Electrodiagnosis of Motor Neuron Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinically Undetected Motor Neuron Disease in Pathologically Proven Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration with Motor Neuron Disease

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Clinically Undetected Motor Neuron Disease in Pathologically Proven Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration With Motor Neuron Disease Keith A. Josephs, MST, MD; Joseph E. Parisi, MD; David S. Knopman, MD; Bradley F. Boeve, MD; Ronald C. Petersen, MD, PhD; Dennis W. Dickson, MD Background: Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with evidence of motor neuron disease. Semiquantitative motor neuron disease (FTLD-MND) is a pathological analysis of motor and extramotor pathological findings entity characterized by motor neuron degeneration and revealed a spectrum of pathological changes underlying frontotemporal lobar degeneration. The ability to detect FTLD-MND. Hippocampal sclerosis, predominantly of the clinical signs of dementia and motor neuron disease the subiculum, was a significantly more frequent occur- in pathologically confirmed FTLD-MND has not been rence in the cases without clinical evidence of motor assessed. neuron disease (PϽ.01). In addition, neuronal loss, gliosis, and corticospinal tract degeneration were less Objectives: To determine if all cases of pathologically severe in the other 3 cases without clinical evidence of confirmed FTLD-MND have clinical evidence of fronto- motor neuron disease. temporal dementia and motor neuron disease, and to de- termine the possible reasons for misdiagnosis. Conclusions: Clinical diagnostic sensitivity for the el- ements of FTLD-MND is modest and may be affected by Method: Review of historical records and semiquantita- the fact that FTLD-MND represents a spectrum of patho- tive analysis of the motor and extramotor pathological find- logical findings, rather than a single homogeneous en- ings of all cases of pathologically confirmed FTLD-MND. tity. Detection of signs of clinical motor neuron disease is also difficult when motor neuron degeneration is mild Results: From a total of 17 cases of pathologically con- and in patients with hippocampal sclerosis. -

Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper Motor Neuron Dominant Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia

brain sciences Review Upper Motor Neuron Disorders: Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper Motor Neuron Dominant Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Timothy Fullam and Jeffrey Statland * Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas, KS 66160, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Following the exclusion of potentially reversible causes, the differential for those patients presenting with a predominant upper motor neuron syndrome includes primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), or upper motor neuron dominant ALS (UMNdALS). Differentiation of these disorders in the early phases of disease remains challenging. While no single clinical or diagnostic tests is specific, there are several developing biomarkers and neuroimaging technologies which may help distinguish PLS from HSP and UMNdALS. Recent consensus diagnostic criteria and use of evolving technologies will allow more precise delineation of PLS from other upper motor neuron disorders and aid in the targeting of potentially disease-modifying therapeutics. Keywords: primary lateral sclerosis; amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; hereditary spastic paraplegia Citation: Fullam, T.; Statland, J. Upper Motor Neuron Disorders: Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper 1. Introduction Motor Neuron Dominant Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) and Wilhelm Erb (1840–1921) are credited with first Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and describing a distinct clinical syndrome of upper motor neuron (UMN) tract degeneration in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia. Brain isolation with symptoms including spasticity, hyperreflexia, and mild weakness [1,2]. Many Sci. 2021, 11, 611. https:// of the earliest described cases included cases of hereditary spastic paraplegia, amyotrophic doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050611 lateral sclerosis, and underrecognized structural, infectious, or inflammatory etiologies for upper motor neuron dysfunction which have since become routinely diagnosed with the Academic Editors: P. -

Neural Control of Movement: Motor Neuron Subtypes, Proprioception and Recurrent Inhibition

List of Papers This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals. I Enjin A, Rabe N, Nakanishi ST, Vallstedt A, Gezelius H, Mem- ic F, Lind M, Hjalt T, Tourtellotte WG, Bruder C, Eichele G, Whelan PJ, Kullander K (2010) Identification of novel spinal cholinergic genetic subtypes disclose Chodl and Pitx2 as mark- ers for fast motor neurons and partition cells. J Comp Neurol 518:2284-2304. II Wootz H, Enjin A, Wallen-Mackenzie Å, Lindholm D, Kul- lander K (2010) Reduced VGLUT2 expression increases motor neuron viability in Sod1G93A mice. Neurobiol Dis 37:58-66 III Enjin A, Leao KE, Mikulovic S, Le Merre P, Tourtellotte WG, Kullander K. 5-ht1d marks gamma motor neurons and regulates development of sensorimotor connections Manuscript IV Enjin A, Leao KE, Eriksson A, Larhammar M, Gezelius H, Lamotte d’Incamps B, Nagaraja C, Kullander K. Development of spinal motor circuits in the absence of VIAAT-mediated Renshaw cell signaling Manuscript Reprints were made with permission from the respective publishers. Cover illustration Carousel by Sasha Svensson Contents Introduction.....................................................................................................9 Background...................................................................................................11 Neural control of movement.....................................................................11 The motor neuron.....................................................................................12 Organization -

