James Giglio on One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 01, 1962 Cable No. 341 from the Czechoslovak Embassy in Havana (Pavlíček)

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified November 01, 1962 Cable no. 341 from the Czechoslovak Embassy in Havana (Pavlíček) Citation: “Cable no. 341 from the Czechoslovak Embassy in Havana (Pavlíček),” November 01, 1962, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, National Archive, Archive of the CC CPCz, (Prague); File: “Antonín Novotný, Kuba,” Box 122. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115229 Summary: Pavlicek relays to Prague the results of the meeting between Cuban foreign minister Raul Roa and UN Secretary General U Thant. Thant expressed sympathy for the Cuban people and acknowledged the right for Cuba to submit their considerations for the resolution to the crisis. The Cuban requests included lifting the American blockade, fulfilling Castro's 5 Points, and no UN inspection of the missile bases. Besides the meeting with the Secretary General, Pavlicek also recounts the meeting of a Latin American delegation including representatives from Brazil, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay and Mexico. All nations but Mexico refused to give in to U.S. pressures, and stood in support of Cuba. Pavlicek then moves on to cover the possible subjects of Castro's speech on 1 November, including the Cuban detention of anticommunist groups in country and the results of the negotiations with U Thant. In the meantime, the Cuban government is concerned with curtailing the actions of anti-Soviet groups ... Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Czech Contents: English Translation Telegram from Havana File # 11.337 St Arrived: 1.11.62 19:35 Processed: 2.11.62 01:00 Office of the President, G, Ku Dispatched: 2.11.62 06:45 NEWSFLASH! [Cuban Foreign Minister Raúl] Roa informed me of the results of the talks with [UN Secretary- General] U Thant. -

E Struggle Against Communism Lasted Longer Than All of America's Other Wars Put Together

e struggle against Communism lasted longer than all of America's other wars put together. 1 «04 APP 40640111114- AO' • m scorting a u-95 - Bear" bomber down the Atlantic Coast was a fairly ommon Cold War mission and illustrates how close the Soviet Union and the US often came to a direct confrontation. Come say the Cold War began even It7 before the end of World War II, but Soviet leader Joseph Stalin officially initiated it when he attacked his wartime Allies in a speech in February 1946. Thp next month at Westminster College, Fulton, Mo., Winston S. Churchill, former British Prime Minister, made his "Iron Curtain" speech, noting that all the eastern European capitals were now in Soviet hands. The US Army Air Forces r had demobilized much of its World War II strength even as Moscow provoked Communist Party take-overs in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia in 1947 and 1948. Emboldened, the USSR began a blockade of the Western- controlled sectors of Berlin in spring 1948, intending to drive out the Allies. The newly independent US Air Force countered with a massive airlift of food and supplies into Berlin. C-54 Skymasters like the one at left earned their fame handling this mission. The Soviet Union conceded failure in May 1949, and a C-54 crew made the Berlin Airlift's last flight on September 30, 1949. In the following decades, conflicts flared between the USSR and satellite countries. In this 1968 photo, Czechs carry a comrade wounded in Prague during the Soviet invasion to crush Alexander Dubcek's attempt at reform. -

'The Cuban Question' and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964

‘The Cuban question’ and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964 LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101153/ Version: Published Version Article: Harmer, Tanya (2019) ‘The Cuban question’ and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964. Journal of Cold War Studies, 21 (3). pp. 114-151. ISSN 1520-3972 https://doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00896 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ The “Cuban Question” and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959–1964 ✣ Tanya Harmer In January 1962, Latin American foreign ministers and U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk arrived at the Uruguayan beach resort of Punta del Este to debate Cuba’s position in the Western Hemisphere. Unsurprisingly for a group of representatives from 21 states with varying political, socioeconomic, and geo- graphic contexts, they had divergent goals. Yet, with the exception of Cuba’s delegation, they all agreed on why they were there: Havana’s alignment with “extra-continental communist powers,” along with Fidel Castro’s announce- ment on 1 December 1961 that he was a lifelong Marxist-Leninist, had made Cuba’s government “incompatible with the principles and objectives of the inter-American system.” A Communist offensive in Latin America of “in- creased intensity” also meant “continental unity and the democratic institu- tions of the hemisphere” were “in danger.”1 After agreeing on these points, the assembled officials had to decide what to do about Cuba. -

