MA Thesis Veronika Goišová

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix Wuthering Heights Screen Adaptations

Appendix Wuthering Heights Screen Adaptations Abismos de Pasión (1953) Directed by Luis Buñuel [Film]. Mexico: Producciones Tepeyac. Arashi Ga Oka (1988) Directed by Kiju Yoshida [Film]. Japan: Mediactuel, Saison Group, Seiyu Production, Toho. Cime Tempestose (2004) Directed by Fabrizio Costa [Television serial]. Italy: Titanus. Cumbres Borrascosas (1979) Directed by Ernesto Alonso and Karlos Velázquez [Telenovela]. Mexico: Televisa S. A. de C. V. Dil Diya Dard Liya (1966) Directed by Abdul Rashid Kardar [Film]. India: Kary Productions. Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1992) Directed by Peter Kosminsky [Film]. UK/USA: Paramount Pictures. Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1998) Directed by David Skynner [Television serial]. UK: ITV, Masterpiece Theatre, PBS. Hihintayin Kita Sa Langit (1991) Directed by Carlos Siguion-Reyna [Film]. Philippines: Reynafilms. Hurlevent (1985) Directed by Jacques Rivette [Film]. France: La Cécilia, Renn Productions, Ministère de la Culture de la Republique Française. Ölmeyen Ask (1966) Directed by Metin Erksan [Film]. Turkey: Arzu Film. ‘The Spanish Inquisition’ [episode 15] (1970). Monty Python’s Flying Circus [Television series]. Directed by Ian MacNaughton. UK: BBC. Wuthering Heights (1920) Directed by A. V. Bramble [Film]. UK: Ideal Films Ltd. Wuthering Heights (1939) Directed by William Wyler [Film]. USA: United Artists/ MGM. Wuthering Heights (1948) Directed by George More O’Ferrall [Television serial]. UK: BBC. Wuthering Heights (1953) Directed by Rudolph Cartier [Television serial]. UK: BBC. Wuthering Heights (1962) Directed by Rudolph Cartier [Television serial]. UK: BBC. Wuthering Heights (1967) Directed by Peter Sasdy [Television serial]. UK: BBC. Wuthering Heights (1970) Directed by Robert Fuest [Film]. UK: American International Pictures. Wuthering Heights (1978) Directed by Peter Hammond [Television serial]. -

Thesisfinalfinal27022017 This Version for Submission

NEGATIVE CAPABILITY: DOCUMENTARY AND POLITICAL WITHDRAWAL SIMON GENNARD A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON 2017 CONTENTS ABSTRACT 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 4 INTRODUCTION 5 EXIT STRATEGIES CHAPTER ONE 16 NAMING AS SUCH CHAPTER TWO 32 ‘THE PURE FLIGHT OF A METAL BAR CRASHING THROUGH A WINDOW’ CHAPTER THREE 47 TROUBLE IN THE IMAGE WORLD CHAPTER FOUR 65 ‘THE QUEER OPAQUE’ CONCLUSION 83 BIBLIOGRAPHY 86 ILLUSTRATIONS 92 !1 ABSTRACT This thesis thinks with, alongside, and against several theories of political withdrawal that have emerged during the past three decades as they have been taken up by artists working with documentary video. Political withdrawal here refers to a set of tactics that position themselves in opposition to existing models of belonging, civic engagement, and contestation. The context in which this study takes place is one in which qualifying for citizenship in the liberal western state increasingly requires one remain transparent, docile, and willing to acquiesce to whatever demands for information the state may make. In response to these conditions, the theories and artworks examined in this thesis all propose arguments in favour of anonymity, opacity, and indeterminacy. Situating itself, sometimes uncomfortably, within the archives of feminist, queer, and anarchist thought, this thesis engages with selected video works by Martha Rosler, Bernadette Corporation, Hito Steyerl, and Zach Blas in order to understand the ways in which withdrawal may constitute a generative framework for enabling meaningful social change. These video works are here described as documentary, but not in the conventional sense that they are objective or transparent attempts to capture or record actual fact. -

