaret, the Wilde Bühne, in 1921. She was also involved in a number of film productions in * 2 May 1892 in Berlin, Deutschland Berlin. She performed in longer guest engagements in Co- † 31 August 1967 in München, Deutschland logne (Metropol-Theater 1913), alongside Massary at the Künstlertheater in Munich and in Switzerland in 1923. Actress, cabaret director, soubrette, diseuse, operetta After the Second World War she worked in Munich as singer, chanson singer theater and film actress, including as Mrs. Peachum in the production of The Threepenny Opera in the Munich „Kleinkunst ist subtile Miniaturarbeit. Da wirkt entwe- chamber plays. der alles oder nichts. Und dennoch ist sie die unberechen- Biography barste und schwerste aller Künste. Die genaue Wirkung eines Chansons ist nicht und unter gar keinen Umstän- Trude Hesterberg was born on 2 May, 1892 in Berlin den vorauszusagen, sie hängt ganz und gar vom Publi- “way out in the sticks” in Oranienburg (Hesterberg. p. 5). kum ab.“ (Hesterberg. Was ich noch sagen wollte…, S. That same year, two events occurred in Berlin that would 113) prove of decisive significance for the life of Getrude Joh- anna Dorothea Helen Hesterberg, as she was christened. „Cabaret is subtle work in miniature. Either everything Firstly, on on 20 August, Max Skladonowsky filmed his works or nothing does. And it is nonetheless the most un- brother Emil doing gymnastics on the roof of Schönhau- predictable and difficult of the arts. The precise effect of ser Allee 148 using a Bioscop camera, his first film record- a chanson is not foreseeable under any circumstances; it ing. -

DCP - Verleihangebot

Mitglied der Fédération D FF – Deutsches Filminstitut & Tel.: +49 (0)611 / 97 000 10 www.dff.film Wiesbadener Volksbank Internationale des Archives Filmmuseum e.V. Fax: +49 (0)611 / 97 000 15 E-Mail: wessolow [email protected] IBAN: D E45510900000000891703 du Film (FIAF) Filmarchiv BIC: WIBADE5W XXX Friedrich-Bergius-Stra ß e 5 65203 Wiesbaden 08/ 2019 DCP - Verleihangebot Die angegebenen Preise verstehen sich pro Vorführung (zzgl. 7 % MwSt. und Versandkosten) inkl. Lizenzgebühren Erläuterung viragiert = ganze Szenen des Films sind monochrom eingefärbt koloriert = einzelne Teile des Bildes sind farblich bearbeitet ohne Angabe = schwarz/weiß restauriert = die Kopie ist technisch bearbeitet rekonstruiert = der Film ist inhaltlich der ursprünglichen Fassung weitgehend angeglichen eUT = mit englischen Untertiteln Kurz-Spielfilm = kürzer als 60 Minuten Deutsches Filminstitut - DIF DCP-Verleihangebot 08/2019 Zwischen Stummfilm Titel / Land / Jahr Regie / Darsteller Titel / Format Preis € Tonfilm Sprache DIE ABENTEUER DES PRINZEN Regie: Lotte Reiniger ACHMED Stummfilm deutsch DCP 100,-- D 1923 / 26 viragiert | restauriert (1999) ALRAUNE Regie: Arthur Maria Rabenalt BRD 1952 Tonfilm Darsteller: Hildegard Knef, Karlheinz Böhm deutsch DCP 200,-- Erich von Stroheim, Harry Meyen ALVORADA - AUFBRUCH IN Regie: Hugo Niebeling BRASILIEN DCP (Dokumentarfilm) Tonfilm deutsch 200,-- Bluray BRD 1961/62 FARBFILM AUF DER REEPERBAHN Regie: Wolfgang Liebeneiner NACHTS UM HALB EINS Tonfilm Darsteller: Hans Albers Fita Benkhoff deutsch DCP 200,-- BRD 1954 Heinz Rühmann Gustav Knuth AUS EINEM DEUTSCHEN Regie: Theodor Kotulla LEBEN Tonfilm Darsteller: Götz George Elisabeth Schwarz deutsch DCP 200,-- BRD 1976/1977 Kai Taschner Hans Korte Regie: Ernst Lubitsch DIE AUSTERNPRINZESSIN deutsch Stummfilm Darsteller: Ossi Oswalda Victor Janson DCP 130,-- Deutschland 1919 eUT mögl. -

