Part 6: Region-Specific Governance and Conflict Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recognition and Rebel Authority: Elite-Grassroots Relations in Myanmar’S Ethnic Insurgencies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Goldsmiths Research Online Manuscript submission to Contemporary Politics - Original Article Title: Recognition and Rebel Authority: Elite-Grassroots Relations in Myanmar’s Ethnic Insurgencies Author: David Brenner: [email protected] Lecturer in International Relations Department of Politics University of Surrey Guildford, GU2 7XH, United Kingdom Research Associate Global South Unit Department of International Relations The London School of Economics (LSE) Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom Recognition and Rebel Authority: Elite-Grassroots Relations in Myanmar’s Ethnic Insurgencies ABSTRACT: This article contributes to the emerging scholarship on the internal politics of non-state armed groups and rebel governance by asking how rival rebel leaders capture and lose legitimacy within their own movement. It explores this question by drawing on critical social theory and ethnographic field research on Myanmar’s most important ethnic armed groups: the Karen and Kachin insurgencies. The article finds that authority relations between elites and grassroots in these movements are not primarily linked to the distributional outcomes of their insurgent social orders, as a contractualist understanding of rebel governance would suggest. It is argued that the authority of rebel leaders in both analysed movements rather depends on whether they address their grassroots’ claim to due and proper recognition, enabling the latter to derive self-perceived positive social identities through affiliation to the insurgent collective. This contributes to our understanding of the role that authority relations between differently situated elite and non-elite insurgents play in the factional contestation within rebel movements. -

Competing Forms of Sovereignty in the Karen State of Myanmar

Competing forms of sovereignty in the Karen state of Myanmar ISEAS Working Paper #1 2013 By: Su-Ann Oh1 Email: [email protected] Visiting Research Fellow Regional Economic Studies Programme Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 1 The ISEAS Working Paper Series is published electronically by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each Working Paper. Papers in this series are preliminary in nature and are intended to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The Editorial Committee accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed, which rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be produced in any form without permission. Comments are welcomed and may be sent to the author(s) Citations of this electronic publication should be made in the following manner: Author(s), “Title,” ISEAS Working Paper on “…”, No. #, Date, www.iseas.edu.sg Working Paper Editorial Committee Lee Hock Guan (editor) Terence Chong Lee Poh Onn Tin Maung Maung Than Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30, Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Homepage: www.iseas.edu.sg Introduction The Thai-Burmese border, represented by an innocuous line on a map, is more than a marker of geographical space. It articulates the territorial limits of sovereignty2 and represents the ideology behind the doctrine of modern nation-states. Accordingly, every political state must have a definite territorial boundary which corresponds with differences of culture and language. Moreover, territorial sovereignty is absolute, indivisible and mutually exclusive, as set out by the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Social Assessment for Ayeyarwady Region and Shan State

AND DEVELOPMENT May 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SOCIAL ASSESSMENT FOR AYEYARWADY REGION AND SHAN STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition 1 Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement May 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... 10 List of BOXES ................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Introduction and Background....................................................................................................... 11 1 Objectives of the Social Assessment ................................................................................................11 2 Project Description ..........................................................................................................................11 3 Relevant Country and Sector Context..............................................................................................12 3.1 -

The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census SHAN STATE, KYAUKME DISTRICT Namtu Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census SHAN STATE, KYAUKME DISTRICT Namtu Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Shan State, Kyaukme District Namtu Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Shan State, showing the townships Namtu Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 50,423 2 Population males 24,448 (48.5%) Population females 25,975 (51.5%) Percentage of urban population 26.4% Area (Km2) 1,689.0 3 Population density (per Km2) 29.9 persons Median age 25.8 years Number of wards 2 Number of village tracts 21 Number of private households 11,641 Percentage of female headed households 27.5% Mean household size 4.2 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 32.6% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 62.3% Elderly population (65+ years) 5.1% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 60.5 Child dependency ratio 52.3 Old dependency ratio 8.2 Ageing index 15.6 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 94 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 67.5% Male 71.8% Female 63.7% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 3,082 6.1 Walking 1,035 2.1 Seeing 1,374 2.7 Hearing 1,137 2.3 Remembering 976 1.9 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 28,204 71.4 Associate Scrutiny -

