Finding Meaning in Later Life Janet Anderson Yang, Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

EFPT Psychotherapy Guidebook • EFPT Psychotherapy Guidebook Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Olga Sidorova Published on: Jul 05, 2019 Updated on: Jul 11, 2019 EFPT Psychotherapy Guidebook • EFPT Psychotherapy Guidebook Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the most widely used evidence-based psychotherapy for improving mental health. Brief historic overview Cognitive behavioural therapy is a fusion of the behavioural and cognitive theories of human behaviour and psychopathology. Modern CBT development had three “waves”. The first, or behavioural wave was inspired and developed by notable people such as John B. Watson, Joseph Wolpe, Ivan Pavlov, Hans Eysenck, Arnold Lazarus and B. F. Skinner and comes from learning theory (Skinner et Pavlov). Learning theory is a concept describing the process of gaining, keeping and recalling knowledge. Behavioural learning theory assumes that learning is built on responses to environmental stimuli. I. Pavlov introduced a concept of classical conditioning where behaviour is a reflexive and involuntary response to stimuli. The exposure, which originated from the works of Pavlov and Watson, is a widely used instrument in CBT. It is a process of changing the unwanted, learned response or behaviour to a more desirable response. In addition to this, B. F. Skinner later shaped a concept of operant conditioning, which is based on the voluntary behaviour that is modified through the use of positive and negative reinforcements. The foundation for the second or “cognitive wave” of CBT can be tracked to numerous ancient philosophical ideas, notably in Stoicism. Stoic philosophers, particularly Epictetus, believed that logic could be used to identify and discard false beliefs that lead to destructive emotions and that individuals are responsible for their own actions, which they can examine and control through rigorous self-discipline. -

A Descriptive Study of Erikson's Psychosocial

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 5-2021 THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES Anastasiya Samsanovich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Samsanovich, Anastasiya, "THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES" (2021). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 1230. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1230 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Social Work by Anastasiya Samsanovich May 2021 THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Anastasiya Samsanovich May 2021 Approved by: Joseph Rigaud, Faculty Supervisor, Social Work Armando Barragán, M.S.W. Research Coordinator © 2021 Anastasiya Samsanovich ABSTRACT Theories shape society and become a powerful influence on major social decisions. While society has changed over time, some theories—developed decades ago—have remained the same. Among them is the Psychosocial Development Theory developed in the early 1960s by German-American developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst Erik Erikson. -

![Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6594/play-and-the-young-child-musical-implications-pub-date-88-note-23p-346594.webp)

Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 934 PS 021 454 AUTHOR Brophy, Tim TITLE Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Development; Developmental Psychology; Early Childhood Education; *Learning Theories; Literature Reviews; *Music Education; *Orff Method; *Piagetian Theory; *Play; *Theory Practice Relationship ABSTRACT After noting the near-universal presence of rhythmic response in play in all cultures, this paper looks first at the historical development of theories of play, and then examines current theories of play and their implications in the teaching of music to young children. The first section reviews 19th and early 20th century theories of play, including Schiller's surplus energy theory, Hall's recapitulation theory. Groos's instinct-practice theory, Patrick's relaxation theory, and Froebel's insights into children's play and its importance in psychological and educational development. The next section provides an overview of more recent theories of play, including Parten's model of levels of social play and Freud's and Erikson's psychoanalytic theory of play. The paper pays particular attention to the role of play in Piaget's cognitive-development theory and Piaget's stages of play development from practice play to symbolic play to games with rules. The final theorist discussed is Sutton-Smith, who proposed the existence of rational and irrational play. The next section discusses the difficulty in integrating the many differing views of play and reviews Frost's efforts in this area. The final section focuses on early childhood music education, particularly Orff Schulwerk, in which play is used as a primary tool for learning. -

