Before the District Hearings Panel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waikanae Park Population and Household Forecasts 2013 to 2043

Kāpiti Coast District Waikanae Park Population and household forecasts 2013 to 2043 population forecast Compiled and presented in forecast.id®. http://forecast.id.com.au/kapiti Table of contents About the forecast areas 1 Drivers of population change 6 Population summary 7 Population, households and dwellings 9 Population and age structure 12 Household types 14 Dwellings and development map 16 Population and age structure map 18 Household types map 20 Residential development 21 Net migration by age 22 Non-private dwellings 23 About the forecasts 24 Factors of population change 25 Household and suburb life cycles 27 Forecast modelling process 30 Glossary 32 copyright © 2017 .id Consulting Pty Ltd ACN 084 054 473. All rights reserved. Please read our Report Disclaimer and Copyright Notice which governs your use of this Report. Waikanae Park About the forecast areas Waikanae Park is bounded by the area above Ngarara Road and the locality of Waikanae Beach – Peka Peka to the north, the area bordering Nga Manu Nature Reserve, Waikanae Park and the locality of Waikanae-Reikorangi to the east, the Waikanae River to the south and the area close to Rutherford Drive and the locality of Waikanae Beach- Peka Peka to the west. The place name Waikanae is derived from the river of kanae (mullet) Hau saw while following Wairaka. Important Population 2017 Population 2043 Change 2017-43 Statistics 1,914 4,368 128.26% Forecast areas Waikanae Park Legend Kāpiti Coast Small areas v17.09.06-1.0.0 Source: Population and household forecasts, 2013 to 2043, prepared by .id, the population experts, February 2017. -

EPA Board of Enquiry Hon Sir John Hanley David Bunting, Environment

EPA Board of Enquiry Hon Sir John Hanley David Bunting, Environment Commissioner Glenice Paine Mark Appledoorn Intro My name is Ruben Blok and I live at 79 Belvedere Ave, Waikanae. I am a Business Intelligence consultant with a private local firm and I create analytic reporting solutions for major private and public sector organisations throughout the Australasia. I am usually not too worried about government decisions but given my field of expertise and what I have witnessed with this project something very wrong is happening here and the information does simply not add up. I oppose the NZTA Makays to Peka Peka proposal and would like to tell you my experience and explain my findings. Lead Up We moved from Auckland to Kapiti (originally to Raumati South) in 2007 to start a family and fell in love with the community and surroundings. The combination of bush, beach, and lifestyle was an easy decision. We heard about KCDCs initial proposal to create a new alternate road and bridge to Waikanae I quite liked the idea. It seems a little crazy that you can almost walk to Waikanae from Paraparaumu Beach faster than you can drive (we tested it the other day). A year or two later we received the notification from NZTA that as part of the Roads of National Significance project they were planning to upgrade the existing SH1 to future proof the national grid. We again quite optimistic when we saw the proposals (WO and EO only) and chose option EO, upgrade the existing SH1, as it had minimal impact on the existing community leaving SH1 as close to its original location as possible. -

Communitrak™ Survey

COMMUNITRAK™ SURVEY PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS OF COUNCIL SERVICES AND REPRESENTATION PREPARED AS PART OF THE PUBLIC FEEDBACK PROGRAMME FOR: WHAKATĀNE DISTRICT COUNCIL MAY / JUNE 2019 National Research Bureau Ltd PO Box 10118, Mt Eden, Auckland, New Zealand P (09) 6300 655, www.nrb.co.nz CONTENTS Page No. A. SITUATION AND OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................. 1 B. COMMUNITRAK™ SPECIFICATIONS ................................................................................. 2 C. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 6 D. MAIN FINDINGS ..................................................................................................................... 26 1. Council Services/Facilities ............................................................................................ 27 a. Satisfaction With Council Services And Facilities ........................................... 28 i. Parks And Reserves .................................................................................. 28 ii. Sportsfields ................................................................................................ 31 iii. Street Lighting ........................................................................................... 34 iv. Public Toilets ............................................................................................. 37 v. Footpaths .................................................................................................. -

