Local Textile Trading Systems in Indonesia: an Example from Flores Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Totally Stitchin'

“Sarong Wrap Pants” With just a few easy steps, you can turn two squares of fabric and some ribbon into this season’s comfiest trend - a pair of sarong wrap pants! Created by: Kelly Laws, Marketing Project Manager Supplies: Baby Lock Sewing Machine or serger 2 yards 58” -60” wide lightweight knit fabric 5 yards 1” wide satin ribbon All-purpose thread Woolly thread for serger (OPTIONAL) Chalk Bodkin (or large safety pin) Tape measure Scissors Instructions: 1. Cut two rectangles of fabric 30” x 50”. 2. Fold them in half so you have two 30” x 25” pieces and stack them matching the fold edges. 3. Using the tape measure and chalk mark the following measurements on the fold edge. Totally Stitchin’ Project: Sarong Wrap Pants Page 1 of 3 4. Cut a curved line and remove the top corner piece. 5. Open the rectangles and match the right side of the fabric. 6. Stitch the two pieces together at the curve. This will form the crotch seam of the wrap pants. 7. Find the edges with the seams. These will be the center front and center back waist seams. Fold over 1-1/2” to form the waist line casing. Stitch along the edge leaving the ends open to run the ribbon through. Totally Stitchin’ Project: Sarong Wrap Pants Page 2 of 3 8. To finish the edges on the wrap pants use a three thread rolled hem with the serger or a small zigzag stitch with the sewing machine along the sides and hem. For a softer hem use woolly nylon in both loopers of the serger. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1943-03-14

Ration Calendar Light Snow OA8 "AU o01lpoa • ulol... ,..,••• 1/ FllEL OIL OOUpGD • oxpl,.. April 1,8, IOWA: Licbt.Dow In north 00,.,.B8 o.u,.n 25 ...plr.. Mar•• 11/ liDd t porUou 8UOAIC .oupon II 'ICpl". ~r.. "b 161 THE DAILY IOWAN HROIIN, •• ",..n 17 upl'lI Iv.. J(' cold., loda,. Iowa City's Morning Newspaper fIVE CENTS IOWA CITY, IOWA SUNDAY, MARCH 14, 1943 VOLUME XLID NUMBER 144 e I e al 5 n, 1 U.S.·TRAINED CHINESE AIRMEN NOW FIGHT SIDE BY SIDE WITH YANKS Visiting Eden Warns Allies of Long Road Ador Very III To Victory as Talks With F.D.R. Begin Unloads 1,000 • War, Global Security Tons of Bombs Germans Gain Will Be Chief Points Of Vital Conferences Upon Railways WASHINGTON (AP) - Warn- On Kharkov ing that "we'vc gol a long way yct to go" on the road to victory, Pummels Supply Route Reds Admit Situation Anthony Eden, British foreign sec To Coastline Troops l retary, ha tened to get tOGether AJong Somme, Seine ISerious as Enemy Iwith President Roosevelt last night on the vast problcrru of war Advances New Units I LO 'DO~ (AP)-Thc RAF llnd global. ecurity. • h'oPP d mor thlln 1, ton LONDON, Sunday (AP)-Gcr The president invited Eden for J[ bomb on E "pn Frid , man troops gained fresh ground in a dinner and a lalk. the White the flaming right for Kharkov. a Housc announced. Anothcr guest night, and y . t rdllY 11ft rnoo;, midnight Moscow bulletin an was John G. Winant, the Ameri whil fil't' till w re l'1Il>ing nounced today, and Russian field can ambas. -

Sarong Tie-Dye

Sarong Tie-Dye Materials and Technique: 2 yards very fine muslin, about 59 inches wide Clear rubber bands Brown dye (instructions below) Pink dye (instructions below) A-clamp 1. Hem the raw cut edges of the muslin, and fold into quarters. Press flat. Pleat or "accordion" the fabric so your folds run from the folded end to the hemmed end. The pleats should be about 2 inches deep. 2. Wrap a rubber band around each end of your pleated fabric, about 2 inches in. Wrap a rubber band around the center. Wrap each rubber band around itself as many times as you can. For a pattern with more stripes, add more rubber bands, about every 2 inches; the portion of the fabric under the rubber band won't absorb the dye. 3. Create the circle-design border along the ends of the sarong: Working a few inches from the hemmed side, pinch one of the pleats and secure the bunched fabric with a rubber band. Use another rubber band to tie off the next pleat, right next to the first rubber band. Repeat for all the pleats in that "row." To stagger your dots, flip fabric over and repeat the pinching technique in a row, an inch down from the first row. 4. Mix the dyes: For brown dye, combine 3 quarts warm, not hot, water, 1 cup table salt, and 1 (8- ounce) bottle dark brown fluid Rit dye #25 in a large nonreactive pot. For darker colors, add more dye. For pink dye, combine 3 quarts warm water, 1 cup table salt, 1 tablespoon mauve fluid Rit dye #19, and 1 teaspoon tan fluid Rit dye #16 in a large nonreactive pot. -

