Cuban Missile Crisis Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 01, 1962 Cable No. 341 from the Czechoslovak Embassy in Havana (Pavlíček)

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified November 01, 1962 Cable no. 341 from the Czechoslovak Embassy in Havana (Pavlíček) Citation: “Cable no. 341 from the Czechoslovak Embassy in Havana (Pavlíček),” November 01, 1962, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, National Archive, Archive of the CC CPCz, (Prague); File: “Antonín Novotný, Kuba,” Box 122. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115229 Summary: Pavlicek relays to Prague the results of the meeting between Cuban foreign minister Raul Roa and UN Secretary General U Thant. Thant expressed sympathy for the Cuban people and acknowledged the right for Cuba to submit their considerations for the resolution to the crisis. The Cuban requests included lifting the American blockade, fulfilling Castro's 5 Points, and no UN inspection of the missile bases. Besides the meeting with the Secretary General, Pavlicek also recounts the meeting of a Latin American delegation including representatives from Brazil, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay and Mexico. All nations but Mexico refused to give in to U.S. pressures, and stood in support of Cuba. Pavlicek then moves on to cover the possible subjects of Castro's speech on 1 November, including the Cuban detention of anticommunist groups in country and the results of the negotiations with U Thant. In the meantime, the Cuban government is concerned with curtailing the actions of anti-Soviet groups ... Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Czech Contents: English Translation Telegram from Havana File # 11.337 St Arrived: 1.11.62 19:35 Processed: 2.11.62 01:00 Office of the President, G, Ku Dispatched: 2.11.62 06:45 NEWSFLASH! [Cuban Foreign Minister Raúl] Roa informed me of the results of the talks with [UN Secretary- General] U Thant. -

E Struggle Against Communism Lasted Longer Than All of America's Other Wars Put Together

e struggle against Communism lasted longer than all of America's other wars put together. 1 «04 APP 40640111114- AO' • m scorting a u-95 - Bear" bomber down the Atlantic Coast was a fairly ommon Cold War mission and illustrates how close the Soviet Union and the US often came to a direct confrontation. Come say the Cold War began even It7 before the end of World War II, but Soviet leader Joseph Stalin officially initiated it when he attacked his wartime Allies in a speech in February 1946. Thp next month at Westminster College, Fulton, Mo., Winston S. Churchill, former British Prime Minister, made his "Iron Curtain" speech, noting that all the eastern European capitals were now in Soviet hands. The US Army Air Forces r had demobilized much of its World War II strength even as Moscow provoked Communist Party take-overs in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia in 1947 and 1948. Emboldened, the USSR began a blockade of the Western- controlled sectors of Berlin in spring 1948, intending to drive out the Allies. The newly independent US Air Force countered with a massive airlift of food and supplies into Berlin. C-54 Skymasters like the one at left earned their fame handling this mission. The Soviet Union conceded failure in May 1949, and a C-54 crew made the Berlin Airlift's last flight on September 30, 1949. In the following decades, conflicts flared between the USSR and satellite countries. In this 1968 photo, Czechs carry a comrade wounded in Prague during the Soviet invasion to crush Alexander Dubcek's attempt at reform. -

Almanac, November 1962, Vol. 9, No. 3

Research Grants, Fellowships Management Committee Reports Now Available to Faculty To President's Staff Conference The University's Committee on the Advancement of A four-point program designed to strengthen and sys- Research has announced plans to award ten Summer tematize the methods by which the University recruits and Research Fellowships for 1963. In keeping with University retains administrative staff personnel was submitted this policy of providing more generous support for faculty month to the President's Staff Conference by the newly research, these awards have been increased in number and organized Committee on Management Development. the stipend raised to $1500. The program, which the Conference has asked the Com- Competition for these fellowships is open to all full-time mittee to find means of implementing, contains these members of the faculty who hold a doctorate or its equiva- points: lent. While appointments will be based primarily on the 1. The Committee on Management Development should merit of projects proposed and on the research potential be established as a standing committee. of applicants, preference is given to applications from 2. The Committee should have the responsibility of younger members of the faculty and those from the lower seeing that periodic evaluations are made of the abilities, academic ranks. experience, and performance of the present administrative The committee also has somewhat greater resources for personnel, so that those staff members who show the great- its regular grants in aid of research than it has had in est promise of further development can be identified. recent years. These grants provide for clerical or technical 3. -

The ICRC and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, Le CICR Et La Crise

