96 CHAPTER 5 Shape, Form, and Space CHAPTER 5 Shape, Form, and Space Ou Live in a World Filled with Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swimming in Spacetime: Motion by Cyclic Changes in Body Shape

RESEARCH ARTICLE tation of the two disks can be accomplished without external torques, for example, by fixing Swimming in Spacetime: Motion the distance between the centers by a rigid circu- lar arc and then contracting a tension wire sym- by Cyclic Changes in Body Shape metrically attached to the outer edge of the two caps. Nevertheless, their contributions to the zˆ Jack Wisdom component of the angular momentum are parallel and add to give a nonzero angular momentum. Cyclic changes in the shape of a quasi-rigid body on a curved manifold can lead Other components of the angular momentum are to net translation and/or rotation of the body. The amount of translation zero. The total angular momentum of the system depends on the intrinsic curvature of the manifold. Presuming spacetime is a is zero, so the angular momentum due to twisting curved manifold as portrayed by general relativity, translation in space can be must be balanced by the angular momentum of accomplished simply by cyclic changes in the shape of a body, without any the motion of the system around the sphere. external forces. A net rotation of the system can be ac- complished by taking the internal configura- The motion of a swimmer at low Reynolds of cyclic changes in their shape. Then, presum- tion of the system through a cycle. A cycle number is determined by the geometry of the ing spacetime is a curved manifold as portrayed may be accomplished by increasing by ⌬ sequence of shapes that the swimmer assumes by general relativity, I show that net translations while holding fixed, then increasing by (1). -

Art Concepts for Kids: SHAPE & FORM!

Art Concepts for Kids: SHAPE & FORM! Our online art class explores “shape” and “form” . Shapes are spaces that are created when a line reconnects with itself. Forms are three dimensional and they have length, width and depth. This sweet intro song teaches kids all about shape! Scratch Garden Value Song (all ages) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=coZfbTIzS5I Another great shape jam! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6hFTUk8XqEc Cookie Monster eats his shapes! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gfNalVIrdOw&list=PLWrCWNvzT_lpGOvVQCdt7CXL ggL9-xpZj&index=10&t=0s Now for the activities!! Click on the links in the descriptions below for the step by step details. Ages 2-4 Shape Match https://busytoddler.com/2017/01/giant-shape-match-activity/ Shapes are an easy art concept for the littles. Lots of their environment gives play and art opportunities to learn about shape. This Matching activity involves tracing the outside shape of blocks and having littles match the block to the outline. It can be enhanced by letting your little ones color the shapes emphasizing inside and outside the shape lines. Block Print Shapes https://thepinterestedparent.com/2017/08/paul-klee-inspired-block-printing/ Printing is a great technique for young kids to learn. The motion is like stamping so you teach little ones to press and pull rather than rub or paint. This project requires washable paint and paper and block that are not natural wood (which would stain) you want blocks that are painted or sealed. Kids can look at Paul Klee art for inspiration in stacking their shapes into buildings, or they can chose their own design Ages 4-6 Lois Ehlert Shape Animals http://www.momto2poshlildivas.com/2012/09/exploring-shapes-and-colors-with-color.html This great project allows kids to play with shapes to make animals in the style of the artist Lois Ehlert. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space Martin Kilian Niloy J. Mitra Helmut Pottmann Vienna University of Technology Figure 1: Geodesic interpolation and extrapolation. The blue input poses of the elephant are geodesically interpolated in an as-isometric- as-possible fashion (shown in green), and the resulting path is geodesically continued (shown in purple) to naturally extend the sequence. No semantic information, segmentation, or knowledge of articulated components is used. Abstract space, line geometry interprets straight lines as points on a quadratic surface [Berger 1987], and the various types of sphere geometries We present a novel framework to treat shapes in the setting of Rie- model spheres as points in higher dimensional space [Cecil 1992]. mannian geometry. Shapes – triangular meshes or more generally Other examples concern kinematic spaces and Lie groups which straight line graphs in Euclidean space – are treated as points in are convenient for handling congruent shapes and motion design. a shape space. We introduce useful Riemannian metrics in this These examples show that it is often beneficial and insightful to space to aid the user in design and modeling tasks, especially to endow the set of objects under consideration with additional struc- explore the space of (approximately) isometric deformations of a ture and to work in more abstract spaces. We will show that many given shape. Much of the work relies on an efficient algorithm to geometry processing tasks can be solved by endowing the set of compute geodesics in shape spaces; to this end, we present a multi- closed orientable surfaces – called shapes henceforth – with a Rie- resolution framework to solve the interpolation problem – which mannian structure. -