Ancient Civilizations Huge Infl Uence

India the rich ethnic mix, and changing allegiances have also had a • Ancient Civilizations huge infl uence. Furthermore, while peoples from Central Asia • The Early Historical Period brought a range of textile designs and modes of dress with them, the strongest tradition (as in practically every traditional soci- • The Gupta Period ety), for women as well as men, is the draping and wrapping of • The Arrival of Islam cloth, for uncut, unstitched fabric is considered pure, sacred, and powerful. • The Mughal Empire • Colonial Period ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS • Regional Dress Harappan statues, which have been dated to approximately 3000 b.c.e. , depict the garments worn by the most ancient Indi- • The Modern Period ans. A priestlike bearded man is shown wearing a togalike robe that leaves the right shoulder and arm bare; on his forearm is an armlet, and on his head is a coronet with a central circular decora- ndia extends from the high Himalayas in the northeast to tion. Th e robe appears to be printed or, more likely, embroidered I the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges in the northwest. Th e or appliquéd in a trefoil pattern. Th e trefoil motifs have holes at major rivers—the Indus, Ganges, and Yamuna—spring from the the centers of the three circles, suggesting that stone or colored high, snowy mountains, which were, for the area’s ancient inhab- faience may have been embedded there. Harappan female fi gures itants, the home of the gods and of purity, and where the great are scantily clad. A naked female with heavy bangles on one arm, sages meditated. -

Infinite Ways Crocheted Sarong

Infinite Ways Crocheted Sarong "This piece could be the most versatile cover-up that you’ve ever owned. The unique and airy sarong can be worn so many ways! Use it as a striking shawl or make it into a dress or skirt. You choose how much you want to cover up and what style you’re in the mood for. Plus, it’s fun to crochet as it uses a super simple stitch pattern. Who knew making a simple, airy rectangle could turn into a summer vacation staple?" You can wear this Sarong in so many different ways! By using a large hook, and cotton yarn with a diamond mesh stitch pattern it worked out to be light, easy to tie, and fun to wear in an “infinite” number of ways. Here we have blanket sarong…. Here we have dress sarong….. Here we have skirt sarong… And the scarf sarong… Halter Dress Style…. So many ways to wear it, no? And it’s just a rectangle! You will need: Size L 8.0 mm crochet hook 3 skeins of Lion Brand 24/7 Cotton Worsted Weight Yarn in White (186 yards, 100g per skein) Pattern uses approximately 300 g 1 skein of Lion Brand 24/7 Cotton Worsted Weight Yarn in Black (186 yards, 100g per skein) Pattern uses approximately 30 g Scissors Tapestry Needle to weave in ends Skill Level: Easy + Skills & Abbreviations: ch – chain sc – single crochet st – stitch sk – skip Gauge: Just over 2 ½ stitches per inch, just under 1 row per inch Measurements: One size fits most 64 inches long X 36 inches wide Notes: This sarong is created with a series of chain stitches and single crochet stitches. -

Traditional Clothes of the Country(Joint

Message froM PRESIDENT Dear Rotaractors, Warm Rotaract Greetings from Rotaract Club of Thane North (RID 3142- India) We are glad sharing an editorial space with you and find great pleasure introducing the Traditional attire of our country. As you know India is a diverse country and has 29 states and 7 union territories. Every state has their own diverse language and traditional attire. We even have diversity in religion maximum people following Hinduism and the rest being Islam, Christianity and Sikhism; leave aside the other tribes which have their own traditional attire. Living in such a diversified country it is difficult to write about the entire traditional clothing, but here I will just try giving you a glimpse of the same. For men, traditional clothes are the Achkan/Sherwani, Bandhgala, Lungi, Kurta, Angarkha, Jama and Dhoti or Pajama. Additionally, recently pants and shirts have been accepted as traditional Indian dress by the Government of India. In India, women's clothing varies widely and is closely associated with the local culture, religion and climate. Traditional Indian clothing for women in the north and east are saris worn with choli tops; a long skirt called a lehenga or pavada worn with choli and a dupatta scarf to create an ensemble called a gagra choli; or salwar kameez suits, while many south Indian women traditionally wear sari and children wear pattu langa. Saris made out of silk are considered the most elegant. Mumbai, formerly known as Bombay, is one of India's fashion capitals. In many rural parts of India, traditional clothes is worn. -