DM - Cuba 3/4/15 11:19 AM Page V

DM - Cuba 3/4/15 11:19 AM Page v Table of Contents Preface . .ix How to Use This Book . .xiii Research Topics for Defining Moments: The Cuban Missile Crisis . .xv NARRATIVE OVERVIEW Prologue . .3 Chapter 1: The Cold War . .7 Chapter 2: The United States and Cuba . .23 Chapter 3: The Discovery of Soviet Missiles in Cuba . .37 Chapter 4: The World Reaches the Brink of Nuclear War . .53 Chapter 5: The Cold War Comes to an End . .69 Chapter 6: Legacy of the Cuban Missile Crisis . .89 BIOGRAPHIES Rudolf Anderson Jr. (1927-1962) . .105 American Pilot Who Was the Only Combat Casualty of the Cuban Missile Crisis Fidel Castro (1926-) . .110 Premier of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis Anatoly Dobrynin (1919-2010) . .116 Soviet Ambassador to the U.S. during the Cuban Missile Crisis v DM - Cuba 3/4/15 11:19 AM Page vi Defining Moments: The Cuban Missile Crisis Alexander Feklisov (1914-2007) . .120 Russian Spy Who Proposed a Deal to Resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) . .125 President of the United States during the Cuban Missile Crisis Robert F. Kennedy (1925-1968) . .131 U.S. Attorney General and Leader of ExComm Nikita Khrushchev (1891-1971) . .137 Soviet Premier Who Placed Nuclear Missiles in Cuba John McCone (1902-1991) . .144 Director of the CIA during the Cuban Missile Crisis Robert S. McNamara (1916-2009) . .148 U.S. Secretary of Defense during the Cuban Missile Crisis Ted Sorensen (1928-2010) . .153 Special Counsel and Speechwriter for President Kennedy PRIMARY SOURCES The Soviet Union Vows to Defend Cuba . -

Annotated Timeline,” JFK the Last Speech, Mascot Books, 2018, Pp 97-112

Selected Timeline: Kennedy, Frost, and the Amherst College Class of 1964i The focus is on the years 1960-1963 Draft last updated: 13 February 2018 1874 26 Mar Robert Frost was born to William Prescott Frost, Jr., and Isabelle Moodie in San Francisco, CA. 1917 29 May John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK) was born to Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., and Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald in Brookline, MA. 1959 Jan Castro’s revolutionary forces seized power in Cuba, President Batista fled. 26 Mar Press conference prior to Frost’s 85th birthday gala. In response to a question regarding the alleged decline of New England, Frost responded, “The next President of the United States will be from Boston. Does that sound as if New England is decaying? … He’s a Puritan named Kennedy. The only Puritans left these days are the Roman Catholics. There. I guess I wear my politics on my sleeve.” April JFK letter to Frost: “I just want to send you a note to let you know how gratifying it was to be remembered by you on the occasion of your 85th birthday. 1960 1 May Gary Powers’ U2 spy plane was shot down over USSR. Feb Sit-ins by African-Americans at segregated lunch counters began and spread to 65 cities in 12 southern states. 7 May USSR established diplomatic relations with Cuba. 13 Sept An Act of Congress, Public Law P.L. 86-747, 74 Stat. 883, awarded Frost a Congressional Gold Medal, “In recognition of his poetry, which has enriched the culture of the United States and the philosophy of the world.” There apparently was no public award ceremony until JFK took the initiative in March 1962. -

Major Rudolf Anderson Jr., US Air Force Cold War / Cuban Missile Crisis

Major Rudolf Anderson Jr., US Air Force Cold War / Cuban Missile Crisis Major Anderson was the first recipient of the Air Force Cross medal, our Nation’s and the Air Force's second-highest award and decoration for valor. He was our only U.S. fatality by enemy fire during the Cuban Missile Crisis when his aircraft was shot down over Cuba in 1962. Rudolf Anderson, Jr was born in Spartanburg, South Carolina in 1927. Three years after graduation from Clemson University he entered the US Air Force as a pilot. He began his operational career flying RF-86 Sabres and earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses for reconnaissance missions over Korea. After the war in Korea he served with the 15th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron at Kunsan Air Base in South Korea. He then returned home to the US in 1955 to train and qualify in flying the U-2 (Dragon Lady) high altitude reconnaissance aircraft. After qualifying on the U-2 "he became the 4080th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing's top U-2 pilot with over one thousand hours, making him a vital part of the United States' reconnaissance operation over Cuba in October of 1962." On Saturday, October 27, 1962 Major Anderson took off in which would be his sixth mission over Cuba in a U-2F Dragon, from a forward operating location at McCoy Air Force Base in Orlando, Florida. A few hours into his mission, he was shot down by one of two Soviet-supplied S-75 Dvina surface-to-air missiles launched toward his aircraft high over Banes, Cuba. -

