Museological-Review-Issue-22.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining Social Media As OPR Tool

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2020-06-01 Creating a Long-Term Relationship Between a Museum and its Patrons: Examining Social Media as OPR Tool Kylie M. Brooks Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Fine Arts Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Brooks, Kylie M., "Creating a Long-Term Relationship Between a Museum and its Patrons: Examining Social Media as OPR Tool" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 8463. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8463 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Creating a Long-Term Relationship Between a Museum and Its Patrons: Examining Social Media as OPR Tool Kylie M. Brooks A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Christopher Wilson, Chair Jessica Zurcher Mark Callister School of Communications Brigham Young University Copyright © 2020 Kylie M. Brooks All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Creating a Long-Term Relationship Between a Museum and Its Patrons: Examining Social Media as OPR Tool Kylie M. Brooks School of Communications, BYU Master of Arts This qualitative research study comprised of six case studies explores museums’ practical usage of social media as an organization public relations tool. Analyzing six different museums using both surveys and interviews, this research provides a strategic, theory-based framework for any organization to utilize social media effectively by increasing public trust and engagement. -

Spanish Archaeological Museums During COVID-19 (2020): an Edu-Communicative Analysis of Their Activity on Twitter Through the Sustainable Development Goals

sustainability Article Spanish Archaeological Museums during COVID-19 (2020): An Edu-Communicative Analysis of Their Activity on Twitter through the Sustainable Development Goals Pilar Rivero, Iñaki Navarro-Neri , Silvia García-Ceballos * and Borja Aso Department of Specific Didactics, Faculty of Education, University of Zaragoza, Calle de Pedro Cerbuna, 12, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain; [email protected] (P.R.); [email protected] (I.N.-N.); [email protected] (B.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-876-554-865 Received: 22 September 2020; Accepted: 2 October 2020; Published: 6 October 2020 Abstract: On 18 March 2020, Spanish museums saw their in-person activities come to a halt. This paradigm shift has raised questions concerning how these institutions reinvented themselves and modified their edu-communicative strategies to promote heritage through active citizen participation. The present study centers on analyzing how the main Spanish archaeological museums and sites (N = 254) have used Twitter as an edu-communicative tool and analyzes the content of their hashtags through a mixed methodology. The objective is to identify the educational strategies for both transmitting information as well as interacting with users. We did it by observing and analyzing if Spanish archaeological institutions are promoting a type of quality, accessible, and egalitarian education and promoting the creation of cyber communities that ensure the sustainability of heritage through citizen participation. This paper proposes an innovative assessment of communication on Twitter based on the purpose of messages from the viewpoint of heritage education, their r-elational factor, and predominant type of learning. The main findings reveal a significant increase in Twitter activity, both in quantitative and qualitative terms: educational content is gaining primacy over the simple sharing of basic information and promotional content. -

Presentation Museumweek 2021 EN.Docx

DOCUMENT FOR CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS About the 2021 edition For seven days, cultural institutions and audiences are invited to be creative with their smartphones for this eighth edition! The health crisis caused by the coronavirus has plunged the global economy into recession. While billions of people around the world resort to culture as a source of comfort and connection, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has not spared the creative sector. In times of crisis even more, support for the creative industries is crucial, as is the spirit of creativity itself, in all its forms. It is therefore quite natural that Culture For Causes Network, a non-profit organization that supports causes of general interest on behalf of national, European or international organizations, and Art Explora, a philanthropic foundation with international, nomadic, non-collecting and digital ambitions, as well as UNESCO around the ResiliArt program, have decided to join forces for the organization of the #MuseumWeek 2021. Page 1 of 13 DOCUMENT FOR CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS The organizers of the #MuseumWeek will therefore solicit their network of more than 6,000 cultural institutions around the formula "7 days, 7 themes, 7 hashtags", with the following concrete objectives: ● To reach out to connected audiences who are not interested in Culture and Art by exposing them to original cultural content. ● To stimulate the spirit of creativity and creation in all of us and especially in young people. ● To reinforce the image of artists in society as actors who participate in the change of society Page 2 of 13 DOCUMENT FOR CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS How to participate? 1 -P repare your daily publications! Participants are invited to post cultural content and interact around these 7 hashtags, which are defined below. -

