A Case Study Utilizing Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music for All Souls

GO! SINGAPORE APRIL/MAY 2019 ED SHEERAN: MUSIC FOR ALL SOULS THE PHANTOM VISITS THE SANDS THEATRE EXPLOSIVE SKECHERS FORCES SUNDOWN OF DANCE FESTIVAL – 1 – CULTURE – ENTERTAINMENT – TO-DO – RESTAURANTS – SHOPPING – EVENTS GO!singapore.pdf 1 13/7/18 4:10 PM THE WORLD’S BEST C M TEAM-BASED VIRTUAL REALITY EXPERIENCE Y CM NOW OPEN IN CHINATOWN MY CY 99% 5-star reviews since launching CMY Experience true immersion in a realistic virtual world K Travel back to ancient Egypt or even the moon Build your team now and join the adventure singapore.virtual-room.com Penthouse / 3-Bedroom Premiere Residence From 2 to 4 players per game (ages 10+) 2017 Max 22 players at once Because most of the time, you’ll be out. Which is a bit of a shame, as our serviced THE FUTURE OF THE WORLD IS IN YOUR HANDS residences are perfect for the modern living. But as we’re located at the heart of the YOU HAVE 1 HOUR TO SAVE HUMANITY! Orchard area, you’ll have Singapore’s best restaurants, shops and entertainment, right on your doorstep. And its location gives you easy access to businesses across the Come down for a FREE demo island. So when you stay at 8 on Claymore Serviced Residences, we’d love to see you, Level B3, Lucky Chinatown, 211 New Bridge Rd but we have the feeling you’ll be out. Open 10am to 10pm daily m a naged b y 8 Claymore Hill, Singapore 229572 F +65 6737 8688 E [email protected] Royal Plaza on Scotts 25 Scotts Road Singapore 228220 www.royalplazagroup.com.sg www.royalplazagroup.com.sg Fax: (65) 6737 6646 Email: [email protected] – 2 – – 3 – [email protected] +65 6966 8060 FROM THE PRESIDENT CONTENT As it happens, Singapore and I are the same And if you want to experience the “old” age. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

A Descriptive Study of Erikson's Psychosocial

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 5-2021 THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES Anastasiya Samsanovich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Samsanovich, Anastasiya, "THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES" (2021). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 1230. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1230 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Social Work by Anastasiya Samsanovich May 2021 THEORY AND DIVERSITY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF ERIKSON’S PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT STAGES A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Anastasiya Samsanovich May 2021 Approved by: Joseph Rigaud, Faculty Supervisor, Social Work Armando Barragán, M.S.W. Research Coordinator © 2021 Anastasiya Samsanovich ABSTRACT Theories shape society and become a powerful influence on major social decisions. While society has changed over time, some theories—developed decades ago—have remained the same. Among them is the Psychosocial Development Theory developed in the early 1960s by German-American developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst Erik Erikson. -