Soviet Intelligence and the Cuban Missile Crisis

This article was downloaded by: [Harvard College] On: 18 September 2012, At: 12:38 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Intelligence and National Security Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fint20 Soviet intelligence and the Cuban missile crisis Aleksandr Fursenko a & Timothy Naftali b a Chairman of the Department of History, Russian Academy of Science b Olin Fellow at International Security Studies, Yale University Version of record first published: 02 Jan 2008. To cite this article: Aleksandr Fursenko & Timothy Naftali (1998): Soviet intelligence and the Cuban missile crisis, Intelligence and National Security, 13:3, 64-87 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02684529808432494 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/ terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

The General Assembly, Having Received the Recommendation of the Security Council of 4 October 1962 That the Democratic and Popul

Resolution, adopted without reference to a Committee 71 1754 (XVII). Admission of the Democratic and 1758 (XVII). Admission of Uganda to member Popular Republic of Algeria to membership ship in the United Nations in the United Nations The General Assembly, The General Assembly, Having received the recommendation of the Security Having received the recommendation of the Security Council of 15 October 1962 that Uganda should be Council of 4 October 1962 that the Democratic and admitted to membership in the United Nations,12 Popular Republic of Algeria should be admitted to Having considered the application for membership membership in the United Nations,10 of Uganda,13 Having considered the application for membership Decides to admit Uganda to membership in the of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria,11 United Nations. Decides to admit the Democratic and Popular Re 1158th plenary meeting, public of Algeria to membership in the United Nations. 25 October 1962. 1146th plenary meeting, 1759 (XVII). Report of the Commission of in 8 October 1962. vestigation into the conditions and circum stances resulting in the tragic death of 1756 (XVII). Report of the Committee on ar• Mr. Dag Hammarskjold and of members rangements for a conference for the purpose of the party accompanying him of reviewing the Charter The General Assembly, The General Assembly, Recalling its resolution 1628 (XVI) of 26 October Recalling the provisions of its resolutions 992 (X) 1961 in which it decided to appoint a Commission of five of 21 November 1955, 1136 (XII) of 14 October 1957, eminent persons to carry out an investigation into the 1381 (XIV) of 20 November 1959 and 1670 (XVI) circumstances surrounding the tragic death of Mr. -

The Cuban Missile Crisis and Its Effect on the Course of Détente

1 THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS AND ITS EFFECT ON THE COURSE OF DÉTENTE 2 Abstract The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union began in 1945 with the end of World War II and the start of an international posturing for control of a war-torn Europe. However, the Cold War reached its peak during the events of the Cuban Missile Crisis, occurring on October 15-28, 1962, with the United States and the Soviet Union taking sides against each other in the interest of promoting their own national security. During this period, the Soviet Union attempted to address the issue of its own deficit of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles compared to the United States by placing shorter-range nuclear missiles within Cuba, an allied Communist nation directly off the shores of the United States. This move allowed the Soviet Union to reach many of the United States’ largest population centers with nuclear weapons, placing both nations on a more equal footing in terms of security and status. The crisis was resolved through the imposition of a blockade by the United States, but the lasting threat of nuclear destruction remained. The daunting nature of this Crisis led to a period known as détente, which is a period of peace and increased negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union in order to avoid future confrontations. Both nations prospered due to the increased cooperation that came about during this détente, though the United States’ and the Soviet Union’s rapidly changing leadership styles and the diverse personalities of both countries’ individual leaders led to fluctuations in the efficiency and extent of the adoption of détente. -

