Aspects of Trade on the Judaean Coast in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conquest of Arsuf by Baybars: Political and Military Aspects (MSR IX.1, 2005)

REUVEN AMITAI THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM The Conquest of Arsu≠f by Baybars: Political and Military Aspects* A modern-day visitor to Arsu≠f1 cannot help but be struck by the neatly arranged piles of stones from siege machines found at the site. This ordering, of course, represents the labors of contemporary archeologists and their assistants to gather the numerous but scattered stones. Yet, in spite of the recent nature of this "installation," these heaps are clear, if mute, evidence of the great efforts of the Mamluks led by Sultan Baybars (1260–77) to conquer the fortified city from the Franks in 1265. This conquest, as well as its political background and its aftermath, will be the subjects of the present article, which can also be seen as a case-study of Mamluk siege warfare. The immediate backdrop to the Mamluk attack against Arsu≠f was the events of the preceding weeks. At the end of 1264, while Baybars was hunting in the Egyptian countryside, he received reports that the Mongols were heading in force for the Mamluk border fortress of al-B|rah along the Euphrates, today in south- eastern Turkey. The sultan quickly returned to Cairo, and ordered the immediate dispatch of advanced light forces, which were followed by a more organized, but still relatively small, force under the command of the senior amir (officer) Ughan Samm al-Mawt ("the Elixir of Death"), and then by a third corps, together with © Middle East Documentation Center. The University of Chicago. *I would like to thank Prof. Israel Roll of Tel Aviv University, who conducted the excavations at the site, and was most helpful when he showed us the site. -

List of Rivers of Israel

Sl. No River Name Draining Into 1 Nahal Betzet Mediterranean Sea 2 Nahal Kziv Mediterranean Sea 3 Ga'aton River Mediterranean Sea 4 Nahal Na‘aman Mediterranean Sea 5 Kishon River Mediterranean Sea 6 Nahal Taninim Mediterranean Sea 7 Hadera Stream Mediterranean Sea 8 Nahal Alexander Mediterranean Sea 9 Nahal Poleg Mediterranean Sea 10 Yarkon River Mediterranean Sea 11 Ayalon River Mediterranean Sea 12 Nahal Qana Mediterranean Sea 13 Nahal Shillo Mediterranean Sea 14 Nahal Sorek Mediterranean Sea 15 Lakhish River Mediterranean Sea 16 Nahal Shikma Mediterranean Sea 17 HaBesor Stream Mediterranean Sea 18 Nahal Gerar Mediterranean Sea 19 Nahal Be'er Sheva Mediterranean Sea 20 Nahal Havron Mediterranean Sea 21 Jordan River Dead Sea 22 Nahal Harod Dead Sea 23 Nahal Yissakhar Dead Sea 24 Nahal Tavor Dead Sea 25 Yarmouk River Dead Sea 26 Nahal Yavne’el Dead Sea 27 Nahal Arbel Dead Sea 28 Nahal Amud Dead Sea 29 Nahal Korazim Dead Sea 30 Nahal Hazor Dead Sea 31 Nahal Dishon Dead Sea 32 Hasbani River Dead Sea 33 Nahal Ayun Dead Sea 34 Dan River Dead Sea 35 Banias River Dead Sea 36 Nahal HaArava Dead Sea 37 Nahal Neqarot Dead Sea 38 Nahal Ramon Dead Sea 39 Nahal Shivya Dead Sea 40 Nahal Paran Dead Sea 41 Nahal Hiyyon Dead Sea 42 Nahal Zin Dead Sea 43 Tze'elim Stream Dead Sea 44 Nahal Mishmar Dead Sea 45 Nahal Hever Dead Sea 46 Nahal Shahmon Red Sea (Gulf of Aqaba) 47 Nahal Shelomo Red Sea (Gulf of Aqaba) For more information kindly visit : www.downloadexcelfiles.com www.downloadexcelfiles.com. -

Bimt Seminar Handout

Bringing the Bible to LifeSeminar Physical Settings of the Bible Seminar Topics Session I: Introduction - “Physical Settings of the Bible” Session II: “Connecting the Dots” - Geography of Israel Session III: Archaeology & the Bible Session IV: Life & Ministry of Jesus Session V: Jerusalem in the Old Testament Session VI: Jerusalem in the Days of Jesus Session VII: Manners & Customs of the Bible Goals & Objectives • To gain a new and exciting “3-D” perspective of the land of the Bible. • To begin understanding the “playing board” of the Bible. • To pursue the adventure of “connecting the dots” between the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. • To appreciate the context of the stories of the Bible, including the life and ministry of Jesus. • To grow in our walk of faith with the God of redemptive history. 2 Bringing the Bible to Life Seminar About Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours (BIMT) was created 25 years ago (originally called Biblical Israel Tours) out of a passion for leading people to a personalized study tour experience of Israel, the land of the Bible. The ministry expanded in 2016. BIMT is now a support-based evangelical support-based non-profit 501c3 tax-exempt ministry dedicated to helping people “connect the dots” between the context of the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. The two-fold purpose of BIMT is: 1. Leading highly biblical study-discipleship tours to Israel and other lands of the Bible, and 2. Providing “Physical Settings of the Bible” teaching and discipleship training for churches and schools. It is our prayer that BIMT helps people to not only grow in a deeper understanding (e.g. -

Capernaum, the City of Jesus

Capernaum “Then they went into Capernaum, and immediately on the Sabbath He entered the synagogue and taught.” (Mark 1:21) © 2017 David Padfield www.padfield.com Scripture taken from the New King James Version. Copyright 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Capernaum, The City Of Jesus Introduction I. The city of Capernaum was a small fishing village on the northwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee, about two miles west of the Jordan River. A. The Hebrew name for this village is Keœfar NahΩum, which means, “village of Nahum.” B. While this ancient town is not mentioned by name in the Old Testament, it is mentioned sixteen times in the New Testament. C. Matthew refers to Capernaum as our Lord’s “own city” (Matt 9:1), for it became the center of His Galilean ministry. D. This is interesting since He was not born in Capernaum, His parents did not live in there, and He did not grow up there! E. Jesus performed more miracles and preached more sermons in and around Capernaum than at any other place during His entire ministry. F. The residents of this prosperous town were common people who made their living from fishing, agriculture, and trade. G. The road leading to Damascus passed nearby, providing a commercial link with regions to the north and south. H. Capernaum was also a garrison town, housing a detachment of Roman soldiers, under a centurion, along with government officials. II. It was in the vicinity of Capernaum that Jesus chose several of His apostles. -

Innocent Blood — Part One

ONE SESSION SESSION INNOCENT BLOOD — PART ONE Tel Megiddo, where this session was filmed, is located at a strategic mountain pass overlooking the Plain of Jezreel, which made the city of Megiddo one of the most important cities in ancient Israel. The Via Maris, the main trade route between the dominant world pow- ers of the day — Egypt and the Mesopotamian empires of Assyria, Babylon, and Persia — crossed the mountains at Megiddo. So who- ever controlled the city could exert great power over world trade and have significant influence over world culture. In fact, the Via Maris was one source of Solomon’s wealth because God gave him the political might to control the key cities along that trade route — Hazor, Gezer, and of course Megiddo. Some scholars believe that because of Megiddo’s strategic location more battles have been fought in the Jezreel Valley below it than in any other place in the world. But in the context of the Bible, Megiddo repre- sents more than political control, more than economic and cultural influence. It also represents the battle for spiritual control of the minds and hearts of people — the ongoing battle between good and evil. That battle was waged when the people of ancient Israel lived in the land, it continues to this day, and it will culminate in the bat- tle of Har Megiddo, or Armageddon. So let’s take a closer look at the significance of Tel Megiddo. Centuries before the Israelites settled in the Promised Land (from about 2950 – 2350 BC), Megiddo was a prominent “high place” where the p eople of Canaan worshiped their fertility god, Baal, and his supposed mistress, Asherah. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Jaffa's Ancient Inland Harbor: Historical, Cartographic, and Geomorphological Data ������������������������� 89 Aaron A

c hapter 4 Jaffa’s ancient inland harbor: historical,cartographic, and geomorphological data a aron a. burke,1 shelley wachsmann,2 simona avnaim-katav,3 richard k. dunn,4 krister kowalski,5 george a. pierce,6 and martin peilstöcker7 1UniversityofCalifornia,Los Angeles; 2Te xasA&M; 3UniversityofCalifornia, LosAngeles; 4Norwich University; 5Johannes GutenbergUniversity; 6BrighamYoung University; 7Humboldt Universität zu Berlin Thecontext created by recent studies of thegeomorphologyofLevantine harborsand renewedarchaeologicalresearchinthe Late Bronze AgelevelsofTel Yafo (Jaffa) by theJaffa Cultural Heritage Projecthaveled to efforts to identifythe location of apossible inland Bronze andIronAge harbor at Jaffa, Israel.Althoughseveral scholarsduring thetwentieth centuryspeculatedabout theexistenceand location of an ancient inlandharbor, theextent of theproxy data in supportofits identification hasnever been fullyassessed. Nonetheless, a range of historical, cartographic, arthistorical,topographical, andgeomorphologicaldata can be summoned thatpoint to theexistenceofabodyofwater thatlay to theeastofthe settle- ment andmound of ancient Jaffa. This feature is likely avestige of Jaffa’searliestanchorage or harbor andprobablywentout of usebythe startofthe Hellenisticperiod. slongasbiblicalscholars, archaeologists, always directly relatedtoits declineasaport(see historians,and geographershaveconcerned historicaloverviews in Peilstöcker andBurke 2011). athemselves with Jaffa, itsidentityhas revolved Jaffa’seclipse by anotherportisfirstattestedwiththe -