Alfred Adler and Viktor Frankl's Contribution To

ALFRED ADLER AND VIKTOR FRANKL’S CONTRIBUTION TO HYPNOTHERAPY by Chaplain Paul G. Durbin Introduction: In 1972 and 1973, I went through four quarters of Clinical Pastoral Education (C.P.E.) at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington D.C. When I went there, I was a very outgoing person but inside, l felt inferior. When someone gave me a compliment, I would smile and say "Thank you," but inside I would discount the compliment. During the second quarter of C.P.E., our supervisor Chaplain Ray Stephens assigned each student, two pioneer psychologist to present a class on each. I was assigned to report on Alfred Adler and Viktor Frankl. As I prepared those two classes, I began to notice a change in how I felt about myself. I recognized that I could overcome my inferiority feelings (Adler) and that I could have meaning and purpose in my life (Frankl). As a result of those two classes, I went from low man on the totem pole to a class leader. The transformation I experienced (physically, emotionally and spiritually) could be compared to a conversion experience. Adler and Frankl have contributed to my understanding of human personality and how I relate to an individual in the therapeutic situation. Though neither were hypnotherapist, they have contributed greatly to my counseling skills, techniques and therapy. Alfred Adler: What is the difference between "Inferiority Feeling" and "Inferiority Complex" and "Superiority Complex"? What is meant by "Organ Inferiority"? "Birth Order"? "Fictional Fatalism"? "Mirror Technique?" These are concepts developed by Alfred Adler. In his youth, Adler was a sickly child which caused him embarrassment and pain. -

EXISTENTIAL PSYCHOTHERAPY Irvin D Yalom

EXISTENTIAL PSYCHOTHERAPY Irvin D Yalom ..• BasicBooks A Division ofHarperCollinsPublishers Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Yalom, Irvin D 1931- Existential psychotherapy. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Existential psychotherapy. I. Title. RC489.E93Y34 616.89 80-50553 ISBN: Q-465-Q2147-6 Copyright @ 1980 by Yalom Family Trust Printed in the United States of America Designed by Vincent Torre 25 24 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi CHAPTER 1 I Introduction 3 Existential Therapy: A Dynamic Psychotherapy 6 The Existential Orientation: Strange But Oddly Familiar 11 The Field of Existential Psychotherapy 14 Existential Therapy and the Academic Community 21 PART I I Death CHAPTER 2 I Life, Death, and Anxiety 29 Life-Death Interdependence 30 Death and Anxiety 41 The Inattention to Death in Psychotherapy Theory and Practice 54 Freud: Anxiety without Death 59 CHAPTER 3 I The Concept of Death in Children 75 Pervasiveness of Death Concern in Children 76 Concept of Death: Developmental Stages 78 Death Anxiety and the Development of Psychopathology 103 The Death Education of Children 107 CHAPTER 4 I Death and Psychopathology 110 Death Anxiety: A Paradigm of Psychopathology 112 Specialness 117 The Ultimate Rescuer 129 Toward an Integrated View of Psychopathology 141 Schizophrenia and the Fear of Death 147 An Existential Paradigm of Psychopathology: Research Evidence 152 vii Contents CHAPTER 5 I Death and Psychotherapy 159 Death as a Boundary Situation 159 Death as a Primary Source of Anxiety 187 Problems of Psychotherapy -

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) and Analytical Psychology (Søren Kierkegaard 1813-1855; Viktor Frankl 1905-1997)

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) and Analytical Psychology (Søren Kierkegaard 1813-1855; Viktor Frankl 1905-1997) Reading: Robert Aziz, C. G. Jung’s Psychology of Religion and Synchronicity (Course Reader 8). Psychological Culture: Examples of ideas that have entered into our everyday vocabulary 1. Ego 2. Complex 3. Psychological Types: Introvert and Extrovert 4. Unconscious Influences on the Psychological Theories of C. G. Jung 1. Philosophical: Existentialism and Asian Philosophy (Buddhism, Hinduism, Daoism) 2. Religious: Christianity, but Jung rejects much of institutionalized religion 3. Scientific: Description of the inner life of human beings expressed scientifically Jung's Definition of the Dark Side: The Shadow 1. Jung's view of the mind or psyche: ego consciousness, personal unconscious, and collective unconcious 2. The "Shadow" overlaps the personal unconscious and collective unconscious 3. Personal unconscious: Contents of the mind/psyche that have been Repressed from Consciousness 4. Collective unconscious: Collective or universal contents that are always there, inherent to the psyche 5. The Dark Shadow side can well up from what is inherent to the psyche as well as from what is repressed. Jung's Theory of the Mind/Psyche 1. Depth psychology: Three layer view of mind: ego consciousness, personal unconscious, and collective unconscious 2. Themes, motifs, or ARCHETYPES that exist in the inherent, collective, or universal unconscious 1. Shadow, 2. Male (Animus), Female (Anima), 3. Self (comprehensive motif or archetype, representing the whole psyche/mind) 3. For Jung, the ego is the center of waking consciousness, and the Self, the center and circumference of the Unconscious 4. Process: Goal is to achieve wholeness through individuation: Become a true individual, a whole person who is indivisible 5. -

1 from Viktor Frankl's Logotherapy to the Four Defining Characteristics of Self-Transcendence (ST) Paul T. P. Wong Introductio

1 From Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy to the Four Defining Characteristics of Self-Transcendence (ST) Paul T. P. Wong Introduction The present paper continues my earlier presentation on self-transcendence (ST) as a pathway to meaning, virtue, and happiness (Wong, 2016), in which I introduced Viktor Frankl’s (1985) two-factor theory of ST. Here, the same topic of ST is expanded by first providing the basic assumptions of logotherapy, then arguing the need for objective standards for meaning, and finally elaborating the defining characteristics of ST. To begin, here is a common-sense observation—no one can remain at the same spot for life for a variety of reasons, such as developmental and environmental changes, but most importantly because people dream of a better life and want to move to a preferred destination where they can find happiness and fulfillment. As a psychologist, I am interested in finding out (a) which destination people choose and (b) how they plan to get there successfully. In a free society that offers many opportunities for individuals, there are almost endless options regarding both (a) and (b). The reality is that not all purposes in life are equal. Some life goals are misguided, such as wanting to get rich by any means, including unethical and illegal ones, because ultimately, such choices could be self-defeating—these end values might not only fail to fill their hearts with happiness, but might also ruin their relationships and careers. The question, then, is: What kind of choices will have the greatest likelihood of resulting in a good life that not only benefits the individual but also society? My research has led me to hypothesize that the path of ST is most likely to result in such a good life. -

Erikson's Theory of Psychosocial Development

Erikson 1 Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development Moin Syed University of Minnesota Kate C. McLean Western Washington University To appear in: E. Braaten & B. Willoughby (Eds.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Intellectual and Developmental Disorders Contact: [email protected] or [email protected] Erikson 2 Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development is the first, and arguably most influential, lifespan theory of development. Erikson’s writings are extensive and complicated, covering quite a bit of conceptual ground. He mixed detailed treatments with vague proclamations, and returned to the same themes repeatedly throughout his career. These qualities of his work have led some to refer to his work as having “Rorschach‐like” qualities, where different readers glean and interpret his words based on their own interests and views. Thus, it is a fool’s task to attempt to represent Erikson in full or to detail the “true” nature of Erikson’s theory. Accordingly, this article contains a description of the primary thematic elements of the theory. Erikson was highly influenced by Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of development, but extended it in two substantial ways. First, Freud’s focus was limited to childhood, arguing that the bulk of personality is formed around age five (following the phallic stage). In contrast, Erikson developed a lifespan theory; that is, he theorized about the nature of personality development as it unfolds from birth through old age. Second, Freud’s theory is considered a psychosexual theory of development, emphasizing the importance of sexual drives and genitalia in how children develop. Erikson’s theory is considered psychosocial, emphasizing the importance of social and cultural factors across the lifespan. -

1 the Eight Stages of Development, Created by Erik Erikson (1956), Is a Widely Used and Universally Accepted Model Explaining Th

THE IMPACT OF EXPOSURE TO DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ON CHILD DEVELOPMENT The Eight Stages of Development, created by Erik Erikson (1956), is a widely used and universally accepted model explaining the developmental tasks involved in the social and emotional development of children that continues into adulthood.2 Each developmental stage includes a major crisis that the individual must resolve in order to move to the next stage as a socially and emotionally healthy individual. If crises are not overcome, pathology or developmental difficulty may result. The five stages of development included below are: Infancy, Early Childhood, Play Age, School Age, and Adolescence. Erikson’s model also includes three stages (Young Adulthood, Middle Adulthood, and Later Adulthood) that are not covered in this document due to the focus on childhood exposure to domestic violence. Exposure to domestic violence at any age can create delays in the accomplishment of important developmental tasks. 7 However, there are several outside factors that mitigate the impact of childhood exposure including: • The severity and duration of trauma, 11 • Developmental maturity (how far along the child is in his or her personality development when the trauma occurs), 8, 11 • Temperament, 11 • Personality make-up • Cognitive and emotional capacity, 7, 9 • Achievement, 7 • Self-esteem • Characteristic coping style, 5, 7 • Parental interpretations or expressions of parental distress, 10 • Availability of support, 5 and • Age.8 In addition, children in shelters may have higher levels of trauma symptomology given the added stressors of moving suddenly, being separated from family, friends, school, and community, and the often chaotic experience of shelter life.6 The charts below provide bulleted lists describing the potential signs or symptoms of trauma that may result from childhood exposure to domestic violence. -

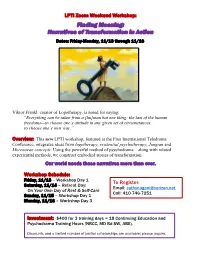

Finding Meaning: Narratives of Transformation in Action Dates: Friday-Monday, 11/13 Through 11/16

