Theories of Personality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Descriptive Study of Erikson's Psychosocial

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 5-2021 THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES Anastasiya Samsanovich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Samsanovich, Anastasiya, "THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES" (2021). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 1230. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1230 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Social Work by Anastasiya Samsanovich May 2021 THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Anastasiya Samsanovich May 2021 Approved by: Joseph Rigaud, Faculty Supervisor, Social Work Armando Barragán, M.S.W. Research Coordinator © 2021 Anastasiya Samsanovich ABSTRACT Theories shape society and become a powerful influence on major social decisions. While society has changed over time, some theories—developed decades ago—have remained the same. Among them is the Psychosocial Development Theory developed in the early 1960s by German-American developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst Erik Erikson. -

![Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6594/play-and-the-young-child-musical-implications-pub-date-88-note-23p-346594.webp)

Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 934 PS 021 454 AUTHOR Brophy, Tim TITLE Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Development; Developmental Psychology; Early Childhood Education; *Learning Theories; Literature Reviews; *Music Education; *Orff Method; *Piagetian Theory; *Play; *Theory Practice Relationship ABSTRACT After noting the near-universal presence of rhythmic response in play in all cultures, this paper looks first at the historical development of theories of play, and then examines current theories of play and their implications in the teaching of music to young children. The first section reviews 19th and early 20th century theories of play, including Schiller's surplus energy theory, Hall's recapitulation theory. Groos's instinct-practice theory, Patrick's relaxation theory, and Froebel's insights into children's play and its importance in psychological and educational development. The next section provides an overview of more recent theories of play, including Parten's model of levels of social play and Freud's and Erikson's psychoanalytic theory of play. The paper pays particular attention to the role of play in Piaget's cognitive-development theory and Piaget's stages of play development from practice play to symbolic play to games with rules. The final theorist discussed is Sutton-Smith, who proposed the existence of rational and irrational play. The next section discusses the difficulty in integrating the many differing views of play and reviews Frost's efforts in this area. The final section focuses on early childhood music education, particularly Orff Schulwerk, in which play is used as a primary tool for learning. -

Finding Meaning in Later Life Janet Anderson Yang, Ph.D

Finding Meaning in Later Life Janet Anderson Yang, Ph.D. Krista McGlynn, Breanna Wilhelmi, Heritage Clinic, a division of the Center for Aging Resources [email protected] 1 Helping Clients develop Meaning • Meaningful roles in family & the community • Meaningful activities in the community and/or individually at home • Meaning as an attitude • Meaning & Hope intertwined 2 Later life’s losses can make it harder to find meaning: • Can make it harder (physically & mentally) to follow past meaningful pursuits • Can make it harder to develop new meaningful activities/roles • Can make it harder to find hope 3 Existential Meaning in the face of loss How can we help older clients build meaning and hope when faced with loss or decline? 4 Existential Meaning in the face of loss How can we help clients improve their mental health and quality of life through development of altered perspectives, existential meaning, wisdom, integrity, spirituality? 5 Viktor Frankl (1980) stated that there are 3 avenues to meaning 6 Existential Meaning • Victor Frankl (1980) stated that there are 3 avenues to meaning: – Creating a work or doing a deed; – Experiencing something or encountering someone; – Attitudes: “Even if we are helpless victims of a hopeless situation, facing a fate that cannot be changed, we may rise above ourselves, grow beyond ourselves and by so doing change ourselves.” 7 Existential Meaning in the face of loss Developing meaning is one approach which may help. 8 Meaning • Robert Neimeyer counsels helping bereaved clients develop and internalize sense of attachment security with newly constructed meaning. • Martin Horrowitz recommends following trauma, helping clients create new meaning in a world which allows/permits such trauma to occur. -

