Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Knowledge

Intellectual Property and Traditional Knowledge The current international system for protecting intellectual property was fashioned during the age of industrialization and developed subsequently in line with the perceived needs of technologically advanced societies. However, in recent years, indigenous peoples, local communities, and governments mainly in developing countries, have demanded equivalent protection for traditional knowledge . WIPO member states take part in negotiations within the Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC), in order to develop an international legal instrument (or instruments) that would give traditional knowledge, genetic resources and traditional cultural expressions (folklore) effective and balanced protection. Such an instrument could range from a recommendation to WIPO members to a formal treaty that would bind countries choosing to ratify it. Representatives of indigenous and local communities are assisted by the WIPO Voluntary Fund to attend the IGC, and their active participation is crucial for a successful outcome. Traditional knowledge is not so-called because of its antiquity, much traditional knowledge and many traditional cultural expressions are not ancient or inert, but a vital, dynamic part of the lives of many communities today. The adjective “traditional” qualifies a form of knowledge or an expression which has a traditional link with a community: it is developed, sustained and passed on within a community, sometimes through specific customary systems of transmission. In short, it is the relationship with the community that makes knowledge or expressions “traditional.” Traditional knowledge is not easily protected by the current intellectual property system, which typically grants protection for a limited period to inventions and original works by named individuals or companies. -

Indigenous Experiences in the U.S. with Climate Change

Climate Change and Environmental StewardshipIndigenous Experiences in the Anthropocene in the U.S. with Abstract: The recognition of climate change issues facing trib- al communities and indigenous peoples in the United States Karletta Chief is growing, and understanding its impacts is rooted in indig- (Navajo Nation), Assistant enous ethical perspectives and systems of ecological knowl- Professor, Department of Soil, edge. This foundation presents a context and guide for con- Water, and Environmental temporary indigenous approaches to address climate change Sciences, University of impacts that are comprehensive and holistic. Tribal communi- Arizona, Tucson, AZ ties and indigenous peoples across the United States are re- envisioning the role of science in the Anthropocene; working John J. Daigle to strengthen government-to-government relationships in cli- mate change initiatives; and leading climate change research, (Penobscot Nation), Associate mitigation and adaptation plans through indigenous ingenuity. Professor, School of Forest Unique adaptive capacities of tribal communities stem from Resources, University of their ethics and knowledge, and help frame and guide suc- Maine, Orono, ME cessful adaptation. As documented in the Special Issue of the Climatic Change Journal on the impacts of climate change to Kathy Lynn U.S. indigenous communities (Maldonado and others 2013), these issues include the loss of traditional knowledge; impacts Adjunct Faculty Researcher, to forests, ecosystems, traditional foods, and water; thawing Environmental Studies of Arctic sea ice and permafrost; and relocation of communi- Program, University of ties. This collaboration, by more than 50 authors from tribal Oregon, Eugene, OR communities, academia, government agencies, and NGOs, demonstrates the increasing awareness, interest, and need to Kyle Powys Whyte understand the unique ways in which climate change will af- (Citizen Potawatomi fect tribal cultures, lands, and traditional ways of life. -

Using Modern Technologies to Capture and Share Indigenous Astronomical Knowledge

Australian Academic & Research Libraries (2014) | Preprint Using Modern Technologies to Capture and Share Indigenous Astronomical Knowledge Martin Nakata a*, Duane Hamacher a, John Warren e, Alex Byrned, Maurice Pagnucco b, Ross Harley c, Srikumar Venugopal b, Kirsten Thorpe d, Richard Neville d and Reuben Bolt a a Nura Gili Indigenous Programs Unit, University of New South Wales b School of Computer Science and Engineering, University of New South Wales c College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney d State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia e Microsoft Research, North Ryde, Australia Abstract Indigenous Knowledge is important for Indigenous communities across the globe and for the advancement of our general scientific knowledge. In particular, Indigenous astronomical knowledge integrates many aspects of Indigenous Knowledge, including seasonal calendars, navigation, food economics, law, ceremony, and social structure. We aim to develop innovative ways of capturing, managing, and disseminating Indigenous astronomical knowledge for Indigenous communities and the general public for the future. Capturing, managing, and disseminating this knowledge in the digital environment poses a number of challenges, which we aim to address using a collaborative project involving experts in the higher education, library, and industry sectors. Using Microsoft’s WorldWide Telescope and Rich Interactive Narratives technologies, we propose to develop software, media design, and archival management solutions to allow Indigenous communities to share their astronomical knowledge with the world on their terms and in a culturally sensitive manner. Keywords: Indigenous Knowledge, cultural astronomy, data management, Intellectual property, Indigenous Australians. Introduction Although increasing numbers of Indigenous people live less traditional lives, many still seek to maintain meaningful connections to their traditional knowledge, heritage, and land (Edwards and Heinrich 2006). -