Dear Secretary Salazar: I Strongly

Dear Secretary Salazar: I strongly oppose the Bush administration's illegal and illogical regulations under Section 4(d) and Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, which reduce protections to polar bears and create an exemption for greenhouse gas emissions. I request that you revoke these regulations immediately, within the 60-day window provided by Congress for their removal. The Endangered Species Act has a proven track record of success at reducing all threats to species, and it makes absolutely no sense, scientifically or legally, to exempt greenhouse gas emissions -- the number-one threat to the polar bear -- from this successful system. I urge you to take this critically important step in restoring scientific integrity at the Department of Interior by rescinding both of Bush's illegal regulations reducing protections to polar bears. Sarah Bergman, Tucson, AZ James Shannon, Fairfield Bay, AR Keri Dixon, Tucson, AZ Ben Blanding, Lynnwood, WA Bill Haskins, Sacramento, CA Sher Surratt, Middleburg Hts, OH Kassie Siegel, Joshua Tree, CA Sigrid Schraube, Schoeneck Susan Arnot, San Francisco, CA Stephanie Mitchell, Los Angeles, CA Sarah Taylor, NY, NY Simona Bixler, Apo Ae, AE Stephan Flint, Moscow, ID Steve Fardys, Los Angeles, CA Shelbi Kepler, Temecula, CA Kim Crawford, NJ Mary Trujillo, Alhambra, CA Diane Jarosy, Letchworth Garden City,Herts Shari Carpenter, Fallbrook, CA Sheila Kilpatrick, Virginia Beach, VA Kierã¡N Suckling, Tucson, AZ Steve Atkins, Bath Sharon Fleisher, Huntington Station, NY Hans Morgenstern, Miami, FL Shawn Alma, -

MONTY PYTHON at 50 , a Month-Long Season Celebra

Tuesday 16 July 2019, London. The BFI today announces full details of IT’S… MONTY PYTHON AT 50, a month-long season celebrating Monty Python – their roots, influences and subsequent work both as a group, and as individuals. The season, which takes place from 1 September – 1 October at BFI Southbank, forms part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of the beloved comedy group, whose seminal series Monty Python’s Flying Circus first aired on 5th October 1969. The season will include all the Monty Python feature films; oddities and unseen curios from the depths of the BFI National Archive and from Michael Palin’s personal collection of super 8mm films; back-to-back screenings of the entire series of Monty Python’s Flying Circus in a unique big-screen outing; and screenings of post-Python TV (Fawlty Towers, Out of the Trees, Ripping Yarns) and films (Jabberwocky, A Fish Called Wanda, Time Bandits, Wind in the Willows and more). There will also be rare screenings of pre-Python shows At Last the 1948 Show and Do Not Adjust Your Set, both of which will be released on BFI DVD on Monday 16 September, and a free exhibition of Python-related material from the BFI National Archive and The Monty Python Archive, and a Python takeover in the BFI Shop. Reflecting on the legacy and approaching celebrations, the Pythons commented: “Python has survived because we live in an increasingly Pythonesque world. Extreme silliness seems more relevant now than it ever was.” IT’S… MONTY PYTHON AT 50 programmers Justin Johnson and Dick Fiddy said: “We are delighted to share what is undoubtedly one of the most absurd seasons ever presented by the BFI, but even more delighted that it has been put together with help from the Pythons themselves and marked with their golden stamp of silliness. -

{Download PDF} the Monty Pythons Flying Circus: Complete and Annotated: All the Bits

