Transnational Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Womeninscience.Pdf

Prepared by WITEC March 2015 This document has been prepared and published with the financial support of the European Commission, in the framework of the PROGRESS project “She Decides, You Succeed” JUST/2013/PROG/AG/4889/GE DISCLAIMER This publication has been produced with the financial support of the PROGRESS Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of WITEC (The European Association for Women in Science, Engineering and Technology) and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. Partners 2 Index 1. CONTENTS 2. FOREWORD5 ...........................................................................................................................................................6 3. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................7 4. PART 1 – THE CASE OF ITALY .......................................................................................................13 4.1 STATE OF PLAY .............................................................................................................................14 4.2 LEGAL FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................................18 4.3 BARRIERS AND ENABLERS .........................................................................................................19 4.4 BEST PRACTICES .........................................................................................................................20 -

Unemployment Rates in Italy Have Not Recovered from Earlier Economic

The 2017 OECD report The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle explores how gender inequalities persist in social and economic life around the world. Young women in OECD countries have more years of schooling than young men, on average, but women are less still likely to engage in paid work. Gaps widen with age, as motherhood typically has negative effects on women's pay and career advancement. Women are also less likely to be entrepreneurs, and are under-represented in private and public leadership. In the face of these challenges, this report assesses whether (and how) countries are closing gender gaps in education, employment, entrepreneurship, and public life. The report presents a range of statistics on gender gaps, reviews public policies targeting gender inequality, and offers key policy recommendations. Italy has much room to improve in gender equality Unemployment rates in Italy have not recovered from The government has made efforts to support families with earlier economic crises, and Italian women still have one childcare through a voucher system, but regional disparities of the lowest labour force participation rates in the OECD. persist. Improving access to childcare should help more The small number of women in the workforce contributes women enter work, given that Italian women do more than to Italy having one of the lowest gender pay gaps in the three-quarters of all unpaid work (e.g. care for dependents) OECD: those women who do engage in paid work are in the home. Less-educated Italian women with children likely to be better-educated and have a higher earnings face especially high barriers to paid work. -

Italy Women's Rights

October 2019 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE UPR OF ITALY WOMEN’S RIGHTS CONTENTS Context .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Gender stereotypes and discrimination ..................................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 5 Violence against women, femicide and firearms ....................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 6 VAW: prevention, protection and the need for integrated policies at the national and regional levels . 7 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 7 Violence against women: access to justice ................................................................................................ 8 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 9 Sexual and reproductive health and rights ............................................................................................. 10 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................... -

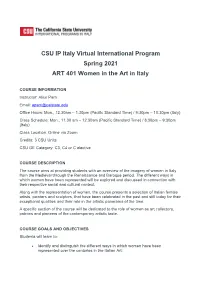

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401 Women in the Art in Italy COURSE INFORMATION Instructor: Alice Parri Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon., 12.30am – 1.30pm (Pacific Standard Time) / 9:30pm – 10:30pm (Italy) Class Schedule: Mon., 11.30 am – 12.30am (Pacific Standard Time) / 8:30pm – 9:30pm (Italy) Class Location: Online via Zoom Credits: 3 CSU Units CSU GE Category: C3, C4 or C elective COURSE DESCRIPTION The course aims at providing students with an overview of the imagery of women in Italy from the Medieval through the Renaissance and Baroque period. The different ways in which women have been represented will be explored and discussed in connection with their respective social and cultural context. Along with the representation of women, the course presents a selection of Italian female artists, painters and sculptors, that have been celebrated in the past and still today for their exceptional qualities and their role in the artistic panorama of the time. A specific section of the course will be dedicated to the role of women as art collectors, patrons and pioneers of the contemporary artistic taste. COURSE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Students will learn to: • Identify and distinguish the different ways in which women have been represented over the centuries in the Italian Art; • Outline the imagery of women in Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque period in connection with specific interpretations, meanings and functions attributed in their respective cultural context; • Recognize and discuss upon the Italian women artists; • Examine and discuss upon the role of Italian women as art collector and patrons. -

Female Immigrant in Cyprus – Profile, Obstacles, Needs, Aspirations

Female Immigrants in Cyprus – profile, obstacles, needs, aspirations Dr Despina Charalambidou-Solomi (EKIF President) Chrystalla Maouri (EKIF Vice President) Dr Natasa Economidou- Stavrou (EKIF Treasurer) Abstract This paper draws on the findings of a research project by the Cyprus Research Centre (EKIF)1 which aimed at, through the views of migrant women living and working on the island of Cyprus, sketching the profile of the economic female immigrant, identifying the drawbacks in her social and work environment and highlighting her needs for personal and professional development in order to meet her aspirations. The data was collected through the use of an anonymous, bilingual questionnaire (Greek and English) made up of closed and open-ended questions which can be classified into five thematic categories: personal details, work conditions, human/legal rights, personal and professional development and socialization. Three thousand questionnaires were distributed to female immigrants of various backgrounds on a national basis and 1702 responses were received. Collected data was analysed using SPSS. For the first time such a large female immigrant population becomes the subject of a research survey. The outcome is interesting and poses the need for further research in all thematic categories. It also contributes to the ongoing debates relating to immigration: discrimination, integration, multiculturalism and education. Female immigrants, one of the most vulnerable social groups, surprise us with their educational standard, their interests/hobbies, their aspirations and eagerness in acquiring further educational qualifications and desire to be accepted in their social milieu. These women are part of our social landscape and their views will, hopefully, contribute to the debate at an academic, research and policy level. -