Transnational Ethnic Communities and Rebel Groups' Strategies in a Civil Conflict

Transnational Ethnic Communities and Rebel Groups’ Strategies in a Civil Conflict The case of the Karen National Union rebellion in Myanmar Bethsabée Souris University College London (UCL) 2020 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science I, Bethsabée Souris, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis 1 2 Abstract Few studies have systematically analysed how transnational ethnic kin groups affect the behaviour of domestic ethnic groups in an insurgency, in particular how they have an effect on the types of activities they conduct and their targets. The research question of this study is: What are the mechanisms through which transnational ethnic kin groups influence the domestic rebel ethnic group’s strategies? This thesis analyses the influence of transnational communities on domestic challengers to the state as a two-step process. First, it investigates under which conditions transnational ethnic kin groups provide political and economic support to the rebel ethnic group. It shows that networks between rebel groups and transnational communities, which can enable the diffusion of the rebel group’s conflict frames, are key to ensure transnational support. Second, it examines how such transnational support can influence rebel groups’ strategies. It shows that central to our understanding of rebel groups’ strategies is the cohesion (or lack thereof) of the rebel group. Furthermore, it identifies two sources of rebel group’s fragmentation: the state counter-insurgency strategies, and transnational support. The interaction of these two factors can contribute to the fragmentation of the group and in turn to a shift in the strategies it conducts. -

The-Contested-Corner

200X270 mm sun 9 mm 200X270 mm ISBN 978-616-91408-1-8 9 786169 140818 56-06-011_COVER_V=G ClassicArtCard-cs6 The Contested Corners of Asia: Subnational Conflict and International Development Assistance Thomas Parks Nat Colletta Ben Oppenheim Authors Thomas Parks, Nat Colletta, Ben Oppenheim Contributing Authors Adam Burke, Patrick Barron Research Team (in alphabetical order) Fermin Adriano, Jularat Damrongviteetham, Haironesah Domado, Pharawee Koletschka, Anthea Mulakala, Kharisma Nugroho, Don Pathan, Ora-orn Poocharoen, Erman Rahman, Steven Rood, Pauline Tweedie, Hak-Kwong Yip Advisory Panel Judith Dunbar, James Fearon, (in alphabetical order) Nils Gilman, Bruce Jones, Anthony LaViña, Neil Levine, Stephan Massing, James Putzel, Rizal Sukma, Tom Wingfield World Bank Counterparts Ingo Wiederhofer, Markus Kostner, Adrian Morel, Matthew Stephens, Pamornrat Tansanguanwong, Ed Bell, Florian Kitt, Holly Wellborn Benner Supporting Team Ann Bishop (editor), Landry Dunand, Anone Saetaeo (layout), Kaptan Jungteerapanich, Gobie Rajalingam Lead Expert Nat Colletta Project Manager Thomas Parks Research Specialist and Perception Survey Lead Ben Oppenheim Research Methodologist Hak-Kwong Yip Specialist in ODA to Conflict Areas Anthea Mulakala This study has been co-financed by the State and Peacebuilding Fund (SPF) of the World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Additional funding for this study was provided by UK Aid from the UK Government. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of The Asia Foundation or the funders. -