THE MONTY PYTHONS FLYING CIRCUS: COMPLETE AND ANNOTATED: ALL THE BITS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Luke Dempsey | 880 pages | 13 Nov 2012 | Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers Inc | 9781579129132 | English | New York, United States Monty Python's Flying Circus, Season 1 on iTunes It What can I say about the comic genius of Monty Python? I can only offer my homage …. It came out of nowhere. Now my grandmother — MAN. Can you tell me the fastest way there? Uh, Bolton, yes. The M61 through Blackrod, the A or the A Which is fastest? I am not the least bit peckish for fermented curd. Well, then you want to take the M Take this road about 20 kilometers, then take a left at the crossroad. Then take a right and follow it to Khartoum. Are you — are you suggesting I go to Africa? No, no, no — well, yes, yes. Oh yes, fires, and pitchforks and men with horned heads. Horned heads? Oh yes, and nasty sharp, filed teeth and forked tails running about — naked! Are you by chance describing hell? No, no, no — well, yes. I am describing hell. I was just wasting your time. Ah, I see. Can you do me one more favor? Please lay down in front of my car. Whatever you say, squire. Cut to humorous cartoon. Jun 09, Stewart Tame rated it really liked it. This is a huge book. But that's to be expected from a collection of the complete and annotated scripts from all four seasons of Monty Python's Flying Circus. To be honest, the annotations are rather underwhelming. -

American Stage in the Park Bring Outdoors the Musical Comedy, SPAMALOT

For Immediate Release March 30, 2016 Contact: Zachary Hines Audience Development Associate (727) 823-1600 x 209 [email protected] American Stage in the Park Bring Outdoors the Musical Comedy, SPAMALOT. The Wait is Over with Monty Python’s Hilarious Musical opening April 15. St. Petersburg, FL – American Stage in the Park is excited to celebrate over 30 years outdoors with the musical, SPAMALOT which won the 2005 Tony Award for "Best Musical”, the 2005 Drama Desk Award for “Outstanding Musical” and the 2006 Grammy Award for “Best Musical Show Album”. The book and lyrics are by Eric Idle and music by John Du Prez and Eric Idle. The park title sponsor of American Stage in the Park is Bank of America. This outdoor production will be directed by Jonathan Williams and will feature eight lead actors and ten in the chorus. This large cast will feature six familiar faces from previous American Stage productions and twelve new faces to perform on stage in this hilarious musical. SPAMALOT’s Director, Jonathan Williams, is from the San Francisco Bay Area, a graduate of California Institute of the Arts, and co-founder of Capital Stage in Sacramento, CA. Williams said, “I could not be more excited to be directing SPAMALOT for American Stage. The script is such a great homage to Monty Python while standing on its own as a piece of musical theatre. I look forward to helming this project with the support of a great artistic team and a tremendously talented group of actors. I'm really hoping we hit this one out of the park (nudge nudge wink wink).” “SPAMALOT is a perfect fit for the celebratory, fun environment of American Stage in the Park. -

Nobody Expects the Spanish Inquisition

Nobody Expects the Spanish Inquisition Nobody Expects the Spanish Inquisition Cultural Contexts in Monty Python Edited by Tomasz Dobrogoszcz Foreword by Terry Jones ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com 16 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BT, United Kingdom Copyright © 2014 by Rowman & Littlefield All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition : cultural contexts in Monty Python / edited by Tomasz Dobrogoszcz ; foreword by Terry Jones. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-3736-0 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-3737-7 (ebook) 1. Monty Python (Comedy troupe) I. Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, 1970– editor. PN2599.5.T54N63 2014 791.45'028'0922–dc23 2014014377 TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America But remember, if you’ve enjoyed reading this book just half as much as we’ve enjoyed writing it, then we’ve enjoyed it twice as much as you. Contents Acknowledgments ix Foreword xi Part I: Monty Python’s Body and Death 1 1 “It’s a Mr. -

Not Dead Yet: Just Flesh Wounds, Suspensions, and Fines (SEC, CFTC, and FINRA Enforcement Actions in September 2020)