Inside Your Brain You and Your Brain

Inside your brain You and your brain Many simple and complex psychological functions are mediated by multiple brain regions and, at the same time, a single brain area may control many psychological functions. CC BY Illustration by Bret Syfert 1. Cortex: The thin, folded structure on the outside surface of the brain. 2. Cerebral hemispheres: The two halves of the brain, each of which controls and receives information from the opposite side of the body. 3. Pituitary gland: The ‘master gland’ of the body, which releases hormones that control growth, blood pressure, the stress response and the function of the sex organs. 4. Substantia nigra: The ‘black substance’ contains cells that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine and the pigment melatonin, giving it a black appearance. 5. Hypothalamus: The interface between the brain and pituitary gland. It controls the production and release of hormones. 6. Spinal cord: A large bundle of millions of nerve fibres and neuronal cells, which carries information back and forth between the brain and the body. 7. Medulla oblongata: Controls vital involuntary functions such as breathing and heart rate. 8. Cerebellum: The ‘little brain’ that controls balance and coordinates movements. It’s normally required for learning motor skills, such as riding a bike, and is involved in thought processes. 9. Cranial nerve nuclei: Clusters of neurons in the brain stem. Their axons form the cranial nerves. Your brain underpins who you are. It stores your knowledge and memories, gives you the capacity for thought and emotion, and enables you to control your body. The brain is just one part of the nervous system. -

Management of Postpolio Syndrome

Review Management of postpolio syndrome Henrik Gonzalez, Tomas Olsson, Kristian Borg Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 634–42 Postpolio syndrome is characterised by the exacerbation of existing or new health problems, most often muscle weakness See Refl ection and Reaction and fatigability, general fatigue, and pain, after a period of stability subsequent to acute polio infection. Diagnosis is page 561 based on the presence of a lower motor neuron disorder that is supported by neurophysiological fi ndings, with exclusion Division of Rehabilitation of other disorders as causes of the new symptoms. The muscle-related eff ects of postpolio syndrome are possibly Medicine, Department of associated with an ongoing process of denervation and reinnervation, reaching a point at which denervation is no Clinical Sciences, Danderyd Hospital (H Gonzalez MD, longer compensated for by reinnervation. The cause of this denervation is unknown, but an infl ammatory process is K Borg MD) and Department of possible. Rehabilitation in patients with postpolio syndrome should take a multiprofessional and multidisciplinary Clinical Neurosciences, Centre approach, with an emphasis on physiotherapy, including enhanced or individually modifi ed physical activity, and muscle for Molecular Medicine training. Patients with postpolio syndrome should be advised to avoid both inactivity and overuse of weak muscles. (T Olsson MD), Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden Evaluation of the need for orthoses and assistive devices is often required. Correspondence to: Henrik Gonzalez, Division of Introduction summary of the pathophysiology and clinical Rehabilitation Medicine, 12–20 million people worldwide have sequelae of characteristics of postpolio syndrome, outline diagnostic Department of Clinical Sciences, poliomyelitis, according to Post-Polio Health and treatment options, and suggest future research Karolinska Institute, Danderyd Hospital, S-182 88 Stockholm, International. -

ALS and Other Motor Neuron Diseases Can Represent Diagnostic Challenges

Review Article Address correspondence to Dr Ezgi Tiryaki, Hennepin ALS and Other Motor County Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 701 Park Avenue P5-200, Neuron Diseases Minneapolis, MN 55415, [email protected]. Ezgi Tiryaki, MD; Holli A. Horak, MD, FAAN Relationship Disclosure: Dr Tiryaki’s institution receives support from The ALS Association. Dr Horak’s ABSTRACT institution receives a grant from the Centers for Disease Purpose of Review: This review describes the most common motor neuron disease, Control and Prevention. ALS. It discusses the diagnosis and evaluation of ALS and the current understanding of its Unlabeled Use of pathophysiology, including new genetic underpinnings of the disease. This article also Products/Investigational covers other motor neuron diseases, reviews how to distinguish them from ALS, and Use Disclosure: Drs Tiryaki and Horak discuss discusses their pathophysiology. the unlabeled use of various Recent Findings: In this article, the spectrum of cognitive involvement in ALS, new concepts drugs for the symptomatic about protein synthesis pathology in the etiology of ALS, and new genetic associations will be management of ALS. * 2014, American Academy covered. This concept has changed over the past 3 to 4 years with the discovery of new of Neurology. genes and genetic processes that may trigger the disease. As of 2014, two-thirds of familial ALS and 10% of sporadic ALS can be explained by genetics. TAR DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43), for instance, has been shown to cause frontotemporal dementia as well as some cases of familial ALS, and is associated with frontotemporal dysfunction in ALS. Summary: The anterior horn cells control all voluntary movement: motor activity, res- piratory, speech, and swallowing functions are dependent upon signals from the anterior horn cells. -

