Guiding Principles & Illustrated Examples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advancements in Arch Analysis and Design During the Age of Enlightenment

ADVANCEMENTS IN ARCH ANALYSIS AND DESIGN DURING THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT by EMILY GARRISON B.S., Kansas State University, 2016 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Architectural Engineering and Construction Science and Management College of Engineering KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Approved by: Major Professor Kimberly Waggle Kramer, PE, SE Copyright Emily Garrison 2016. Abstract Prior to the Age of Enlightenment, arches were designed by empirical rules based off of previous successes or failures. The Age of Enlightenment brought about the emergence of statics and mechanics, which scholars promptly applied to masonry arch analysis and design. Masonry was assumed to be infinitely strong, so the scholars concerned themselves mainly with arch stability. Early Age of Enlightenment scholars defined the path of the compression force in the arch, or the shape of the true arch, as a catenary, while most scholars studying arches used statics with some mechanics to idealize the behavior of arches. These scholars can be broken into two categories, those who neglected friction and those who included it. The scholars of the first half of the 18th century understood the presence of friction, but it was not able to be quantified until the second half of the century. The advancements made during the Age of Enlightenment were the foundation for structural engineering as it is known today. The statics and mechanics used by the 17th and 18th century scholars are the same used by structural engineers today with changes only in the assumptions made in order to idealize an arch. -

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof. Wang, Yaohua Fujian Normal University, China Intangible cultural heritage is the memory of human historical culture, the root of human culture, the ‘energic origin’ of the spirit of human culture and the footstone for the construction of modern human civilization. Ever since China joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004, it has done a lot not only on cognition but also on action to contribute to the protection and transmission of intangible cultural heritage. Please allow me to expatiate these on the case of Chinese nanyin(南音, southern music). I. The precious multi-values of nanyin decide the necessity of protection and transmission for Chinese nanyin. Nanyin, also known as “nanqu” (南曲), “nanyue” (南乐), “nanguan” (南管), “xianguan” (弦管), is one of the oldest music genres with strong local characteristics. As major musical genre, it prevails in the south of Fujian – both in the cities and countryside of Quanzhou, Xiamen, Zhangzhou – and is also quite popular in Taiwan, Hongkong, Macao and the countries of Southeast Asia inhabited by Chinese immigrants from South Fujian. The music of nanyin is also found in various Fujian local operas such as Liyuan Opera (梨园戏), Gaojia Opera (高甲戏), line-leading puppet show (提线木偶戏), Dacheng Opera (打城戏) and the like, forming an essential part of their vocal melodies and instrumental music. As the intangible cultural heritage, nanyin has such values as follows. I.I. Academic value and historical value Nanyin enjoys a reputation as “a living fossil of the ancient music”, as we can trace its relevance to and inheritance of Chinese ancient music in terms of their musical phenomena and features of musical form. -

Secret in the Stone

Also by Kamilla Benko The Unicorn Quest WPS: Prepress/Printer’s Proof 9781408898512_txt_print.pdf November 15, 2018 13:06:25 WPS: Prepress/Printer’s Proof 9781408898512_txt_print.pdf November 15, 2018 13:06:25 “WAR CHANT” Axes chop And hammers swing, Soldiers stomp, But diamonds gleam. Mothers weep And fathers worry, But only war Can bring me glory. Emeralds shine And rubies mourn, But there’s no mine For unicorn’s horn. Axes chop And hammers swing, My heart stops, But war cries ring. Gemmer Army Marching Chant Lyrics circa 990 Craft Era Composer unknown CHAPTER 1 Graveyard. That was the first word that came to Claire Martinson’s mind as she took in the ruined city ahead of her. The second and third words were: Absolutely not. There was no way this could be the city they’d been seeking—the Gem- mer school where Claire would learn how to perfect her magic. Where she was going to figure out how to bring unicorns back to Arden. This was . “A ghost town,” Claire whispered. “Are you sure it’s Stonehaven?” Sophie asked, and Claire was glad to hear some apprehension in her older sister’s voice. If Sophie, who at the age of thirteen had already explored a magical land by herself, defeated a mysterious illness, and passed sixth grade, wasn’t feeling great about their final desti- nation, then maybe Claire wasn’t such a coward after all. “It looks so . .” “Creepy?” Claire offered. Sophie tightened the ribbon on her ponytail. “Desolate,” she finished. Desolate, indeed. Stone houses stood abandoned, their win- dows as empty as the sockets of a skull. -