NSCPCurrents OCTOBER 2020 Not Dead Yet: Just Flesh Wounds, Suspensions, and Fines (SEC, CFTC, and FINRA Enforcement Actions in September 2020) By Brian Rubin and Andrea Gordon About the Authors: Brian Rubin is a Partner at Eversheds Sutherland. He can be reached at [email protected]. Andrea Gordon is an Associate at Eversheds Sutherland. She can be reached at [email protected]. 1 OCTOBER 2020 NSCP CURRENTS 1 OCTOBER 2020 NSCP CURRENTS Monty Python, the British comedy troupe, were known for many things, including: • The Ministry of Silly Walks; • Killer Rabbits; • The Lumberjack Song; • Knights Who Say “Ni”; • The Holy Grail; • Wink wink, nudge nudge, say no more; • The Meaning of Life; and • (someone’s favorite title) The Life of Brian1 However, it is less well known that the Pythons also had a lot to say about securities (okay, a little bit to say, but with really cool accents and falsetto voices). Indeed, in one episode, they provided a stock market report: Trading was crisp at the start of the day with some brisk business on the floor. Rubber hardened and string remained confident. Little bits of tin consolidated although biscuits sank after an early gain . Armpits rallied well after a poor start. Small dark furry things increased severely on the floor, whilst rude jellies wobbled up and down, and bounced against rising thighs which had spread to all parts of the country by mid-afternoon. After lunch naughty things dipped sharply forcing giblets upwards with the nicky nacky noo. Ting tang tong rankled dithely, little tipples pooped and poppy things went pong! Gibble gabble gobble went the rickety rackety roo and---2 While the last couple of sentences sound to us (uneducated securities lawyers) a bit like Chaucer, the scene ended abruptly with a bucket of water being poured on the announcer (which should be how many stock market reports and news broadcasts end). -

A Improbabilidade Da Comunicação Em Monty Python

Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras A Improbabilidade da Comunicação em Monty Python André Leonel Ribeiro Duque Gomes Silva Dissertação Mestrado em Cultura e Comunicação 2013 Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras A Improbabilidade da Comunicação em Monty Python André Leonel Ribeiro Duque Gomes Silva Orientação do Prof. Doutor Manuel Frias Martins Dissertação Mestrado em Cultura e Comunicação 2013 Dedicado… Aos meus pais e à minha avó, que me apoiaram desde o início. "Suspense doesn’t have any value unless it’s balanced by humour." Alfred Hitchcock "A vida é demasiado importante para se falar dela a sério." Oscar Wilde Índice Agradecimentos .............................................................................................................. 1 Resumo ............................................................................................................................ 2 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 2 Introdução ....................................................................................................................... 4 Parte I – Humor e comunicação .................................................................................... 8 1. Humor ...................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Definindo conceitos ................................................................................................ 9 1.2 Teorias do -

Fachbereichsarbeit Aus Englisch

Fachbereichsarbeit aus Englisch Verfasserin: Barbara Höllwarth, 8A Betreuungslehrer: Mag. Martin Stehrer Schuljahr: 2002/2003 Erich Fried- Realgymnasium Glasergasse 25, 1090 Wien - 0 - CONTENTS I. It’s… (An Introduction) 2 II. The Early Days 3 III. The Beginning Of An Era 4 IV. Members 1. Graham Chapman 5 2. John Cleese 6 3. Terry Gilliam 8 4. Eric Idle 9 5. Terry Jones 10 8. Michael Palin 11 V. The Closest Anybody's Ever Come To Being A 7th Python 1. Carol Cleveland 12 2. Neil Innes 13 VI. Monty Python’s Flying Circus 1. The Series 14 2. The Beeb 16 3. The German Episodes 17 VII. Films By Monty Python 1. And Now For Something Completely Different 19 2. Monty Python And The Holy Grail 19 3. Life Of Brian 21 4. Monty Python’s The Meaning Of Life 23 VIII. More Films (With/By Python Members) 1. The Rutles – All You Need Is Cash 25 2. A Fish Called Wanda 26 IX. What Monty Python Means To Me 28 - 1 - I. It’s... …actually is the first word in every Episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, announced by an exhausted old man in rags performed by Michael Palin, who, for example, comes out of the sea, crawls out of the desert or falls off a cliff. Sadly, there are still people who ask questions like „What’s Monty Python anyway?“ or even worse “Who is Monty Python?” although there already is a definition of the word “Pythonesque” in the Oxford Dictionary nowadays that says: ”after the style of, or resembling the humour of, Monty Python's Flying Circus, a popular British television comedy series of the 1970s noted esp. -