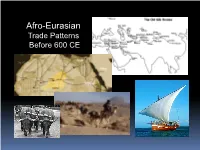

Afro-Eurasian Trade Patterns Before 600 CE Afro-Eurasian Trade Patterns Before 600 CE

Afro-Eurasian Trade Patterns Before 600 CE Afro-Eurasian Trade Patterns before 600 CE What are the four most well known ancient trade routes? • Mediterranean Sea Maritime Trade (c. 1550 BCE – Present) • Trans-Saharan Trade Routes (c. 800 BCE – Present) • Indian Ocean Maritime Trade Route (c. 300 BCE – Present) • Eurasian Silk Road (c. 200 BCE – Present) What other ancient trade routes were important? • Via Maris or “The way of the Sea” (c. 3100 BCE – 1500 CE) • Canal of the Pharaohs (c. 600 BCE – 767 CE) • Incense Trade Route (c. 300 BCE – 200 CE) • Grand Trunk Trade Route (c. 300 BCE – Present) • The Amber Road (c. 200 BCE – 300 CE) Afro-Eurasian Trade Patterns before 600 CE Mediterranean Sea Trade Route • Originated by Phoenician Sea-faring traders (c. 1550 BCE) • Centered on the Phoenician trade centers of Carthage, Cyrene and Tyre • Travel by sea was usually by means of a man-powered vessel with oars Afro-Eurasian Trade Patterns before 600 CE VIA MARIS “Way of the Sea” • Mediterranean Coastal Trade Route originated in the Levant (c. 3100 BCE) KING’S HIGHWAYS • Linking land trade routes connected the regions of Egypt to Mesopotamia (c. 3000 – 1500 BCE) • VIA MARIS and the KING’S HIGHWAYS paved the way for the Phoenicians to create a vast Mediterranean Trade Route by 1550 BCE Afro-Eurasian Trade Patterns before 600 CE TRANS-SAHARAN TRADE ROUTES • The Darb el-Arbain trade route is the earliest of the known Trans-Saharan Caravan Trade Routes (c. 3000 BCE) linking Egypt to the Sudan & Ethiopia • Nomadic Saharan Tribes known as Berber were the first to dominate trade • Expansion of the Trans-Saharan Trade Networks occurred due to the domestication of the Camel (c. -

Lesson 17 - Ist Kings 9 and 10

Lesson 17 - Ist Kings 9 and 10 1ST KINGS Week 17, chapters 9 and 10 We moved into 1st Kings Chapter 9 last week, and the chapter begins sometime after the halfway point of Solomon’s 40 year reign. The Temple is built and in operation, Solomon’s extravagant Palace is completed. King Shlomo’s many building projects throughout his kingdom have elevated his personal fame and Israel’s national status, and monarchs ruling far flung kingdoms are curious and envious of this amazingly wise king and the astounding wealth this relatively small country has amassed almost overnight. Unexpectedly the Lord God appears to Solomon in a dream-vision, just as He had 2 decades earlier at the beginning of Shlomo’s reign. God brings a dual-edged oracle to Solomon; first it is to confirm that He has heard Solomon’s prayers and petitions at the Temple dedication ceremony (now some 13 or more years in the past), and that He has been looking favorably upon them. Second is to issue a reminder that is actually a not-so-veiled threat. Yehoveh reminds Solomon that despite all the adulation and notoriety that is being heaped upon him for his stupendous accomplishments, the future of Solomon’s dynasty and the well-being of the nation of Israel shall always be subject to the Lord’s discretion. The idea is that Solomon should NOT take it that because Israel and its king have become the envy of the world that somehow this is indicative that all is right between Israel and God; the accumulation of wealth and fame is not an earthly indication of righteousness or even harmony with the Lord. -

