One Helluva Roar: US Air Force Public Communication Since 1942

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biography U N I T E D S T a T E S a I R F O R C E

BIOGRAPHY U N I T E D S T A T E S A I R F O R C E LIEUTENANT GENERAL TIMOTHY D. HAUGH Lt. Gen. Timothy D. Haugh is the Commander, Sixteenth Air Force; Commander, Air Forces Cyber, and Commander, Joint Force Headquarters-Cyber, Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, Texas. General Haugh is responsible for more than 44,000 personnel conducting worldwide operations. Sixteenth Air Force Airmen deliver multisource intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance products, applications, capabilities and resources. In addition, they build, extend, operate, secure and defend the Air Force portion of the Department of Defense global network. Furthermore, Joint Forces Headquarters-Cyber personnel perform operational planning as part of coordinated efforts to support Air Force component and combatant commanders and, upon approval of the President and/or Secretary of Defense, the execution of offensive cyberspace operations. In his position as Sixteenth Air Force Commander, General Haugh also serves as the Commander of the Service Cryptologic Component. In this capacity, he is responsible to the Director, National Security Agency, and Chief, Central Security Service, as the Air Force’s sole authority for matters involving the conduct of cryptologic activities, including the spectrum of missions related to tactical warfighting and national-level operations. The general leads the global information warfare activities spanning cyberspace operations, intelligence, targeting, and weather for nine wings, one technical center, and an operations center. General Haugh received his commission in 1991, as a distinguished graduate of the ROTC program at Lehigh University. He has served in a variety of intelligence and cyber command and staff assignments. -

The Siege of Przemysl 1914–1915

The Siege of Przemysl´ 1914–1915 by Dr. Jerzy W. Kupiec-Weglinski the outbreak of World War I, Przemyśl was a small garri- son town of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the territory At of Polish Galicia between two provincial capitals, Krakow (Cracow) in the west and Lwow (Lemberg) in the east.1 Just forty miles from the frontier with Imperial Russia, Przemyśl was pro- tected by a ring of fortifications thirty-six miles in circumference, similar to the French Maginot Line. After Austria declared war on Russia on August 6, 1914, the Third Russian Army of Radko- Dimitriev advanced on Przemyśl, and by September 18 the for- tress was completely besieged. Luckily, the blockade was quickly relieved, lasting only thirty-three days. However, the Russians soon returned, and the second siege commenced on November 10. One hundred and thirty-three days later on March 22, 1915, after disease and starvation had taken their toll, Commander General Hermann von Kusmanek, nine generals, ninety-three staff officers, 2,500 officers, and 117,900 men all surrendered to the Russians. In all, some 12,000 defenders and 100,000 Russians perished in Przemyśl, which makes it one of the largest and bloodiest sieges in the world’s military history. The provisional air mail effort set up in the besieged Przemyśl by the Austrian Army represents an important chapter in the his- tory of aerophilately. The desperate necessity of the Przemyśl de- fendants to communicate with the outside world, especially with loved ones, was the primary reason for establishing such a service. This venture, unlike many others that followed, was never phila- telically motivated. -

Military and Diplomatic Mail Service. Report Number MS-AR-19-003

Cover Office of Inspector General | United States Postal Service Audit Report Military and Diplomatic Mail Service Report Number MS-AR-19-003 | July 31, 2019 Table of Contents Cover Highlights........................................................................................................................................................... 1 Objective ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 What the OIG Found ................................................................................................................................ 1 What the OIG Recommended ............................................................................................................. 2 Transmittal Letter .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Results................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction/Objective ........................................................................................................................... 4 Background .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Finding #1: Military and Diplomatic Mail Service ....................................................................... -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

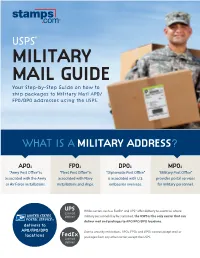

Your Step-By-Step Guide on How to Ship Packages to Military Mail APO/ FPO/DPO Addresses Using the USPS

USPS® MILITARY MAIL GUIDE Your Step-by-Step Guide on how to ship packages to Military Mail APO/ FPO/DPO addresses using the USPS. WHAT IS A MILITARY ADDRESS? APO: FPO: DPO: MPO: “Army Post Office” is “Fleet Post Office” is “Diplomatic Post Office” “Military Post Office” associated with the Army associated with Navy is associated with U.S. provides postal services or Air Force installations. installations and ships. embassies overseas. for military personnel. UPS While carriers such as FedEx® and UPS® offer delivery to countries where cannot deliver military personnel may be stationed, the USPS is the only carrier that can deliver mail and packages to APO/FPO/DPO locations. delivers to APO/FPO/DPO Due to security restrictions, APOs, FPOs and DPOs cannot accept mail or locations FedEx cannot packages from any other carrier, except the USPS. deliver HOW TO ADDRESS A SHIPPING LABEL FOR AN APO/FPO/DPO PACKAGE 2 INCLUDE THE UNIT AND BOX NUMBER Army: Unit [Number] Box [Number] Air Force: PSC* [Number] Box [Number] 1 NAME OF THE RECIPIENT Rank/grade/rating is optional Navy: Ship [Number] Hull [Number] for APO or FPO. Do not include 5 ZIP CODE recipient’s title for DPO. Embassy: Unit [Number] Box [Number] 3 CITY 4 STATE APO, FPO or DPO AA (Armed Forces Americas) AE (Armed Forces Europe) AP (Armed Forces Pacific) 1 Enter the full name of the addressee. Mail addressed to ‘Any Service Member’ or similar wording such as ‘Any CORRECT FORMAT WRONG FORMAT Soldier, Sailor, Airman or Marine’ is prohibited. Mail must CPT John Doe CPT John Doe be addressed to an individual name or job title, such as Unit 45013 Box 2666 USAG J Box 2666 ‘Sergeant’ or ‘Private First Class.’ USAG J APO AP 96338 APO AP 96338 2 Enter the unit or Post Office box number. -