1966-Pages.Pdf

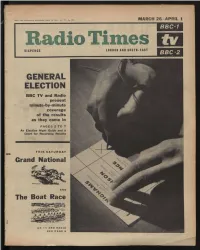

THE GENERAL On Thursday night and Friday morning the BBC both in Television and Radio will be giving you the fastest possible service of Election Results. Here David Butler, one of the expert commentators on tv, explains the background to the broadcasts TELEVISION A Guide for Election Night AND RADIO 1: Terms the commentators use 2: The swing and what it means COVERAGE THERE are 630 constituencies in the United Kingdom in votes and more than 1,600 candidates. The number of seats won by a major is fairly BBC-1 will its one- party begin compre- DEPOSIT Any candidate who fails to secure exactly related to the proportion of the vote which hensive service of results on eighth (12.5%), of the valid votes in his constituency it wins. If the number of seats won by Liberals and soon after of L150. Thursday evening forfeits to the Exchequer a deposit minor parties does not change substantially the close. the polls STRAIGHT FIGHT This term is used when only following table should give a fair guide of how the At the centre of operations two candidates are standing in a constituency. 1966 Parliament will differ from the 1964 Parlia- in the Election studio at ment. (In 1964 Labour won 44.1% of vote and huge MARGINAL SEATS There is no precise definition the TV Centre in London will be 317 seats; Conservatives won 43.4 % of the vote and of a marginal seat. It is a seat where there was a Cliff Michelmore keeping you 304 seats; Liberals 11.2% of the vote and nine seats small majority at the last election or a seat that in touch with all that is �a Labour majority over all of going is to change hands. -

Monty Python's Completely Useless Web Site

Home Get Files From: ● MP's Flying Circus ● Completely Diff. ● Holy Grail ● Life of Brian ● Hollywood Bowl ● Meaning of Life General Information | Monty Python's Flying Circus | Monty Python and the Holy Grail | Monty Python's Life of Brian | Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl | Monty Python's The Meaning of Life | Monty Python's Songs | Monty Python's Albums | Monty Python's ...or jump right to: Books ● Pictures ● Sounds ● Video General Information ● Scripts ● The Monty Python FAQ (25 Kb) Other stuff: ● Monty Python Store ● Forums RETURN TO TOP ● About Monty Python's Flying Circus Search Now: ● Episode Guide (18 Kb) ● The Man Who Speaks In Anagrams ● The Architects ● Argument Sketch ● Banter Sketch ● Bicycle Repair Man ● Buying a Bed ● Blackmail ● Dead Bishop ● The Man With Three Buttocks ● Burying The Cat ● The Cheese Shoppe ● Interview With Sir Edward Ross ● The Cycling Tour (42 Kb) ● Dennis Moore ● The Hairdressers' Ascent up Mount Everest ● Self-defense Against Fresh Fruit ● The Hospital ● Johann Gambolputty... ● The Lumberjack Song [SONG] ● The North Minehead Bye-Election ● The Money Programme ● The Money Song [SONG] ● The News For Parrots ● Penguin On The Television ● The Hungarian Phrasebook ● Flying Sheep ● The Pet Shop ● The Tale Of The Piranha Brothers (10 Kb) ● String ● A Pet Shop Near Melton Mowbray ● The Trail ● Arthur 'Two Sheds' Jackson ● The Woody Sketch ● 1972 German Special (42 Kb) RETURN TO TOP Monty Python and the Holy Grail ● Complete Script Version 1 (74 Kb) ● Complete Script Version 2 (195 Kb) ● The Album Of