Décoloniser La Muséologie Descolonizando La Museología

Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología 2 The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen Editors Yves Bergeron, Michèle Rivet 1 Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología Series Editor / Éditeur de la série / Editor de la Serie: Bruno Brulon Soares 1. A Experiência Museal: Museus, Ação Comunitária e Descolonização La Experiencia Museística: Museos, Acción Comunitaria y Descolonización The Museum Experience: Museums, Community Action and Decolonisation 2. The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen International Committee for Museology – ICOFOM Comité International pour la Muséologie – ICOFOM Comité Internacional para la Museología – ICOFOM Editors / Éditeurs / Editores: Yves Bergeron & Michèle Rivet Editorial Committee / Comité Éditorial / Comité Editorial Marion Bertin, Luciana Menezes de Carvalho President of ICOFOM / Président d’ICOFOM /Presidente del ICOFOM Bruno Brulon Soares Academic committee / Comité scientifique / Comité científico Karen Elizabeth Brown, Bruno Brulon Soares, Anna Leshchenko, Daniel Sch- mitt, Marion Bertin, Lynn Maranda, Yves Bergeron, Yun Shun Susie Chung, Elizabeth Weiser, Supreo Chanda, Luciana -

Digital Education As a Catalyst for Museum Transformation

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CULTURAL MANAGEMENT & POLICY || Vol. 9, Issue 2, 2019 || ISSN 2663-5771 Digital education as a catalyst for museum transformation: the case of the ”Museums and New Digital Cultures” course Stefania Zardini Lacedelli University of Leicester, United Kingdom [email protected] Michele Tamma University Ca’ Foscari of Venice, Italy [email protected] Fabiana Fazzi University Ca’ Foscari of Venice, Italy [email protected] ABSTRACT To embrace digital transformation, Continuing Professional Development (CDP) has become a strategic asset. In the cultural sector, new educational needs are emerging around the concept of “digital”, but how to approach them in a way Keywords: that supports the evolution of previous roles as well as the overall organisational Museum digital change? This paper addresses the aforementioned issue through the case study of transformation a training programme, promoted by the Veneto Region and aimed at updating the digital skills of the regional cultural workforce. A qualitative study was implemented to Digital educational explore the impact of such training programme, “Museums and New Digital Cultures”, needs which involved 120 professionals from 34 cultural organisations, at both individual Continuing and organisational levels. The research outcomes show how the introduction and professional implementation of new digital practices can be a key tool in transforming the individual development evolution of different professional roles and trigger a broader organisational change. Digital practices ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Digital skills We would like to thank Giacomo Pompanin for his invaluable contribution to the Digital museum development and implementation of the CPD course. We would also like to thank the participants, without whom this research would have never been possible. -

Free Pdf to Download

The Museum Review www.themuseumreview.org Rogers Publishing Corporation NFP 2147 S. Lumber St, Suite 419, Chicago, IL 60616 www.rogerspublishing.org ©2017 The Museum Review The Museum Review is a peer reviewed Open Access Gold journal, permitting free online access to all articles, multi-media material, and scholarly research. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Putting the “social” in social media: interactive new media for museums AUNI GELLES Baltimore Museum of Industry Keywords Social media; museum marketing; new media; #musesocial; small museum; museum interaction Abstract Social media, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, is having a growing impact on museum marketing and museum audiences. Providing real examples of successful, interesting, and impactful social media campaigns, this article explores methods and helps generate ideas for museums to utilize diverse forms of social media. By participating in effective social media, museums of all types can engage in and encourage a deeper relationship individuals and other institutions. About the Author Auni Gelles is the Community Programs Manager at the Baltimore Museum of Industry. She volunteers as the speaker coordinator for the Small Museum Association conference, is a digital strategy task force member for the History Relevance Campaign, and a board member of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House. A graduate of the public history M.A. program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, she previously worked as the Assistant Director of the Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area based in Frederick, Maryland. Reach her on Twitter and Instagram @aunigelles. This article was published on November 8, 2017 at www.themuseumreview.org Reports about the impact of social media on our daily personal and professional lives are common. -