RICR Juin IRRC June 2001 Vol. 83 No 842 287 The ICRC and the 1962 Cuban missile crisis by Thomas Fischer n 6 November 1962, the Swiss ambassador and former President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Paul Rüegger, embarked on a delicate mission to negotiate with the United Nations OSecretary-General and the representatives of the two superpowers and Cuba in New York. His task was to specify and obtain prior acceptance of the conditions under which the ICRC was prepared to lend its good offices to the United Nations and the parties involved in the Cuban missile crisis, so as to help ease the tension that had arisen from the secret introduction of Soviet nuclear weapons in the Caribbean. This article deals with the unusual role the ICRC was ready to play in that crisis and sheds new light on how it came to be engaged in these highly political matters. New American, Soviet and Cuban sources that have become known since 1990 reveal in great detail the events surround- ing the planned ICRC intervention in the missile crisis. It is a story that has so far remained untold. Most of the new material is to be found in the microfiche collection of declassified documents on the Cuban missile crisis compiled and made available by the National Thomas Fischer is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Political Science, University of Zurich, Switzerland, and a research assistant at the Center for International Studies (CIS), Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich. 288 The ICRC and the 1962 Cuban missile crisis Security Archive, a private research institution in Washington DC.1 The collection also contains the relevant documents of the United Nations Archives in New York. -

The United States, Brazil, and the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 (Part 1)

TheHershberg United States, Brazil, and the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 The United States, Brazil, and the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 (Part 1) ✣ What options did John F. Kennedy consider after his aides in- formed him on 16 October 1962 that the Soviet Union was secretly deploy- ing medium-range nuclear-capable missiles in Cuba? In most accounts, his options fell into three categories: 1. military: an attack against Cuba involving a large-scale air strike against the missile sites, a full-scale invasion, or the ªrst followed by the second; 2. political-military: a naval blockade of Cuba (euphemistically called a “quarantine”) to prevent the shipment of further “offensive” military equipment and allow time to pressure Soviet leader Nikita Khrush- chev into withdrawing the missiles; or 3. diplomatic: a private overture to Moscow to persuade Khrushchev to back down without a public confrontation. Kennedy ultimately chose the second option and announced it on 22 Octo- ber in his nationally televised address. That option and the ªrst (direct mili- tary action against Cuba) have been exhaustively analyzed over the years by Western scholars. Much less attention has been devoted to the third alterna- tive, the diplomatic route. This article shows, however, that a variant of that option—a variant that has never previously received any serious scholarly treatment—was actually adopted by Kennedy at the peak of the crisis. The United States pursued a separate diplomatic track leading not to Moscow but to Havana (via Rio de Janeiro), and not to Khrushchev but to Fidel Castro, in a secret effort to convince the Cuban leader to make a deal: If Castro agreed to end his alliance with Moscow, demand the removal of the Soviet missiles, and disavow any further support for revolutionary subversion in the Western hemisphere, he could expect “many changes” in Washington’s policy toward Journal of Cold War Studies Vol. -

Cuban Missile Crisis: Applying Strategic Culture to Gametheory

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2013 Cuban Missile Crisis: Applying Strategic Culture to Gametheory Chelsea E. Carattini Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Carattini, Chelsea E., "Cuban Missile Crisis: Applying Strategic Culture to Gametheory" (2013). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 236. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/236 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction Game theory applied to political situations offers a unique approach to analyzing and understanding international relations. Yet the rigid structure that lends itself so well to mathematics is not practical in the real world . It lacks a built in mechanism for determining a player's preferences, which is a key part of an international "game" or situation. Strategic culture, another international relations theory, is quite the opposite. Critics claim it suffers from a lack of structure, but it captures the spirit of international actors and what makes them tick. This paper explores the idea of pairing the two otherwise unrelated theories to bolster both in the areas where they are lacking in order to provide a more complete understanding of international states' behavior and motivations. Brief Summary of Major Theories The theories presented in the following pages are drawn from distinct schools of thought; consequently it is necessary to provide some background information. -

