We Should Work for Simple, Good, Undecorated Things”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helsinki Echo

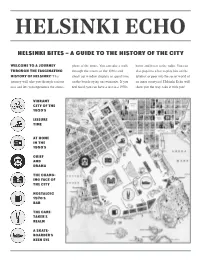

HELSINKI ECHO HELSINKI BITES – A GUIDE TO the HistORY OF the CitY WelcOME TO A JOURneY phere of the times. You can take a walk home and listen to the radio. You can thROUgh the Fascinating through the streets of the 1930s and also pop into a bar to play hits on the histORY OF Helsinki! This check out window displays or spend time jukebox or peer into the secret world of journey will take you through various on the beach trying on swimsuits. If you an inner courtyard. Helsinki Echo will eras and lets you experience the atmos- feel tired, you can have a rest in a 1950s show you the way, take it with you! VibRant CitY OF the 1930'S LeisURE TIME AT HOME in the 1950'S GRieF anD DRAMA The Chang- ing Face OF the CITY NOstalgic 1970'S BAR The CARE- takeR'S RealM A Skate- BOARDER'S KEEN EYE 2 | ALONG THE STREETS Helsinki echO | 3 The CAFÉ BRONDin at Etelä- Wäinö Aaltonen, Rudolf Koivu and having a permanent place to stay since Esplanadi 20 becomes a popular meet- Eino Leino. One of the “Brondinistas” student days, and every member of our ing place among artists in the 1910s. is named Ponkki. “Ponkki was no art- coterie felt it their duty to put him up The regulars include such names as ist. He had no speciality, but he under- when he turned up at your doorstep.”* Jalmari Ruokokoski, Tyko Sallinen, stood everybody. No one recalled him * Vilho Nenonen: Tavattiin Brondalla. SPReaDing like ElantO Shops of the Elanto Cooperative were a familiar sight in Helsinki. -

Tehdään Elementeistä Suomalaisen Betonielementtirakentamisen Historia

Tehdään elementeistä Suomalaisen betonielementtirakentamisen historia SBK-säätiö Tehdään elementeistä Tehdään elementeistä Suomalaisen betonielementtirakentamisen historia Tehdään elementeistä Suomalaisen betonielementtirakentamisen historia SBK-säätiö Kannen kuva: Temppeliaukion kirkko, Helsingin suosituimpia nähtävyyksiä. Kirkon vuosittainen kävijämäärä on noin puoli miljoonaa. Arkkitehdit Timo ja Tuomo Suomalainen. Tehdään elementeistä. Arkkitehti Tuomo Suomalaisen kertomaa: Taivallahden seurakunnan kirkon arkkitehtuurikilpailuun valmistauduttaessa vuonna 1960 neuvoteltiin suunnitelman rakenteista diplomi-insinööri Paavo Simulan kanssa. Katon palkiston rakennustapaa pohdittaessa Simula ehdotti: ”Tehdään elementeistä – Janhunen tekee elementit”. Elementit toimitti vuonna 1968 ins.tsto Esijännitystekniikka Henri Janhunen Ky. Kustantaja: SBK-säätiö Julkaisija: Betonitieto Oy © 2009 kirjoittajat ja SBK-säätiö Teksti: Yki Hytönen ja Matti Seppänen Kuvatoimitus: Petri Janhunen, Kari Laukkanen ja Matti Seppänen Ulkoasu & taitto sekä repro & kuvankäsittely: Peter Sandberg Paino: Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy, Jyväskylä 2009 ISBN 978-952-92-5772-0 5 Sisältö Alkusanat 7 Mitä on ”Sangen vaikeaa Saatteeksi 9 teollinen rakentaminen 46 mutta ei epätoivoista” 94 ”Sandwich” ja ”kirjahylly” 47 BES-tutkimus 96 Kohti täyselementtitaloja 50 1. Sileävalukerho 50 TEOLLISEN Haka etenee ketjuttamalla 54 Huippuvuodet 99 RAKENTAMISEN Kustannussäästöjä tavoitellen 55 Nousukausi 99 NOUSU 11 Sementtiteollisuus tulee mukaan 100 Elementtien BES-rakentaminen käynnistyy 104 -

1E51101eb04baca110111e5b58

世界中から… いままでに42か国から400人近い学生たちがこの凝縮された建築と文化と建設の経験を積むために参加している。 Dipoli Student Building (Reima and Raili Pietilä, 1966) The Main Building (Alvar Aalto, 1965) Servin Mökki (Heikki and Kaj Siren, 1954) New Arts Building 'Väre' (Verstas Architects, 2017) Otaniemi Chapel (Heikki and Kaj Siren, 1957) School of Architecture (Alvar Aalto, 1965) 30 Wood Program projects built from 1994 to 2015 アアルト大学のウッド・プログラムは建築学科のデザイン&ビルドのスタ The Wood Program began at Aalto University in 1994 as a design+build 第二次世界大戦をきっかけにヘルシンキ工科大学(現アアルト大学)はヘ Following World War II, the Helsinki University of Technology (now Aalto ジオ・ゼミとして1994年に始まった。そして2001年には講義と演習旅行、 studio in the Department of Architecture. In 2001 it was expanded into a ルシンキの中心部からオタニエミに移転した。フィンランドの建築家の中 University) moved its facilities from central Helsinki to Otaniemi. Renowned ワークショップ形式の演習を組み合わせた1年間のプログラムとなり、フィ year-long curriculum of lectures, excursions and workshop exercises that でも名高い、アルヴァ・アアルトがオタニエミ・キャンパスのマスタープラ Finnish architect Alvar Aalto designed the campus plan as well as the main ンランドの建築環境に囲まれて木造を学びたいという世界各国からの学生 attracts students from around the world who come to study wood in a Finnish ンに加えて管理棟の建物もデザインして、1965 年に竣工している。 administrative building which opened in 1965. たちを惹きつけるようになったのである。 architectural environment. その数年後にはアアルトの手による建築学科や図書館本館などを含むそ Other buildings including the School of Architecture and the main library were アアルト大学建築学科に設けられたこのプログラムで、学生たちは木造建 Centered in the Department of Architecture at Aalto University, the program の他の建物も完成した。その後もフィンランドの第一線の建築家たちによ completed in subsequent years by -

Paimio Sanatorium

MARIANNA HE IKINHEIMO ALVAR AALTO’S PAIMIO SANATORIUM PAIMIO AALTO’S ALVAR ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: : PAIMIO SANATORIUM ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium TIIVISTELMÄ rkkitehti, kuvataiteen maisteri Marianna Heikinheimon arkkitehtuurin histo- rian alaan kuuluva väitöskirja Architecture and Technology: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio A Sanatorium tarkastelee arkkitehtuurin ja teknologian suhdetta suomalaisen mestariarkkitehdin Alvar Aallon suunnittelemassa Paimion parantolassa (1928–1933). Teosta pidetään Aallon uran käännekohtana ja yhtenä maailmansotien välisen moder- nismin kansainvälisesti keskeisimpänä teoksena. Eurooppalainen arkkitehtuuri koki tuolloin valtavan ideologisen muutoksen pyrkiessään vastaamaan yhä nopeammin teollis- tuvan ja kaupungistuvan yhteiskunnan haasteisiin. Aalto tuli kosketuksiin avantgardisti- arkkitehtien kanssa Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne -järjestön piirissä vuodesta 1929 alkaen. Hän pyrki Paimion parantolassa, siihenastisen uransa haastavim- massa työssä, soveltamaan uutta näkemystään arkkitehtuurista. Työn teoreettisena näkökulmana on ranskalaisen sosiologin Bruno Latourin (1947–) aktiivisesti kehittämä toimijaverkkoteoria, joka korostaa paitsi sosiaalisten, myös materi- aalisten tekijöiden osuutta teknologisten järjestelmien muotoutumisessa. Teorian mukaan sosiaalisten ja materiaalisten toimijoiden välinen suhde ei ole yksisuuntainen, mikä huo- mio avaa kiinnostavia näkökulmia arkkitehtuuritutkimuksen kannalta. Olen ymmärtänyt arkkitehtuurin -

Yolanda Ortega Sanz Universitat De Girona

Yolanda Ortega Sanz Universitat de Girona Yolanda Ortega Sanz is an architect Her research has been published and pre- and associate professor at Polytechnic sented in several conferences as: 1st In- School, Universitat de Girona, Catalonia, ternational Conference on contemporary Spain; where she teaches architectural architects: Jørn Utzon, Sevilla, Spain; 1st design. Ortega was educated at School of Conference on architectural competition, architecture in Barcelona and Arkitekts- Nordic Symposium, KTH, Stockholm, kolen i Aarhus, Denmark. Later on, she Sweden; or Responsibilities and Oppor- received a grant to be a young researcher tunities in Architectural Conservation, at Danmarks Kunstbibliotek, Copenhagen. CSAAR, Amman, Jordan. Currently, she is PhD Candidate in the research group FORM where she develops her thesis entitled “Nordic assembly” focus on Modern Architecture in Nordic countries. Welfare State. Sociological Aesthetics Welfare | Ortega Sanz | 474 WELFARE STATE. SOCIOLOGICAL AESTHETICS Modern architecture and democracy on Nordic countries, Denmark [My theme] concerns itself with the creation of beauty and with the measure of its reverberations in the democratic society. By the word “democracy” […] I speak of the form of life which, without political iden- tification, is slowly spreading over the whole world, establishing itself upon the foundation of increasing industrialization, growing communi- cation and information services, and the broad admission of the masses to higher education and the right to vote. What is the relationship of this form of life to art and architecture today? Walter Gropius1 ERBE DER MODERNE DAS In 1954, thirty-five years after founding the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius travelled around the world, revising his ideas about a democratic environment for the twentieth-century man. -

Carlo Scarpa Prize 2009 Jury Report

20th edition, 2009 Otaniemi Chapel Espoo, Helsinki, Finland Carlo Scarpa Prize A small masterpiece by the architects Kaija (1920-2001) and Heikki (1918-) Siren, the Otaniemi 2009 Chapel has stood since the mid-1900s in a Forest Glade on the hiGhest point oF the peninsula to Jury report which the distinGuished Helsinki University oF TechnoloGy was moved at around the same time. The masterly simplicity and transparency oF the buildinG draws revelation oF the sacred From nature and conFers sense and measure on a space that provides an educational experience, spiritual and social, cultural and musical, For the entire community oF Families and students. Nature, architecture and society thus come toGether in this remarkable crucible oF Form and liFe, the site to which the Jury has unanimously decided to award the seal oF the XX International Carlo Scarpa Prize For Gardens. The site embodies the Fundamental Features oF an anthropoloGy For which nature, and in particular the Forest, which covers three quarters oF Finland, is the principal source oF liFe, the most abidinG and proFound link with its history and a comFortinG, contemplative sanctuary. In the minute scale oF a work commissioned by a student association, in the subdued, oblique liGht oF its spaces, what strikes one most oF all is the primacy oF nature, the pantheism almost, which inForms the stones and the mosses, the sea Glimpsed beyond the trees and the houses, the bricks and the wood oF which the chapel is built and the Geometry oF parallel vertical lines throuGh which the Firs and the birches set scale and rhythm For human spaces. -

Aalto University Campus Journal, Pdf, Attachment

What will Otaniemi look More green on campus – University at the heart of the like in 2050? p. 20 transforming outdoor spaces p. 4 startup ecosystem p. 24 WINTER 2018–2019 3 AALTO UNIVERSITY CAMPUS Green and urban 4 From an ancient 26 village to an Into a new era innovation hub Map of Aalto University campus development 6 Otaniemi has over the years become an increasingly vibrant and open community, a truly unique place in Europe. From village The latest additions have made our campus a home for the 10 to campus entire Aalto community. A BRAND-NEW building invited the rest of the stu- of the community has been able to present their dents of the School of Arts, Design and Architec- ideas about the Centre’s services and functions. Architectural gems ture from Arabia to the Otaniemi campus from the Aside from the student restaurant and worksta- beginning of the new academic year 2018. In the tions, even minigolf and drone rental were added beginning of 2019, we will welcome the students on the wishlist. and staff of the School of Business from Töölö At the same time, a vision is being prepared to (pages 6–9). carry out the development of the campus up to 12 We are much closer to our dream of a university year 2050. This is where we need your help. On where different fields of science, identities, cultures, pages 20–23 you will be able to familiarize yourself and perspectives can meet in the same place. with three alternate future scenarios that we wish For students, this means new opportunities. -

PALE NORDIC ARCHITECTURE Why Are Our Walls So White?

