Story of the European Anthem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palestine and Poland; a Personal Perspective

1 Nationalism in Comparison: Palestine and Poland; A Personal Perspective Gregory P. Rabb Professor of Political Science Jamestown Community College INTRODUCTION Defining and understanding nationalism in general can be difficult when done without referencing a particular nation or people. This paper is an attempt to understand nationalism in a comparative perspective as recommended by Benedict Anderson in his work entitled “Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism” (2016). Mr. Anderson also recommends understanding nationalism by focusing on the western hemisphere (or so called “new world”) rather than analyzing nationalism in the context of the so-called “old world” from a Euro-centric perspective. I am no Benedict Anderson, but I hope I met his recommendation by understanding nationalism from a personal perspective which I will explain shortly. NATIONALISM When introducing these concepts to my students I talk about the nation-state as the way in which we have organized the world since the Treaty of Westphalia-a Euro-centric perspective. The state is the government, however that is organized, and the nation is the people who are held together by any one or more of the following characteristics: common language, religion, history, ethnicity, and/or national identity including a commitment to a certain set of values (e.g. the emphasis on individual rights and the Constitution as our civil religion as seen in the US) and symbols (e.g. the monarchy and currency in the UK and the flag in the US). We then discuss the “stresses” from above, below, and beside (without) which may be heralding the end of the so-called nation-state era. -

United Kingdom National Anthems Comprehension

United Kingdom National Anthems Comprehension The National Anthem of the United Kingdom is God Save the Queen. It was first performed as a patriotic song in 1745 but only became known as the National Anthem from the beginning of the 19th Century. God Save the Queen represents the whole of the United Kingdom. However, when England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland compete as separate countries in sporting events, they have other national songs. God Save the Queen God save our gracious Queen! Long live our noble Queen! God save the Queen! Send her victorious, Happy and glorious, Long to reign over us, God save the Queen. Since 2010, England has used the song Jerusalem as their national song at the Commonwealth Games after it won a public poll. The composer, teacher and historian of music Hubert Parry set the short poem ‘And did those feet in ancient time’ by William Blake to his own melody. Jerusalem was written in the Victorian times in the middle of the industrial revolution, a time when many factories were being built and cities were crowded. The words of the song remind people of the beauty of nature and the countryside. It is considered to be England's most popular patriotic song. Page 1 of 5 visit twinkl.com Jerusalem Bring me my bow of burning gold! And did those feet in ancient time Bring me my arrows of desire! Walk upon England's Bring me my spear! mountain green? O clouds, unfold! And was the holy Lamb of God Bring me my chariot of fire! On England's pleasant pastures seen? I will not cease from mental fight, And did the countenance divine Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand, Shine forth upon our clouded hills? Till we have built Jerusalem And was Jerusalem builded here In England's green and In England's green and pleasant land. -

University of Copenhagen Faculty Or Humanities

Moving Archives Agency, emotions and visual memories of industrialization in Greenland Jørgensen, Anne Mette Publication date: 2017 Document version Other version Document license: CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Jørgensen, A. M. (2017). Moving Archives: Agency, emotions and visual memories of industrialization in Greenland. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 08. Apr. 2020 UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN FACULTY OR HUMANITIES PhD Thesis Anne Mette Jørgensen Moving Archives. Agency, emotions and visual memories of industrialization in Greenland Supervisor: Associate Professor Ph.D. Kirsten Thisted Submitted on: 15 February 2017 Name of department: Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies Name of department: Minority Studies Section Author(s): Anne Mette Jørgensen Title and subtitle: Moving Archives. Agency, emotions and visual memories of industrialization in Greenland Topic description: Memory, emotion, agency, history, visual anthropology, methodology, museums, post-colonialism, Greenland Supervisor: Kirsten Thisted Submitted on: 15 February 2017 Cover photography: A table during a photo elicitation interview, Ilulissat April 2015 ©AMJørgensen 2 CONTENTS Pre-face 5 Abstract 7 Resumé in Danish 8 1. Introduction 9 a. Aim and argument 9 b. Research questions 13 c. Analytical framework 13 d. Moving archives - Methodological engagements 16 e. The process 18 f. Outline of the Thesis 23 2. Contexts 27 a. Themes, times, spaces 27 b. Industrialization in Greenland 28 c. Colonial and postcolonial archives and museums 40 d. Industrialization in the Disko Bay Area 52 3. Conceptualizing Memory as Moving Archives 60 a. Analytical framework: Memory, agency and emotion 61 b. Memory as agency 62 c. Memory as practice 65 d. Memory as emotion 67 e. -