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof. Wang, Yaohua Fujian Normal University, China Intangible cultural heritage is the memory of human historical culture, the root of human culture, the ‘energic origin’ of the spirit of human culture and the footstone for the construction of modern human civilization. Ever since China joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004, it has done a lot not only on cognition but also on action to contribute to the protection and transmission of intangible cultural heritage. Please allow me to expatiate these on the case of Chinese nanyin(南音, southern music). I. The precious multi-values of nanyin decide the necessity of protection and transmission for Chinese nanyin. Nanyin, also known as “nanqu” (南曲), “nanyue” (南乐), “nanguan” (南管), “xianguan” (弦管), is one of the oldest music genres with strong local characteristics. As major musical genre, it prevails in the south of Fujian – both in the cities and countryside of Quanzhou, Xiamen, Zhangzhou – and is also quite popular in Taiwan, Hongkong, Macao and the countries of Southeast Asia inhabited by Chinese immigrants from South Fujian. The music of nanyin is also found in various Fujian local operas such as Liyuan Opera (梨园戏), Gaojia Opera (高甲戏), line-leading puppet show (提线木偶戏), Dacheng Opera (打城戏) and the like, forming an essential part of their vocal melodies and instrumental music. As the intangible cultural heritage, nanyin has such values as follows. I.I. Academic value and historical value Nanyin enjoys a reputation as “a living fossil of the ancient music”, as we can trace its relevance to and inheritance of Chinese ancient music in terms of their musical phenomena and features of musical form. -

Traditional Knowledge and Global Lawmaking Kuei-Jung Ni

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 10 | Issue 2 Article 3 Winter 2011 Traditional Knowledge and Global Lawmaking Kuei-Jung Ni Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Kuei-Jung Ni, Traditional Knowledge and Global Lawmaking, 10 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 85 (2011). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol10/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Vol. 10:2] Kuei-Jung Ni Traditional Knowledge and Global Lawmaking Kuei-Jung Ni! I. INTRODUCTION ¶1 The value and significance of traditional knowledge (TK)1 has been widely recognized. According to the study of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), TK has tremendous merits in various respects, generating cultural, social, ecological, biological, agricultural, and industrial values.2 ¶2 In short, TK refers to the knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities in the world. Yet there seems to be no definite and universally approved definition of TK.3 The concept of TK may be reflected in the work of the WIPO, which outlines its general scope as follows: [T]he term “traditional knowledge” refers to the content or substance of knowledge resulting from intellectual activity in a traditional context, and includes the know-how, skills, innovations, practices and learning that form part ! Professor of Law & Director, Institute of Technology Law, National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan. -

Secret in the Stone

Also by Kamilla Benko The Unicorn Quest WPS: Prepress/Printer’s Proof 9781408898512_txt_print.pdf November 15, 2018 13:06:25 WPS: Prepress/Printer’s Proof 9781408898512_txt_print.pdf November 15, 2018 13:06:25 “WAR CHANT” Axes chop And hammers swing, Soldiers stomp, But diamonds gleam. Mothers weep And fathers worry, But only war Can bring me glory. Emeralds shine And rubies mourn, But there’s no mine For unicorn’s horn. Axes chop And hammers swing, My heart stops, But war cries ring. Gemmer Army Marching Chant Lyrics circa 990 Craft Era Composer unknown CHAPTER 1 Graveyard. That was the first word that came to Claire Martinson’s mind as she took in the ruined city ahead of her. The second and third words were: Absolutely not. There was no way this could be the city they’d been seeking—the Gem- mer school where Claire would learn how to perfect her magic. Where she was going to figure out how to bring unicorns back to Arden. This was . “A ghost town,” Claire whispered. “Are you sure it’s Stonehaven?” Sophie asked, and Claire was glad to hear some apprehension in her older sister’s voice. If Sophie, who at the age of thirteen had already explored a magical land by herself, defeated a mysterious illness, and passed sixth grade, wasn’t feeling great about their final desti- nation, then maybe Claire wasn’t such a coward after all. “It looks so . .” “Creepy?” Claire offered. Sophie tightened the ribbon on her ponytail. “Desolate,” she finished. Desolate, indeed. Stone houses stood abandoned, their win- dows as empty as the sockets of a skull. -