PALE NORDIC ARCHITECTURE Why are our walls so white? BATCHELOR’S THESIS SISKO ANTTALAINEN AALTO UNIVERSITY PALE NORDIC ARCHITECTURE – WHY ARE OUR WALLS SO WHITE? – ABSTRACT The aim was to investigate the perception of whiteness in Nordic architecture and analyse the rea- sons behind the pale colour scheme in a public space context. The word pale was used alongside with white, since it gave broader possibilities to ponder over the topic. The geographical research area was framed to cover Sweden and Finland, although the search for underlying reasons extended beyond the borders of the North. Architecture was viewed as an entity, including both exteriors and interiors. The focus was on reasoning around the question “why” to arouse professional discourse about the often-unquestioned topic. Analysing the background of a commonly acknowledged phe- nomenon strives to make architects more conscious of the background of their aesthetics so that future decisions can be based on a more complex set of knowledge rather than leaning on tradition. Because of the wide demarcation of the research question, the project started with self-formulated hypothesis, after which they were thoroughly analysed. The formulated pre-assumptions were, that the Nordic paleness is, firstly, a consequence of misinterpreted past architecture. Moreover, natu- ral circumstances of the North, the symbolism connected to white and the tradition of canonising modernism were established as hypothesis. Lastly, architect education, combined with the tendency of prototyping with white materials were assumed to endorse the pale colour scheme. The misinter- pretations’ possible implication in the perception of whiteness was also examined as a part of the re- 1 search. -

Mattilanniemi Campus University Ofjyväskyläuniversity Jury Report Table of Contents 1

/2013 UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ PUBLIC DESIGN OY / J-PAINO OY MATTILANNIEMI CAMPUS ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN COMPETITION 25 JANUARY 2013 TO 25 APRIL 2013 JURY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 1 COMPETITION ASSIGNMENT................................................................................. 1.1 Organiser, character and aim of the competition ........................................... 1. Invitees ......................................................................................................................... 1. The competition jury and specialists ................................................................... 1. Competition rules ...................................................................................................... 1. Competition language ............................................................................................. 1. Compensation for participation ............................................................................ 2 THE COMPETITION INITIAL DATA .................................................................... .1 Background .................................................................................................................. . Town plan, urban structure and environment at present ............................ .................................................................................................... Traffic and parking 3 DESIGN GUIDELINES ................................................................................................... .1 The most important -

Tavasthem (1950)

En egen vrå i ett delat hem - hållbara lösningar för ökad trivsel i Erik Bryggmans (1891-1955) Tavasthem (1950) Katja Långvik, 23302 Pro gradu i konstvetenskap Handledare: Pia Wolff-Helminen och Kari Kotkavaara Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2017 ÅBO AKADEMI FAKULTETEN FÖR HUMANIORA, PSYKOLOGI OCH TEOLOGI Abstract avhandling pro gradu Ämne: Konstvetenskap Författare: Katja Långvik Arbetets titel: En egen vrå i ett delat hem – hållbara lösningar för ökad trivsel i Erik Bryggmans (1891 – 1955) Tavasthem (1950) Handledare: Pia Wolff-Helminen Handledare: Kari Kotkavaara Återuppbyggandet efter andra världskriget innebar ett stort behov av nya lösningar för boende. Antalet studerande i universitetsstäderna ökade markant och förändringar i bostadsidealen försämrade tillgången av underhyresalternativ. Studentkårer och nationer i Finland åtgärdade bostadsbristen genom att bygga egna studenthem. Åbo Akademis Studentkår lät bygga ett studenthem ritat av arkitekt Erik Bryggman (1891 – 1955) på Tavastgatan 22 i Åbo. På samma tomt fanns redan av samma arkitekt ritade Kårhus (1936), som förenades med studenthemmet. Av helheten behandlas i det här arbetet endast studenthemsdelen, som också kallas för Tavasthem (1950). Syftet med avhandlingen är att visa att Erik Bryggman i Tavasthem (1950) har lyckats skapa hållbara lösningar för ökad trivsel i studenthemmet. Genom form- och stilanalys identifieras stilistiska inslag och praktiska lösningar som arkitekten har valt för att öka trivseln i studentboendet inom ramen för byggprojektets ekonomiska förutsättningar. I avhandlingen söks svar på hur den funktionalistiska bostadsplaneringens ideal syns i de valda lösningarna och hur hållbara de varit ur ekonomiska, ekologiska och sociala synvinklar. Materialet granskas ur ett socialhistoriskt perspektiv och kontexten utgörs av uppkomsten av studentboende som en form av socialt byggande i Finland på 1940-talet. -