Technology Innovation and the Future of Air Force Intelligence Analysis

C O R P O R A T I O N LANCE MENTHE, DAHLIA ANNE GOLDFELD, ABBIE TINGSTAD, SHERRILL LINGEL, EDWARD GEIST, DONALD BRUNK, AMANDA WICKER, SARAH SOLIMAN, BALYS GINTAUTAS, ANNE STICKELLS, AMADO CORDOVA Technology Innovation and the Future of Air Force Intelligence Analysis Volume 2, Technical Analysis and Supporting Material RR-A341-2_cover.indd All Pages 2/8/21 12:20 PM For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA341-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0633-0 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. William Chockey; faraktinov, Adobe Stock. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. -

4407.Pdf (6740 Кбайт)

Deliberate Force A Case Study in Effective Air Campaigning Final Report of the Air University Balkans Air Campaign Study Edited by Col Robert C. Owen, USAF Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama January 2000 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Deliberate force a case study in effective air campaigning : final report of the Air University Balkans air campaign study / edited by Robert C. Owen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-076-0 1. Yugoslav War, 1991–1995—Aerial operations. 2. Yugoslav War, 1991– 1995—Campaigns—Bosnia and Hercegovina. 3. Yugoslav War, 1991–1995—Foreign participation. 4. Peacekeeping forces—Bosnia and Hercegovina. 5. North Atlantic Treaty Organization—Armed Forces—Aviation. 6. Bosnia and Hercegovina— History, Military. I. Owen, Robert C., 1951– DR1313.7.A47 D45 2000 949.703—dc21 99-087096 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . xi ABOUT THE EDITOR . xv PREFACE . xvii 1 The Demise of Yugoslavia and the Destruction of Bosnia: Strategic Causes, Effects, and Responses . 1 Dr. Karl Mueller 2 The Planning Background . 37 Lt Col Bradley S. Davis 3 US and NATO Doctrine for Campaign Planning . 65 Col Maris McCrabb 4 The Deliberate Force Air Campaign Plan . 87 Col Christopher M. Campbell 5 Executing Deliberate Force, 30 August–14 September 1995 . 131 Lt Col Mark J. -

MILITARY MAIL: FAQ MILITARY POSTAL SERVICE AGENCY A: No

Q: When addressing mail to a Military Post Office™ (MPO), should I also use the city and country name? MILITARY MAIL: FAQ MILITARY POSTAL SERVICE AGENCY A: No. Always use the APO or FPO address, http://hqdainet.army.mil/mpsa without the name of the city and country. This is to make sure the item is handled in the military mail system instead of the international mail system. INCORRECT: CORRECT: PFC John Doe PFC John Doe 123rd ENG 2nd PLT - B CO 123rd ENG 2nd PLT - B CO APO AE 09398-9998 APO AE 09398-9998 BAGHDAD, IRAQ Q: What is the difference between Parcel Post® and Priority Mail® articles mailed to an MPO? A: In most cases Parcel Post® articles weighing more than 15 pounds or measuring more than 60 inches (length and girth combined) will travel by ship from the U.S. gateway to the military address. Priority Mail® articles receive air transportation from the U.S. gateway to the location of the military address overseas. Q: Are extra services such as Insured Mail, Registered Mail™, and Delivery Confirmation™ services available for military mail? A: Yes. In general, articles mailed to MPOs are eligible for extra services; but extra services may not be available to all MPOs. For more information consult a USPS® retail associate or the USPS Web Site at www.usps.com. Q: Can I track a package addressed to an APO / FPO location with the customs declaration form number? A: No — customs declaration numbers are used to track only international mail articles. To track an APO / FPO item, you must purchase an applicable extra service. -

