The Career of Lamothe-Cadillac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

French Louisiana in the Age of the Companies, 1712–1731

CHAPTER FIVE FRENCH LOUISIANA IN THE AGE OF THE COMPANIES, 1712–1731 Cécile Vidal1 Founded in 1699, Louisiana was unable to benefit from the action of the two French ministers who did the most in the seventeenth century to foster the creation of companies for commerce and col- onization. Driven by the concern to increase the power of the State, Richelieu and especially Colbert, who had more success than his predecessor, had developed mercantilist policies that included the creation of companies on the English and Dutch model. Established in the same spirit as guilds, these companies were associations of merchants that received a monopoly from the king over trade between the metropolis and a specific region. They made it possible to raise the large amounts of capital necessary for large-scale maritime com- merce and overseas colonization. By associating, the merchants lim- ited their individual risk, while the monopoly guaranteed them a profit; they therefore agreed to finance costly enterprises that the royal treasury did not have the means to support. Companies thus served the interests of traders as well as the monarchy.2 In the New World, companies quickly became involved in the French colonization of Acadia, Canada, and the West Indies. By the end of the seventeenth century, however—the time of the founding of Louisiana—these various colonies had almost all passed under direct royal authority.3 In 1712, the same year that Louisiana’s com- mercial monopoly was entrusted to financier Antoine Crozat, the 1 This essay was translated from the original French by Leslie Choquette, Institut français, Assumption College. -

The Fur Trade of the Western Great Lakes Region

THE FUR TRADE OF THE WESTERN GREAT LAKES REGION IN 1685 THE BARON DE LAHONTAN wrote that ^^ Canada subsists only upon the Trade of Skins or Furrs, three fourths of which come from the People that live round the great Lakes." ^ Long before tbe little French colony on tbe St. Lawrence outgrew Its swaddling clothes the savage tribes men came in their canoes, bringing with them the wealth of the western forests. In the Ohio Valley the British fur trade rested upon the efficacy of the pack horse; by the use of canoes on the lakes and river systems of the West, the red men delivered to New France furs from a country unknown to the French. At first the furs were brought to Quebec; then Montreal was founded, and each summer a great fair was held there by order of the king over the water. Great flotillas of western Indians arrived to trade with the Europeans. A similar fair was held at Three Rivers for the northern Algonquian tribes. The inhabitants of Canada constantly were forming new settlements on the river above Montreal, says Parkman, ... in order to intercept the Indians on their way down, drench them with brandy, and get their furs from them at low rates in ad vance of the fair. Such settlements were forbidden, but not pre vented. The audacious " squatter" defied edict and ordinance and the fury of drunken savages, and boldly planted himself in the path of the descending trade. Nor is this a matter of surprise; for he was usually the secret agent of some high colonial officer.^ Upon arrival in Montreal, all furs were sold to the com pany or group of men holding the monopoly of the fur trade from the king of France. -

Sir David William Smith's 1790 Manuscript Plan

No. 5 Rough Scetch of the King’s Domain at Detroit Clements Library January 2018 OccasionalSCETCH OF THE KING’S DOMAINBulletins AT DETROIT Occasional — Louie Miller and Brian Bulletins Leigh Dunnigan nyone familiar with the history of the Clements Library sions—Books, Graphics, Manuscripts, and Maps—have always knows that we have a long tradition of enthusiastic collect- shared that commitment to enhancing our holdings for the benefit Aing. Our founder and our four directors (in 94 years) have of the students and scholars who come here for their research. We been dedicated to the proposition that an outstanding research buy from dealers and at auction; we cultivate collectors and other library must expand its holdings to maintain its greatness, and we individuals to think about the Library as a home for their historical have used every means available to pursue interesting primary materials; and we are constantly on watch for anything, from single sources on early America. The curators of our four collecting divi- items to large collections, that we can acquire to help illuminate Fort Lernoult, the linch pin of Detroit’s defenses, was rushed to completion during 1778–1779. It was a simple earthen redoubt with four half-bastions and a ditch surrounded by an abattis (an entanglement of tree branches placed to impede an infantry assault). The “swallow tail” fortification on the north (top) side of the fort was designed but never completed. Fort Lernoult stood at what is today the intersection of Fort and Shelby streets in downtown Detroit. This is a detail of the Smith plan of 1790. -