LPTI Zoom Weekend Workshop: Finding Meaning: Narratives of Transformation in Action Dates: Friday-Monday, 11/13 through 11/16 Viktor Frankl, creator of Logotherapy, is noted for saying, “Everything can be taken from a [hu]man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” Overview: This new LPTI workshop, featured at the First International Teledrama Conference, integrates ideas from logotherapy, existential psychotherapy, Jungian and Morenoean concepts. Using the powerful method of psychodrama—along with related experiential methods, we construct embodied stories of transformation. Our world needs these narratives more than ever. Workshop Schedule: Friday, 11/13 – Workshop Day 1 To Register: Saturday, 11/14 – Retreat Day: Email: [email protected] On Your Own Day of Rest & Self-Care Call: 410-746-7251 Sunday, 11/15 – Workshop Day 1 Monday, 11/16 – Workshop Day 3 Investment: $400 for 3 training days = 18 Continuing Education and Psychodrama Training Hours (NBCC, MD Bd SW, ABE). Discounts and a limited number of partial scholarships are available; please inquire. Finding Meaning: Narratives of Transformation in Action Training Objectives: At the end of this workshop, participants should be able to: ❖ Explain the significance of life narratives and narrative identity as a way of making meaning of our experience. ❖ Differentiate between a contamination/victimization narrative versus a narrative of redemption/transformation. ❖ Identify four archetypal narratives that may underlie our personal myth. ❖ Identify at least 2 holistic, integrative and experiential techniques for constructing and exploring a meaningful life narrative. Workshop Team: Catherine D. -

A Case Study Utilizing Music

THE EVOLVING SELF: A CASE STUDY UTILIZING MUSIC LYRICS TO STUDY EGO IDENTITY by KENT STEWART MICHAEL STEVE THOMA, COMMITTEE CHAIR DEBORAH CASPER SARA TOMEK JAMES JACKSON RICK HOUSER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Studies in Psychology, Research Methodology, and Counseling in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2019 Copyright Kent Stewart Michael 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Musicians have written about developmental transitions and the associated struggles for as long as language has been acquired and they have had the means by which to document their lyrics. Modern lyricists have ached about childhood and yearned for home as they enter young adulthood, while others have been preoccupied with romantic interests gained and lost during adolescence and beyond. Some musicians have even delved into questioning social issues, theological paradigms, decisions made by governments, and moral dilemmas in lyrics. Regardless of the developmental crisis being discussed, lyrics have been a medium in which musicians have publicly wrestled with their existential existence. Unfortunately, there is lack of representation in analyzing musical lyrics and other forms of pop culture for personality development in psychological research. This study illustrates a procedure for coding manifestations of three psychosocial stages in music lyrics from an artist’s first album to the most recent album. More specifically, identity, intimacy, and generativity themes were analyzed in John Mayer’s lyrics written during his adolescence, young adulthood, and emerging middle adulthood. Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stage theory is utilized to explain Mayer’s personality at the time each album was released and the development of personality over time. -

Integrating Logotherapy with Cognitive Behavior Therapy: a Worthy Challenge

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300077249 Integrating Logotherapy with Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Worthy Challenge Chapter · January 2016 DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-29424-7_18 CITATIONS READS 2 4,466 1 author: Matti Ameli 5 PUBLICATIONS 25 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Integrating Logotherapy with Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) View project Translation of a Logotherapy workbook on meaningful and purposeful goals. View project All content following this page was uploaded by Matti Ameli on 13 November 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Integrating Logotherapy with Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Worthy Challenge Matti Ameli Introduction Logotherapy, developed by Victor Frankl in the 1930s, and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) , pioneered by Aaron Beck in the 1960s, present many similarities. Ameli and Dattilio ( 2013 ) offered practical ideas of how logotherapeutic tech- niques could be integrated into Beck’s model of CBT. The goal of this article is to expand those ideas and highlight the benefi ts of a logotherapy-enhanced CBT. After a detailed overview of logotherapy and CBT, their similarities and differences are discussed, along with the benefi ts of integrating them. Overview of Logotherapy Logotherapy was pioneered by the Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl (1905–1997) during the 1930s. The Viktor-Frankl-Institute in Vienna defi nes logotherapy as: “an internationally acknowledged and empirically based meaning- centered approach to psychotherapy.” It has been called the “third Viennese School of Psychotherapy” (the fi rst one being Freud’s psychoanalysis and the second Adler’s individual psychology).