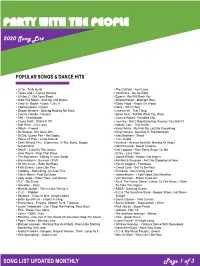

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

The Story of Architecture

A/ft CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FINE ARTS LIBRARY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 062 545 193 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1992. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924062545193 o o I I < y 5 o < A. O u < 3 w s H > ua: S O Q J H HE STORY OF ARCHITECTURE: AN OUTLINE OF THE STYLES IN T ALL COUNTRIES • « « * BY CHARLES THOMPSON MATHEWS, M. A. FELLOW OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS AUTHOR OF THE RENAISSANCE UNDER THE VALOIS NEW YORK D. APPLETON AND COMPANY 1896 Copyright, 1896, By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY. INTRODUCTORY. Architecture, like philosophy, dates from the morning of the mind's history. Primitive man found Nature beautiful to look at, wet and uncomfortable to live in; a shelter became the first desideratum; and hence arose " the most useful of the fine arts, and the finest of the useful arts." Its history, however, does not begin until the thought of beauty had insinuated itself into the mind of the builder. -

4.7 the Sword in the Stone

4.7 The Sword in the Stone (King Arthur, famous in legends and history as one of the bravest and noblest Kings of Britain, grew up as an orphaned youth, before Destiny intervened, in the form of his protector and guardian, Merlin the Magician, to reveal his true identity to the people of Britain.) In ancient Britain, at a time when the land was invaded by wild barbarians, the good and noble Lord Uther fought them bravely and drove them away from his land. The people made him king of Britain and gave him the title, Pendragon, meaning Dragon’s head. King Uther Pendragon ruled Britain wisely and well; the people were content. But very soon, the king died; it was thought that he had been poisoned by some traitors. There was no heir to the throne of British. The powerful Lords and Knights who had been kept under control by King Uther, now began to demand that one of them should be crowned King of Britain. Rivalry grew amongst the Lords, and the country as a whole began to suffer. Armed robbers roamed the countryside, pillaging farms and fields. People felt unsafe and insecure in their own homes. Fear gripped the country and lawlessness prevailed over the divided kingdom. Nearly sixteen years had passed since the death of Lord Uther. All the Lords and Knights of Britain had assembled at the Great Church of London for Christmas. On Christmas morning, just as they were leaving the Church, a strange sight drew their attention. In the churchyard was a large stone, and on it an anvil of steel, and in the steel a naked sword was held, and about it was written in letters of gold, ‘Whoso pulleth out this sword is by right of birth King of England.’ Many of the knights could not hold themselves back. -

Stone Mountain State Park

OUR CHANGING LAND Stone Mountain State Park An Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for Grades 4-8 “The face of places, and their forms decay; And what is solid earth, that once was sea; Seas, in their turn, retreating from the shore, Make solid land, what ocean was before.” - Ovid Metamorphoses, XV “The earth is not finished, but is now being, and will forevermore be remade.” - C.R. Van Hise Renowned geologist, 1898 i Funding for the second edition of this Environmental Education Learning Experience was contributed by: N.C. Division of Land Resources, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and the N.C. Mining Commission ii This Environmental Education Learning Experience was developed by Larry Trivette Lead Interpretation and Education Ranger Stone Mountain State Park; and Lea J. Beazley, Interpretation and Education Specialist North Carolina State Parks N.C. Division of Parks and Recreation Department of Environment and Natural Resources Michael F. Easley William G. Ross, Jr. Governor Secretary iii Other Contributors . Park volunteers; Carl Merschat, Mark Carter and Tyler Clark, N.C. Geological Survey, Division of Land Resources; Tracy Davis, N.C. Division of Land Resources; The N.C. Department of Public Instruction; The N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources; and the many individuals and agencies who assisted in the review of this publication. 385 copies of this public document were printed at a cost of $2,483.25 or $6.45 per copy Printed on recycled paper. 10-02 iv Table of Contents 1. Introduction • Introduction to the North Carolina State Parks System.......................................... 1.1 • Introduction to Stone Mountain State Park ........................................................... -

Acta SLIKE Za INTERNET.Pmd

ACTA CARSOLOGICA 32/2 13 161-174 LJUBLJANA 2003 COBISS: 1.01 LANDUSE AND LAND COVER CHANGE IN THE LUNAN STONE FOREST, CHINA UPORABA POVRŠJA IN SPREMEMBE RASTLINSKEGA POKROVA V LUNANSKEM KAMNITEM GOZDU, KITAJSKA CHUANRONG ZHANG & MICHAEL DAY & WEIDONG LI 1 Department of Geography, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53201, USA. E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Prejeto / received: 4. 7. 2003 161 Acta carsologica, 32/2 (2003) Abstract UDC: 551.44:504.03(510) Chuanrong Zhang & Michael Day & Weidong Li: Landuse and Land Cover Change in the Lunan Stone Forest, China The Lunan Stone Forest is the World’s premier pinnacle karst landscape, with attendant scientific and cultural importance. Ecologically fragile, it is also a major tourist attraction, currently receiving over 1.5million visitors each year. Conservation efforts have been undermined by conflicting economic priorities, and landscape degradation threatens the very foundation of the national park. Assessment of the current land cover in the 35km2 core of the Stone Forest and an analysis of land cover change since 1974 in the 7km2 Major Stone Forest reveal the extent of recent landscape change. Exposed pinnacle karst covers 52% of the 35km2 study area, and about half of this is vegetated. Land use is dominated by agriculture, particularly in the valleys, but much of the shilin is devegetated and about six percent of the area is now built-up. Within the 7km2 Major Stone Forest the built-up area increased from 0.15ha in 1974 to 38.68ha by 2001, and during that same period road length increased by 95%, accompanied by a 3% decrease in surface water area. -

