"Let No One Wonder at This Image"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T C K a P R (E F C Bc): C P R

ELECTRUM * Vol. 23 (2016): 25–49 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.16.002.5821 www.ejournals.eu/electrum T C K A P R (E F C BC): C P R S1 Christian Körner Universität Bern For Andreas Mehl, with deep gratitude Abstract: At the end of the eighth century, Cyprus came under Assyrian control. For the follow- ing four centuries, the Cypriot monarchs were confronted with the power of the Near Eastern empires. This essay focuses on the relations between the Cypriot kings and the Near Eastern Great Kings from the eighth to the fourth century BC. To understand these relations, two theoretical concepts are applied: the centre-periphery model and the concept of suzerainty. From the central perspective of the Assyrian and Persian empires, Cyprus was situated on the western periphery. Therefore, the local governing traditions were respected by the Assyrian and Persian masters, as long as the petty kings fulfi lled their duties by paying tributes and providing military support when requested to do so. The personal relationship between the Cypriot kings and their masters can best be described as one of suzerainty, where the rulers submitted to a superior ruler, but still retained some autonomy. This relationship was far from being stable, which could lead to manifold mis- understandings between centre and periphery. In this essay, the ways in which suzerainty worked are discussed using several examples of the relations between Cypriot kings and their masters. Key words: Assyria, Persia, Cyprus, Cypriot kings. At the end of the fourth century BC, all the Cypriot kingdoms vanished during the wars of Alexander’s successors Ptolemy and Antigonus, who struggled for control of the is- land. -

Download Download

Nisan / The Levantine Review Volume 4 Number 2 (Winter 2015) Identity and Peoples in History Speculating on Ancient Mediterranean Mysteries Mordechai Nisan* We are familiar with a philo-Semitic disposition characterizing a number of communities, including Phoenicians/Lebanese, Kabyles/Berbers, and Ismailis/Druze, raising the question of a historical foundation binding them all together. The ethnic threads began in the Galilee and Mount Lebanon and later conceivably wound themselves back there in the persona of Al-Muwahiddun [Unitarian] Druze. While DNA testing is a fascinating methodology to verify the similarity or identity of a shared gene pool among ostensibly disparate peoples, we will primarily pursue our inquiry using conventional historical materials, without however—at the end—avoiding the clues offered by modern science. Our thesis seeks to substantiate an intuition, a reading of the contours of tales emanating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Levantine area, to Africa and Egypt, and returning to Israel and Lebanon. The story unfolds with ancient biblical tribes of Israel in the north of their country mixing with, or becoming Lebanese Phoenicians, travelling to North Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya in particular— assimilating among Kabyle Berbers, later fusing with Shi’a Ismailis in the Maghreb, who would then migrate to Egypt, and during the Fatimid period evolve as the Druze. The latter would later flee Egypt and return to Lebanon—the place where their (biological) ancestors had once dwelt. The original core group was composed of Hebrews/Jews, toward whom various communities evince affinity and identity today with the Jewish people and the state of Israel. -

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict?

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict? Maria Natasha Ioannou Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy Discipline of Classics School of Humanities The University of Adelaide December 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................ III Declaration........................................................................................................... IV Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. V Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Overview .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background and Context ................................................................................. 1 3. Thesis Aims ..................................................................................................... 3 4. Thesis Summary .............................................................................................. 4 5. Literature Review ............................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Cyprus Considered .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Cyprus’ Internal Dynamics ........................................................................... 15 1.2 Cyprus, Phoenicia and Egypt ..................................................................... -

The Detrimental Influence of the Canaanite Religion on the Israelite

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za (Accessed: Date). THE DETRIMENTAL INFLUENCE OF THE CANAANITE RELIGION ON THE ISRAELITE RELIGION WITH SPECIFIC REFERENCE TO SACRIFICE by LORRAINE ELIZABETH HALLETT Mini -dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS in BIBLICAL STUDIES in FACULTY OF ARTS at the RAND AFRIKAANS UNIVERSITY SUPERVISOR PROF JH COETZEE NOVEMBER 1995 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the mini -dissertation submitted for the Masters degree to the Rand Afrikaans University, apart from the help recognised, is my own work and has not been formerly submitted to another university for a degree. L E HALLETT (i) ABSTRACT Condemnation (by various biblical writers) of certain practices found amongst the Israelites which led ultimately to the Exile have often been viewed from two opposite views. The believer in the Bible simply accepted the condemnation at face value, and without question, whereas the scholar sought to explain it in terms of extra-biblical knowledge of the history of other civilisations which often threw doubt on the accuracy and veracity of the biblical record. -