Estonia Today Estonia’S Blue-Black-White Tricolour Flag 120

Fact Sheet June 2004 Estonia Today Estonia’s Blue-Black-White Tricolour Flag 120 The year of the Estonian National Flag was declared at the 84th celebration of the signing of the Tartu Peace Treaty. The declaration was made by President Arnold Rüütel, Chairman of the Riigikogu Ene Ergma, Prime Minister Juhan Parts. 4 June 2004 will mark 120 years since the blessing of the tricolour in Otepää. 2004 is the official year of the Estonian National Flag and 4 June is now an official National Holiday, National Flag Day. The blue-black-white tricolour has been adopted by Following the occupation of Estonia by Soviet forces the Estonian people, and has become the most in 1940, Estonia’s national symbols were forcibly important and loved national symbol. The tricolour replaced by Soviet symbols. The raising of the has been one of the most important factors in the Estonian flag or even the possession of the tricolour independence, consciousness and solidarity of the was considered a crime for which some people were Estonian people. even sent to prison camps or killed. Expatriate Estonian organisations and societies must be The idea of the blue-black-white colour combination commended for upholding the honour of the Estonian was born from the Estonian Awakening Period at the National Flag during the difficult period of Soviet founding of the “Vironia” Society (now Eesti occupation. The 100th anniversary of the Estonian Üliõpilaste Selts, Estonian Students Society) on Flag was celebrated in exile. The Singing Revolution 29 September 1881. of the late 1980s paved the way for the raising of the The first blue-black-white flag was made in the spring blue-black-white Estonian flag to the top of the Pikk of 1884. -

My Country, 'Tis of Thee Introduction

1 My Country, ’Tis of Thee Introduction Samuel Francis Smith was a twenty-four-year-old Baptist seminary student in Massachusetts when he wrote the lyrics of “America (My Country, ’Tis of Thee),” the patriotic song that would serve as an unofficial national anthem for nearly one-hundred years. In 1831, while studying at Andover Theological Seminary, Smith was asked by composer Lowell Mason to translate some German song books. Inspired by one of the German songs— “God Bless Our Native Land” (set to the tune of “God Save the King”)—Smith set out to write an original patriotic song for America set to the same melody. The result was what Smith called “America” and what would eventually be better known as “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.” The song was first performed on July 4, 1831, by a children’s choir in Boston. Smith’s lyrics invoked the history of America—“Land where my fathers died, / Land of the Pilgrims’ Pride, / From every mountain side / Let freedom ring”—as well as its beauty and sense of itself as a blessed land—“I love thy rocks and rills, / Thy woods and templed hills, / My heart with rapture thrills, / Like that above.” “America” soon took on a life of its own, quickly becoming widely known and well loved, and the song served as an unofficial national anthem until the adoption of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in 1931. In 1864, in the midst of the Civil War, Smith sent a copy of the song to former US Representative J. Wiley Edmands of Massachusetts. -

Poland's Constitution of 1997

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 constituteproject.org Poland's Constitution of 1997 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 Table of contents Preamble . 3 Chapter I: The Republic . 3 Chapter II: The Freedoms, Rights, and Obligations of Citizens . 7 Chapter III: Sources of Law . 17 Chapter IV: The Sejm and The Senate . 19 Chapter V: The President of the Republic of Poland . 26 Chapter VI: The Council of Ministers and Government Administration . 32 Chapter VII: Local Government . 36 Chapter VIII: Courts and Tribunals . 38 Chapter IX: Organs of State Control and For Defence of Rights . 44 Chapter X: Public Finances . 47 Chapter XI: Extraordinary Measures . 49 Chapter XII: Amending the Constitution . 51 Chapter XIII: Final and Transitional Provisions . 52 Poland 1997 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 • Motives for writing constitution • Preamble Preamble Having regard for the existence and future of our Homeland, Which recovered, in 1989, the possibility of a sovereign and democratic determination of its fate, We, the Polish Nation -all citizens of the Republic, • God or other deities Both those who believe in God as the source of truth, justice, good and beauty, As well as those not sharing such faith but respecting those universal values as arising from other sources, Equal in rights and obligations towards the common good -