Person-Centred Therapy Vs. Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy

PERSON-CENTRED THERAPY VS. RATIONAL EMOTIVE BEHAVIOUR THERAPY The purpose of this paper is to present a brief comparison of the approach to psychotherapy of Carl Rogers and Albert Ellis. I have selected Albert Ellis for comparative purposes since he was one of the other therapists participating with Rogers in the film “Three Approaches to Psycotherapy” , made in 1964, centering on interviews with the client “Gloria”. Person-Centered Therapy Rogers first formulated the essentials of Person-Centered Therapy (PCT), an approach to helping individuals and groups in conflict, in 1940. At the time it was a revolutionary hypothesis that a self-directed growth process would follow the provision and reception of a particular kind of relationship characterized by genuineness, non-judgmental caring, and empathy. Its most fundamental and pervasive concept is trust. The foundation of Rogers’ approach is a human being’s actualizing tendency towards the realization of his or her full potential; which he described as a formative tendency observable in the movement toward 134greater order, complexity and interrelatedness. The person-centered approach is built on trust that individuals and groups can set their own goals and monitor their own progress towards them. It assumes that the clients can be trusted to select their own therapist, choose the frequency and length of their therapy, talk or be silent, decide what needs to be explored, achieve their own insights, and be the architects of own lives. Moreover, groups can be trusted to develop processes right for them and to resolve conflicts in the group. In Person-Centered Therapy, the therapist provides continuous and constant empathy for the client's perceptions, meanings and feelings. -

Nondirective Counseling

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Social Sciences 140 Nondirective Counseling Effects of Short Training and Individual Characteristics of Clients BY ERIK RAUTALINKO ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2004 ! "#$ % & % % ' ( ) * *( + , -( !( . &( -%% % ) & / . % . ( 0 ( ! ( 12 ( ( /3 45$$!51 "15! & * & 6 % ( / % % . + & 7 & % % & & ( ) * %* * % & & ( ) % %% % & & 8 * %% % ( ) 7 5 9' /5///: ( / ' / * +% & 9+;< , % &: , % % & & ( ) & +; , * % &( ) * * %% ( / ' // & * % % +; & % & ( 0 & , 7 % * & & % =& % =& * ( / ' /// * & 7 +; 5 7 * =& * %% , & ( +; & * 5 7 =&6 & * , & ( / & %% , & 8 % % , % & , & ( & % & 5 7 & , & ! " #! $% &''(! ! )*(&+' ! > -, + , ! / 25?!4 /3 45$$!51 "15! # ### 5!$$ 9 #@@ (,(@ A B # ### 5!$$: LIST OF PAPERS Paper I: Rautalinko, E., & Lisper, H.-O. (2004). Effects of training reflective listening in a corporate setting. Journal of Business and Psychology, 18, 281-299. Paper II: Rautalinko, E., Lisper, H.-O., & Ekehammar, B. (2004). Training reflective listening -

Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship

Éisteach Volume 14 l Issue 2 l Summer 2014 Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship by Ian Woods Abstract This article gives a brief biographical sketch of Carl Rogers (1902-1987) and Martin Buber (1878-1965) and summarises their respective views on relationship before outlining the public dialogue in which they engaged in 1957. The outline concentrates on the part of the dialogue dealing with the therapist-client relationship and indicates some of the essential points of the exchanges between the two men, drawing out their differing perspectives. As well as commenting also on Brian Thorne’s view of the dialogue, the author’s own views are indicated both on the content of the dialogue and its implications for practice. The two men. assumption of power in 1933. He 1937 was published in English as “I arl Rogers and Martin Buber met had by then become the leading and Thou”. Cin public dialogue on 18 April interpreter of Hasidism and Jewish Following an enforced departure 1957 in the University of Michigan, mysticism and had begun what from Germany in 1938 (the same U.S.A. There was an age difference became a lifetime’s large literary year as Freud’s move to England), of 24 years between them, Buber output including more than sixty Buber became professor at the being 79 and Rogers 55 at the volumes on religious, philosophical Hebrew University of Jerusalem until time. The difference in background and related subjects. In 1923 he his retirement in 1951. During the between the two men was even more published “Ich und Du” which in early years of the State of Israel, he considerable. -

Erikson's Theory of Psychosocial Development

Erikson 1 Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development Moin Syed University of Minnesota Kate C. McLean Western Washington University To appear in: E. Braaten & B. Willoughby (Eds.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Intellectual and Developmental Disorders Contact: [email protected] or [email protected] Erikson 2 Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development is the first, and arguably most influential, lifespan theory of development. Erikson’s writings are extensive and complicated, covering quite a bit of conceptual ground. He mixed detailed treatments with vague proclamations, and returned to the same themes repeatedly throughout his career. These qualities of his work have led some to refer to his work as having “Rorschach‐like” qualities, where different readers glean and interpret his words based on their own interests and views. Thus, it is a fool’s task to attempt to represent Erikson in full or to detail the “true” nature of Erikson’s theory. Accordingly, this article contains a description of the primary thematic elements of the theory. Erikson was highly influenced by Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of development, but extended it in two substantial ways. First, Freud’s focus was limited to childhood, arguing that the bulk of personality is formed around age five (following the phallic stage). In contrast, Erikson developed a lifespan theory; that is, he theorized about the nature of personality development as it unfolds from birth through old age. Second, Freud’s theory is considered a psychosexual theory of development, emphasizing the importance of sexual drives and genitalia in how children develop. Erikson’s theory is considered psychosocial, emphasizing the importance of social and cultural factors across the lifespan. -