Non-Iconic Movements of Tradition in Keralite Classical Dance Justine Lemos

Document generated on 09/26/2021 10:09 p.m. Recherches sémiotiques Semiotic Inquiry Radical Recreation: Non-Iconic Movements of Tradition in Keralite Classical Dance Justine Lemos Recherches anthropologiques Article abstract Anthropological Inquiries Many studies assume that dance develops as a bearer of tradition through Volume 32, Number 1-2-3, 2012 iconic continuity (Downey 2005; Hahn 2007; Meduri 1996, 2004; Srinivasan 2007, 2011, Zarrilli 2000). In some such studies, lapses in Iconic continuity are URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1027772ar highlighted to demonstrate how “tradition” is “constructed”, lacking DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1027772ar substantive historical character or continuity (Meduri 1996; Srinivasan 2007, 2012). In the case of Mohiniyattam – a classical dance of Kerala, India – understanding the form’s tradition as built on Iconic transfers of semiotic See table of contents content does not account for the overarching trajectory of the forms’ history. Iconic replication of the form as it passed from teacher to student was largely absent in its recreation in the early 20th century. Simply, there were very few Publisher(s) dancers available to teach the older practice to new dancers in the 1960s. And yet, Mohiniyattam dance is certainly considered to be a “traditional” style to its Association canadienne de sémiotique / Canadian Semiotic Association practitioners. Throughout this paper I argue that the use of Peircean categories to understand the semiotic processes of Mohiniyattam’s reinvention in the 20th ISSN century allows us to reconsider tradition as a matter of Iconic continuity. In 0229-8651 (print) particular, an examination of transfers of repertoire in the early 20th century 1923-9920 (digital) demonstrates that the “traditional” and “authentic” character of this dance style resides in semeiotic processes beyond Iconic reiteration; specifically, the “traditional” character of Mohiniyattam is Indexical and Symbolic in nature. -

Ancient Indian Texts of Knowledge and Wisdom

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com The Saree - The Very Essence of Indian Womanhood Copyright © 2013, DollsofIndia A saree or sari is a long strip of unstitched cloth, which is draped by Indian women – it practically typifies Indian women and showcases the vast diversity of Indian culture as a whole. The word "Sari" is derived from the Sanskrit and the Prakrit (pre-Sanskrit language) root, "Sati", which means, "strip of fabric". Interestingly, the Buddhist Jain works, the Jatakas, describe women’s apparel, called the "Sattika", which could well have been similar to the present-day saree. Another fact is that the end of the saree that hangs downward from the shoulder is called the Pallav. Experts believe that the name came to be during the reign of the Pallavas, the ruling dynasty of ancient Tamilnadu. A saree typically ranges from six to nine yards in length and can be worn in several ways, depending upon the native of the wearer and her outlook on current fashion. Usually, a saree is tucked in at the waist and is then wrapped around the body with pleats in the center, the other end draped loosely over the left shoulder, showing the midriff. This apparel is also popular in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Singapore and Malaysia. This very feminine garment is worn over a petticoat, also referred to as a lehenga in the North, a paavaadai in the South, a parkar or ghaghra in the West and a shaya in the East. It is worn along with a bodice or blouse, called the choli (in North India) or ravikkai (in South India). -

HOLDERSTEADY 1 (Last Bred to Big Stick Lindy on March 27, 2017) Bay Mare - Foaled May 3, 2005 - Freeze Brand #6CB99

Consigned by: Black Creek Farm, Grabill, IN HOLDERSTEADY 1 (Last bred to Big Stick Lindy on March 27, 2017) Bay Mare - Foaled May 3, 2005 - Freeze Brand #6CB99 Speedy Somolli 3, 1:55 Baltic Speed 3, 1:56 ....................... Sugar Frosting 2, 2:13h Dakota Spur 3, 1:57.4 ................. Dream Of Glory 3, 1:57.2 Crystal River 3, 2:03.3f ................... Happy Time 2:07.1f HOLDERSTEADY Stars Pride 1:57.1 Super Bowl 3, 1:56.2 ....................... Pillow Talk 3, 2:11.1h Harliana Hanover ......................... Hickory Smoke 4, T1:58.2 Hilary Hanover 3, T2:04.3 ............... Highland Lassie 3, T2:05.4 By DAKOTA SPUR 3, 1:57.4 ($47,111). Sire of 1 in 1:55 - 34 in 2:00 including DAKOTAS FINAL 3, 1:57.1- ’10 ($266,533); CC MISTER C 3, 1:58.2f, 1:54.2- ’10 ($251,644); MYCENAE BLUEGRASS 2, 2:01.4, 3, 1:58.3, 1:57.3f- ’08 ($188,110); WAU EEGL BLUEGRASS 2, 2:00.4s, 3, 1:58.1s- ’01 ($184,349) etc. 1st dam HARLIANA HANOVER, by SUPER BOWL 3, 1:56.2. Dam of 6 winners including- GIRL NAMED HARLEY (m, Thirty Two) 2, 2:07h- ’02 ($4,543) 3 wins. At 2, winner of PA Fair S. div at Gratz, div at Honesdale, div at Meadville; second in PA Fair S. div at Wattsburg. Bubbie Lovestotrot (m, Dancers Victory) 3, 2:05.1h- ’02 ($19,990) 3 wins. Taperoo (h, Baltic Speed) 4, 2:00.1h- ’96 ($16,187) 4 wins, (p, ($67)). -