Motor Neuron Disease and the Elderly

Neurology 61 Motor neuron disease and the elderly Motor neuron disease is a devastating condition characterised by degeneration of motor nerves. Many of the presenting symptoms, such as fatigue, muscle weakness and difficulty in swallowing have a broad differential diagnoses in the elderly population. Dr Sheba Azam and Professor PN Leigh explain how ensuring quality of life for patients requires preventing unnecessary delay in diagnosis and early referral to an appropriate multidisciplinary team. myotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) also cognitive changes. Thus, misdiagnosis as well as known as motor neuron disease (MND) under-investigation has been suggested as possible (the terms are used interchangeably), was causes of an apparent decrease in the incidence of A 4 fi rst described in 1869 by the French neurologist MND in later life . Jean-Martin Charcot1. It is a progressive, fatal neurological disease characterised by degeneration of motor nerve cells in the motor cortex, Prognostic factors corticospinal tract and the spinal cord anterior horn Although the average survival in MND is around cells. The degeneration of motor nerve cells results 36 months, some patients live for 10 years or more. in progressive muscle wasting leading to signifi cant Certain phenotypic variants appear to determine disability and ultimately death. Death usually survival rates. Using information held in a tertiary results from respiratory failure due to weakness of referral MND database, a group of researchers the respiratory muscles. analysed data on onset of disease, site of onset and duration of survival5. The authors concluded that typical MND with bulbar onset, onset later in life Incidence and prevalence or in the defi nite category of El Escorial (where The worldwide incidence of MND is approximately the World Federation of Neurologist meet to a professor of clinical two per 100,000 and the prevalence is four to seven decide diagnostic criteria) at presentation, per 100,000. -

Reaction to Injury & Regeneration

Reaction to Injury & Regeneration Steven McLoon Department of Neuroscience University of Minnesota 1 The adult mammalian central nervous system has the lowest regenerative capacity of all organ systems. 2 3 Reaction to Axotomy Function distal to the axon cut is lost. (immediate) 4 Reaction to Axotomy • Spinal cord injury results in an immediate loss of sensation and muscle paralysis below the level of the injury. Spinal cord injury can be partial or complete, and the sensory/motor loss depends on which axons are injured. • Peripheral nerve injury results in an immediate loss of sensation and muscle paralysis in the areas served by the injured nerve distal to the site of injury. 5 Reaction to Axotomy K+ leaks out of the cell and Na+/Ca++ leak into the cell. (seconds) Proximal and distal segments of the axon reseal slightly away from the cut ends. (~2 hrs) Subsequent anterograde & retrograde effects … 6 Anterograde Effects (Wallerian Degeneration) Axon swells. (within 12 hrs) Axolema and mitochondria begin to fragment. (within 3 days) Myelin not associated with a viable axon begins to fragment. (within 1 wk) Astrocytes or Schwann cells proliferate (within 1 wk), which can continue for over a month. Results in >10x the original number of cells. Microglia (or macrophages in the PNS) invade the area. Glia and microglia phagocytize debris. (1 month in PNS; >3 months in CNS) 7 Anterograde Effects (Wallerian Degeneration) Degradation of the axon involves self proteolysis: In the ‘Wallerian degeneration slow’ (Wlds) mouse mutation, the distal portion of severed axons are slow to degenerate; the dominant mutation involves a ubiquitin regulatory enzyme. -

Lancl1 Promotes Motor Neuron Survival and Extends the Lifespan of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Mice