1 the Eight Stages of Development, Created by Erik Erikson (1956), Is a Widely Used and Universally Accepted Model Explaining Th

THE IMPACT OF EXPOSURE TO DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ON CHILD DEVELOPMENT The Eight Stages of Development, created by Erik Erikson (1956), is a widely used and universally accepted model explaining the developmental tasks involved in the social and emotional development of children that continues into adulthood.2 Each developmental stage includes a major crisis that the individual must resolve in order to move to the next stage as a socially and emotionally healthy individual. If crises are not overcome, pathology or developmental difficulty may result. The five stages of development included below are: Infancy, Early Childhood, Play Age, School Age, and Adolescence. Erikson’s model also includes three stages (Young Adulthood, Middle Adulthood, and Later Adulthood) that are not covered in this document due to the focus on childhood exposure to domestic violence. Exposure to domestic violence at any age can create delays in the accomplishment of important developmental tasks. 7 However, there are several outside factors that mitigate the impact of childhood exposure including: • The severity and duration of trauma, 11 • Developmental maturity (how far along the child is in his or her personality development when the trauma occurs), 8, 11 • Temperament, 11 • Personality make-up • Cognitive and emotional capacity, 7, 9 • Achievement, 7 • Self-esteem • Characteristic coping style, 5, 7 • Parental interpretations or expressions of parental distress, 10 • Availability of support, 5 and • Age.8 In addition, children in shelters may have higher levels of trauma symptomology given the added stressors of moving suddenly, being separated from family, friends, school, and community, and the often chaotic experience of shelter life.6 The charts below provide bulleted lists describing the potential signs or symptoms of trauma that may result from childhood exposure to domestic violence. -

Winds of Change for Client-Centered Counseling

WINDS OF CHANGE FOR CLIENT-CENTERED COUNSELING C. H. PATTERSON Humanistic Education and Development, 1993, 31, 130-133. In Understanding Psychotherapy: Fifty Years of Client-Centered Theory and Practice. PCCS Books, 2000. The winds of change they are ablowing. Client-centered counseling should be growing. The winds of change are blowing on client-centered counseling (among others, Cain, 1986, 1989a, 1989b, 1989c, 1990; Combs, 1988; Sachse, 1989; Sebastian, 1989). In the 3 years following the death of Carl Rogers, many were expressing dissatisfaction with ''traditional'' or "pure'' client-centered counseling and were engaged in trying to supplement it, extend it, and modify it. The basic complaint seems to be that the counselor conditions specified by Rogers (1957) are not sufficient. Tausch, at the International Conference on Client-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapy in Belgium in 1988, is quoted by Cain (1989c) as stating that client-centered therapy, in its pure form, is not effective for some clients and insufficient for others. Cain (1989c) commented on Gendlin's (1988) plenary address at the Belgium conference, noting that "some consider Gendlin's work a creative extension of client-centered therapy, while others contend that experiential therapy is simply incompatible with the theory and practice of client-centered therapy" (pp. 5-6). Brodley (1988) belongs to the latter group, judging from her paper at the same conference "Client-Centered and Experiential-Two Different Therapies.'' Cain (1989c) reported that Gendlin said he -

Personal Construct Psychology

WHAT WE EXPECT WHAT WE GET WHAT WE GET How did we get to this…and how do we recover? NEW AND IMPROVED THEORY? OR….. SAME OLE’ THING…WITH A NEW LOOK. Ecclesiastes 1:9 Structure of Sanctuary “Given the evidence that treatments are about equally effective, that treatments WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT delivered in clinical settings are PSYCHOTHERAPY? AND WHAT IS THERE LEFT TO DEBATE? effective (and as effective as that BRUCE E. WAMPOLD, PH.D., provided in clinical trials), that ABPPZAC E. IMEL, PH.D. 2018 the manner in which treatments are provided are much more important than which treatment is provided, mandating particular treatments seems illogical.” “THE DEVELOPMENT OF A THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP IS THE MOST ACCURATE INDICATOR OF A POSITIVE OUTCOME.” - J. ERIC GENTRY CARL ROGERS • January 1902-February 1987 • Person Centered Therapy • Unconditional Positive Regard + Congruence = Person Centered Treatment “I am not perfect…but I am enough.” PAUL D. MACLEAN • May 1913-December 2007 • Triune Brain • Three Distinct Brain Segments: Protoreptilian Paleomammalian Neomammalian “An interest in the brain requires no justification other than a curiosity to know why we are here, what we are doing here, and where we are going.” THE TRIUNE BRAIN Reptilian Brain Limbic Brain Neocortex ERIK ERIKSON • June 1902-May 1994 • Stages of Development • Development happens in stages with spectrum type “virutes” “Hope is both the earliest and the most indispensable virtue inherent in the state of being alive.” STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT • Traumatic Reenactment regresses an -

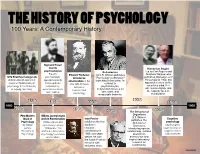

02B Psych Timeline.Pages

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY 100 Years: A Contemporary History Sigmund Freud founds Humanism Begins psychoanalysis Behaviorism Led by Carl Rogers and Freud's Edward Titchener John B. Watson publishes Abraham Maslow, who 1879 First Psychology Lab psychoanalytic introduces "Psychology as Behavior," publishes Motivation and Personality in 1954, this Wilhelm Wundt opens first approach asserts structuralism in the launching behaviorism. In experimental laboratory in that people are contrast to approach centers on the U.S. with his book conscious mind, free psychology at the University motivated by, Manual of psychoanalysis, of Leipzig, Germany. unconscious drives behaviorism focuses on will, human dignity, and Experimental the capacity for self- and conflicts. observable and Psychology measurable behavior. actualization. 1938 1890 1896 1906 1956 1860 1960 1879 1901 1913 The Behavior of 1954 Organisms First Modern William James begins B.F. Skinner Ivan Pavlov Cognitive Book of work in Functionalism publishes The Psychology William James and publishes the first Behavior of psychology By William John Dewey, whose studies in Organisms, psychologists James, 1896 article "The classical introducing operant begin to focus on Principles of Reflex Arc Concept in conditioning in conditioning. It draws cognitive states Psychology Psychology" promotes 1906; two years attention to and processes functionalism. before, he won behaviorism and the Nobel Prize for inspires laboratory his work with research on salivating dogs. conditioning. Name _________________________________Date _________________Period __________ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A Contemporary History Use the timeline from the back to answer the questions. 1. What happened earlier? A) B.F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organism B) John B. Watson publishes Psychology as Behavior 2. -

A Case Study Utilizing Music

THE EVOLVING SELF: A CASE STUDY UTILIZING MUSIC LYRICS TO STUDY EGO IDENTITY by KENT STEWART MICHAEL STEVE THOMA, COMMITTEE CHAIR DEBORAH CASPER SARA TOMEK JAMES JACKSON RICK HOUSER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Studies in Psychology, Research Methodology, and Counseling in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2019 Copyright Kent Stewart Michael 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Musicians have written about developmental transitions and the associated struggles for as long as language has been acquired and they have had the means by which to document their lyrics. Modern lyricists have ached about childhood and yearned for home as they enter young adulthood, while others have been preoccupied with romantic interests gained and lost during adolescence and beyond. Some musicians have even delved into questioning social issues, theological paradigms, decisions made by governments, and moral dilemmas in lyrics. Regardless of the developmental crisis being discussed, lyrics have been a medium in which musicians have publicly wrestled with their existential existence. Unfortunately, there is lack of representation in analyzing musical lyrics and other forms of pop culture for personality development in psychological research. This study illustrates a procedure for coding manifestations of three psychosocial stages in music lyrics from an artist’s first album to the most recent album. More specifically, identity, intimacy, and generativity themes were analyzed in John Mayer’s lyrics written during his adolescence, young adulthood, and emerging middle adulthood. Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stage theory is utilized to explain Mayer’s personality at the time each album was released and the development of personality over time.