À Propos De L'édition 2021

DOCUMENT POUR LES INSTITUTIONS CULTURELLES À propos de l’édition 2021 Pendant sept jours, institutions culturelles et publics seront invités à faire preuve de créativité avec leurs smartphones à l’occasion de cette huitième édition ! La crise sanitaire provoquée par le coronavirus a plongé l'économie mondiale dans une récession. Alors que des milliards de personnes dans le monde se tournent vers la culture comme source de réconfort et de rapprochement, l'impact de la pandémie de COVID-19 n'a pas épargné le secteur créatif. En temps de crise plus encore, le soutien aux industries créatives est crucial, tout comme l’esprit de créativité en tant que tel, sous toutes ses formes. C'est donc tout naturellement que Culture For Causes Network, association à but non lucratif visant à soutenir des causes d'intérêt général pour le compte d'organisations nationales, européennes ou internationales, et Art Explora, fondation philanthropique à l’ambition internationale, nomade, sans collection et digitale, ainsi que l’UNESCO autour du programme ResiliArt, ont décidé d'unir leurs forces pour l’organisation de la #MuseumWeek 2021. Page 1 sur 13 DOCUMENT POUR LES INSTITUTIONS CULTURELLES Les organisateurs de la #MuseumWeek solliciteront donc leur réseau de plus de 6000 institutions culturelles autour de la formule « 7 jours, 7 thèmes, 7 hashtags », avec pour objectifs concrets : ● D’aller à la rencontre des publics connectés qui ne s’intéressent pas à la Culture et à l’Art en les exposant à des contenus culturels originaux ; ● De stimuler l’esprit de créativité et de création en chacun de nous et notamment celui des jeunes ; ● De renforcer l’image des artistes dans la société comme des acteurs qui participent au changement de la société Page 2 sur 13 DOCUMENT POUR LES INSTITUTIONS CULTURELLES Comment participer ? 1 – préparez des publications pour les 7 jours ! Les participants sont invités à publier des contenus et à interagir autour de ces 7 hashtags dont vous trouverez une description plus bas dans ce document. -

How Do Italian Museums Communicate Online?

[email protected] EAGLE 2014 International Conference On Information Technologies For Epigraphy And Digital Cultural Heritage In The Ancient World How do Italian Museums Communicate Online? The #svegliamuseo project and the concept of a network of digital communication professionals for the Italian cultural heritage sector. [email protected] / @thePorden testo1 [email protected] What is #svegliamuseo? #svegliamuseo is an experimental project to “wake up” Italian museums online, leveraging the power of the Web to generate network effect. 2 [email protected] What is #svegliamuseo? #svegliamuseo is an experimental project to “wake up” Italian museums online, leveraging the power of the Web to generate network effect. ! The project was founded in October 2013 with rather provocatory name and intentions (svegliamuseo means “wake up, museums”). It wanted to generate buzz around the topic of online communication in the cultural field. 3 [email protected] What is #svegliamuseo? #svegliamuseo is an experimental project to “wake up” Italian museums online, leveraging the power of the Web to generate network effect. ! The project was founded in October 2013 with rather provocatory name and intentions (svegliamuseo means “wake up, museums”). It wanted to generate buzz around the topic of online communication in the cultural field. ! Today, #svegliamuseo wants to function as a container for ideas and resources. It is a blog, a Facebook group, a Twitter account and an hashtag that are prompting communities and experts from all over the world to start a dialogue about digital media in the museum field. 4 [email protected] Why a project on museums and digital communication? Because in Italy there are 4,588 museums on an area of 301,340 km², but only a small percentage of these institutions is leveraging on the power of the web to better communicate with their audiences, real and potential. -

Décoloniser La Muséologie Descolonizando La Museología

Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología 2 The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen Editors Yves Bergeron, Michèle Rivet 1 Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología Series Editor / Éditeur de la série / Editor de la Serie: Bruno Brulon Soares 1. A Experiência Museal: Museus, Ação Comunitária e Descolonização La Experiencia Museística: Museos, Acción Comunitaria y Descolonización The Museum Experience: Museums, Community Action and Decolonisation 2. The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen International Committee for Museology – ICOFOM Comité International pour la Muséologie – ICOFOM Comité Internacional para la Museología – ICOFOM Editors / Éditeurs / Editores: Yves Bergeron & Michèle Rivet Editorial Committee / Comité Éditorial / Comité Editorial Marion Bertin, Luciana Menezes de Carvalho President of ICOFOM / Président d’ICOFOM /Presidente del ICOFOM Bruno Brulon Soares Academic committee / Comité scientifique / Comité científico Karen Elizabeth Brown, Bruno Brulon Soares, Anna Leshchenko, Daniel Sch- mitt, Marion Bertin, Lynn Maranda, Yves Bergeron, Yun Shun Susie Chung, Elizabeth Weiser, Supreo Chanda, Luciana -