Burma's Northern Shan State and Prospects for Peace

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE PEACEBRIEF234 United States Institute of Peace • www.usip.org • Tel. 202.457.1700 • @usip September 2017 DAVID SCOTT MATHIESON Burma’s Northern Shan State Email: [email protected] and Prospects for Peace Summary • Increased armed conflict between the Burmese Army and several ethnic armed organizations in northern Shan State threaten the nationwide peace process. • Thousands of civilians have been displaced, human rights violations have been perpetrated by all parties, and humanitarian assistance is being increasingly blocked by Burmese security forces. • Illicit economic activity—including extensive opium and heroin production as well as transport of amphetamine stimulants to China and to other parts of Burma—has helped fuel the conflict. • The role of China as interlocutor between the government, the military, and armed actors in the north has increased markedly in recent months. • Reconciliation will require diverse advocacy approaches on the part of international actors toward the civilian government, the Tatmadaw, ethnic armed groups, and civil society. To facili- tate a genuinely inclusive peace process, all parties need to be encouraged to expand dialogue and approach talks without precondition. Even as Burma has “transitioned from decades Introduction of civil war and military rule Even as Burma has transitioned—beginning in late 2010—from decades of civil war and military to greater democracy, long- rule to greater democracy, long-standing and widespread armed conflict has resumed between several ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) and the Burmese armed forces (Tatmadaw). Early in standing and widespread 2011, a 1994 ceasefire agreement broke down as relations deterioriated in the wake of the National armed conflict has resumed.” League for Democracy government’s refusal to permit Kachin political parties to participate in the elections that ended the era of military rule in the country. -

Chapter 3, Section 1 – China and Continental Southeast Asia.Pdf

CHAPTER 3 CHINA AND THE WORLD SECTION 1: CHINA AND CONTINENTAL SOUTHEAST ASIA Key Findings • China’s pursuit of strategic and economic interests in Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos often jeopardizes regional environmental conditions, threatens government ac- countability, and undermines commercial opportunities for U.S. firms. • China has promoted a model of development in continental Southeast Asia that focuses on economic growth, to the exclu- sion of political liberalization and social capacity building. This model runs counter to U.S. geopolitical and business interests as Chinese business practices place U.S. firms at a disadvantage in some of Southeast Asia’s fastest-growing economies, particu- larly through behavior that facilitates corruption. • China pursues several complementary goals in continental Southeast Asia, including bypassing the Strait of Malacca via an overland route in Burma, constructing north-south infra- structure networks linking Kunming to Singapore through Laos, Thailand, Burma, and Vietnam, and increasing export opportunities in the region. The Chinese government also de- sires to increase control and leverage over Burma along its 1,370-mile-long border, which is both porous and the setting for conflict between ethnic armed groups (EAGs) and the Burmese military. Chinese firms have invested in exploiting natural re- sources, particularly jade in Burma, agricultural land in Laos, and hydropower resources in Burma and along the Mekong Riv- er. China also seeks closer relations with Thailand, a U.S. treaty ally, particularly through military cooperation. • As much as 82 percent of Chinese imported oil is shipped through the Strait of Malacca making it vulnerable to disrup- tion. -

Geology & Mineral Resources of Myanmar

Geology & Mineral Resources of Myanmar KYAW KYAW OHN Assistant Director (Geologist) DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY AND MINERAL EXPLORATION MINISTRY OF MINES 1 Introduction Organization Morpho-Tectonic Geology Mineral Occurrence Investment Cooperation Conclusion Belts of Setting of & Mining Activities Opportunities with Myanmar Myanmar in Myanmar International Myanmar is endowed with resources of arable land, natural gas, mineral deposits, fisheries, forestry and manpower. 2 Introduction Organization Morpho-Tectonic Geology Mineral Occurrence Investment Cooperation Conclusion Belts of Setting of & Mining Activities Opportunities with Myanmar Myanmar in Myanmar International Area : 678528 sq.km Coast Line : 2100 km Border : 4000 km NS Extend : 2200 km EW Extend : 950 km Population : >51millions(est:) Region : 7 State: : 7 Location : 10º N to 28º 30' 92º 30' E to 101º30' 3 Introduction Organization Morpho-Tectonic Geology Mineral Occurrence Investment Cooperation Conclusion Belts of Setting of & Mining Activities Opportunities with Myanmar Myanmar in Myanmar International Union Minister Deputy Minister No.(1) No.(2) Myanmar Myanmar Department of Geological Department Mining Mining Gems Pearl Survey &Mineral of Enterprise Enterprise Enterprise Enterprise Exploration Mines Lead Coal Gold Gems, Pearl Geological Mineral Zinc Lime stone Tin Jade Breeding Survey Policy Silver Industrial Tungsten & Cultivating Mineral formulation, Copper Minerals Rare Earth Jewelry Exploration Regulation Iron Manganese Titanium Laboratory measures Nickel Decorative -