Shape Synthesis Notes

SHAPE SYNTHESIS OF HIGH-PERFORMANCE MACHINE PARTS AND JOINTS By John M. Starkey Based on notes from Walter L. Starkey Written 1997 Updated Summer 2010 2 SHAPE SYNTHESIS OF HIGH-PERFORMANCE MACHINE PARTS AND JOINTS Much of the activity that takes place during the design process focuses on analysis of existing parts and existing machinery. There is very little attention focused on the synthesis of parts and joints and certainly there is very little information available in the literature addressing the shape synthesis of parts and joints. The purpose of this document is to provide guidelines for the shape synthesis of high-performance machine parts and of joints. Although these rules represent good design practice for all machinery, they especially apply to high performance machines, which require high strength-to-weight ratios, and machines for which manufacturing cost is not an overriding consideration. Examples will be given throughout this document to illustrate this. Two terms which will be used are part and joint. Part refers to individual components manufactured from a single block of raw material or a single molding. The main body of the part transfers loads between two or more joint areas on the part. A joint is a location on a machine at which two or more parts are fastened together. 1.0 General Synthesis Goals Two primary principles which govern the shape synthesis of a part assert that (1) the size and shape should be chosen to induce a uniform stress or load distribution pattern over as much of the body as possible, and (2) the weight or volume of material used should be a minimum, consistent with cost, manufacturing processes, and other constraints. -

Geometry and Art LACMA | | April 5, 2011 Evenings for Educators

Geometry and Art LACMA | Evenings for Educators | April 5, 2011 ALEXANDER CALDER (United States, 1898–1976) Hello Girls, 1964 Painted metal, mobile, overall: 275 x 288 in., Art Museum Council Fund (M.65.10) © Alexander Calder Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris EOMETRY IS EVERYWHERE. WE CAN TRAIN OURSELVES TO FIND THE GEOMETRY in everyday objects and in works of art. Look carefully at the image above and identify the different, lines, shapes, and forms of both GAlexander Calder’s sculpture and the architecture of LACMA’s built environ- ment. What is the proportion of the artwork to the buildings? What types of balance do you see? Following are images of artworks from LACMA’s collection. As you explore these works, look for the lines, seek the shapes, find the patterns, and exercise your problem-solving skills. Use or adapt the discussion questions to your students’ learning styles and abilities. 1 Language of the Visual Arts and Geometry __________________________________________________________________________________________________ LINE, SHAPE, FORM, PATTERN, SYMMETRY, SCALE, AND PROPORTION ARE THE BUILDING blocks of both art and math. Geometry offers the most obvious connection between the two disciplines. Both art and math involve drawing and the use of shapes and forms, as well as an understanding of spatial concepts, two and three dimensions, measurement, estimation, and pattern. Many of these concepts are evident in an artwork’s composition, how the artist uses the elements of art and applies the principles of design. Problem-solving skills such as visualization and spatial reasoning are also important for artists and professionals in math, science, and technology. -