Horowhenua District Council Independent Assessment Report | July 2017*

Horowhenua District Council Independent assessment report | July 2017* An independent assessment report issued by the Independent Assessment Board for the CouncilMARK™ local government excellence programme. For more information visit www.councilmark.co.nz * Period of assessment: October 2016 Horowhenua District Council assessment report 1 Assessment Summary AT A GLANCE A growing and changing district with disparity of income, young/old age profile, and increasingly diverse ethnic make-up. The current situation Horowhenua District Council is in a period of transition. Assumptions of low growth were used in the Council’s Long Term Plan for 2015-25 and in its internal strategic plan. However, recent remodelling work has seen adjustments made to increase Horowhenua’s population projections, its housing demands, and employment and economic growth forecasts. These projections were lifted to better reflect: > the Wellington Northern Corridor, one of the Roads of National Significance (RoNS), whose completion is expected after 2024; Period of assessment The assessment looked at the current state of the Council and, > anticipated growth of small to medium-sized businesses, with given the changing environment, it also considered the likely Levin promoted as a service centre for the lower North Island; future demands of the community as well as the Council’s needs. and > the increasing attraction of the district for retail, lifestyle, The assessment occurred immediately before the October 2016 housing and retirement. elections, which saw a change of mayor and three new councillors elected (out of a total of 10 councillors). Because of these The Council is currently assessing where and how that growth will changes, an additional interview was conducted with the new occur. -

Waste Disposal Facilities

Waste Disposal Facilities S Russell Landfill ' 0 Ahipara Landfill ° Far North District Council 5 3 Far North District Council Claris Landfill - Auckland City Council Redvale Landfill Waste Management New Zealand Limited Whitford Landfill - Waste Disposal Services Tirohia Landfill - HG Leach & Co. Limited Hampton Downs Landfill - EnviroWaste Services Ltd Waiapu Landfill Gisborne District Council Tokoroa Landfill Burma Road Landfill South Waikato District Council Whakatane District Council Waitomo District Landfill Rotorua District Sanitary Landfill Waitomo District Council Rotorua District Council Broadlands Road Landfill Taupo District Council Colson Road Landfill New Plymouth District Council Ruapehu District Landfill Ruapehu District Council New Zealand Wairoa - Wairoa District Council Waiouru Landfill - New Zealand Defence Force Chatham Omarunui Landfill Hastings District Council Islands Bonny Glenn Midwest Disposal Limited Central Hawke's Bay District Landfill S ' Central Hawke's Bay District Council 0 ° 0 4 Levin Landfill Pongaroa Landfill Seafloor data provided by NIWA Horowhenua District Council Tararua District Council Eves Valley Landfill Tasman District Council Spicer Valley Eketahuna Landfill Porirua City Council Silverstream Landfill Tararua District Council Karamea Refuse Tip Hutt City Council Buller District Council Wainuiomata Landfill - Hutt City Council Southern Landfill - Wellington City Council York Valley Landfill Marlborough Regional Landfill (Bluegums) Nelson City Council Marlborough District Council Maruia / Springs -

Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop

Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop Eric B. Spurr Landcare Research C. John Ralph US Forest Service Landcare Research Science Series No. 32 Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop Eric B. Spurr Landcare Research C. John Ralph US Forest Service (Compilers) Landcare Research Science Series No. 32 Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2006 © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2006 This information may be copied or reproduced electronically and distributed to others without limitation, provided Landcare Research New Zealand Limited is acknowledged as the source of information. Under no circumstances may a charge be made for this information without the express permission of Landcare Research New Zealand Limited. CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Spurr, E.B. Development of bird population monitoring in New Zealand: proceedings of a workshop / Eric B. Spurr and C. John Ralph, compilers – Lincoln, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua Press, 2006. (Landcare Research Science series, ISSN 1172-269X; no. 32) ISBN-13: 978-0-478-09384-1 ISBN-10: 0-478-09384-5 1. Bird populations – New Zealand. 2. Birds – Monitoring – New Zealand. 3. Birds – Counting – New Zealand. I. Spurr, E.B. II. Series. UDC 598.2(931):574.3.087.001.42 Edited by Christine Bezar Layout design Typesetting by Wendy Weller Cover design by Anouk Wanrooy Published by Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research, PO Box 40, Lincoln 7640, New Zealand. 3 Contents Summary ..............................................................................................................................4 -

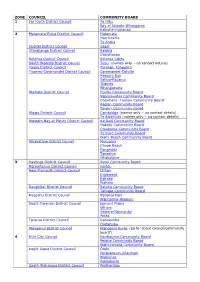

CB List by Zone and Council

ZONE COUNCIL COMMUNITY BOARD 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay of Islands-Whangaroa Kaikohe-Hokianga 2 Matamata-Piako District Council Matamata Morrinsville Te Aroha Opotiki District Council Coast Otorohanga District Council Kawhia Otorohanga Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes South Waikato District Council Tirau (names only – no contact details) Taupo District Council Turangi- Tongariro Thames-Coromandel District Council Coromandel-Colville Mercury Bay Tairua-Pauanui Thames Whangamata Waikato District Council Huntly Community Board Ngaruawahia Community Board Onewhero -Tuakau Community Board Raglan Community Board Taupiri Community Board Waipa District Council Cambridge (names only – no contact details) Te Awamutu (names only – no contact details) Western Bay of Plenty District Council Katikati Community Board Maketu Community Board Omokoroa Community Board Te Puke Community Board Waihi Beach Community Board Whakatane District Council Murupara Ohope Beach Rangitaiki Taneatua Whakatane 3 Hastings District Council Rural Community Board Horowhenua District Council Foxton New Plymouth District Council Clifton Inglewood Kaitake Waitara Rangitikei District Council Ratana Community Board Taihape Community Board Ruapehu District Council National Park Waimarino-Waiouru South Taranaki District Council Egmont Plains Eltham Hawera-Normanby Patea Tararua District Council Dannevirke Eketahuna Wanganui District Council Wanganui Rural (go to ‘about council/community board’) 4 Hutt City Council Eastbourne Community Board Petone Community Board -

Quickstats About Horowhenua District

QuickStats About Horowhenua District Horowhenua District Population/ Dwellings Number of people counted Total population • 29,865 people usually live in Horowhenua District. This is an increase of 42 people, or 0.1 percent, since the 2001 Census. • Its population ranks 39th in size out of the 73 districts in New Zealand. • Horowhenua District has 0.7 percent of New Zealand's population. Population of Horowhenua District and New Zealand, 2006 Census Region/City/District New Zealand Male 14,301 1,965,621 Female 15,564 2,062,329 Total 29,868 4,027,947 Māori ethnic population • 6,078 Māori usually live in Horowhenua District, an increase of 282 people, or 4.9 percent, since the 2001 Census. • Its Māori population ranks 30th in size out of the 73 districts in New Zealand. • 1.1 percent of New Zealand's Māori population usually live in Horowhenua District. Horowhenua District Māori Population of Horowhenua District and New Zealand, 2006 Census Region/City/District New Zealand Male 2,910 274,860 Female 3,165 290,469 Total 6,075 565,329 Note: The Māori ethnic population is the count for people of the Māori ethnic group. It includes those people who stated Māori as being either their sole ethnic group or one of several ethnic groups. Number of dwellings counted • There are 12,027 occupied dwellings and 2,181 unoccupied dwellings in Horowhenua District. • For New Zealand as a whole, there are 1,478,709 occupied dwellings and 159,273 unoccupied dwellings. • There are 111 dwellings under construction in Horowhenua District, compared with 13,557 under construction throughout New Zealand. -

Horowhenua Health and Wellbeing Plan

Horowhenua Te Mahere Hauora Health and Wellbeing Plan 2018-2023 He Mihi Greetings Kua hau mai te rongo he ao hou kei te waihangatia e tātou. Arā, he ao hou e noho nei ko te tangata e tino ora ana, ko te hauora te tino aronga, ko te whai whakaaro o tētahi ki tētahi, ahakoa ko wai, ahakoa nō hea. Nau mai e hika mā ki tēnei whakaaro kua marara ki ngā tōpito katoa o Horowhenua. Nei te mihi kau ake o Te Pae Hauora o Ruahine o Tararua. Ka tukua ko ngā waiora o ngā wai kaukau e kawe atu i ēnei kupu ki ngā kāinga katoa o Horowhenua. The word is out there a new world being created. A new world where everyone is very healthy and health is the focus, along with thoughtful to each other, regardless of who or where we are from. So welcome to this new perspective being dispersed to all corners of the Horowhenua district. This is an unconditional greeting from Te Pae Hauora o Ruahine o Tararua. Let us leave it the healthy waters of bathed by the ancestors to convey these words to all homes of Horowhenua. He Kupu Whakataki Foreword To achieve Quality Living – Healthy Lives – Well Communities we need to think and work differently. We want nothing but the best health care, and the best health and wellbeing for everyone. Every day in our communities people face a range of challenges; some live with mental illness, some live with a chronic disease, others may become acutely unwell and need emergency care. -