Digital Technologies and Traditional Cultural Expressions: a Positive Look at a Difficult Relationship Mira Burri*

International Journal of Cultural Property (2010) 17:33–63. Printed in the USA. Copyright © 2010 International Cultural Property Society doi:10.1017/S0940739110000032 Digital Technologies and Traditional Cultural Expressions: A Positive Look at a Difficult Relationship Mira Burri* Abstract: Digital technologies have often been perceived as imperilling tradi- tional cultural expressions (TCE). This angst has interlinked technical and so- ciocultural dimensions. On the technical side, it is related to the affordances of digital media that allow instantaneous access to information without real loca- tion constraints, data transport at the speed of light and effortless reproduction of the original without any loss of quality. In a sociocultural context, digital technologies have been regarded as the epitome of globalization forces—not only driving and deepening the process of globalization itself but also spreading its effects. The present article examines the validity of these claims and sketches a number of ways in which digital technologies may act as benevolent factors. It illustrates in particular that some digital technologies can be instrumentalized to protect TCE forms, reflecting more appropriately the specificities of TCE as a complex process of creation of identity and culture. The article also seeks to reveal that digital technologies—and more specifically the Internet and the World Wide Web—have had a profound impact on the ways cultural content is created, disseminated, accessed and consumed. It is argued that this environ- ment may have generated various opportunities for better accommodating TCE, especially in their dynamic sense of human creativity. Digital technologies have often been perceived as imperiling traditional cultural expressions (TCE). -

Issues and Options for Traditional Knowledge Holders in Protecting Their Intellectual Property

CHAPTER 16.6 Issues and Options for Traditional Knowledge Holders in Protecting Their Intellectual Property stepHen A. HAnsen, American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Science and Human Rights Program, U.S.A. JUstin w. van Fleet, Principal Consultant and Director, The Advance Associates, LLC, U.S.A. ABSTRACT continued survival. Key examples of TK are these Traditional knowledge (TK) is the information that peo- uses of biological resources: ple in a given community, based on experience and adapt- • plao-noi in Thailand for the treatment of ed to local culture and environment, have developed over time and that continues to develop. This knowledge is ulcers used to sustain the community and its culture, as well • the hoodia cactus by Kung Bushmen in as the biological resources necessary for the continued Africa to stave off hunger survival of the community. Since 1948, international hu- • turmeric in India for wound-healing man-rights standards have recognized the importance of protecting intellectual property. Yet, to date, intellectual • ayahuasca in the Amazon basin for sacred property (IP) rights are not adequately extended to the religious and healing purposes holders of TK. The requirements for IP rights protections • j’oublie in Cameroon and Gabon as a under current IP regimes remain largely inconsistent with sweetener the nature of TK. As a result, it is neglected and consid- ered part of the public domain with no protections or benefits for the knowledge holders, or expropriated for TK includes mental inventories of local bio- the financial gains of others, often referred to as biopiracy. logical resources, animal breeds, and local plant, This chapter presents basic IP concepts in the context of crop, and tree species. -

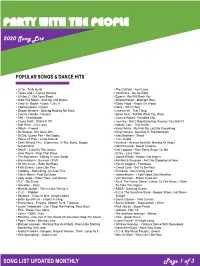

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

Traditional Knowledge

Traditional Knowledge FACT WHAT IS TRADITIONAL SHEET KNOWLEDGE? Presented by the Traditional Knowledge, often abbreviated Intellectual as TK, refers to the holistic total of an Property Issues in indigenous people’s understanding of Cultural Heritage the world. While the term is often used Project. in relation to oral history, its bounds are much broader. Traditional Knowledge can refer to knowledge of past events, but also encompasses peoples’ embodied practices, spirituality, morality, ideologies, modes of artistic (or abstract) expression, and the ways in which knowledge is acquired and passed on through WHY IS TK IMPORTANT generations. Traditional Knowledge TO COMMUNITIES? systems extend into the present, and are alive and constantly adapted in • Connecting to the past: TK represents a order to remain relevant to contemporary powerful link to a community’s past. It offers indigenous life. The term is predominantly information about a people’s history, the used to designate those knowledge land they have lived on, how they procured systems that are markedly different from the and processed resources, and their dominant Western systems of knowledge. relationships to other communities, other species, and the cosmos. • Expressing the present: TK informs a community’s self-identity—how they understand themselves, each other, and WHO “OWNS” TK? (TK AS how they fit in the wider world. To know how one’s ancestors lived, what they valued, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY): and what they knew is vitally important to understanding who one is in the present. In • Researchers in fields as such diverse as many cases, practices based on TK—from archaeology, biotechnology, and natural harvesting plants to telling stories—connect resource management are increasingly generations, both living and long gone. -

Traditional Knowledge, Innovation and Practices

Living in harmony with nature Traditional Knowledge, Innovation and Practices Traditional knowledge is the knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities around the world. Developed from experience gained over centuries and adapted to the local culture and environment, it is transmitted orally from generation to generation. It tends to be collectively owned and takes the form of stories, songs, folklore, proverbs, cultural values, beliefs, rituals, community laws, local language, and agricultural practices, including the development of plant species and animal breeds. Sometimes it is referred to as an oral tradition for it is practiced, sung, danced, painted, carved, chanted and performed down through millennia. Traditional knowledge is mainly of a practical nature, particularly in such fields as agriculture, fisheries, health, horticulture, forestry and environmental management in general. Appreciation of the value of traditional knowledge is growing. This knowledge is valuable not only to those who depend on it in their daily lives, but to modern industry and agriculture as well. Many widely used products, such as plant-based medicines, health products and cosmetics, are derived from traditional knowledge. Other such valuable products include agricultural and non-wood forest products as well as handicraft. Traditional knowledge can make a significant contribution to sustainable development. Most indigenous and local communities are situated in areas where the vast majority of the world’s genetic resources are found. Many of them have cultivated and used biodiversity in a sustainable way for thousands of years. Some of their practices have been proven to enhance and promote biodiversity at the local level and aid in maintaining healthy ecosystems. -

4.7 the Sword in the Stone

4.7 The Sword in the Stone (King Arthur, famous in legends and history as one of the bravest and noblest Kings of Britain, grew up as an orphaned youth, before Destiny intervened, in the form of his protector and guardian, Merlin the Magician, to reveal his true identity to the people of Britain.) In ancient Britain, at a time when the land was invaded by wild barbarians, the good and noble Lord Uther fought them bravely and drove them away from his land. The people made him king of Britain and gave him the title, Pendragon, meaning Dragon’s head. King Uther Pendragon ruled Britain wisely and well; the people were content. But very soon, the king died; it was thought that he had been poisoned by some traitors. There was no heir to the throne of British. The powerful Lords and Knights who had been kept under control by King Uther, now began to demand that one of them should be crowned King of Britain. Rivalry grew amongst the Lords, and the country as a whole began to suffer. Armed robbers roamed the countryside, pillaging farms and fields. People felt unsafe and insecure in their own homes. Fear gripped the country and lawlessness prevailed over the divided kingdom. Nearly sixteen years had passed since the death of Lord Uther. All the Lords and Knights of Britain had assembled at the Great Church of London for Christmas. On Christmas morning, just as they were leaving the Church, a strange sight drew their attention. In the churchyard was a large stone, and on it an anvil of steel, and in the steel a naked sword was held, and about it was written in letters of gold, ‘Whoso pulleth out this sword is by right of birth King of England.’ Many of the knights could not hold themselves back.