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 1

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Lecture 18 Roman Agricultural History Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius View from the Tower of Mercury on the Pompeii city wall looking down the Via di Mercurio toward the forum 1 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Rome 406–88 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 241–27 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 193–211 Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. 2 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Carthage Founded 814 BCE in North Africa Result of Phoenician expansion North African city-state opposite Sicily Mago, 350 BCE, Father of Agriculture Agricultural author wrote a 28 volume work in Punic, A language close to Hebrew. Roman Senate ordered the translation of Mago upon the fall of Carthage despite violent enmity between states. One who has bought land should sell his town house so that he will have no desire to worship the households of the city rather than those of the country; the man who takes great delight in his city residence will have no need of a country estate. Quotation from Columella after Mago Hannibal Capitoline Museums Hall of Hannibal Jacopo Ripanda (attr.) Hannibal in Italy Fresco Beginning of 16th century Roman History 700 BCE Origin from Greek Expansion 640–520 Etruscan civilization 509 Roman Republic 264–261 Punic wars between Carthage and Rome 3 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Roman Culture Debt to Greek, Egyptian, and Babylonian Science and Esthetics Roman expansion due to technology and organization Agricultural Technology Irrigation Grafting Viticulture and Enology Wide knowledge of fruit culture, pulses, wheat Legume rotation Fertility appraisals Cold storage of fruit Specularia—prototype greenhouse using mica Olive oil for cooking and light Ornamental Horticulture Hortus (gardens) Villa urbana Villa rustica, little place in the country Formal gardens of wealthy Garden elements Frescoed walls, statuary, fountains trellises, pergolas, flower boxes, shaded walks, terraces, topiary Getty Museum reconstruction of the Villa of the Papyri. -

Excavations at Carthage Lawrence E

oi.uchicago.edu Excavations at Carthage Lawrence E. Stager The Punic Project operates under an accord between the Tunisian Institut d'Archeologie et d'Art and the American Schools of Oriental Research. It is sponsored by the Harvard Semitic Museum and the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, and funded by a generous grant from the Smithsonian Institution. Further financial support for the 1977 season came from the Uni versity of Missouri-St. Louis and private donors—the "Friends of Carthage." Frank M. Cross, Harvard University, is Principal Inves tigator; Lawrence E. Stager, University of Chicago, is Director. When the Romans conquered Carthage in 146 B.C., two ad joining harbors—a military and a commercial one—served the Carthaginians. Appian gave this brief, but accurate, account of them in his Roman History. 34 oi.uchicago.edu The harbors had communication with each other, and a common entrance from the sea seventy feet wide, which could be closed with iron chains. The first port was for merchant vessels, and here were collected all kinds of ships' tackle. Within the second port was an island, and great quays were set at intervals round both the harbor and the island. These embankments were full of shipyards which had capacity for 220 vessels (Book VIII, 96). Two lagoons, now shallow and silted, proved to be relics of these ancient harbors. On the "island" in the northern lagoon British archeologists have discovered sloping ramps between rows of ashlar sandstone blocks. These undoubtedly formed the founda tions for shipsheds used to drydock the naval fleet. Near the western edge of the southern lagoon our expedition has traced the line of an impressive quay wall also built with ashlar sandstone blocks. -

The Jewish Presence in Cyprus Before Ad 70

SCRIPTA JUDAICA CRACOVIENSIA * Vol. 7 Kraków 2009 Zdzisław J. Kapera THE JEWISH PRESENCE IN CYPRUS BEFORE AD 70 In the time of Sergius Paulus (Acts 13, 7), Cyprus was inhabited by indigenous Cypriots, Greeks (from Greece and Egypt), Phoenicians, some Romans (few in comparison with other groups), and a large community of Jews. What is surprising is the almost total absence of Greek (or Aramaic) synagogue inscriptions, especially since we know from the Acts of the Apostles and other sources that a substantial group of people of Jewish origin was living on the island.1 G. Hill2 and T. B. Mitford3 suggested some decades ago that the first Jews settled in Cyprus in the time of Ptolemy Philadelphus. According to the Talmudic sources, they were very probably obliged to supply wine annually for the services in the Jerusalem Temple.4 However, today we are able to date the first Jewish settlers as early as the fourth century BC. Found in ancient Kition were three Phoenician inscriptions with evidently Jewish names: Haggai, son of Azariah, and Asaphyahu.5 Commercial contacts are later confirmed by finds of Hasmonaean coins in Nea Paphos.6 The first epigraphical proof is provided by a Greek inscription from Kourion of a late Hellenistic date, where a Jew named Onias is mentioned.7 The next attestation of Jews, also of the late Hellenistic or early Roman period, comes from a text dealing with permanent habitation of Jews in Amathus. According to Mitford the text seems to concern “the construction in cedar wood of the doorway of a synagogue” in that city.8 If the Jews built a synagogue, they had a community there. -

Tuna El-Gebel 9

Tuna el-Gebel 9 Weltentstehung und Theologie von Hermopolis Magna I Antike Kosmogonien Beiträge zum internationalen Workshop vom 28.–30. Januar 2016 herausgegeben von Roberto A. Díaz Hernández, Mélanie C. Flossmann-Schütze und Friedhelm Hoffmann Verlag Patrick Brose Tuna el-Gebel - Band 9 Antike Kosmogonien Der Workshop wurde gefördert von: GS DW Graduate School Distant Worlds Der Druck wurde ermöglicht durch: Umschlag: Vorderseite: Foto privat Rückseite: © National Aeronautics and Space Administration (https://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/media/060915/060915_CMB_Timeline600nt.jpg) Tuna el-Gebel - Band 9 Weltentstehung und Theologie von Hermopolis Magna I Antike Kosmogonien Beiträge zum internationalen Workshop vom 28. bis 30. Januar 2016 herausgegeben von Roberto A. Díaz Hernández, Mélanie C. Flossmann-Schütze und Friedhelm Hoffmann Verlag Patrick Brose Vaterstetten Reihe „Tuna el-Gebel“ herausgegeben von Mélanie C. Flossmann-Schütze, Friedhelm Hoffmann, Dieter Kessler, Katrin Schlüter und Alexander Schütze Band 1: Joachim Boessneck (Hg.), Tuna el-Gebel I. Die Tiergalerien, HÄB 24, Hil- desheim 1987. (Gerstenberg Verlag) Band 2: Dieter Kessler, Die Paviankultkammer G-C-C-2, mit einem Beitrag zu den Funden von Hans-Ulrich Onasch, HÄB 43, Hildesheim 1998. (Gersten- berg Verlag) Band 3: Dieter Kessler, Die Oberbauten des Ibiotapheion von Tuna el-Gebel. Die Nachgrabungen der Joint Mission der Universitäten Kairo und München 1989–1996, Tuna el-Gebel 3, Haar 2011. (Verlag Patrick Brose) Band 4: Mélanie C. Flossmann-Schütze / Maren Goecke-Bauer / Friedhelm Hoff- mann / Andreas Hutterer / Katrin Schlüter / Alexander Schütze / Martina Ullmann (Hg.), Kleine Götter – Große Götter. Festschrift für Dieter Kessler zum 65. Geburtstag, Tuna el-Gebel 4, Vaterstetten 2013. (Verlag Patrick Brose) Band 5: Birgit Jordan, Die demotischen Wissenstexte (Recht und Mathematik) des pMattha, 2 Bände, Tuna el-Gebel 5, Vaterstetten 2015. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

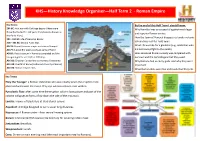

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

On the Rise and Fall of Canaanite Religion at Baalbek: a Tale of Five Toponyms

JBL 128, no. 3 (2009): 507–525 On the Rise and Fall of Canaanite Religion at Baalbek: A Tale of Five Toponyms richard c. steiner [email protected] Revel Graduate School, Yeshiva University, New York, NY 10033 The city of Baalbek, in present-day Lebanon, has been a subject of interest to students of the Bible for more than a millennium. Since the tenth century c.e., many have identified it with Baal-Gad (Josh 11:17) and/or Baalath (1 Kgs 9:18).1 Since the beginning of the eighteenth century, others have connected it, in one way or another, with Bikath-Aven (Amos 1:5). In 1863, these and other suggestions were reviewed by John Hogg in a lengthy treatise.2 The etymology of the toponym, which appears as Bvlbk in classical Syriac and as Bavlabakku in classical Arabic, has been widely discussed since the eighteenth century. Many etymologies have been suggested, most of them unconvincing.3 Part of the problem is that a combination of etymologies is needed, for the name of the place changed over the centuries as its religious significance evolved. In this article, I shall attempt to show that the rise and fall of Canaanite reli- gion at Baalbek from the Bronze Age to the Byzantine period can be traced with the help of five toponyms: (1) Mbk Nhrm (Source of the Two Rivers),4 (2) Nw) t(qb 1 See Richard C. Steiner, “The Byzantine Biblical Commentaries from the Genizah: Rab- banite vs. Karaite,” in Shai le-Sara Japhet (ed. M. Bar-Asher et al.; Jerusalem: Bialik, 2007), *258; and Conrad Iken, Dissertationis philologico-theologicae no. -

Women in Pompeii Author(S): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol

Women in Pompeii Author(s): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 5 (September/October 1979), pp. 34-43 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41726375 . Accessed: 19/03/2014 08:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 170.24.130.117 on Wed, 19 Mar 2014 08:08:22 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Wfomen in Pompeii by Elizabeth Lyding Will year 1979 marks the 1900th anniversary of the fatefulburial of Pompeii, Her- The culaneum and the other sitesengulfed by the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in a.d. 79. It was the most devastatingdisaster in the Mediterranean area since the volcano on Thera erupted one and a half millenniaearlier. The suddenness of the A well-bornPompeian woman drawn from the original wall in theHouse Ariadne PierreGusman volcanic almost froze the bus- painting of by onslaught instantly ( 1862-1941), a Frenchartist and arthistorian. Many tling Roman cityof Pompeii, creating a veritable Pompeianwomen were successful in business, including time capsule. -

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) the Punic Wars

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) The Punic Wars After subjugating the Greek colonies in southern Italy, Rome sought to control western Mediterranean trade. Its chief rival, located across the Mediterranean in northern Africa, was the city-state of Carthage. Originally a Phoenician colony, Carthage had become a powerful commercial empire. Rome defeated Carthage in three Punic (Phoenician) Wars and gained mastery of the western Mediterranean. The First Punic War (264-241 B.C.) Fighting chiefly on the island of Sicily and in the Mediterranean Sea, Rome’s citizen-soldiers eventually defeated Carthage’s mercenaries(hired foreign soldiers). Rome annexed Sicily and then Sardinia and Corsica. Both sides prepared to renew the struggle. Carthage acquired a part of Spain and recruited Spanish troops. Rome consolidated its position in Italy by conquering the Gauls, thereby extending its rule northward from the Po River to the Alps. The Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.) Hannibal, Carthage’s great general, led an army from Spain across the Alps and into Italy. At first he won numerous victories, climaxed by the battle of Cannae. However, he was unable to seize the city of Rome. Gradually the tide of battle turned in favor of Rome. The Romans destroyed a Carthaginian army sent to reinforce Hannibal, then conquered Spain, and finally invaded North Africa. Hannibal withdrew his army from Italy to defend Carthage but, in the Battle of Zama, was at last defeated. Rome annexed Carthage’s Spanish provinces and reduced Carthage to a second-rate power. Hannibal of Carthage Reasons for Rome’s Victory • superior wealth and military power, • the loyalty of most of its allies, and • the rise of capable generals, notably Fabius and Scipio.