Timeline of the Cold War

Timeline of the Cold War 1945 Defeat of Germany and Japan February 4-11: Yalta Conference meeting of FDR, Churchill, Stalin - the 'Big Three' Soviet Union has control of Eastern Europe. The Cold War Begins May 8: VE Day - Victory in Europe. Germany surrenders to the Red Army in Berlin July: Potsdam Conference - Germany was officially partitioned into four zones of occupation. August 6: The United States drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima (20 kiloton bomb 'Little Boy' kills 80,000) August 8: Russia declares war on Japan August 9: The United States drops atomic bomb on Nagasaki (22 kiloton 'Fat Man' kills 70,000) August 14 : Japanese surrender End of World War II August 15: Emperor surrender broadcast - VJ Day 1946 February 9: Stalin hostile speech - communism & capitalism were incompatible March 5 : "Sinews of Peace" Iron Curtain Speech by Winston Churchill - "an "iron curtain" has descended on Europe" March 10: Truman demands Russia leave Iran July 1: Operation Crossroads with Test Able was the first public demonstration of America's atomic arsenal July 25: America's Test Baker - underwater explosion 1947 Containment March 12 : Truman Doctrine - Truman declares active role in Greek Civil War June : Marshall Plan is announced setting a precedent for helping countries combat poverty, disease and malnutrition September 2: Rio Pact - U.S. meet 19 Latin American countries and created a security zone around the hemisphere 1948 Containment February 25 : Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia March 2: Truman's Loyalty Program created to catch Cold War -

The Cuban Missile Crisis: How to Respond?

The Cuban Missile Crisis: How to Respond? Topic: Cuban Missile Crisis Grade Level: Grades 9 – 12 Subject Area: US and World History after World War II; US Government Time Required: 1-2 hours Goals/Rationale: During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy's advisors discussed many options regarding how they might respond to the installation of Soviet missiles in Cuba. In this lesson, students examine primary source documents and recordings to consider some of the options discussed by Kennedy's advisors during this crisis and the rationale for why the president might have selected the path he chose. Essential Question: Does an individual's role in government influence his or her view on how to respond to important issues? Objectives Students will: discuss some of the options considered by Kennedy’s advisors during the Cuban Missile Crisis; identify the governmental role of participants involved in decision making and consider whether or not their role influenced their choice of option(s); consider the ramifications of each option; discuss the additional information that might have been helpful as of October 18, 1962 for Kennedy and his staff to know in order to make the most effective decision. analyze why President Kennedy made the decision to place a naval blockade around Cuba. Connections to Curriculum (Standards) National History Standards US History, Era 9 Standard 2: How the Cold War and conflicts in Korea and Vietnam influenced domestic and international politics. Standard 2A: The student understands the international origins and domestic consequences of the Cold War. Massachusetts History and Social Studies Curriculum Frameworks USII.T5 (1) Using primary sources such as campaign literature and debates, news articles/analyses, editorials, and television coverage, analyze the important policies and events that took place during the presidencies of John F. -

DM - Cuba 3/4/15 11:19 AM Page V

DM - Cuba 3/4/15 11:19 AM Page v Table of Contents Preface . .ix How to Use This Book . .xiii Research Topics for Defining Moments: The Cuban Missile Crisis . .xv NARRATIVE OVERVIEW Prologue . .3 Chapter 1: The Cold War . .7 Chapter 2: The United States and Cuba . .23 Chapter 3: The Discovery of Soviet Missiles in Cuba . .37 Chapter 4: The World Reaches the Brink of Nuclear War . .53 Chapter 5: The Cold War Comes to an End . .69 Chapter 6: Legacy of the Cuban Missile Crisis . .89 BIOGRAPHIES Rudolf Anderson Jr. (1927-1962) . .105 American Pilot Who Was the Only Combat Casualty of the Cuban Missile Crisis Fidel Castro (1926-) . .110 Premier of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis Anatoly Dobrynin (1919-2010) . .116 Soviet Ambassador to the U.S. during the Cuban Missile Crisis v DM - Cuba 3/4/15 11:19 AM Page vi Defining Moments: The Cuban Missile Crisis Alexander Feklisov (1914-2007) . .120 Russian Spy Who Proposed a Deal to Resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) . .125 President of the United States during the Cuban Missile Crisis Robert F. Kennedy (1925-1968) . .131 U.S. Attorney General and Leader of ExComm Nikita Khrushchev (1891-1971) . .137 Soviet Premier Who Placed Nuclear Missiles in Cuba John McCone (1902-1991) . .144 Director of the CIA during the Cuban Missile Crisis Robert S. McNamara (1916-2009) . .148 U.S. Secretary of Defense during the Cuban Missile Crisis Ted Sorensen (1928-2010) . .153 Special Counsel and Speechwriter for President Kennedy PRIMARY SOURCES The Soviet Union Vows to Defend Cuba . -