Edition 2017

YEAR-END EDITION 2017 HHHHH # OVERALL LABEL TOP 40 LABEL RHYTHM LABEL REPUBLIC RECORDS HHHHH 2017 2016 2015 2014 GLOBAL HEADQUARTERS REPUBLIC RECORDS 1755 BROADWAY, NEW YORK CITY 10019 REPUBLIC #1 FOR 4TH STRAIGHT YEAR Atlantic (#7 to #2), Interscope (#5 to #3), Capitol Doubles Share Republic continues its #1 run as the overall label leader in Mediabase chart share for a fourth consecutive year. The 2017 chart year is based on the time period from November 13, 2016 through November 11, 2017. In a very unique year, superstar artists began to collaborate with each other thus sharing chart spins and label share for individual songs. As a result, it brought some of 2017’s most notable hits including: • “Stay” by Zedd & Alessia Cara (Def Jam-Interscope) • “It Ain’t Me” by Kygo x Selena Gomez (Ultra/RCA-Interscope) • “Unforgettable” by French Montana f/Swae Lee (Eardrum/BB/Interscope-Epic) • “I Don’t Wanna Live Forever” by ZAYN & Taylor Swift (UStudios/BMR/RCA-Republic) • “Bad Things” by MGK x Camila Cabello (Bad Boy/Epic-Interscope) • “Let Me Love You” by DJ Snake f/Justin Bieber (Def Jam-Interscope) • “I’m The One” by DJ Khaled f/Justin Bieber, Quavo, Chance The Rapper & Lil Wayne (WTB/Def Jam-Epic) All of these songs were major hits and many crossed multiple formats in 2017. Of the 10 Mediabase formats that comprise overall rankings, Republic garnered the #1 spot at two formats: Top 40 and Rhythmic, was #2 at Hot AC, and #4 at AC. Republic had a total overall chart share of 15.6%, a 23.0% Top 40 chart share, and an 18.3% Rhythmic chart share. -

![Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6594/play-and-the-young-child-musical-implications-pub-date-88-note-23p-346594.webp)

Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 934 PS 021 454 AUTHOR Brophy, Tim TITLE Play and the Young Child: Musical Implications. PUB DATE [88] NOTE 23p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Development; Developmental Psychology; Early Childhood Education; *Learning Theories; Literature Reviews; *Music Education; *Orff Method; *Piagetian Theory; *Play; *Theory Practice Relationship ABSTRACT After noting the near-universal presence of rhythmic response in play in all cultures, this paper looks first at the historical development of theories of play, and then examines current theories of play and their implications in the teaching of music to young children. The first section reviews 19th and early 20th century theories of play, including Schiller's surplus energy theory, Hall's recapitulation theory. Groos's instinct-practice theory, Patrick's relaxation theory, and Froebel's insights into children's play and its importance in psychological and educational development. The next section provides an overview of more recent theories of play, including Parten's model of levels of social play and Freud's and Erikson's psychoanalytic theory of play. The paper pays particular attention to the role of play in Piaget's cognitive-development theory and Piaget's stages of play development from practice play to symbolic play to games with rules. The final theorist discussed is Sutton-Smith, who proposed the existence of rational and irrational play. The next section discusses the difficulty in integrating the many differing views of play and reviews Frost's efforts in this area. The final section focuses on early childhood music education, particularly Orff Schulwerk, in which play is used as a primary tool for learning. -

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Finding Meaning in Later Life Janet Anderson Yang, Ph.D

Finding Meaning in Later Life Janet Anderson Yang, Ph.D. Krista McGlynn, Breanna Wilhelmi, Heritage Clinic, a division of the Center for Aging Resources [email protected] 1 Helping Clients develop Meaning • Meaningful roles in family & the community • Meaningful activities in the community and/or individually at home • Meaning as an attitude • Meaning & Hope intertwined 2 Later life’s losses can make it harder to find meaning: • Can make it harder (physically & mentally) to follow past meaningful pursuits • Can make it harder to develop new meaningful activities/roles • Can make it harder to find hope 3 Existential Meaning in the face of loss How can we help older clients build meaning and hope when faced with loss or decline? 4 Existential Meaning in the face of loss How can we help clients improve their mental health and quality of life through development of altered perspectives, existential meaning, wisdom, integrity, spirituality? 5 Viktor Frankl (1980) stated that there are 3 avenues to meaning 6 Existential Meaning • Victor Frankl (1980) stated that there are 3 avenues to meaning: – Creating a work or doing a deed; – Experiencing something or encountering someone; – Attitudes: “Even if we are helpless victims of a hopeless situation, facing a fate that cannot be changed, we may rise above ourselves, grow beyond ourselves and by so doing change ourselves.” 7 Existential Meaning in the face of loss Developing meaning is one approach which may help. 8 Meaning • Robert Neimeyer counsels helping bereaved clients develop and internalize sense of attachment security with newly constructed meaning. • Martin Horrowitz recommends following trauma, helping clients create new meaning in a world which allows/permits such trauma to occur. -