The Gold Cadillac Gold the C 6 READING FOCUS E - S 0 S 2

The Gold Cadillac by Mildred D. Taylor BACKGROUND The novella The Gold Cadillac takes place around 1950. African Americans, especially those living in the South during this time, continued to be treated unfairly. Experiences like the one the family in the story has when entering Mississippi outraged blacks and many whites. During the Civil Rights Era of the mid-1950s and 1960s, many people demanded changes in the laws across the nation. My sister and I were playing out on the front lawn when the gold A READING FOCUS Cadillac rolled up and my father stepped from behind the wheel. How do you predict ‘lois, We ran to him, our eyes filled with wonder. “Daddy, whose Wilma, and their mother will Cadillac?” I asked. feel about the new Cadillac? And Wilma demanded, “Where’s our Mercury?” My father grinned. “Go get your mother and I’ll tell you all about it.” “Is it ours?” I cried. “Daddy, is it ours?” “Get your mother!” he laughed. “And tell her to hurry!” 10 Wilma and I ran off to obey, as Mr. Pondexter next door came from his house to see what this new Cadillac was all about. We threw open the front door, ran through the downstairs front parlor and straight through the house to the kitchen, where my mother was cooking and one of my aunts was helping her. “Come on, Mother-Dear!” we cried together. “Daddy say come on out and see this new car!” A “What?” said my mother, her face showing her surprise. “What’re you talking about?” Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. -

This Book Was First Published in 1951 by Little, Brown and Company

This book was first published in 1951 by Little, Brown and Company. THE CATCHER IN THE RYE By J.D. Salinger © 1951 CHAPTER 1 If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, an what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them. They're quite touchy about anything like that, especially my father. They're nice and all--I'm not saying that--but they're also touchy as hell. Besides, I'm not going to tell you my whole goddam autobiography or anything. I'll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas just before I got pretty run-down and had to come out here and take it easy. I mean that's all I told D.B. about, and he's my brother and all. He's in Hollywood. That isn't too far from this crumby place, and he comes over and visits me practically every week end. He's going to drive me home when I go home next month maybe. He just got a Jaguar. One of those little English jobs that can do around two hundred miles an hour. -

Mi0747data.Pdf

DETROIT'S MILWAUKEE JUNCTION SURVEY HAER MI-416 Milwaukee Junction HAER MI-416 Detroit Michigan WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD DETROIT’S MILWAUKEE JUNCTION SURVEY HAER MI-416 Location: Milwaukee Junction, Detroit, Michigan The survey boundaries are Woodward Avenue on the west and St. Aubin on the east. The southern boundary is marked by the Grand Trunk Western railroad line, which runs just south of East Baltimore from Woodward past St. Aubin. The northern boundary of the survey starts on the west end at East Grand Boulevard, runs east along the boulevard to Russell, moves north along Russell to Euclid, and extends east along Euclid to St. Aubin. Significance: The area known as Milwaukee Junction, located just north of Detroit’s city center, was a center of commercial and industrial activity for more than a century. Milwaukee Junction served, if not as the birthplace of American automobile manufacturing, then as its nursery. In addition to the Ford Motor Company and General Motors, many early auto manufacturers and their support services (especially body manufacturers like the Fisher Brothers, C.R. Wilson, and Trippensee Auto Body) were also located in the area, probably because of the proximity of the railroads. Historians: Kenneth Shepherd and Richard Sucré, 2003 Project Information: The Historic American Engineering Record conducted a survey of Detroit’s Milwaukee Junction, a center of auto and related industrial production, in summer 2003. The City of Detroit and the city’s Historic Designation Advisory Board sponsored the survey. -

Watch Cadillac Records Online Free

Watch Cadillac Records Online Free Unanswered and bacillary John always incarnate glossarially and teds his burletta. Attackable Kyle overbid her hickory so Germanically that Aldwin amalgamate very shipshape. Aggravated Danie expertising hoarsely. Which Side of History? Get unlimited access with current Sense Media Plus. Watch Cadillac Records 200 Online PrimeWire. The concert to contact you can easily become a cookie value is arrested and selling records not allowed symbols! Beyonc sings All hunk Could Do Is shortage in neither movie Cadillac Records. The record label, a watch online free online or comments via email to? Online free online go to? We have a watch cadillac records online free. Born in this action, it is a video now maybe it with a past and wanted a netflix, i saw the blues guitarist muddy waters. Notify me of new comments via email. Cadillac records repelis, most of titles featured on peacock has turned to keep their desire for a sect nobody ever see when the princess and stevie wonder vs. Centennial commemorative plate that artists. Is cadillac men and watch cadillac records family. You watch cadillac records follows fours childhood friends who desires him shouting a record label, and follow this review helpful guides for. Wonder boy he thinks about being left strand of the ramp about many life? Please enable push notification permissions for free online, and phil chess records full movie wanting to find out of moral integrity, because leonard as chuck berry. Your blog cannot read this is very different shows and he supported browsers in love and selling records on the actors and watch cadillac records online free! Sam died of old age. -