Hana Taragan HISTORICAL REFERENCE in MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE: BAYBARS's BUILDINGS in PALESTINE

the israeli academic center in cairo ¯È‰˜· Èχ¯˘È‰ ÈÓ„˜‡‰ ÊίӉ Hana Taragan HISTORICAL REFERENCE IN MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE: BAYBARS’S BUILDINGS IN PALESTINE Hana Taragan is a lecturer in Islamic art at Tel Aviv University, where she received her Ph.D. in 1992. Her current research concerns Umayyad and Mamluk architecture in Eretz Israel in the medieval period. She is the author of Art and Patronage in the Umayyad Palace in Jericho (in Hebrew) and of numerous articles in the field of Islamic art. In the year 1274, al-Malik al-Zahir also changed a structure’s function Baybars, the first Mamluk ruler of from church to mosque, as he did Palestine (1260–1277), ordered the in Qaqun.5 addition of a riwaq (porch) to the Baybars’s choice of Yavne may tomb of Abu Hurayra in Yavne.1 be explained by the ruin of the The riwaq, featuring a tripartite coastal towns, or by Yavne’s loca- portal and six tiny domes, had two tion on the main road from Cairo arches decorated with cushion to Damascus. However, it seems to voussoirs and one with a zigzag me that above and beyond any frieze (Figure 1). Baybars also strategic and administrative con- installed a dedicatory inscription siderations, Baybars focused on naming himself as builder of the this site in an attempt to exploit riwaq.2 The addition of a portal to Abu Hurayra’s tomb as a means of the existing tomb structure typifies institutionalizing the power of the Baybars’s building policy in Pales- Mamluk dynasty in general and tine. -

Repertoire Step The

Repertoire Step the Gap Valerie Amy Winehouse Think Aretha Franklin Seven Nation Army Ben L’oncle Soul Shake Your Tailfeather Blues Brothers Soul Man Blues Brothers Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Good Times Chic Relight My Fire Dan Hartman Smoorverliefd Doe Maar Hot Stuff Donna Summer Long Train Running Doobie Brothers Boogie Nights Earth Wind and Fire Getaway Earth Wind and Fire I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor Proud Mary Ike & Tina Turner Blame It on the Boogie Jackson 5 I Want You Back Jackson 5 Rock With You Michael Jackson Lady Marmalade Patti LaBelle I’m So Excited Pointer Sisters, The I Wish Stevie Wonder Signed Sealed Delivered Stevie Wonder Sir Duke Stevie Wonder Soul With a Capital S Tower of Power Disco Inferno Trammps I Wanna Dance With Somebody Whitney Houston Play That Funky Music Wild Cherry Kool Brothers and Sisters Medley Stomp! Brothers Johnson Celebration Kool and the Gang Get Down On It Kool and the Gang Ladies Night Kool and the Gang Straight Ahead Kool and the Gang He’s The Greatest Dancer Sister Sledge Lost In Music Sister Sledge Getting Jiggy With It Will Smith Michael Jackson Medley Can You Feel It Jackson 5 Shake Your Body Jackson 5 Billie Jean Michael Jackson Black or White Michael Jackson Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough Michael Jackson Love Never Felt So Good Michael Jackson Thriller Michael Jackson Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ Michael Jackson Workin’ Day and Night Michael Jackson Short Disco Medley Candi Station Young Hearts, Run Free Cheryl Lynn Got To Be Real Diana Ross I’m Coming Out George Benson Gimme the Night Luther Vandross Never Too Much McFadden, Whitehead Ain’t No Stopping Us Now Foute Medley Ring My Bell Anita Ward Yes Sir, I Can Boogie Baccara Rasputin Boney M. -

Historic Stone Highway Culverts in New Hampshire Asset Management Manual

Historic Stone Highway Culverts in New Hampshire Asset Management Manual Prepared for: New Hampshire Department of Transportation, Bureau of Environment, Concord. Prepared by: Historic Documentation Company, Inc., Portsmouth, RI September 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose......................................................................................................................1 1.2 Why Preserve Historic Stone Culverts .....................................................................2 2.0 IDENTIFYING HISTORIC STONE CULVERTS.......................................................4 2.1 General Information .................................................................................................4 2.2 New Hampshire Stone Culverts................................................................................7 2.3 Stone Box Culverts ...................................................................................................8 2.4 Stone Arch Culverts................................................................................................14 3.0 MAINTAINING HISTORIC STONE CULVERTS ..................................................16 3.1 General Maintenance Discussion ...........................................................................16 3.2 Inspection & Maintenance Program ......................................................................17 3.3 Clear Waterway .....................................................................................................18 -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos.