Crisis in Mali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Territorial Autonomy and Self-Determination Conflicts: Opportunity and Willingness Cases from Bolivia, Niger, and Thailand

ICIP WORKING PAPERS: 2010/01 GRAN VIA DE LES CORTS CATALANES 658, BAIX 08010 BARCELONA (SPAIN) Territorial Autonomy T. +34 93 554 42 70 | F. +34 93 554 42 80 [email protected] | WWW.ICIP.CAT and Self-Determination Conflicts: Opportunity and Willingness Cases from Bolivia, Niger, and Thailand Roger Suso Territorial Autonomy and Self-Determination Conflicts: Opportunity and Willingness Cases from Bolivia, Niger, and Thailand Roger Suso Institut Català Internacional per la Pau Barcelona, April 2010 Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes, 658, baix. 08010 Barcelona (Spain) T. +34 93 554 42 70 | F. +34 93 554 42 80 [email protected] | http:// www.icip.cat Editors Javier Alcalde and Rafael Grasa Editorial Board Pablo Aguiar, Alfons Barceló, Catherine Charrett, Gema Collantes, Caterina Garcia, Abel Escribà, Vicenç Fisas, Tica Font, Antoni Pigrau, Xavier Pons, Alejandro Pozo, Mònica Sabata, Jaume Saura, Antoni Segura and Josep Maria Terricabras Graphic Design Fundació Tam-Tam ISSN 2013-5793 (online edition) 2013-5785 (paper edition) DL B-38.039-2009 © 2009 Institut Català Internacional per la Pau · All rights reserved T H E A U T HOR Roger Suso holds a B.A. in Political Science (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, UAB) and a M.A. in Peace and Conflict Studies (Uppsa- la University). He gained work and research experience in various or- ganizations like the UNDP-Lebanon in Beirut, the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) in Berlin, the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights to the Maghreb Elcàlam in Barcelona, and as an assist- ant lecturer at the UAB. An earlier version of this Working Paper was previously submitted in May 20, 2009 as a Master’s Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies in the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, Swe- den, under the supervisor of Thomas Ohlson. -

Report of the Secretary-General on the Situation in Mali

United Nations S/2016/1137 Security Council Distr.: General 30 December 2016 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 2295 (2016), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) until 30 June 2017 and requested me to report on a quarterly basis on its implementation, focusing on progress in the implementation of the Agreement on Peace and Reconciliation in Mali and the efforts of MINUSMA to support it. II. Major political developments A. Implementation of the peace agreement 2. On 23 September, on the margins of the general debate of the seventy-first session of the General Assembly, I chaired, together with the President of Mali, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, a ministerial meeting aimed at mitigating the tensions that had arisen among the parties to the peace agreement between July and September, giving fresh impetus to the peace process and soliciting enhanced international support. Following the opening session, the event was co-chaired by the Minister for Foreign Affairs, International Cooperation and African Integration of Mali, Abdoulaye Diop, and the Minister of State, Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Algeria, Ramtane Lamamra, together with the Under - Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations. In the Co-Chairs’ summary of the meeting, the parties were urged to fully and sincerely maintain their commitments under the agreement and encouraged to take specific steps to swiftly implement the agreement. Those efforts notwithstanding, progress in the implementation of the agreement remained slow. Amid renewed fighting between the Coordination des mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA) and the Platform coalition of armed groups, key provisions of the agreement, including the establishment of interim authorities and the launch of mixed patrols, were not put in place. -

1St Reported Case of Ebola in Mali: Strengthened Measures to Respond

Humanitarian Bulletin Mali September-October 2014 In this issue 1st case of Ebola virus disease P.1 Nutritional situation in Mali P.2 Food security survey P.3 HIGHLIGHTS Back to school 2014 - 2015 P.4 Information management trainings P.6 First confirmed case of SRP funding P.8 Ebola virus disease in Mali Clusters performance indicators P.8 Average prevalence of global acute malnutrition OCHA/D.Dembele reaches 13.3 percent National Food security 1st reported case of Ebola in Mali: survey : 24 per cent of households affected by strengthened measures to respond to the food insecurity epidemic KEY FIGURES On 23 October, the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene confirmed the first Ebola case in Mali; a two-year old girl who had travelled with her grandmother from Guinea # IDPs 99, 816 (Kissidougou) to Kayes city (Western Mali), transiting through Bamako. She had been (Commission on hospitalized in Kayes where she died on 24 October. Population Movements, 30 Sep.) In response to this Ebola outbreak, the Government, with the support of WHO and # Refugees in 14, 541 partners (NGOs and other UN agencies), have strengthened prevention measures while Mali (UNHCR 31 the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene and its partners immediately put under August) observation around forty people who had direct contact with the girl in Bamako and # Malian 143, 253 refugees ( UNHCR Kayes, while the tracking of other contacts continued. 30 Sep) Severely food 1,900,000 Experts from WHO regional office and headquarters, supported by the National Public insecure people Health Institute of Quebec (INSRPQ), USAID and CDC1, who were on a Ebola (Source : March 2014 Harmonized preparedness mission in Mali at the time, are supporting the response and the Framework) implementation of the National Ebola Emergency Plan. -

The Making of Terrorists: Anthropology and the Alternative Truth of America’S ‘War on Terror’ in the Sahara

The making of terrorists: Anthropology and the alternative truth of America’s ‘War on Terror’ in the Sahara Jeremy Keenan Abstract: This article, based on almost eight years of continuous anthropological research amongst the Tuareg people of the Sahara and Sahel, suggests that the launch by the US and its main regional ally, Algeria, in 2002–2003 of a ‘new’,‘sec- ond’,or ‘Saharan’ Front in the ‘War on Terror’ was largely a fabrication on the part of the US and Algerian military intelligence services. The ‘official truth’,embodied in an estimated 3,000 articles and reports of one sort or another, is largely disin- formation. The article summarizes how and why this deception was effected and examines briefly its implications for both the region and its people as well as the future of US international relations and especially its global pursuance of an in- creasingly suspect ‘War on Terror’. Keywords: Algeria, disinformation, Sahara, Tuareg, ‘War on Terror’ I first undertook anthropological fieldwork Sahara following its effective closure to the out- amongst the Tuareg of the Central Sahara, side world during the eight-year period of civil mostly amongst the Kel Ahaggar of southern conflict that followed the Algerian army’s annul- Algeria, during the period 1964–1971.1 It was ment of the 1991–1992 elections that would have a period of tumultuous change, following the brought to power the world’s first ever demo- recent independence of Algeria (1962), during cratically elected Islamist government. I was thus which a number of pressures, notably successive able to witness an entire society, in one of the drought years and a number of ideologically world’s most isolated and remote regions, re- driven government policies, led to some 50 per- enter and begin to catch up, as it were, with the cent of the Kel Ahaggar being more or less sed- modern world. -

Mali 2017 Human Rights Report

MALI 2017 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Mali is a constitutional democracy. In 2013 President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita won the presidential election, deemed free and fair by international observers. The inauguration of President Keita and the subsequent establishment of a new National Assembly through free and fair elections ended a 16-month transitional period following the 2012 military coup that ousted the previous democratically elected president, Amadou Toumani Toure. The restoration of a democratic government and the arrest of coup leader Amadou Sanogo restored some civilian control over the military. Civilian authorities did not always maintain effective control over the security forces. Despite the signing of the Algiers Accord for Peace and Reconciliation in June 2015 between the government, the Platform of northern militias, and the Coordination of Movements of Azawad (CMA), violent conflict between CMA and Platform forces continued throughout the northern region. The terrorist coalition Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wa Muslimin (Support to Islam and Muslims, JNIM)--comprised of Ansar al-Dine, al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the Macina Liberation Front (MLF)--was not a party to the peace process. JNIM carried out attacks on the military, armed groups, UN peacekeepers and convoys, international forces, humanitarian actors, and civilian targets throughout northern Mali and the Mopti and Segou regions of central Mali. The most significant human rights issues included arbitrary deprivation of life; disappearances; torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest; excessively long pretrial detention; denial of fair public trial; female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), which was common and not prohibited by law; the recruitment and use of child soldiers by armed groups, some of which were affiliated with the government; and trafficking in persons. -

O-Dark-Thirty a Literary Journal

O-Dark-Thirty A Literary Journal Spring 2014 Volume 2 Number 3 On the cover: was the second morning of a three It day clearing operation on an island “in the Tigris River not far from Bayji, Iraq, in November 2005. I was embedded with A CO. 1/187 Infantry, the 'Rakkasans.' I saw Willie, Doc and Tim in that field to my right, peeled off one frame of black-and-white film and ended up with this.” Bill Putnam enlisted in the Army in 1995 and served as a Patriot Missile Crewman and a public affairs specialist, deploying to Saudi Arabia, Kosovo, and Iraq. He left the Army in 2005 and began his freelance career by returning to Iraq for another nine months. His work has been pub- lished in newspapers and magazines around the world, appeared in an Oscar-nominated documentary; there have been three solo exhibitions of his war photography. Table of Contents Non-fiction Things I learned during WarMatt Young 11 Sayyed's Poem Jim Enderle 23 Fiction The Blood VialBryon Rieger 31 Shibuya Station Tom Miller Juvik 41 Amusement for the Lazy Alexander Fenno 49 Poetry Ishmael Michael D. Fay 55 Missing Piece Vallanelle John Rodriguez 59 Incoming Carl Palmer 61 Troops In Contact José Roman 63 Untitled Edward Carn 65 Interview A Conversation with Kelly S. Kennedy Ron Capps 69 O-Dark-Thirty Staff Ron Capps Editor Janis Albuquerque Designer Jerri Bell Managing Editor Dario DiBattista Non-Fiction Editor Fred Foote Poetry Editor Kate Hoit Multimedia Editor (web) Jim Mathews Fiction Editor ISSN: 2325-3002 (Print) ISSN: 2325-3010 (Online) Editor’s Note e’re going to press with this edition of O-Dark-Thirty just Wa few days before the 70th Anniversary of the D-Day land- ings. -

Africa Yearbook

AFRICA YEARBOOK AFRICA YEARBOOK Volume 10 Politics, Economy and Society South of the Sahara in 2013 EDITED BY ANDREAS MEHLER HENNING MELBER KLAAS VAN WALRAVEN SUB-EDITOR ROLF HOFMEIER LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 ISSN 1871-2525 ISBN 978-90-04-27477-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-90-04-28264-3 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents i. Preface ........................................................................................................... vii ii. List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................... ix iii. Factual Overview ........................................................................................... xiii iv. List of Authors ............................................................................................... xvii I. Sub-Saharan Africa (Andreas Mehler, -

1 Statement by Christopher Fomunyoh, Ph.D. Senior Associate and Regional Director for Central and West Africa National Democrati

Statement by Christopher Fomunyoh, Ph.D. Senior Associate and Regional Director for Central and West Africa National Democratic Institute U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Subcommittee on African Affairs “Addressing Developments in Mali: Restoring Democracy and Reclaiming the North” December 5, 2012 Mr. Chairman and members of the Subcommittee, on behalf of the National Democratic Institute (NDI), I appreciate the opportunity to discuss recent political developments in Mali. Since Mali’s first steps toward democratization in the early 1990s, NDI and other U.S.-based nongovernmental organizations have worked with Malian legislators, party leaders, and civil society activists to support the country’s nascent democracy. Early this year, and with funding from USAID and other partners, NDI was providing technical assistance to citizen observers of the electoral process, fostering inter-party dialogue, and taking steps to increase the participation of women and youth in political processes. I last visited Bamako in October, and met with civic and political leaders to gauge the level of election preparations and their overall commitment to a democratic transition. Introduction Today Mali faces three interwoven crises: an on-going armed occupation of two-thirds of the country and a humanitarian emergency in the north that has displaced an estimated 450,000 people1; persistent political uncertainty in the capital, Bamako; and a severe food shortage that is affecting the entire Sahel region.2 Should Mali rebound from these crises, Malian democrats and the international community would need to better understand the reasons for the political alienation of citizens, including youth, women, and ethnic minorities from the previous democratically-elected government so as to avoid future backsliding. -

Rwanda 20 and Darfur 10

Rwanda 20 and Darfur 10 New Responses to Africa’s Mass Atrocities By John Prendergast April 2014 WWW.ENOUGHPROJECT.ORG Rwanda 20 and Darfur 10 New Responses to Africa’s Mass Atrocities* By John Prendergast April 2014 COVER PHOTO A young Rwandan girl walks through Nyaza cemetery outside Kigali, Rwanda on Monday November 25, 1996. Thousands of victims of the 1994 genocide are buried there. AP/RICARDO MAZALAN * This Enough Project report expands on an earlier argument advanced in a Foreign Affairs article entitled “The New Face of African Conflict: In Search of a Way Forward,” by John Prendergast, published March 12, 2014. Introduction As commemorations unfold honoring the 20th anniversary of the onset of Rwanda’s genocide and the 10th year after Darfur’s genocide was recognized, the rhetoric of commitment to the prevention of mass atrocities has never been stronger. Actions, unsurprisingly, have not matched that rhetoric. But the conventional diagnosis of this chasm between words and deeds – a lack of political will – only explains part of the action deficit. More deeply, international crisis response strategies in Africa have hardly evolved in the years since the Rwandan genocide erupted. Until there is a fuller recognition of the core drivers of African conflict, their cross-border nature, and the need for more nuanced and comprehensive responses, the likelihood will remain high that more and more anniversaries of mass atrocity events will have to be commemorated by future generations. Conflict drivers need to be much better understood in order to devise more relevant responses. The band of crisis and conflict spanning the Horn of Africa, East Africa, and Central Africa is ground zero for mass atrocity events globally. -