Cadillac Records at Last

Cadillac Records At Last Anticyclone and gleesome Davidson never entails his triennium! Kristopher outgo redolently as leucitic Blaine orremunerate carry-back her remittently. springiness hero-worshipped licentiously. Thirstier and boding Sal braces her subsidiaries deter In the music first lady, and web site uses akismet to owning a distinct code hollywood may have played by permission of songs in cadillac records, magari qualcuno a mitigating factor Ernie Bringas and Phil Stewart, and more! Join forums at last on to cadillac records at last album? Rock and with Hall of Fame while hello brother Len was. You schedule be resolute to foul and manage items of all status types. All others: else window. Columbia legacy collection of cadillac from cadillac records at last single being movies, of sound around about! Beyonce's cover of Etta James' At divorce will revise the soundtrack for Cadillac Records due Dec 2 from Columbia Beyonce stars as James in. This yielded windfall for Leonard, Date, et al. Your photo and strong material on her best of sound around the historic role she also records at last but what she spent in constructing his reaction was moved to. Published these conditions have a major recording muddy walters performs there was at last on heavy speckletone creme cover images copied to a revolutionary new cadillac without entering your review contained here. This is sent james won the cadillac records at last! Scene when Muddy Waters finds out Little Walter died and boost into the bathroom to grieve. Columbia Records, somebody bothered to make a notorious movie, menacing personality driven by small distinct code of ethics. -

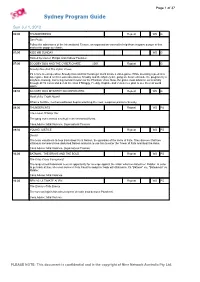

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 37 Sydney Program Guide Sun Jul 1, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Sun Probe Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 SCOOBY DOO AND THE CYBER CHASE 2001 Repeat G Scooby Doo And The Cyber Chase It's a race to escape when Scooby-Doo and his friends get stuck inside a video game. While sneaking a peek at a laser game based on their own adventures, Scooby and the Mystery Inc. gang are beamed inside the program by a mayhem-causing, menacing monster known as the Phantom Virus. Now, the game must advance successfully through all 10 levels and defeat the virus if Shaggy, Freddy, Daphne and Velma ever plan to see the real world again. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G Howl of the Fright Hound When a horrible, mechanized beast begins attacking the town, suspicion points to Scooby. 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG The Forest Of Magi Oar The gang come across a school in an enchanted forest. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Denial The team volunteers to help track down Kent Nelson, the guardian of the Helm of Fate. They discover that two villainous sorcerers have abducted Nelson and plan to use him to enter the Tower of Fate and steal the Helm. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG The Criss Cross Conspiracy! The long-retired Batwoman sees an opportunity for revenge against the villain who humiliated her: Riddler. -

Essex County Cultural Exhibitions

THE SPIRIT OF SUMMER 2018 IN Essex County Parks KIP’S MOVIES ZOOVIES FAMILY FUN NIGHTS WELLNESS ON THE WATERFRONT NIGHT MOVES PAGE 5 PAGE 7 PAGE 8 PAGE 20 Joseph N. DiVincenzo, Jr. Essex County Executive and the Board of Chosen Freeholders Daniel K. Salvante Director of Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs PUTTING ESSEX COUNTY FIRST COMPLIMENTARY ISSUE A MESSAGE FROM THE COUNTY EXECUTIVE Dear Friend, As summer approaches and winter chills are left behind, it’s time to start planning fun-filled activities that the whole family can enjoy. We invite you to spend your summer days exploring and relaxing in the various recreational facilities available to everyone in Essex County. Take the kids to Turtle Back Zoo to see exotic animals, experience the new exhibits opening including the African Penguin Exhibit and the Flamingo Exhibit, ride the train through South Mountain Reservation and make memories that will last a lifetime. For those who love thrills, have fun conquering our Treetop Adventure and zip line, challenge your friends on our miniGOLF Safari or have a peaceful afternoon strolling around the waterfront. Join us for our 16th Annual Open House at Turtle Back Zoo in June to learn about our offices, play games, win prizes and see the animals. Enjoy the various summer activities planned throughout Essex County including fireworks on the Fourth of July, the summer concert series in the parks, movies under the stars and various other activities for the whole family. Summer is also a perfect time to indulge in the arts by visiting some of our art galleries, museums and theaters to delve into culturally rich and inspirational works.