Cell Death & Differentiation (2020) 27:1369–1382 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-019-0422-6 ARTICLE LanCL1 promotes motor neuron survival and extends the lifespan of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Honglin Tan ● Mina Chen ● Dejiang Pang ● Xiaoqiang Xia ● Chongyangzi Du ● Wanchun Yang ● Yiyuan Cui ● 1,2 1 1,3 4 4 3 1,5 Chao Huang ● Wanxiang Jiang ● Dandan Bi ● Chunyu Li ● Huifang Shang ● Paul F. Worley ● Bo Xiao Received: 19 November 2018 / Revised: 3 September 2019 / Accepted: 6 September 2019 / Published online: 30 September 2019 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is published with open access Abstract Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive loss of motor neurons. Improving neuronal survival in ALS remains a significant challenge. Previously, we identified Lanthionine synthetase C-like protein 1 (LanCL1) as a neuronal antioxidant defense gene, the genetic deletion of which causes apoptotic neurodegeneration in the brain. Here, we report in vivo data using the transgenic SOD1G93A mouse model of ALS indicating that CNS-specific expression of LanCL1 transgene extends lifespan, delays disease onset, decelerates symptomatic progression, and improves motor performance of SOD1G93A mice. Conversely, CNS-specific deletion of fl 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: LanCL1 leads to neurodegenerative phenotypes, including motor neuron loss, neuroin ammation, and oxidative damage. Analysis reveals that LanCL1 is a positive regulator of AKT activity, and LanCL1 overexpression restores the impaired AKT activity in ALS model mice. These findings indicate that LanCL1 regulates neuronal survival through an alternative mechanism, and suggest a new therapeutic target in ALS. -

Microglia and Macrophages in the Pathological Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

cells Review Microglia and Macrophages in the Pathological Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems Naoki Abe 1, Tasuku Nishihara 1,*, Toshihiro Yorozuya 1 and Junya Tanaka 2 1 Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Ehime University Graduate School of Medicine, Toon, Ehime 791-0295, Japan; [email protected] (N.A.); [email protected] (T.Y.) 2 Department of Molecular and cellular Physiology, Ehime University Graduate School of Medicine, Toon, Ehime 791-0295, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-89-960-5383; Fax: +81-89-960-5386 Received: 4 August 2020; Accepted: 17 September 2020; Published: 21 September 2020 Abstract: Microglia, the immunocompetent cells in the central nervous system (CNS), have long been studied as pathologically deteriorating players in various CNS diseases. However, microglia exert ameliorating neuroprotective effects, which prompted us to reconsider their roles in CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS) pathophysiology. Moreover, recent findings showed that microglia play critical roles even in the healthy CNS. The microglial functions that normally contribute to the maintenance of homeostasis in the CNS are modified by other cells, such as astrocytes and infiltrated myeloid cells; thus, the microglial actions on neurons are extremely complex. For a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of various diseases, including those of the PNS, it is important to understand microglial functioning. In this review, we discuss both the favorable and unfavorable roles of microglia in neuronal survival in various CNS and PNS disorders. We also discuss the roles of blood-borne macrophages in the pathogenesis of CNS and PNS injuries because they cooperatively modify the pathological processes of resident microglia. -

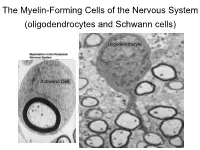

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Cortex Brainstem Spinal Cord Thalamus Cerebellum Basal Ganglia

Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology HST.131: Introduction to Neuroscience Course Director: Dr. David Corey Motor Systems I 1 Emad Eskandar, MD Motor Systems I - Muscles & Spinal Cord Introduction Normal motor function requires the coordination of multiple inter-elated areas of the CNS. Understanding the contributions of these areas to generating movements and the disturbances that arise from their pathology are important challenges for the clinician and the scientist. Despite the importance of diseases that cause disorders of movement, the precise function of many of these areas is not completely clear. The main constituents of the motor system are the cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord. Cortex Basal Ganglia Cerebellum Thalamus Brainstem Spinal Cord In very broad terms, cortical motor areas initiate voluntary movements. The cortex projects to the spinal cord directly, through the corticospinal tract - also known as the pyramidal tract, or indirectly through relay areas in the brain stem. The cortical output is modified by two parallel but separate re entrant side loops. One loop involves the basal ganglia while the other loop involves the cerebellum. The final outputs for the entire system are the alpha motor neurons of the spinal cord, also called the Lower Motor Neurons. Cortex: Planning and initiation of voluntary movements and integration of inputs from other brain areas. Basal Ganglia: Enforcement of desired movements and suppression of undesired movements. Cerebellum: Timing and precision of fine movements, adjusting ongoing movements, motor learning of skilled tasks Brain Stem: Control of balance and posture, coordination of head, neck and eye movements, motor outflow of cranial nerves Spinal Cord: Spontaneous reflexes, rhythmic movements, motor outflow to body.