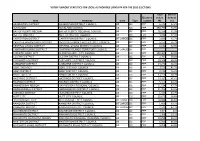

Voter Turnout Statistics for Local Authorities Using Fpp for the 2013 Elections

VOTER TURNOUT STATISTICS FOR LOCAL AUTHORITIES USING FPP FOR THE 2013 ELECTIONS Total Overall Electoral voters turnout Area Authority ward Type system (N) (%) ASHBURTON DISTRICT ASHBURTON DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 6,810 53.3% AUCKLAND AUCKLAND COUNCIL All CC FPP 292,790 34.9% BAY OF PLENTY REGION BAY OF PLENTY REGIONAL COUNCIL All RC FPP 78,938 41.0% BULLER DISTRICT BULLER DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 3,694 62.4% CARTERTON DISTRICT CARTERTON DISTRICT COUNCIL AT LARGE DC FPP 2,880 45.7% CENTRAL HAWKE'S BAY DISTRICT CENTRAL HAWKE'S BAY DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 5,151 55.2% CENTRAL OTAGO DISTRICT CENTRAL OTAGO DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 6,722 52.9% CHATHAM ISLANDS DISTRICT CHATHAM ISLANDS TERRITORY COUNCIL AT LARGE DC FPP CHRISTCHURCH CITY CHRISTCHURCH CITY COUNCIL All CC FPP 103,467 42.9% CLUTHA DISTRICT CLUTHA DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 2,707 59.8% FAR NORTH DISTRICT FAR NORTH DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 18,308 48.9% GISBORNE DISTRICT GISBORNE DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 14,272 48.3% GORE DISTRICT GORE DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 3720 41.7% GREY DISTRICT GREY DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 3,193 45.3% HAMILTON CITY HAMILTON CITY COUNCIL All CC FPP 37,276 38.3% HASTINGS DISTRICT HASTINGS DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 19,927 47.8% HAURAKI DISTRICT HAURAKI DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 5,375 40.4% HAWKE'S BAY REGION HAWKE'S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL All RC FPP 51,524 47.7% HOROWHENUA DISTRICT HOROWHENUA DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 11,700 52.9% HURUNUI DISTRICT HURUNUI DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 1,327 44.7% HUTT CITY HUTT CITY COUNCIL All CC FPP -

Brief of Evidence of Robert Charles Nixon for the Catholic Bishop Of

Before the Independent Hearings Panel In the Matter of the Resource Management Act 1991 And In the Matter of the Canterbury Earthquake (Christchurch Replacement District Plan) Order 2014 And In the Matter of the Proposed Christchurch Replacement Plan (Chapter 21 – Special Purpose (School) Zone) Brief of evidence of Robert Charles Nixon for the Catholic Bishop of Christchurch (submitter 656), Integrated State Schools (submitter 676), the Catholic Diocese and others (submitter 2147), and the Catholic Bishop of Christchurch (submitter 2089). Dated: 14 October 2015 1 INTRODUCTION Qualifications and experience 1. My name is Robert Charles Nixon. I am a Director with Planz Consultants Limited, a planning consultancy based in Christchurch. 2. I hold a Diploma in Town Planning from Auckland University and am consultant planner and an accredited Commissioner. I have been employed in the practice of Planning and Resource Management for 37 years. 3. I have previously worked for the Housing Corporation and the former Ministry of Works, and then the former Paparua County Council and the Selwyn District Council between 1986 and 1991. In 1991 I joined the Christchurch City Council (“the Council”) as Team Leader City Plan. In 2002 I left the Council to join Planit Associates (now Planz Consultants). 4. My experience as Team Leader (City Plan) included both policy and rule development for the Operative Christchurch City Plan (“the Operative Plan”). 5. As a Commissioner, my experience includes hearing and making decisions on numerous plan changes and resource consent applications in the South Island and in Horowhenua District. As part of this role, I have been engaged by both regional and district councils. -

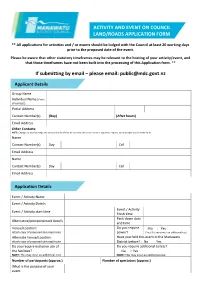

Activity and Event on Council Land/Roads Application Form

ACTIVITY AND EVENT ON COUNCIL LAND/ROADS APPLICATION FORM ** All applications for activities and / or events should be lodged with the Council at least 20 working days prior to the proposed date of the event. Please be aware that other statutory timeframes may be relevant to the hosting of your activity/event, and that those timeframes have not been built into the processing of this Application form. ** If submitting by email – please email: [email protected] Applicant Details Group Name Individual Name (Point of contact) Postal Address Contact Number(s) (Day) (After hours) Email Address Other Contacts: NOTE: Changes to your bookings and contact details will not be actioned unless we receive a legitimate request by the people stated on this form. Name Contact Number(s) Day Cell Email Address Name Contact Number(s) Day Cell Email Address Application Details Event / Activity Name Event / Activity Date/s Event / Activity Event / Activity start time finish time Pack-down date Alternative/postponement date/s and time Venue/Location: Do you require No Yes attach copy of proposed site map/route power? If yes this may incur an additional cost. Have you held this event in the Manawatu Alternate Venue/Location: attach copy of proposed site map/route District before? No Yes Do you require exclusive use of Do you require additional toilets? the facilities? No Yes NOTE: This may incur an additional cost. NOTE: This may incur an additional cost. Number of participants (approx.) Number of spectators (approx.) What is the purpose of your event