TO DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Building a Support System for Victims of Domestic Violence REACT to DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

medinstgenderstudies.org © 2011, Mediterranean Institute of Gender Studies, all rights reserved. 46 Makedonitissas Ave. P.O. Box 24005, Nicosia 1703 Cyprus REACT TO DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Building a Support System for victims of Domestic Violence REACT TO DOMESTIC VIOLENCE BUILDING A SUPPORT SYSTEM FOR VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE CYPRUS MAPPING STUDY: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DOMESTIC VIOLENCE LEGISLATION, POLICIES AND THE EXISTING VICTIM SUPPORT SYSTEM DECEMBER, 2010 REACT to Domestic Violence: Building a Support System for victims of Domestic Violence © 2011, Mediterranean Institute of Gender Studies, all rights reserved. 46 Makedonitissas Ave. P.O. Box 24005, Nicosia 1703 Cyprus Authors: Christina Kaili, Susana Pavlou. Designer: Mario Pavlou, 3ems Limited. Printed and bound by Kemanes Digital Printers Ltd. This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Commission, Daphne III Programme. The content of this documents are the sole responsibility of the Mediterranean Institute of Gender Studies and the Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained herein. Charte graphique Graphic specifications Graphische karte 09/2005 tion original OIB 4 & Concept reproduction concep Contents CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 THE CASE OF CYPRUS 2 2.1 Defining Domestic Violence ............................................................................................. 2 2.2 Main Features and Recent Trends in Domestic Violence ........................................................... 3 2.3 -

Why Are Fertility and Women's Employment Rates So Low in Italy?

IZA DP No. 1274 Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca Silvia Pasqua Chiara Pronzato DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER August 2004 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca University of Turin, CHILD and IZA Bonn Silvia Pasqua University of Turin and CHILD Chiara Pronzato University of Turin and CHILD Discussion Paper No. 1274 August 2004 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 Email: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the institute. Research disseminated by IZA may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit company supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its research networks, research support, and visitors and doctoral programs. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. -

OECD EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK – ISBN 92-64-19778-8 – ©2002 62 – Women at Work: Who Are They and How Are They Faring?

Chapter 2 Women at work: who are they and how are they faring? This chapter analyses the diverse labour market experiences of women in OECD countries using comparable and detailed data on the structure of employment and earnings by gender. It begins by documenting the evolution of the gender gap in employment rates, taking account of differences in working time and how women’s participation in paid employment varies with age, education and family situation. Gender differences in occupation and sector of employment, as well as in pay, are then analysed for wage and salary workers. Despite the sometimes strong employment gains of women in recent decades, a substantial employment gap remains in many OECD countries. Occupational and sectoral segmentation also remains strong and appears to result in an under-utilisation of women’s cognitive and leadership skills. Women continue to earn less than men, even after controlling for characteristics thought to influence productivity. The gender gap in employment is smaller in countries where less educated women are more integrated into the labour market, but occupational segmentation tends to be greater and the aggregate pay gap larger. Less educated women and mothers of two or more children are considerably less likely to be in employment than are women with a tertiary qualification or without children. Once in employment, these women are more concentrated in a few, female-dominated occupations. In most countries, there is no evidence of a wage penalty attached to motherhood, but their total earnings are considerably lower than those of childless women, because mothers more often work part time. -

The Female Condition During Mussolini's and Salazar's Regimes

The Female Condition During Mussolini’s and Salazar’s Regimes: How Official Political Discourses Defined Gender Politics and How the Writers Alba de Céspedes and Maria Archer Intersected, Mirrored and Contested Women’s Role in Italian and Portuguese Society Mariya Ivanova Chokova Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Prerequisite for Honors In Italian Studies April 2013 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter I: The Italian Case – a historical overview of Mussolini’s gender politics and its ideological ramifications…………………………………………………………………………..6 I. 1. History of Ideology or Ideology of History……………………………………………7 1.1. Mussolini’s personal charisma and the “rape of the masses”…………………………….7 1.2. Patriarchal residues in the psychology of Italians: misogyny as a trait deeply embedded, over the centuries, in the (sub)conscience of European cultures……………………………...8 1.3. Fascism’s role in the development and perpetuation of a social model in which women were necessarily ascribed to a subaltern position……………………………………………10 1.4. A pressing need for a misogynistic gender politics? The post-war demographic crisis and the Role of the Catholic Church……………………………………………………………..12 1.5. The Duce comes in with an iron fist…………………………………………………….15 1.6. Fascist gender ideology and the inconsistencies and controversies within its logic…….22 Chapter II: The Portuguese Case – Salazar’s vision of woman’s role in Portuguese society………………………………………………………………………………………..28 II. 2.1. Gender ideology in Salazar’s Portugal.......................................................................29 2.2. The 1933 Constitution and the social place it ascribed to Portuguese women………….30 2.3. The role of the Catholic Church in the construction and justification of the New State’s gender ideology: the Vatican and Lisbon at a crossroads……………………………………31 2 2.4. -