Cuban Missile Crisis Operations

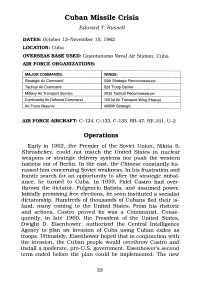

Cuban Missile Crisis Edward T. Russell DATES: October 13-November 15, 1962 LOCATION: Cuba OVERSEAS BASE USED : Guantanamo Naval Air Station, Cuba AIR FORCE ORGANIZATIONS : MAJOR COMMANDS: WINGS: Strategic Air Command 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Tactical Air Command 62d Troop Carrier Military Air Transport Service 363d Tactical Reconnaissance Continental Air Defense Command 1501 st Air Transport Wing (Heavy) Air Force Reserve 4080th Strategic AIR FORCE AIRCRAFT: C-124, C-133, C-135, RB-47, RF-101, U-2 Operations Early in 1962, the Premier of the Soviet Union, Nikita S . Khrushchev, could not match the United States in nuclear weapons or strategic delivery systems nor push the western nations out of Berlin. In the east, the Chinese constantly ha- rassed him concerning Soviet weakness. In his frustration and frantic search for an opportunity to alter the strategic imbal- ance, he turned to Cuba . In 1959, Fidel Castro had over- thrown the dictator, Fulgencio Batista, and assumed power. Initially promising free elections, he soon instituted a socialist dictatorship . Hundreds of thousands of Cubans fled their is- land, many coming to the United States . From his rhetoric and actions, Castro proved he was a Communist. Conse- quently, in late 1960, the President of the United States, Dwight D . Eisenhower, authorized the Central Intelligence Agency to plan an invasion of Cuba using Cuban exiles as troops . Ultimately, Eisenhower hoped that in conjunction with the invasion, the Cuban people would overthrow Castro and install a moderate, pro-U.S . government. Eisenhower's second term ended before the plan could be implemented . The new 33 SHORT OF WAR president, John F. -

Appointment Books Series

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS EISENHOWER, DWIGHT D.: Papers, Post-Presidential, 1961-69 DDE APPOINTMENT BOOKS SERIES SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE The DDE Appointment Books Series consists of 1,400 pages which cover the period from April 1961 to May 1968. This series includes seven appointment volumes dated 1961, 1962-63, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967 and 1968, and is arranged chronologically. Ms. Lillian “Rusty” Brown apparently prepared most of these appointment records when she served as President Eisenhower’s confidential secretary from October 1962 to October 1967. The earlier, less detailed entries were presumably maintained by Mrs. Ann C. Whitman, who served as President Eisenhower’s secretary during 1961 and early 1962. Literary property rights in these papers are retained by President Eisenhower’s son, John S.D. Eisenhower. The appointment book dated 1961 consists entirely of printed appointment schedules with intermittent pencilled entries. It includes a few typed lists for 1962, the only items found in this series for that year. The second volume, although dated 1962-63, consists entirely of entries recorded during 1963. Pages for the first four months of the year bear sketchy typed or handwritten annotations. Beginning in May, however, more detailed appointment schedules were prepared. These sometimes list not only individuals meeting with President Eisenhower but also topics discussed as well. A few summaries of conversations also appear among the 1963 entries. The volume dated 1964 is the most detailed of the appointment books and includes summaries of numerous conversations as well as appointment schedules. It constitutes an important source of information on General Eisenhower’s participation in the 1964 presidential campaign. -

Cold War Continues 1960'S Or Cuban Missile Crisis C.Notes

Cold War Continues 1960’s or Cuban Missile Crisis C.notes Cold War Continues 1960’s or Cuban Missile Crisis C.notes Fidel Castro and Cuba Fidel Castro and Cuba • After assuming power in 1959, Fidel Castro transformed • After assuming power in 1959, Fidel Castro transformed Cuba into the first communist state in the Western Cuba into the first communist state in the Western Hemisphere Hemisphere • Bay of Pigs April 1961 • Bay of Pigs April 1961 – ex·pa·tri·ate - give up residence in one’s homeland – ex·pa·tri·ate - give up residence in one’s homeland and denounce allegiance to them and denounce allegiance to them – Take notes during clip – Take notes during clip http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qXZp8bxpNY : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qXZp8bxpNY : summarize Bay of Pigs I.N. top ½ page 68 summarize Bay of Pigs I.N. top ½ page 68 Cubam Missile Crisis Cubam Missile Crisis * October 1962, U.S. U-2 spy plane secretly photographed nuclear * October 1962, U.S. U-2 spy plane secretly photographed nuclear missile sites being built by the Soviet Union on the island of Cuba. missile sites being built by the Soviet Union on the island of Cuba. 13 days in Oct. on the brink of nuclear war 13 days in Oct. on the brink of nuclear war “On the 8th day of the crisis, October 24, 1962, The U.S. has set up a “On the 8th day of the crisis, October 24, 1962, The U.S. has set up a naval blockade around Cuba.