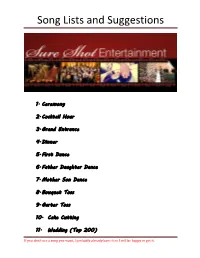

Song Lists and Suggestions

Song Lists and Suggestions 1. Ceremony 2. Cocktail Hour 3. Grand Entrance 4. Dinner 5. First Dance 6. Father Daughter Dance 7. Mother Son Dance 8. Bouquet Toss 9. Garter Toss 10. Cake Cutting 11. Wedding (Top 200) If you don’t see a song you want, I probably already have it or I will be happy to get it. Page 1 of 1 Ceremony CD 20 songs, 1.2 hours, 133.9 MB Name Time Album Artist 1 All of Me (In the Style of John Lege… 4:38 Modern Acoustic Music for Beautif… Acoustic Guitar Guy 2 At Last (String Quartet Tribute to E… 2:40 The Gay Wedding Collection Vitamin String Quartet 3 Bittersweet Symphony 3:40 Symphonic Rock Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 4 Bridal March 1:48 For a Lifetime Jonathan Cain 5 Can't Help Falling in Love 2:54 Can't Help Falling in Love - Single Haley Reinhart 6 Can't Help Falling In Love 4:32 Vitamin String Quartet Tribute to M… Vitamin String Quartet 7 Canon in D 5:24 Wedding Music: Instrumental Song… Wedding Music Experts: The O'Nei… 8 The Cello Song 3:17 The Piano Guys The Piano Guys 9 From This Moment On 4:34 Wedding Music: Instrumental Song… Wedding Music Experts: The O'Nei… 10 Here Comes the Sun 3:20 Instrumental Songs - Soft Rock Gu… Instrumental Songs Music 11 In My Life 2:27 In My Life - A Piano Tribute to the… TJR 12 Just The Way You Are 4:22 The Piano Guys 2 The Piano Guys 13 Just the Way You Are 3:14 The Modern Wedding Collection, V… Vitamin String Quartet 14 Latch (Acoustic) 3:41 Nirvana Sam Smith 15 Marry Me 3:25 Save Me, San Francisco (Bonus Tr… Train 16 Over The Rainbow, Simple Gifts 3:44 The Piano Guys The -

Erikson's Theory of Psychosocial Development

Erikson 1 Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development Moin Syed University of Minnesota Kate C. McLean Western Washington University To appear in: E. Braaten & B. Willoughby (Eds.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Intellectual and Developmental Disorders Contact: [email protected] or [email protected] Erikson 2 Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development is the first, and arguably most influential, lifespan theory of development. Erikson’s writings are extensive and complicated, covering quite a bit of conceptual ground. He mixed detailed treatments with vague proclamations, and returned to the same themes repeatedly throughout his career. These qualities of his work have led some to refer to his work as having “Rorschach‐like” qualities, where different readers glean and interpret his words based on their own interests and views. Thus, it is a fool’s task to attempt to represent Erikson in full or to detail the “true” nature of Erikson’s theory. Accordingly, this article contains a description of the primary thematic elements of the theory. Erikson was highly influenced by Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of development, but extended it in two substantial ways. First, Freud’s focus was limited to childhood, arguing that the bulk of personality is formed around age five (following the phallic stage). In contrast, Erikson developed a lifespan theory; that is, he theorized about the nature of personality development as it unfolds from birth through old age. Second, Freud’s theory is considered a psychosexual theory of development, emphasizing the importance of sexual drives and genitalia in how children develop. Erikson’s theory is considered psychosocial, emphasizing the importance of social and cultural factors across the lifespan. -

1 the Eight Stages of Development, Created by Erik Erikson (1956), Is a Widely Used and Universally Accepted Model Explaining Th

THE IMPACT OF EXPOSURE TO DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ON CHILD DEVELOPMENT The Eight Stages of Development, created by Erik Erikson (1956), is a widely used and universally accepted model explaining the developmental tasks involved in the social and emotional development of children that continues into adulthood.2 Each developmental stage includes a major crisis that the individual must resolve in order to move to the next stage as a socially and emotionally healthy individual. If crises are not overcome, pathology or developmental difficulty may result. The five stages of development included below are: Infancy, Early Childhood, Play Age, School Age, and Adolescence. Erikson’s model also includes three stages (Young Adulthood, Middle Adulthood, and Later Adulthood) that are not covered in this document due to the focus on childhood exposure to domestic violence. Exposure to domestic violence at any age can create delays in the accomplishment of important developmental tasks. 7 However, there are several outside factors that mitigate the impact of childhood exposure including: • The severity and duration of trauma, 11 • Developmental maturity (how far along the child is in his or her personality development when the trauma occurs), 8, 11 • Temperament, 11 • Personality make-up • Cognitive and emotional capacity, 7, 9 • Achievement, 7 • Self-esteem • Characteristic coping style, 5, 7 • Parental interpretations or expressions of parental distress, 10 • Availability of support, 5 and • Age.8 In addition, children in shelters may have higher levels of trauma symptomology given the added stressors of moving suddenly, being separated from family, friends, school, and community, and the often chaotic experience of shelter life.6 The charts below provide bulleted lists describing the potential signs or symptoms of trauma that may result from childhood exposure to domestic violence. -

COMPLAINT Against KTS Karaoke, Inc. and Timmy Sun Ton (Filing

Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC et al v. KTS Karaoke, Inc. et al Doc. 1 Att. 7 EXHIBIT “7” to COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTION AND DAMAGES SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHIG LLC, ET AL. V. KTS KARAOKE, INC., ET AL. (Plaintiffs’ copyrights bearing the unlicensed “Quick Hitz” brand and advertised, distributed and/or sold by the KTS Defendants) Title 1. Addicted 2. ADDICTED 3. AIRPLANES 4. AIRPLANES 5. AIRSTREAM SONG 6. ALEJANDRO 7. ALICE 8. ALL OF ME 9. ALL THE RIGHT MOVES 10. ALL TIME LOW 11. ALREADY GONE 12. ALREADY GONE 13. ANIMALS 14. ANOTHER WAY TO DIE 15. BABY 16. BABY GIRL 17. Back When 18. BAD ROMANCE 19. BATTLEFIELD 20. BATTLEFIELD 21. BE ON YOU 22. BEAUTIFUL EYES 23. BECAUSE OF YOU 24. Before He Cheats 25. BEFORE HE CHEATS 26. BEST I EVER HAD 27. BEST OF BOTH WORLDS 28. BETTER IN TIME 29. BILLIONAIRE 30. BIONIC 31. BLAME IT Dockets.Justia.com 32. BOOM BOOM POW 33. BOYS BOYS BOYS 34. BREATHE 35. BULLETPROOF 36. CHANGE 37. CHANGE 38. Cheatin' 39. Coalmine 40. Complicated 41. COUNTRY STRONG 42. CRACK A BOTTLE 43. CRACK A BOTTLE 44. CRAZIER 45. CRAZY EX GIRLFRIEND 46. CRUSH 47. CRY 48. CRY 49. CRY ME A RIVER 50. DANGEROUS 51. DEAD FLOWERS 52. DISTURBIA 53. DO YOU REMEMBER 54. Do You Want Fries With That 55. DON'T STOP THE MUSIC 56. Don't Take The Girl 57. Don't Tell Me 58. DOWN 59. DOWN 60. DOWN 61. Drugs Or Jesus 62. DYNAMITE 63. EH EH (NOTHING ELSE I CAN SAY) 64. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co.