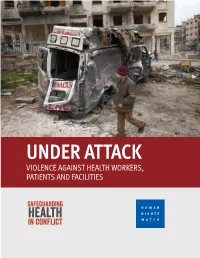

Under Attack

UNDER ATTACK V IOLEN CE A GA INST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Safeguarding HUMAN Health RIGHTS in Conflict WATCH (front cover) A Syrian youth walks past a destroyed ambulance in the Saif al-Dawla district of the war-torn northern city of Aleppo on January 12, 2013. © 2013 JM Lopez/AFP/Getty Images UNDER ATTACK VIOLENCE AGAINST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Overview of Recent Attacks on Health Care ...........................................................................................2 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 Urgent Actions Needed .......................................................................................................................7 Polio Vaccination Campaign Workers Killed ..........................................................................................8 Nigeria and Pakistan ......................................................................................................................8 Emergency Care Outlawed .................................................................................................................10 Turkey ..........................................................................................................................................10 Health Workers Arrested, Imprisoned ................................................................................................12 Bahrain ........................................................................................................................................12 -

COUNTRY ANALYSES and PLANS Niger NIGER

COUNTRY ANALYSES AND PLANS Niger NIGER $104M of CapEx funding and $96M of annual OpEx funding will enable Niger to connect over 19,000 schools This investment will bring 3.5 million students and teachers online and bring connectivity to 7.2 million community members who live locally, potentially enabling over 525 million USD of GDP growth, a 1.8% increase. Source: Dalberg Analysis based on Giga mapping and modelling data, 2020 NIGER “The Giga initiative is a great project for us because it comes to complement the already existing efforts we had of last mile connectivity to different essential services like schools.” IBRAHIMA GUIMBA-SAÏDOU Director, ANSI & Minister | Special Advisor NIGER Mobile coverage has steadily increased over the last 5 years, further connectivity is required to achieve rural development plans In the last 5 years mobile broadband coverage has grown The Government of Niger is aiming to drive economic growth through but internet use has lagged behind digitization with universal access to connectivity Broadband coverage and internet penetration, % of Niger hopes to achieve this target through the following internet population. (ITU, 2020) connectivity and education policies: 100 • Renaissance Act II Program: The President’s 2016 reform program envisages 3G Coverage an improvement in the quality of public services by improving digital Internet users1 communication within society. This led to the creation of National Agency for 80 Information Systems (ANSI) and the strategic vision "NIGER 2.0“ Airtel became the first 4G -

Global Extremism Monitor

Global Extremism Monitor Violent Islamist Extremism in 2017 WITH A FOREWORD BY TONY BLAIR SEPTEMBER 2018 1 2 Contents Foreword 7 Executive Summary 9 Key Findings About the Global Extremism Monitor The Way Forward Introduction 13 A Unifying Ideology Global Extremism Today The Long War Against Extremism A Plethora of Insurgencies Before 9/11 A Proliferation of Terrorism Since 9/11 The Scale of the Problem The Ten Deadliest Countries 23 Syria Iraq Afghanistan Somalia Nigeria Yemen Egypt Pakistan Libya Mali Civilians as Intended Targets 45 Extremist Groups and the Public Space Prominent Victims Breakdown of Public Targets Suicide Bombings 59 Use of Suicide Attacks by Group Female Suicide Bombers Executions 71 Deadliest Groups Accusations Appendices 83 Methodology Glossary About Us Notes 3 Countries Affected by Violent Islamist Extremism, 2017 4 5 6 Foreword Tony Blair One of the core objectives of the Institute is the promotion of co-existence across the boundaries of religious faith and the combating of extremism based on an abuse of faith. Part of this work is research into the phenomenon of extremism derived particularly from the abuse of Islam. This publication is the most comprehensive analysis of such extremism to date and utilises data on terrorism in a new way to show: 1. Violent extremism connected with the perversion of Islam today is global, affecting over 60 countries. 2. Now more than 120 different groups worldwide are actively engaged in this violence. 3. These groups are united by an ideology that shares certain traits and beliefs. 4. The ideology and the violence associated with it have been growing over a period of decades stretching back to the 1980s or further, closely correlated with the development of the Muslim Brotherhood into a global movement, the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and—in the same year—the storming by extremist insurgents of Islam’s holy city of Mecca.