The Experience Economy in Museums

The experience economy in museums MSc Business Administration – Track EMCI Supervisor: Matthijs Leendertse Isabella van Marle 10024832 Date 24-6-2016 Statement of originality This document is written by Isabella van Marle who declares to take full responsibility for the contents of this document. I declare that the text and the work presented in this document is original and that no sources other than those mentioned in the text and its references have been used in creating it. The Faculty of Economics and Business is responsible solely for the supervision of completion of the work, not for the contents. 1 Table of content 1. Introduction 5 2. Theoretical Framework 7 2.1. The Experience economy 7 2.2. Generation Y 9 2.3.1. Museum objectives 11 2.3.2. Museum challenges 12 2.4. Business model innovation 16 2.4.1. Value proposition 18 2.4.2. Customer relationship 24 2.4.3. Channel 39 3. Research methodology 33 3.1. Research design and strategy 33 3.2. Sample 34 3.3. Data collection 36 3.4. Validity and reliability 38 3.5. Data analysis 39 4. Results 40 4.1. Challenges 41 4.2. Generation Y 41 2 4.3. Value proposition 42 4.3.1. Participation and interactivity 42 4.3.2. Education vs. Entertainment 46 4.3.3. Personalization 48 4.3.4. Design 50 4.4. Customer relationship 54 4.4.1. Co-creation 57 4.4.2. Networks 58 4.5. Channel 60 4.5.1. Communication channel 60 4.5.2. Distribution channel 61 4.5.3. -

Annualreport

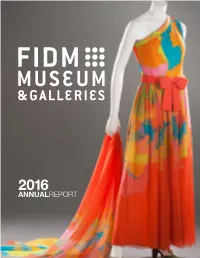

ANNUAL2016 REPORT CONTENTS 3 STRATEGIC PLAN OUTCOMES 4 ACQUISTION HIGHLIGHTS 8 EXHIBITIONS 11 CURATORIAL 15 REGISTRATION 19 COLLECTIONS MANAGEMENT 21 GALLERIES 22 PROGRAMS / EVENTS 25 SOCIAL MEDIA & BLOG 28 VOLUNTEERS & INTERNS 31 2017: THE FUTURE 34 STAFF ROSTER VISION STATEMENT To be the global resource for the study of fashion--past, present, and future. MISSION STATEMENT The FIDM Museum and Library, Inc. collects, preserves, and interprets fashion objects and support materials with outstanding design merit. It fosters student learning, public engagement, and recognition of the creative arts and entertainment industries by providing access to the collections through exhibitions, publications, and other research opportunities. 2 STRATEGIC PLAN OUTCOMES OUTCOME 1 Enhance the aesthetic and historical value of the museum’s collection through targeted acquisitions. OUTCOME 2 Improve the Museum’s stature in the museum community by implementing Best Practices as published by professional organizations; formulate a broad and systematic program of professional development that supports personal growth, accountability, and museum performance. OUTCOME 3 Achieve a high level of scholarship through exhibition texts, staff-authored publications, online publishing, collection documentation, and peer-reviewed papers; receive professional recognition for scholarly output. OUTCOME 4 Promote the Museum’s cultural presence through the use of technology and special events, such as exhibitions, lectures, and symposia. OUTCOME 5 Provide access to collections -

Strategic Plan 2020-2025

Museum & Cultural Centre Strategic Plan 2020-2025 1. Museum & Cultural Centre 2. Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................. 4 The Museum in 2025 ...................................................................... 5 History of the Museum ........................................................... 6 Profile of the Town of Lincoln .......................................................... 7 Profile of the Museum .................................................................... 8 Strategic Planning Process and Approach ........................ 13 Strategic Vision for the Museum in 2025 ........................... 24 Conclusion ............................................................................... 29 Appendix A: Compilation of funding opportunities available to Lincoln Museum and Cultural Centre: Home of the Jordan Historical Museum of the Twenty as of 2020 .................................................. 32 Appendix B: Environmental Scan and Key Issues Report prepared by TCI Management Consultant ....................................... 41 Appendix C: Community Survey Results ........................................................... 65 Appendix D: SWOT Analysis ............................................................................ 72 Appendix E: Action Timeline for Strategic Priorities .......................................... 74 oto Credit: Aerial Photography 3. Introduction Museums play an important role in making communities vibrant, welcoming, and