2021-22 District Attendance Boundary Map (PDF)

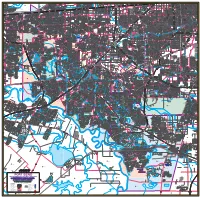

CHARTREUSE WY BANNER SHADOW ARMSTRONG HAHNECK HORNBEAM LOUVRE LN WINGT ELLIS WINGDALE WOODMILL OVERTURE FORK CT DREW ALBANS PARK CLAYTON ROYAL FAIRWICK CT CT WTRSTN CT FIDDLERS BRIM CT GRAY RD PL CRICKET WD G 13100 THISTLEMT REY PIN VLLY 11500 ST. LAUREN WOODCHASE EZ TAG ONLY EL CAMINO PFEIFFER WDS SPRUCE WESTPARK DEL DARTMOUTH ACADEMY ACE WESTPARK SHEER WTR 9900 ARC 610 ADE FLD CT EDISON PIN GRN DAHLIA FLD WY GALL 10500 SUNSET BLVD GLN MAR N. ANT RDG PARK OAK OAK PK SYRACUSE PARK 3800 GERRARDS 5400 13500 L WEST HILLC TOLL PARK PRKRDG GLN 3700WROXTON MAL CROSS 3800 WILDE DALRYMPLE SHDW WICK 10700 OAKBRRY E OCEE SUNSET Buffalo CT INDIGO HILL LN HIGHLANDER CHADWELL GLN LEHIGH GALLANT TANGEL NEWMT OSAGE MNT 12600 ASHFORD PT G 7700 1ST ARENA SAGE SHADOW CV GRAY Holmquist TWIN 12600 WALDO NOTTINGHAM ARTDALE CT FAIR LN DERRIL E N. SUNSET DOWNS N 3800 3600 BROADGLEN PLAZA 14600 JEANETTA EDISON PASO 3900 D P&R 5500 MAPLE CLAYTON TIMBER WY RDG CT WESTOFFICE TRL Challenge PL WDS BLVD BIST VALE M LEHIGH NOTTINGHAM MAN LUTON IVY BLOSSOM LN HUNTON BTTRSTN WAGLEY ELM CT A COACHPOINT 8600 N IDLEWD KINGSTON CT GERRARDS CROSS 13100 OR 273 MACON 5600 HOV PRK LN A S. 5600 NORTHWESTERN 5500 RAVENLOCH ENSLEY WD 11300 WESTPARK TOLLWAY 14TH QUENBY BURY 10300 CT WILLIAMS SAXON TEASEL ROCK E 5500 N. ASHFORD VILLA LN WY WOODBRK ARCHWY S. RICE 5500 3500 ASCOT BARKER WILLOWFORD SCHILLER PRK SHADOW CV RO 11400 P&R 5600 YMCA c 3500 S BARKER DAM BONNEBRIDGE WY ANDERSON 5400 KEY MAPS 2020 3600 McDONALD EMORY GALLANT 12700 SHADY 8800 H OLD STABLE CT Liberty ROYALTON E. -

The Legacy of Yarn Dyed Cotton Lungis of Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu: a Case Study Vasantha M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2016 The Legacy of Yarn Dyed Cotton Lungis of Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu: A Case Study Vasantha M. Dr. National Institute of Fashion Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons M., Vasantha Dr., "The Legacy of Yarn Dyed Cotton Lungis of Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu: A Case Study" (2016). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 969. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/969 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Crosscurrents: Land, Labor, and the Port. Textile Society of America’s 15th Biennial Symposium. Savannah, GA, October 19-23, 2016. 335 The Legacy of Yarn Dyed Cotton Lungis of Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu: A Case Study Dr. M. Vasantha Associate Professor, National Institute of Fashion Technology, Chennai [email protected] Woven cotton textiles of India are ancient, diverse, and steeped in tradition, an amalgam of different ethnic influences, much like reflection of the country itself. Having had the advantage of possessing a unique raw material for more than 5000 years of recorded history, she has been a benefactress of her rich cotton textile heritage to the entire world.