Annotated Timeline,” JFK the Last Speech, Mascot Books, 2018, Pp 97-112

Selected Timeline: Kennedy, Frost, and the Amherst College Class of 1964i The focus is on the years 1960-1963 Draft last updated: 13 February 2018 1874 26 Mar Robert Frost was born to William Prescott Frost, Jr., and Isabelle Moodie in San Francisco, CA. 1917 29 May John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK) was born to Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., and Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald in Brookline, MA. 1959 Jan Castro’s revolutionary forces seized power in Cuba, President Batista fled. 26 Mar Press conference prior to Frost’s 85th birthday gala. In response to a question regarding the alleged decline of New England, Frost responded, “The next President of the United States will be from Boston. Does that sound as if New England is decaying? … He’s a Puritan named Kennedy. The only Puritans left these days are the Roman Catholics. There. I guess I wear my politics on my sleeve.” April JFK letter to Frost: “I just want to send you a note to let you know how gratifying it was to be remembered by you on the occasion of your 85th birthday. 1960 1 May Gary Powers’ U2 spy plane was shot down over USSR. Feb Sit-ins by African-Americans at segregated lunch counters began and spread to 65 cities in 12 southern states. 7 May USSR established diplomatic relations with Cuba. 13 Sept An Act of Congress, Public Law P.L. 86-747, 74 Stat. 883, awarded Frost a Congressional Gold Medal, “In recognition of his poetry, which has enriched the culture of the United States and the philosophy of the world.” There apparently was no public award ceremony until JFK took the initiative in March 1962. -

13 Introduction to the Statutes and Regulations

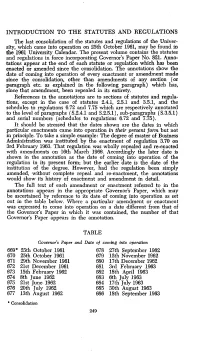

INTRODUCTION TO THE STATUTES AND REGULATIONS The last consolidation of the statutes and regulations of the Univer sity, which came into operation on 25th October 1961, may be found in the 1961 University Calendar. The present volume contains the statutes and regulations in force incorporating Governor's Paper No. 821. Anno tations appear at the end of each statute or regulation which has been enacted or amended since the consolidation. The annotations show the date of coming into operation of every enactment or amendment made since the consolidation, other than amendments of any section (or paragraph etc. as explained in the following paragraph) which has, since that amendment, been repealed in its entirety. References in the annotations are to sections of statutes and regula tions, except in the case of statutes 2.4.1, 2.5.1 and 3.5.1, and the schedules to regulations 6.72 and 7,75 which are respectively annotated to the level of paragraphs (S.2.4.1 and S.2.5.1), sub-paragraphs (S.3.5.1) and serial numbers (schedules to regulations 6.72 and 7.75). It should be stressed that the dates shown are the dates in which particular enactments came into operation in their present form but not in principle. To talce a simple example: The degree of master of Business AoSriinistration was instituted by the enactment of regulation 3.70 on 3rd February 1963. That regulation was wholly repealed and re-enacted with amendments on 16th March 1966. Accordingly the later date is shown in the annotation as the date of coming into operation of the regulation in its present form; but the earlier date is the date of the institution of the degree. -

Konrad Adenauer and the Cuban Missile Crisis: West German Documents

SECTION 5: Non-Communist Europe and Israel Konrad Adenauer and the Cuban Missile Crisis: West German Documents access agency, the exchange of mutual non-aggression declara- d. Note: Much like the other NATO allies of the United tions and the establishment of FRG-GDR technical commissions. States, West Germany was not involved in either the ori- Somehow the proposals leaked to the German press, leading gins or the resolution of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.1 Secretary of State Dean Rusk to protest the serious breach of confi- EBut, of course, nowhere in Europe was the immediate impact of dence. Hurt by the accusation, Adenauer withdrew his longstand- Khrushchev’s nuclear missile gamble felt more acutely than in ing confidante and ambassador to Washington, Wilhelm Grewe. Berlin. Ever since the Soviet premier’s November 1958 ultima- Relations went from cool to icy when the chancellor publicly dis- tum, designed to dislodge Western allied forces from the western tanced himself from Washington’s negotiation package at a press sectors of the former German Reich’s capital, Berlin had been the conference in May. By time the missile crisis erupted in October, focus of heightened East-West tensions. Following the building Adenauer’s trust in the United States had been severely shaken.4 of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 and the October stand-off The missile crisis spurred a momentary warming in the between Soviet and American tanks at the Checkpoint Charlie uneasy Adenauer-Kennedy relationship. Unlike other European crossing, a deceptive lull had settled over the city.2 allies, Adenauer backed Kennedy’s staunch attitude during the cri- Yet the Berlin question (centering around Western rights sis wholeheartedly, a fact that did not go unnoticed in Washington.