Myanmar Overall Score: 53

Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2019 Myanmar Overall score: 53 I. Industry participation in policy development: required pictures and old pictures were still found The National Tobacco Control Board has been in the market. No action was found to be taken. constituted under the national tobacco control The Myanmar government is open and welcoming law of 2006. Although representatives from to foreign investment including BAT and JTI, and tobacco industries are not present in the Board most recently to Burma Tobacco Trading Co. for as members, the government will consider cigar production and tobacco growing. proposals from the tobacco industry in setting or implementing public health policies in relation IV. Unnecessary interaction with the tobacco to tobacco control. In 2017 the tobacco industry industry: There are no publicly available reports submitted a tobacco tax proposal for the tax of government officials attending social functions reform to the Internal Revenue Department and of the tobacco industry. EUROCHAM Myanmar Ministry of Planning and Finance. The Ministry has an anti-Illicit Trade group which has BAT acknowledged the receipt of the proposal and as a member. The objective of this group is “to co- indicated it will include it for consideration. ordinate regular consultation meetings between the group and the authorized government officials II. Tobacco industry-related CSR activities: A local to develop a shared understanding of challenges Cigarette Company, called Myanmar Kokang and issues.” Company Ltd. (MMK Cigarette Factory), at Muse, Northern Shan State, provided sponsorship V. Procedure for transparency measures: There is no through its distributor, Hexa Power Company Ltd., mechanism or rules for disclosure of government for the mini marathon and public walking event meetings with the tobacco industry. -

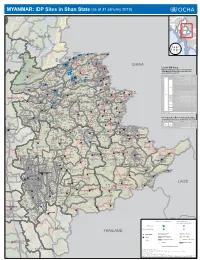

IDP Sites in Shan State (As of 31 January 2019)

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Shan State (as of 31 January 2019) BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND Pang Hseng Man Kin (Kyu Koke) Monekoe SAGAING Kone Ma Na Maw Hteik 21 Nawt Ko Pu Wan Nam Kyar Mon Hon Tee Yi Hku Ngar Oe Nam War Manhlyoe 22 23 Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan Shwe Kyaung Kone U Yin Pu Nam Kat 36 (Manhero) Man Hin ☇ Muse Pa Kon War Yawng San Hsar Muse Konkyan Kun Taw 37 Man Mei ☇ Long Gam Man Ton ☇34 Tar Ku Ti Thea Chaung Namhkan 35 KonkyanTar Shan ☇ Man Set Kyu Pat 11 26 28 Au Myar Loi Mun Ton Bar 27 Yae Le Lin Lai 25 29 Hsi Hsar Hsin Keng Yan Long Keng CHINA Ho Nar Pang Mawng Long Htan Baing Law Se Long Nar Hpai Pwe Za Meik Khaw Taw HumLaukkaing Htin List of IDP Sites Aw Kar Pang Mu Shwe Htu Namhkan Kawng Hkam Nar Lel Se Kin 14 Bar Hpan Man Tet 15 Man Kyu Baing Bin Yan Bo (Lower) Nam Hum Tar Pong Ho Maw Ho Et Kyar Ti Lin Data provided by the Camp Coordination and Pang Hkan Hing Man Nar Hin Lai 4 Kutkai Nam Hu Man Sat Man Aw Mar Li Lint Ton Kwar 24 Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster based on Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Ho Pang 8 Hseng Hkawng Laukkaing Mabein 17 Man Hwei Si Ping Man Kaw Kaw Yi Hon Gyet Hopong Hpar Pyint Nar Ngu Long Htan update of 31 January 2018 Lawt Naw 9 Hko Tar Ma Waw 10 Tarmoenye Say Kaw Man Long Maw Han Loi Kan Ban Nwet Pying Kut Mabein Su Yway Namtit No.