Cilician Armenian Mediation in Crusader-Mongol Politics, C.1250-1350

HAYTON OF KORYKOS AND LA FLOR DES ESTOIRES: CILICIAN ARMENIAN MEDIATION IN CRUSADER-MONGOL POLITICS, C.1250-1350 by Roubina Shnorhokian A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (January, 2015) Copyright ©Roubina Shnorhokian, 2015 Abstract Hayton’s La Flor des estoires de la terre d’Orient (1307) is typically viewed by scholars as a propagandistic piece of literature, which focuses on promoting the Ilkhanid Mongols as suitable allies for a western crusade. Written at the court of Pope Clement V in Poitiers in 1307, Hayton, a Cilician Armenian prince and diplomat, was well-versed in the diplomatic exchanges between the papacy and the Ilkhanate. This dissertation will explore his complex interests in Avignon, where he served as a political and cultural intermediary, using historical narrative, geography and military expertise to persuade and inform his Latin audience of the advantages of allying with the Mongols and sending aid to Cilician Armenia. This study will pay close attention to the ways in which his worldview as a Cilician Armenian informed his perceptions. By looking at a variety of sources from Armenian, Latin, Eastern Christian, and Arab traditions, this study will show that his knowledge was drawn extensively from his inter-cultural exchanges within the Mongol Empire and Cilician Armenia’s position as a medieval crossroads. The study of his career reflects the range of contacts of the Eurasian world. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the financial support of SSHRC, the Marjorie McLean Oliver Graduate Scholarship, OGS, and Queen’s University. -

“THEY TEACH US to HATE EACH OTHER” a Study on Social Impediments for Peace-Building Interaction Between Young Cypriot Women

UMEÅ UNIVERSITY Umeå Centre for Gender Studies “THEY TEACH US TO HATE EACH OTHER” A Study on Social Impediments for Peace-Building Interaction Between Young Cypriot Women Linnéa Frändå Magister Thesis in Gender Studies Spring 2017 Advisor: Liselotte Eriksson Linnéa Frändå ABSTRACT The yet unresolved interethnic conflict on the island of Cyprus known as the ‘Cyprus Problem’ is one of the longest persisting conflicts in the world stretching over five decades. The conflict is between the Greek-Cypriots and Turkish-Cypriots and has consequently divided the Island into a Greek-Cypriot administrated southern part, and a Turkish-Cypriot administrated northern part. Despite the opening of the borders in 2003, which granted permission to cross over to each side, studies show that the peace-building interaction between the younger generations remains limited. Through in-depth interviews with ten young Cypriot women, the thesis analyses social factors impeding the interaction across the divide and provide an understanding of the women’s perception of peace in Cyprus. The politicisation of the construction of belonging continues to disconnect the women from a shared Cypriot identity and hence impedes interaction across the divide. Further, the context of the negotiations has created a stalemate on peace-building interaction for many of the women and had a negative impact on their views on politics in general. The study reaffirms that women’s political involvement is essential to bring about peace and reconciliation in Cyprus. Keywords: Cyprus, conflict, identity, politics of belonging, women, peace 2 Linnéa Frändå TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 4 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ....................................................................................................... 6 Ethnic conflict through a gendered lens ......................................................................................... -

Women Bank Shareholders in Cyprus (1913-1930): Bridging ‘Separate Spheres’ in a Family Type Economy

Women Bank Shareholders in Cyprus (1913-1930): Bridging ‘Separate Spheres’ in a Family Type Economy Magdalene Antreou1 Abstract The issues of gender and banking historiography have been poorly discussed by national literature. This paper seeks to help cover this gap and further contribute to the limited, yet very informative existing knowledge regarding the role of women in Cyprus’s historiography and economy. In addition, it aims to challenge the master narrative of ‘separate spheres’ and to discuss women’s investment activity within a family framework. For this, I have researched two bank shareholders’ ledgers from the Bank of Cyprus Historical Archive covering the period between 1913 and 1930, and the digitalised archives of ten Greek Cypriot newspapers. Keywords: women bank shareholders, women history, banking history, separate spheres, family type economy Introduction R.J. Morris, in discussing the issue of gender and property in the 17th-18th century England had argued that ‘So far women have sat at the edge of history’.2 This also applies to Cypriot women, as Myria Vassiliadou argues, ‘women have been totally hidden from Cypriot history’.3 Nevertheless, numerous scholars have found evidences of women’s economic activities dating back to the late-medieval Cyprus. Dincer had discovered that in late medieval Cyprus, ‘post marriage women could take part in setting up trading 1 Magdalene Antreou, Historian – Researcher, PhD in Political Science and History, Panteion Univer- sity of Social and Political Sciences. 2 R.J. Morris, Men, Women and Property in England, 1780-1870, A Social and Economic History of Family Strategies amongst the Leeds Middle Classes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005) 233.