DMM Advisory

August 13, 2020 DMM Advisory Keeping you informed about classification and mailing standards of the United States Postal Service International Service Impacts – Country Suspensions as of August 14, 2020 Effective August 14, 2020, the Postal Service will temporarily suspend international mail acceptance to destinations where transportation is unavailable due to widespread cancellations and restrictions into the area. Customers are asked to refrain from mailing items addressed to the following country, until further notice: • Syria This service disruption affects Priority Mail Express International® (PMEI), Priority Mail International® (PMI), First-Class Mail International® (FCMI), First-Class Package International Service® (FCPIS®), International Priority Airmail® (IPA®), International Surface Air Lift® (ISAL®), and M-Bag® items. Unless otherwise noted, service suspensions to a particular country do not affect delivery of military and diplomatic mail. For already deposited items, other than Global Express Guarantee® (GXG®), Postal Service International Service Center (ISC) employees will endorse the items as “Mail Service Suspended — Return to Sender” and then place them in the mail stream for return. Due to COVID-19, international shipping has been suspended to many countries. According to DMM 604.9.2.3, customers are entitled to a full refund of their postage costs when service to the country of destination is suspended. The detailed procedures to obtain refunds for Retail Postage, eVS, PC Postage, and BMEU entered mail can be found through -

Report of F-16 Accident Which Occurred on 01/26/95

4+49 6565 617416 05 JUN ?5 09:14 T F :CA 452-7416 "~1 DOCKETED USNRC PEl? 2003 JAN 17 PH' 1: 49 OFFICE fIF (ýe SGECFIVARY RULEIIAKiNGS AND ADJUDICATIONS STAFF AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION REPORT F-16CG, SN 89-2036 AVIANO AIR BASE, ITALY WILLIAM F. RAKE. Lieutenant Colonel. USAF Accident Investigation Officer JAMES D. STEVENS, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Legal Advisor RICHARD (NMI) PEEPLES, Senior Master Sergeant, USAF Technical Advisor NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION Docket No -- Official Exh. No In the matter of S"Iff IDENTIFIED A.21:i a nt _ RECEIVED Iv. ýnr REJECTED "Off'r____ ____ F-& C rl•:tor _DATE _ ___ F 1-76 58070 I _ _ -__. Witness Reporter U_________________ 7_ecobp/a7e 5C c Y-O .5e6-rj- en) +49 6565 617416 05 JUJ '935 09:14 T:' F 'CA -52-7416 P.3/17 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Statement of Authonty 5 Statement of Purpose 5 Summary of Facts 6 History of Flight 6 Mission 6 Briefing and Preflight 7 Flight Activity 8 Impact 9 Egress System 9 Personal and Survivai Equipment 9 Rescue and Crash Recovery 9 Maintenance Documentation 10 Maintenance Personnel and Supervision 14 Engine, Fuei, Hydraulic, and Oil Inspection Analysis 11 Airframe and Aircraft Systems 11 Operatons Personnei and Supervision 12 Pilot Qualifications 12 Medical 13 NAVAIDS. Facilities. and NOTAMs 13 Weather , 13 Governing Directives and Publications 13 Statement of Opinion 15 Certification 2 58071 +49 6565 617416 05 JUN '95? 09:14 5C F :CA 452-7416 P.4/17 Legal Sufficiency Review 17 Glossary of Terms 18 SAFETY INVESTIGATION BOARD, PART I Tab AF Form 711, USAF Mishap Report A AF Form 71, 1 b, Aircraft Flight Mishap Report C AF Form 71 1c, Aircraft Maintenance and Materiel Report D Flight and Personnel Records G AFTO Forms 781. -

U.S. Military Bases and Facilities in the Middle East

U.S. Military Bases and Facilities in the Middle East Fact Sheet - Matthew Wallin i June 2018 BOARD OF DIRECTORS The Honorable Gary Hart, Chairman Emeritus Admiral William Fallon, USN (Ret.) Senator Hart served the State of Colorado in the U.S. Senate Admiral Fallon has led U.S. and Allied forces and played a and was a member of the Committee on Armed Services leadership role in military and diplomatic matters at the highest during his tenure. levels of the U.S. government. Governor Christine Todd Whitman, Chairperson Raj Fernando Christine Todd Whitman is the President of the Whitman Strategy Group, a consulting firm that specializes in energy Raj Fernando is CEO and founder of Chopper Trading, a and environmental issues. technology based trading firm headquartered in Chicago. Nelson W. Cunningham, President of ASP Nelson Cunningham is President of McLarty Associates, the Scott Gilbert international strategic advisory firm headed by former White Scott Gilbert is a Partner of Gilbert LLP and Managing House Chief of Staff and Special Envoy for the Americas Director of Reneo LLC. Thomas F. “Mack” McLarty, III. Brigadier General Stephen A. Cheney, USMC (Ret.) Vice Admiral Lee Gunn, USN (Ret.) Brigadier General Cheney is the Chief Executive Officer of Vice Admiral Gunn is the President of the Institute of Public ASP. Research at the CNA Corporation, a non-profit corporation in Virginia. Norman R. Augustine The Honorable Chuck Hagel Mr. Augustine was Chairman and Principal Officer of the Chuck Hagel served as the 24th U.S. Secretary of Defense and American Red Cross for nine years and Chairman of the served two terms in the United States Senate (1997-2009).