Nachrbl. Bayer. Ent. 54 (3/4), 2005 101

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nachrichtenblatt der Bayerischen Entomologen Jahr/Year: 2005 Band/Volume: 054 Autor(en)/Author(s): Witt Thomas Josef, Müller Günter C., Kravchenko Vasiliy D., Miller Michael A., Hausmann Axel, Speidel Wolfgang Artikel/Article: A new Olepa species from Israel (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) 101-115 © Münchner Ent. Ges., download www.biologiezentrum.at NachrBl. bayer. Ent. 54 (3/4), 2005 101 A new Olepa species from Israel (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) Thomas J. WITT, Günter C. MÜLLER, Vasiliy D. KRAVCHENKO, Michael A. MILLER, Axel HAUSMANN & Wolfgang SPEIDEL Abstract Olepa schleini sp. nov. is described from the Mediterranean Coastal Plain of Israel and compared with allied species that are all native to the Indian sub-continent. Differential analysis is based on habitus, genital morphology and mtDNA sequence analysis (COI gene). The new species is pro- posed to be cited according to art. 51C of the Code (ICZN), under the name Olepa schleini WITT et al., 2005. Introduction The genus Olepa WATSON, 1980, belongs to the Spilosoma genus-group (Spilarctia genus-group of KÔDA 1988; tribe Spilosomini; subfamily Arctiinae). It was formerly regarded as a monotypical genus represented by the single species Olepa ricini (FABRICIUS, 1775). This view was changed only recently by ORHANT (1986), who revived two taxa from synonymy of ricini to the status of valid species and described five new species from South India and Sri Lanka. Later, Olepa was divided in two species-groups (ORHANT 2000). The ricini group is characterised by a narrow uncus and valvae, which usually are pointed at the tip, whereas the valvae of the ocellifera group have a rounded apex and an additional sub-apical finger-shaped extension, and a broad hood-shaped un- cus. -

Israeli) Star of Hope Agamograph 29 X 31 Cm (11 X 12 In.) Signed Lower Right, Numbered '8/25' Lower Left

1* Yaacov Agam b.1928 (Israeli) Star of Hope agamograph 29 x 31 cm (11 x 12 in.) signed lower right, numbered '8/25' lower left $1,500-1,800 2* Yaacov Agam b.1928 (Israeli) Untitled color silkscreen mounted on panel 57 x 62 cm (22 x 24 in.) signed lower right, numbered 'L/CXLIV' lower left $400-500 3 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Sheep head acrylic on canvas 30 x 30 cm (12 x 12 in.) signed lower left and again on the reverse $450-550 4 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Motherland charcoal on paper 27 x 35 cm (11 x 14 in.) signed lower right $150-220 5 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Valley of sadness pencil on paper 27 x 35 cm (11 x 14 in.) signed lower right $100-150 6* Ruth Schloss 1922-2013 (Israeli) 1 Girl in red dress, 1965 oil on canvas 74 x 50 cm (29 x 20 in.) signed lower right Provenance: Private collection, USA. $3,500-4,000 7 Sami Briss b.1930 (Israeli, French) Doves oil on wood 8 x 10 cm (3 x 4 in.) signed lower center $500-650 8 Nahum Gilboa b.1917 (Israeli) Rural landscape with wooden bridge mixed media on canvasboard 23 x 30 cm (9 x 12 in.) signed lower right, signed and titled on the reverse $1,800-2,200 9 Audrey Bergner b.1927 (Israeli) Flutist oil on canvas 40 x 30 cm (16 x 12 in.) signed lower right, signed and titled on the reverse $4,800-5,500 10 Yohanan Simon 1905-1976 (Israeli) Vegetarian Evolution, 1971 oil on canvas 46 x 54 cm (18 x 21 in.) signed in English lower left, signed in Hebrew and dated lower right, signed, dated and titled on the stretcher $8,000-10,000 11* Yohanan Simon 1905-1976 (Israeli) Wedding, 1969 2 oil on canvas 15 x 23 cm (6 x 9 in.) signed in English lower left and in Hebrew lower right $2,200-2,500 12 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Fallow deer iron cut-out 34 x 30 x 2 cm (13 x 12 x 1 in.) initialled $1,400-1,600 13 Naftali Bezem b. -

Vasemania: Neoclassical Form and Ornament

VOLUME: 4 WINTER, 2004 Vasemania: Neoclassical Form and Ornament: Selections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art at the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture Review by Nancy H. Ramage 1) is a copy of a vase that belonged to Ithaca College Hamilton, painted in Wedgwood’s “encaustic” technique that imitated red-figure with red, An unusual and worthwhile exhibit on the orange, and white painted on top of the “black passion for vases in the 18th century has been basalt” body, as he called it. But here, assembled at the Bard Graduate Center in Wedgwood’s artist has taken all the figures New York City. The show, entitled that encircle the entire vessel on the original, Vasemania: Neoclassical Form and and put them on the front of the pot, just as Ornament: Selections from The Metropolitan they appear in a plate in Hamilton’s first vol- Museum of Art, was curated by a group of ume in the publication of his first collection, graduate students, together with Stefanie sold to the British Museum in 1772. On the Walker at Bard and William Rieder at the Met. original Greek pot, the last two figures on the It aims to set out the different kinds of taste — left and right goût grec, goût étrusque, goût empire — that sides were Fig. 1 Wedgwood Hydria, developed over a period of decades across painted on the Etruria Works, Staffordshire, Britain, France, Italy, Spain, and Germany. back of the ves- ca. 1780. Black basalt with “encaustic” painting. The at the Bard Graduate Center.