L2/14-274 Title: Proposed Math-Class Assignments for UTR #25

L2/14-274 Title: Proposed Math-Class Assignments for UTR #25 Revision 14 Source: Laurențiu Iancu and Murray Sargent III – Microsoft Corporation Status: Individual contribution Action: For consideration by the Unicode Technical Committee Date: 2014-10-24 1. Introduction Revision 13 of UTR #25 [UTR25], published in April 2012, corresponds to Unicode Version 6.1 [TUS61]. As of October 2014, Revision 14 is in preparation, to update UTR #25 and its data files to the character repertoire of Unicode Version 7.0 [TUS70]. This document compiles a list of characters proposed to be assigned mathematical classes in Revision 14 of UTR #25. In this document, the term math-class is being used to refer to the character classification in UTR #25. While functionally similar to a UCD character property, math-class is applicable only within the scope of UTR #25. Math-class is different from the UCD binary character property Math [UAX44]. The relation between Math and math-class is that the set of characters with the property Math=Yes is a proper subset of the set of characters assigned any math-class value in UTR #25. As of Revision 13, the set relation between Math and math-class is invalidated by the collection of Arabic mathematical alphabetic symbols in the range U+1EE00 – U+1EEFF. This is a known issue [14-052], al- ready discussed by the UTC [138-C12 in 14-026]. Once those symbols are added to the UTR #25 data files, the set relation will be restored. This document proposes only UTR #25 math-class values, and not any UCD Math property values. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

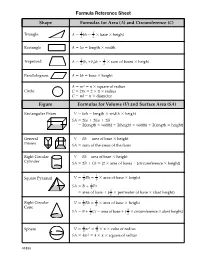

C) Shape Formulas for Volume (V) and Surface Area (SA

Formula Reference Sheet Shape Formulas for Area (A) and Circumference (C) Triangle ϭ 1 ϭ 1 ϫ ϫ A 2 bh 2 base height Rectangle A ϭ lw ϭ length ϫ width Trapezoid ϭ 1 + ϭ 1 ϫ ϫ A 2 (b1 b2)h 2 sum of bases height Parallelogram A ϭ bh ϭ base ϫ height A ϭ πr2 ϭ π ϫ square of radius Circle C ϭ 2πr ϭ 2 ϫ π ϫ radius C ϭ πd ϭ π ϫ diameter Figure Formulas for Volume (V) and Surface Area (SA) Rectangular Prism SV ϭ lwh ϭ length ϫ width ϫ height SA ϭ 2lw ϩ 2hw ϩ 2lh ϭ 2(length ϫ width) ϩ 2(height ϫ width) 2(length ϫ height) General SV ϭ Bh ϭ area of base ϫ height Prisms SA ϭ sum of the areas of the faces Right Circular SV ϭ Bh = area of base ϫ height Cylinder SA ϭ 2B ϩ Ch ϭ (2 ϫ area of base) ϩ (circumference ϫ height) ϭ 1 ϭ 1 ϫ ϫ Square Pyramid SV 3 Bh 3 area of base height ϭ ϩ 1 l SA B 2 P ϭ ϩ 1 ϫ ϫ area of base ( 2 perimeter of base slant height) Right Circular ϭ 1 ϭ 1 ϫ ϫ SV 3 Bh 3 area of base height Cone ϭ ϩ 1 l ϭ ϩ 1 ϫ ϫ SA B 2 C area of base ( 2 circumference slant height) ϭ 4 π 3 ϭ 4 ϫ π ϫ Sphere SV 3 r 3 cube of radius SA ϭ 4πr2 ϭ 4 ϫ π ϫ square of radius 41830 a41830_RefSheet_02MHS 1 8/29/01, 7:39 AM Equations of a Line Coordinate Geometry Formulas Standard Form: Let (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) be two points in the plane. -

Line, Color, Space, Light, and Shape: What Do They Do? What Do They Evoke?