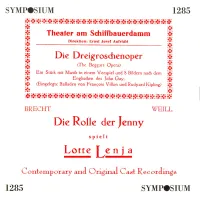

4601553-3Aa246-Booklet-SYMP1285

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1285 MUSIK IN DER WEIMAR REPUBLIK Brecht Die Dreigroschenoper Weill There is an interesting entry for Thursday, 27th September 1928 in Count Harry Kessler’s Diary of a Cosmopolitan, “In the evening saw Brecht’s Dreigroschenoper, music by Weill. A fascinating production, with rudimentary staging in the Piscator style. Weill’s music is catchy and expressive and the players (Harald Paulsen, Rosa Valetti, and so on) are excellent. It is the show of the season, always sold out: ‘You must see it!’”. Perhaps this diary note by an acute observer of the Berlin scene should be framed between two further references. In Before the Deluge, published in 1972, Otto Friedrich (an equally keen observer, he also wrote the introduction to the Kessler volume) commented laconically how “the opening night was a legendary triumph, and of every ten Berliners alive today, at least three claim to have been in the cheering audience”. Kessler’s editor comments that the work made Brecht’s name, and adds that “some of the tunes by Kurt Weill are still sung”. During the last part of the twentieth century, there was a growing interest in ‘rediscovering’ apparently neglected, or forgotten, music. Particular attention has been given to the genre attacked by the Nazis as “Entartete Musik” (degenerate music) of which the compositions of Weill were chosen as prime examples. In January 2000 the BBC celebrated the centenary of Weill’s birth and the fiftieth anniversary of his death by sponsoring a festival at the Barbican focusing on his less familiar works. Popular and media reception was rapturous. -

Appendix 5 Selected Films in English of Operettas by Composers for the German Stage

Appendix 5 Selected Films in English of Operettas by Composers for the German Stage The Merry Widow (Lehár) 1925 Mae Murray & John Gilbert, dir. Erich von Stroheim. Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer. 137 mins. [Silent] 1934 Maurice Chevalier & Jeanette MacDonald, dir. Ernst Lubitsch. MGM. 99 mins. 1952 Lana Turner & Fernando Lamas, dir. Curtis Bernhardt. Turner dubbed by Trudy Erwin. New lyrics by Paul Francis Webster. MGM. 105 mins. The Chocolate Soldier (Straus) 1914 Alice Yorke & Tom Richards, dir. Walter Morton & Hugh Stanislaus Stange. Daisy Feature Film Company [USA]. 50 mins. [Silent] 1941 Nelson Eddy, Risë Stevens & Nigel Bruce, dir. Roy del Ruth. Music adapted by Bronislau Kaper and Herbert Stothart, add. music and lyrics: Gus Kahn and Bronislau Kaper. Screenplay Leonard Lee and Keith Winter based on Ferenc Mulinár’s The Guardsman. MGM. 102 mins. 1955 Risë Stevens & Eddie Albert, dir. Max Liebman. Music adapted by Clay Warnick & Mel Pahl, and arr. Irwin Kostal, add. lyrics: Carolyn Leigh. NBC. 77 mins. The Count of Luxembourg (Lehár) 1926 George Walsh & Helen Lee Worthing, dir. Arthur Gregor. Chadwick Pictures. [Silent] 341 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.14, on 01 Oct 2021 at 07:31:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306 342 Appendix 5 Selected Films in English of Operettas Madame Pompadour (Fall) 1927 Dorothy Gish, Antonio Moreno & Nelson Keys, dir. Herbert Wilcox. British National Films. 70 mins. [Silent] Golden Dawn (Kálmán) 1930 Walter Woolf King & Vivienne Segal, dir. Ray Enright. -

Stardom: Industry of Desire 1

STARDOM What makes a star? Why do we have stars? Do we want or need them? Newspapers, magazines, TV chat shows, record sleeves—all display a proliferation of film star images. In the past, we have tended to see stars as cogs in a mass entertainment industry selling desires and ideologies. But since the 1970s, new approaches have explored the active role of the star in producing meanings, pleasures and identities for a diversity of audiences. Stardom brings together some of the best recent writing which represents these new approaches. Drawn from film history, sociology, textual analysis, audience research, psychoanalysis and cultural politics, the essays raise important questions for the politics of representation, the impact of stars on society and the cultural limitations and possibilities of stars. STARDOM Industry of Desire Edited by Christine Gledhill LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 1991 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge a division of Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc. 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1991 editorial matter, Christine Gledhill; individual articles © respective contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.