Functionalism Is a Finnish Thing

Oct 29, 2015 10:47 UTC Functionalism is a Finnish thing Finns like it practical and adjust their homes so that everyday life is as easy as possible. But don’t you get bored of that? Will functionalism continue to be important in the future? “Such beautiful functionalism!” The spontaneous remark by American dinner guests inspired me to look at my home through new eyes. Well, yes, the furniture is practical; there are hardly any items that are not needed and anything that might get in the way had been put away in closets for the visit. My guests had it right in the sense that our house is carefully measured. In our standardised house, the renovation projects have been designed to better take into account situations that come up in everyday life. Finns are used to demanding functionality. Kari Lappalainen, who has worked in the field for over 20 years and is the founder of an interior decoration agency bearing his name, sees this in his work. If an apartment lacks functionality, people will want to add it to their home, even if the house has to be refurbished. Lappalainen has worked on such projects before. A roof over your head or luxury? Lappalainen has excellent insight into what Finns look for in a home. He thinks Finns can be roughly divided into three groups. About one in five people think that the outcome really does not matter that much. They could be described with the phrase: “As long as I have a roof over my head.” “The clear majority, about 70 per cent of people, demand much more from the functions of the apartment and understand how many benefits the functionality of housing has in everyday life. -

Finland Chapter at Helsinki Cathedral

American Guild of Organists Marcussen & Søn organ (IV/84 ranks) Finland Chapter at Helsinki Cathedral Pipe Organ Encounters is an educational outreach program of the American Guild of Organists. Major funding for Pipe Organ Encounters is provided by the Associated Pipe Organ Builders of America. Additional support is provided by the American Institute of Organ builders, the Jordan Organ Endowment and the National Endowment for the Arts. Permanently endowed AGO scholarships are provided in memory of Charlene Brice Alexander, Robert S. Baker, Seth Bingham, Michael Cohen, Finland Chapter Margaret R. Curtin, Clarence Dickinson, Richard and Clara Mae Enright, Virgil Fox, Philip Hahn, Charles N. Henderson, Alfred E. Lunsford, Ruth Milliken, Bruce Prince-Joseph, Douglas Rafter, Ned Siebert, Mary K. Smith, and Martin M. Wick; and in honor of Anthony Baglivi, Philip E. Baker, Gordon and Naomi Rowley, Fred Swann, Morgan and Mary Simmons, and the Leupold Foundation. August 1 – 7, 2019 Scholarship Information Scholarship assistance is available through Helsinki, Finland the American Guild of Organists. Please American Guild of Organists, Organists, of Guild American 21 E 4 Aitanavain 01660 Vantaa 01660 Finland contact Finland POE Director Susanne Kujala ([email protected]) for information on initiating the online scholarship application process. In addition, students may also contact AGO chapters or religious institutions if financial aid is needed. An Overview Featured Instruments Student Registration POE is designed for teenagers, ages 13-18, who Helsinki Cathedral: Marcussen & Søn (1967, STEP ONE: Registration for POE have achieved an intermediate level of keyboard IV/84 ranks) is exclusively online. Please visit: proficiency. Previous organ study is not St.