LINE, COLOR, SPACE, LIGHT, AND SHAPE: WHAT DO THEY DO? WHAT DO THEY EVOKE? Good composition is like a suspension bridge; each line adds strength and takes none away… Making lines run into each other is not composition. There must be motive for the connection. Get the art of controlling the observer—that is composition. —Robert Henri, American painter and teacher The elements and principals of art and design, and how they are used, contribute mightily to the ultimate composition of a work of art—and that can mean the difference between a masterpiece and a messterpiece. Just like a reader who studies vocabulary and sentence structure to become fluent and present within a compelling story, an art appreciator who examines line, color, space, light, and shape and their roles in a given work of art will be able to “stand with the artist” and think about how they made the artwork “work.” In this activity, students will practice looking for design elements in works of art, and learn to describe and discuss how these elements are used in artistic compositions. Grade Level Grades 4–12 Common Core Academic Standards • CCSS.ELA-Writing.CCRA.W.3 • CCSS.ELA-Speaking and Listening.CCRA.SL.1 • CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCSL.2 • CCSS.ELA-Speaking and Listening.CCRA.SL.4 National Visual Arts Standards Still Life with a Ham and a Roemer, c. 1631–34 Willem Claesz. Heda, Dutch • Artistic Process: Responding: Understanding Oil on panel and evaluating how the arts convey meaning 23 1/4 x 32 1/2 inches (59 x 82.5 cm) John G. -

Shape, Dimension, and Geometric Relationships Calendar Pacing 3 Times Per Checkpoint

Content Area Mathematics Grade/Course Preschool School Year 2018-19 Framework Number: Name 02: Shape, Dimension, and Geometric Relationships Calendar Pacing 3 times per checkpoint ULTIMATE CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK GOALS Ultimate Performance Task The most important performance we want learners to be able to do with the acquired content knowledge and skills of this framework is: ● to use their understanding of order and position to independently describe location. ● to describe attributes of a new shape in a new orientation or new setting. ● to explain how they independently organized various groups of objects. Transfer Goal(s) Students will be able to independently use their learning to … ● describe shape attributes and positioning in order to describe and understand the environment such as in following directions, organizing and arranging their space through critical thinking and problem solving. Meaning Goals BIG IDEAS / UNDERSTANDINGS ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Students will understand that … Students will keep considering: ● they need to be able to describe the location of objects. ● How do we describe where something is? ● they need to be able to describe the characteristics of shapes ● How are these shapes the same or different? including three-dimensional shapes. ● What ways are objects sorted? IDEAS IMPORTANTES / CONOCIMIENTOS PREGUNTAS ESENCIALES Los estudiantes comprenderán que … Los estudiantes seguirán teniendo en cuenta: ● necesitarán poder describir la ubicación de objetos. ● ¿Cómo describimos la ubicación de las cosas? ● necesitaran describir las características de formas incluyendo ● ¿Cómo son las formas iguales o diferentes? formas tridimensionales. ● ¿En qué maneras se pueden ordenar los objetos? Acquisition Goals In order to reach the ULTIMATE GOALS, students must have acquired the following knowledge, skills, and vocabulary. -

The Case of Basic Geometric Shapes

International Journal of Progressive Education, Volume 15 Number 3, 2019 © 2019 INASED Children’s Geometric Understanding through Digital Activities: The Case of Basic Geometric Shapes Bilal Özçakır i Kırşehir Ahi Evran University Ahmet Sami Konca ii Kırşehir Ahi Evran University Nihat Arıkan iii Kırşehir Ahi Evran University Abstract Early mathematics education bases a foundation of academic success in mathematics for higher grades. Studies show that introducing mathematical contents in preschool level is a strong predictor of success in mathematics for children during their progress in other school levels. Digital technologies can support children’s learning mathematical concepts by means of the exploration and the manipulation of concrete representations. Therefore, digital activities provide opportunities for children to engage with experimental mathematics. In this study, the effects of digital learning tools on learning about geometric shapes in early childhood education were investigated. Hence, this study aimed to investigate children progresses on digital learning activities in terms of recognition and discrimination of basic geometric shapes. Participants of the study were six children from a kindergarten in Kırşehir, Turkey. Six digital learning activities were engaged by children with tablets about four weeks in learning settings. Task-based interview sessions were handled in this study. Results of this study show that these series of activities helped children to achieve higher cognitive levels. They improved their understanding through digital activities. Keywords: Digital Learning Activities, Early Childhood Education, Basic Geometric Shape, Geometry Education DOI: 10.29329/ijpe.2019.193.8 ------------------------------- i Bilal Özçakır, Res. Assist Dr., Kırşehir Ahi Evran University, Mathematics Education. Correspondence: [email protected] ii Ahmet Sami Konca, Res.