The European Union Symbols and Their Adoption by the European Parliament

The European Union Symbols and their Adoption by the European Parliament Standard Note: SN/IA/4874 Last updated: 22 October 2008 Author: Vaughne Miller Section International Affairs and Defence Section This Note considers the symbols traditionally used by the European Union institutions and the recent formal adoption of them by the European Parliament. This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. It should not be relied upon as being up to date; the law or policies may have changed since it was last updated; and it should not be relied upon as legal or professional advice or as a substitute for it. A suitably qualified professional should be consulted if specific advice or information is required. This information is provided subject to our general terms and conditions which are available online or may be provided on request in hard copy. Authors are available to discuss the content of this briefing with Members and their staff, but not with the general public. Contents 1 The Symbols of the EU 3 1.1 Flag 3 1.2 Anthem 4 1.3 Europe Day 4 1.4 Motto 5 1.5 Euro 5 2 Attempts to formalise the symbols through Treaty change 6 2.1 The Treaty Establishing a Constitution for Europe 6 2.2 The Treaty of Lisbon 6 3 European Parliament amendment to Rules of Procedure 7 3.1 Constitutional Affairs Committee report 7 3.2 The Plenary adopts the symbols 7 4 Implications and reaction 9 2 1 The Symbols of the EU The process for the adoption of the EU single currency in three stages was enshrined in the 1991 Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty), although the aim of economic and monetary union (EMU) had been acknowledged at the 1969 European Council summit at The Hague.1 The EU flag, anthem and Europe Day were adopted by the European Council in Milan in 1985, while the “United in Diversity” motto was adopted in 2000. -

National Anthem

National Anthem The Star Spangled Banner Oh, say! can you see by the dawn's early light What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming; Whose broad stripes and bright stars, through the perilous fight, O'er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming, And the rocket's red glare, the bombs bursting in air, Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there: Oh, say! does that star-spangled banner yet wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave? On the shore, dimly seen through the mists of the deep, Where the foe's haughty host in dread silence reposes, What is that which the breeze, o'er the towering steep, As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses; Now it catches the gleam of the morning's first beam, In fully glory reflected now shines in the stream: 'Tis the star-spangled banner! Oh, long may it wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! And where is that band who so vauntingly swore That the havoc of war and the battle's confusion A home and a country should leave us no more, Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps' pollution; No refuge could save the hireling and slave From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave: And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! Oh, thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand Between their loved home and the war's desolation! Blest with victory and peace, may the heav'n-rescued land Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation; Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, And this be our motto: "In God is our trust." And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! The Star-Spangled Banner" The lyrics come from a poem written in 1814 by Francis Scott Key. -

Pages on Dionysios Solomos Moderngreek.Qxd 19-11-02 2:15 Page 2

ModernGreek.qxd 19-11-02 2:15 Page 1 MODERN GREEK STUDIES (AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND) Volume 10, 2002 A Journal for Greek Letters Pages on Dionysios Solomos ModernGreek.qxd 19-11-02 2:15 Page 2 Published by Brandl & Schlesinger Pty Ltd PO Box 127 Blackheath NSW 2785 Tel (02) 4787 5848 Fax (02) 4787 5672 for the Modern Greek Studies Association of Australia and New Zealand (MGSAANZ) Department of Modern Greek University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia Tel (02) 9351 7252 Fax (02) 9351 3543 E-mail: [email protected] ISSN 1039-2831 Copyright in each contribution to this journal belongs to its author. © 2002, Modern Greek Studies Association of Australia All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Typeset and design by Andras Berkes Printed by Southwood Press, Australia ModernGreek.qxd 19-11-02 2:15 Page 3 MODERN GREEK STUDIES ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND (MGSAANZ) ETAIREIA NEOELLHNIKWN SPOUDWN AUSTRALIAS KAI NEAS ZHLANDIAS President: Vrasidas Karalis, University of Sydney, Sydney Vice-President: Maria Herodotou, La Trobe University, Melbourne Secretery: Chris Fifis, La Trobe University, Melbourne Treasurer: Panayota Nazou, University of Sydney, Sydney Members: George Frazis (Adelaide), Elizabeth Kefallinos (Sydney), Andreas Liarakos (Melbourne), Mimis Sophocleous (Melbourne), Michael Tsianikas (Adelaide) MGSAANZ was founded in 1990 as a professional association by those in Australia and New Zealand engaged in Modern Greek Studies. Membership is open to all interested in any area of Greek studies (history, literature, culture, tradition, economy, gender studies, sexualities, linguistics, cinema, Diaspora, etc). -

European National Anthems United Kingdom Europe Is One of the Seven Continents of the World

European National Anthems United Kingdom Europe is one of the seven continents of the world. All the different countries in Europe have their own national anthem. A national anthem can be a fanfare, a hymn, a march or a song. The British national anthem, God Save The Queen, is one of the oldest national anthems, having been performed since 1745. God Save The Queen God save our gracious Queen! Long live our noble Queen! God save the Queen! Send her victorious, Happy and glorious, Long to reign over us, God save the Queen. France La Marseillaise La Marseillaise is the French national Arise you children of anthem. The text opposite has been the fatherland translated from the original, which is The day of glory has arrived in French. It was composed in just one night Against us tyranny on April 24, 1792 during the French Has raised its bloodied banner Revolution by Claude-Joseph Rouget Do you hear in the fields de Lisle. The howling of these The words of the anthem are intended to fearsome soldiers? inspire soldiers to defend their country They are coming into your in War. midst Marseille is a place in France where the To slit the throats of your sons soldiers were fighting when the anthem and wives! was written. To arms, citizens, Form your battalions, Let us march, let us march! May impure blood Soak our fields’ furrows! Spain The Marcha Real is the national anthem of Spain. In English, the title means ‘The Royal March’. The anthem has no words. It is a melody played by an orchestra. -

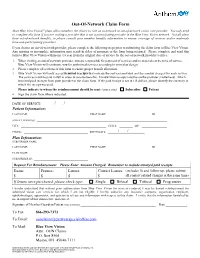

Out-Of-Network Claim Form /

Out-Of-Network Claim Form Most Blue View VisionSM plans allow members the choice to visit an in-network or out-of-network vision care provider. You only need to complete this form if you are visiting a provider that is not a participating provider in the Blue View Vision network. Not all plans have out-of-network benefits, so please consult your member benefits information to ensure coverage of services and/or materials from non-participating providers. If you choose an out-of-network provider, please complete the following steps prior to submitting the claim form to Blue View Vision. Any missing or incomplete information may result in delay of payment or the form being returned. Please complete and send this form to Blue View Vision within one (1) year from the original date of service by the out-of-network provider’s office. 1. When visiting an out-of-network provider, you are responsible for payment of services and/or materials at the time of service. Blue View Vision will reimburse you for authorized services according to your plan design. 2. Please complete all sections of this form to ensure proper benefit allocation. 3. Blue View Vision will only accept itemized receipts that indicate the services provided and the amount charged for each service. The services must be paid in full in order to receive benefits. Handwritten receipts must be on the provider’s letterhead. Attach itemized paid receipts from your provider to the claim form. If the paid receipt is not in US dollars, please identify the currency in which the receipt was paid. -

Eesti Voldik Inglise Keelne.Indd

E S T O N I A Look and you will see! Estonia Estonia • facts • national symbols • anthem • miscellaneous • Estonia is like a wild strawberry: small, pristine, diffi cult to fi nd… and those who don’t know how to, fail to recognise and “ value it. But once we possess it, once it’s ours, then it’s one of the best things of all.” Toomas Hendrik Ilves, President of the Republic of Estonia Offi cial name: Republic of Estonia Currency: Euro (EUR) Anthem: Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm Flag: Blue-black-and-white /My Fatherland, My Happiness and Joy/ National bird: Barn swallow (Fredrik Pacius) National fl ower:C o r n fl o w e r Capital: Tallinn Number of islands: 1521 Area: 45,227 km2 Highest point: Population: 1,311,870 Suur Munamägi / Offi cial language: Estonian Great Egg Hill/, 318 m Head of state: President Toomas Hendrik Ilves Member of NATO, EU, UN, System of government: Parliamentary republic OSCE, OECD & WTO National day: 24 February (Independence Day, 1918) See more: www.eesti.ee https://twitter.com/IlvesToomas www.estonia.eu www.valitsus.ee https://www.facebook.com/eesti.ee www.tallinn.ee http://xgis.maaamet.ee/xGIS/XGis www.estonianworld.com www.president.ee What COUNTRY is this? What country is this? There are no mountains, just endless forests and swamps. “ But the people here are full of magic power and their songs are mysterious.” Peeter Volkonski, musician, actor and poet Th e population of Estonia is a little over a million – roughly as much as in cities like Milan, Dallas or Munich.