The Dynamics of Conflict in the Multiethnic Union of Myanmar PCIA - Country Conflict-Analysis Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Outline of the History of the Communist Party of Burma

A SHORT OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF .· THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF BURMA I Burma was an independent kingdom before annexation by the British imperialist in 1824. In 1885 British imperialist annexed whole of Burma. Since that time, Burmese people have never given up their fight for regaining their independence. Various armed uprisings and other legal forms of strug gle were used by the Burmese people in their fight to regain indep~ndence. In 19~8 the biggest and the broadest anti-British general _strike over-ran the whole country. The workers were on strike, the peasants marched up to Rangoon and all the students deserted their class-room to join the workers and peasants. It was an unprecendented anti-British movement in Burma popularly called in Burmese as "1300th movement". Out of this national and class struggle of the Burmese people and working class emerges the Communist Party of Burma. II The Communist Party of Burma was of!i~ially founded on 15th ~_!l_g~s_b 1939 by _!!nitil)K all MarxisLgr.9J!l!§ in Burma, III From the day of inception, CPB launched an active anti-British struggles up till 1941. It was the core of CPB leadership that led ahti British struggles up till the second world war. IV In 1941, after the Hitlerites treacherously attacked the Soviet Union, CPB changed its tactics and directed its blows against the fascists. v In 1942, Burma was invaded by the Japanese fascists. From that time onwards up till 1945, CPB worked unt~ringly to oppose the Japanese fa~ists 1 . -

Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05k6p059 Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 10(2) Author Guyon, Rudy Publication Date 1992 DOI 10.5070/P8102021999 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California COMMENTS VIOLENT REPRESSION IN BURMA: HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE GLOBAL RESPONSE Rudy Guyont TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................ 410 I. SLORC AND THE REPRESSION OF THE DEMOCRACY MOVEMENT ....................... 412 A. Burma: A Troubled History ..................... 412 B. The Pro-Democracy Rebellion and the Coup to Restore Military Control ......................... 414 C. Post Coup Elections and Political Repression ..... 417 D. Legalizing Repression ........................... 419 E. A Country Rife with Poverty, Drugs, and War ... 421 II. HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN BURMA ........... 424 A. Murder and Summary Execution ................ 424 B. Systematic Racial Discrimination ................ 425 C. Forced Dislocations ............................. 426 D. Prolonged Arbitrary Detention .................. 426 E. Torture of Prisoners ............................. 427 F . R ape ............................................ 427 G . Portering ....................................... 428 H. Environmental Devastation ...................... 428 III. VIOLATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW ....... 428 A. International Agreements of Burma .............. 429 1. The U.N. -

DASHED HOPES the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS DASHED HOPES The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Background ..................................................................................................................... 6 II. Section 66(d) -

Art of Not Being Governed

they lack the substance: a taxpaying subject population or di- rect control over their constituent units, let alone a standing army. Hill polities are, almost invariably, redistributive, com- petitive feasting systems held together by the benefits they are able to disburse. When they occasionally appear to be rela- The Art of Not Being tively centralized, they resemble what Barfield has called the Governed “shadow-empires” of nomadic pastoralists, a predatory periph- ery designed to monopolize trading and raiding advantages at An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia the edge of an empire. They are also typically parasitic inthe sense that when their host-empires collapse, so do they.45 James C. Scott Zones of Refuge There is strong evidence that Zomia is not simply a region of resistance to valley states, but a region of refuge as well.46 By “refuge,” I mean to imply that much of the population in the hills has, for more than a millennium and a half, come there to evade the manifold afflictions of state-making projects in the valleys. Far from being “left behind” by the progress of civiliza- 45 Thomas Barfield, “The Shadow Empires: Imperial State Formation along the Chinese-Nomad Frontier,” in Empires: Perspectives from Archaeol- ogy and History, ed. Susan E. Alcock, Terrance N. D’Altroy, et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 11–41. Karl Marx identified such para- sitic, militarized peripheries engaged in slave-raiding and plunder on the fringe of the Roman Empire as “the Germanic mode of production.” For the best account of such secondary state formation by the Wa people, see Mag- nus Fiskesjö, “The Fate of Sacrifice and the Making of Wa History,” Ph.D. -

Who They Are

Zomi: Who They Are Zomi[1] is the name of a major tribe found in various parts of South and South East Asia. The term Zomi meaning, Zo People[2] is derived from the generic name ‘Zo’, the progenitor of the Zomi. They are found in northwestern Myanmar, northeastern India and Bangladesh. Anthropologists classify them as Tibeto-Burman speaking member of the Mongoloid race. In the past they were little known by this racial nomenclature. They were known by the non-tribal plain peoples of Myanmar, Bangladesh and India as Chin, Kuki, or Lushai. Subsequently the British employed these terms to christen those ‘wild hill tribes’ living in the “un-admiral. They are Zomi not because they live in the highlands or hills, but are Zomi and call themselves Zomi because they are the descendants of their great great ancestor, ‘Zo'”.[3] ZomiRadio.Org Zomi: Who They Are This map is pointing out Zomi Inhabited Areas from the immemorial they occupied. Table of Contents Geographical Locaton History Who are the Zomi The Generic Name The Origin Of The Name Meaning Of The Name Generic Name / Imposed Names Chin Kuki Lushai Mizo and Zomi Adoption of Zomi Nomenclature Zomi Nationalism Common Race Common Religion Common Language Common History Common Political Aspiration Geographical Contiguity Common Culture Clan Songs ZomiRadio.Org Zomi: Who They Are Agamous Marriage Common Folktales Hair Dress / Styles Belief in Common Origin Common System of Naming a Child Early History and Migration Archaeological Remains Entry Into Zogam History of Zomi Struggle Colonial Rule -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

A History of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964)

University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Year A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964) Kyaw Zaw Win University of Wollongong Win, Kyaw Zaw, A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964), PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2008. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/106 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/106 A HISTORY OF THE BURMA SOCIALIST PARTY (1930-1964) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong By Kyaw Zaw Win (BA (Q), BA (Hons), MA) School of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts July 2008 Certification I, Kyaw Zaw Win, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Kyaw Zaw Win______________________ Kyaw Zaw Win 1 July 2008 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Glossary of Key Burmese Terms i-iii Acknowledgements iv-ix Abstract x Introduction xi-xxxiii Literature on the Subject Methodology Summary of Chapters Chapter One: The Emergence of the Burmese Nationalist Struggle (1900-1939) 01-35 1. Burmese Society under the Colonial System (1870-1939) 2. Patriotism, Nationalism and Socialism 3. Thakin Mya as National Leader 4. The Class Background of Burma’s Socialist Leadership 5. -

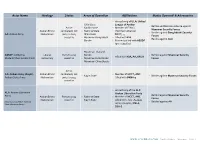

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

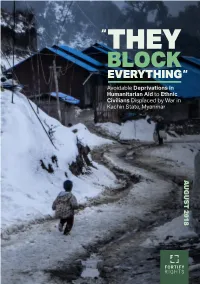

They Block Everything

Cover: Border Post 6 camp for displaced “ civilians near the China border in Myanmar’s Kachin State. Myanmar government restrictions on humanitarian aid have resulted in shortages of blankets, clothing, THEY bedding, and other essential items, making harsh winters unnecessarily difficult for displaced civilians. ©James Higgins / Partners Relief and BLOCK Development, February 2016 EVERYTHING“ Avoidable Deprivations in Humanitarian Aid to Ethnic Civilians Displaced by War in Kachin State, Myanmar Fortify Rights works to ensure human rights for all. We investigate human rights violations, engage people with power on solutions, and strengthen the work of human rights defenders, affected communities, and civil society. We believe in the influence of evidence-based research, the power of strategic truth- telling, and the importance of working closely with individuals, communities, and movements pushing for change. We are an independent, nonprofit organization based in Southeast Asia and registered in the United States and Switzerland. TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 8 METHODOLOGY � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 17 BACKGROUND �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 19 I. RESTRICTIONS ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 25 II� IMPACTS OF AID RESTRICTIONS ON DISPLACED POPULATIONS IN KACHIN STATE� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Political Monitor No.7

Euro-Burma Office 20 March – 1 April 2016 Political Monitor 2016 POLITICAL MONITOR NO. 7 OFFICIAL MEDIA MYANMAR ENTERS NEW ERA President Htin Kyaw took his oath of office at the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw on 30 March. In his inaugural speech, he said his government will strive to amend the current constitution. “I am responsible for the emergence of a constitution that will be in accord with the democratic norms suited to our country. I am also aware that I need to be patient in realising this political objective, for which the people have long aspired,” said the president. He said his government will seek to implement four policies: national reconciliation; internal peace; the emergence of a constitution that will produce a democratic, federal union; and the improvement of the quality of life of the majority of the people. Following the swearing-in ceremony at the parliament, a ceremony marking the handover of presidential duties from out-going President Thein Sein to incoming President Htin Kyaw was held at the Credentials Hall of the Presidential Palace in Nay Pyi Taw. The two vice presidents, Myint Swe and Henry Van Thio as well as the new government ministers were also sworn in on 30 March in Nay Pyi Taw. (Please see Appendix A for full text of the President Htin Kyaw’s inaugural speech).1 NLD CREATES TO “STATE COUNCILLOR” ROLE FOR AUNG SAN SUU KYI The Amyotha Hluttaw (Upper House) agreed on 31 March to discuss a special bill that would create the post of the State Counsellor for NLD Chair Aung San Suu Kyi in the new cabinet. -

CHAPTER 3 Myanmar Security Trend and Outlook:Tatmadaw in a New

CHAPTER 3 Myanmar Security Trend and Outlook: Tatmadaw in a New Political Environment Tin Maung Maung Than Introduction In March 2016, the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF), or Myanmar Defence Services (MDS) which goes by the name “Tatmadaw (Royal Force),” supported the smooth transfer of power from President Thein Sein (whose Union Solidarity and Development Party lost the election) to President Htin Kyaw (nominated by the National League for Democracy that won the election).1 Despite speculations that the winning party and the Tatmadaw would lock horns as the former challenges the constitutionally-guaranteed political role of the military, the two protagonists seemed to have arrived at a modus vivendi that allowed for peaceful coexistence throughout the year. On the other hand, the last quarter of 2016 saw two seriously difficult security challenges that took the MDS by surprise both in terms of ferocity and suddenness. The consequences of the two violent attacks initiated by Muslim insurgents in the western Rakhine State, and an alliance of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the northern Shan State, have gone beyond purely military challenges in view of their sheer complexity involving complicated issues of identity, ethnicity, and historical baggage as well as socio-economic and political grievances. Occurring at the border fo Bangladesh, the Rakhine conflagration, with religious and racial undertones, invited unwanted attention from Muslim countries while the fighting in the north bordering China raised concerns over potential Chinese reaction to serve its national interest. As such, Tatmadaw’s massive response to these challenges came under great scrutiny from the international community in general and human rights advocacy groups in particular. -

Youths in Non-Military Roles in an Armed Opposition Group on the Burmese-Thai Border

Brown, Sylvia (2012) Youths in non-military roles in an armed opposition group on the Burmese-Thai border. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/15634 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Youths in non-military roles in an armed opposition group on the Burmese-Thai border Sylvia Brown 2012 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Development Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London Statement of Original Work I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination.