Detection of Human Monkeypox in the Republic of the Congo Following Intensive Community Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repupublic of Congo

BE TOU & IMPFONDO MARKET ASSESSMENT IN LIKOUALA – REPUBLIC OF CONGO Cash Based Transfer Market This market assessment assesses the feasibility of markets in Bétou and Assessment: Impfondo to absorb and respond to a CBT intervention aimed at supporting CAR refugees’ food security in The Republic of Congo’s Likouala region. The December report explores appropriate measures a CBT intervention in Likouala would 2015 need to adopt in order to address hurdles limiting Bétou and Impfondo markets’ functionality. Contents Executive Summary: ............................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Introduction and Macro-Economic Analysis of RoC .............................................................. 5 1.1: Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2: The Economy ................................................................................................................................... 6 Section 2: Market Assessment Introduction and Methodology ............................................................. 9 2.1: Market Assessment Introduction .................................................................................................... 9 2.2: Market Assessment Methodology ................................................................................................... 9 Section 3: Limitations of the Market Assessment ............................................................................... -

Dissolved Major Elements Exported by the Congo and the Ubangui Rivers

Journal of Hydrology, 135 (1992) 237-257 237 Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam [21 Dissolved major elements exported by the Congo and the Ubangi rivers during the period 1987-1989 Jean-Luc Probst a, Renard-Roger NKounkou ~', G6rard Krempp ~, Jean-Pierre Bricquet b, Jean-Pierre Thi6baux c and Jean-Claude Olivry d ~Centre de G~ochimie de ia Surface (CNRS), I. rue Blessig, 67084 Strasbourg Cedex, France bCentre ORSTOM, B.P. 181, Brazzaville, Congo ~Centre ORSTOM. B.P. 893, Bangui. Central dfrican Republic OCentre ORSTOM, B.P. 2528. Bamako. Mali (Received 20 September 1991; accepted 6 October 1991) ABSTRACT Probst, J.-L., NKounkou, R.-R., Krempp, G., Bricquet, J.-P., Thi6baux, J.-P. and Olivry, J.-C., 1992. Dissolved major elements exported by the Congo and the Ubangi rivers during the period 1987-1989. J. Hydrol., 135: 237-257. On the basis of monthly sampling during the period 1987-1989, the geochemis:ry of ~he Congo and the Ubangi (second largest tributary of the Congo) rivers was studied in order (I) to understand the seasonal variations of the physico-chemical parameters of the waters and (2) to estimate the annual dissolved fluxes exported by the two rivers. The results presented here correspond to the first three years of measurements carried out for a scientific programme (Interdisciplinary Research Programme on Geodynamics of Peri- Atlantic lntertropical Environments, Operation 'Large River Basins' (PIRAT-GBF) undertaken jointly by lnstitut National des Sciences de l'Univers (INSU) and Institut Fran~ais de Recherche Scientifique pour ie D6veloppement en Coop6ration (ORSTOM)) planned to run for at least ten years. -

THE DOUBLE-FRANKING PERIOD ALSACE-LORRAINE, 1871-1872 by Ruth and Gardner Brown

WHOLE NUMBER 199 (Vol. 41, No.1) January 1985 USPS #207700 THE DOUBLE-FRANKING PERIOD ALSACE-LORRAINE, 1871-1872 By Ruth and Gardner Brown Introduction Ruth and I began this survey in December 1983 and 1 wrote the art:de in November] 984 after her sudden death in July. I have included her narre as an author since she helped with the work. 1 have used the singular pro noun in this article because it is painful for me to do otherwise. After buying double-franking covers for over 30 years I recently made a collection (an exhibit) out of my accumulation. In anticipation of this ef fort, about 10 years ago, I joined the Societe Philatelique Alsace-Lorraine (SPAL). Their publications are to be measured not in the number of pages but by weight! Over the years I have received 11 pounds of documents, most of it is xeroxed but in 1983 they issued a nicely printed, up to date catalogue covering the period 1872-1924. Although it is for the time frame after the double-franking era, it is the only source known to me which solves the mys teries of the name changes of French towns to German. The ones which gave me the most trouble were French: Thionville, became German Dieden l!{\fen, and Massevaux became Masmunster. One of the imaginative things done by SPAL was to offel' reduced xerox copies of 40, sixteen-page frames, exhibited at Colmar in 1974. Many of these covered the double-franking period. Before mounting my collection I decided to review the SPAL literature to get a feeling for what is common and what is rare. -

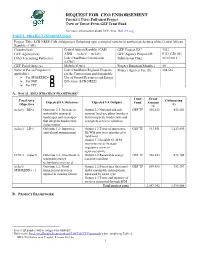

REQUEST for CEO ENDORSEMENT PROJECT TYPE: Full-Sized Project TYPE of TRUST FUND:GEF Trust Fund

REQUEST FOR CEO ENDORSEMENT PROJECT TYPE: Full-sized Project TYPE OF TRUST FUND:GEF Trust Fund For more information about GEF, visit TheGEF.org PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: LCB-NREE CAR child project: Enhancing agro-ecological systems in northern prefectures of the Central African Republic (CAR) Country(ies): Central African Republic (CAR) GEF Project ID:1 9532 GEF Agency(ies): AfDB (select) (select) GEF Agency Project ID: P-Z1-CZ0-001 Other Executing Partner(s): Lake Chad Basin Commission Submission Date: 06/16/2016 (LCBC) GEF Focal Area (s): Multifocal Area Project Duration(Months) 60 Name of Parent Program (if Lake Chad Basin Regional Program Project Agency Fee ($): 204,636 applicable): for the Conservation and Sustainable For SFM/REDD+ Use of Natural Resources and Energy For SGP Efficiency (LCB-NREE) For PPP A. FOCAL AREA STRATEGY FRAMEWORK2 Trust Grant Focal Area Cofinancing Expected FA Outcomes Expected FA Outputs Fund Amount Objectives ($) ($) (select) BD-2 Outcome 2.1: Increase in Output 2.2 National and sub- GEF TF 502,453 855,203 sustainably managed national land-use plans (number) landscapes and seascapes that incorporate biodiversity and that integrate biodiversity ecosystem services valuation conservation (select) LD-1 Outcome 1.2: Improved Output 1.2 Types of innovative GEF TF 913,551 1,113,890 agricultural management SL/WM practices introduced at field level Output 1.3 Suitable SL/WM interventions to increase vegetative cover in agroecosystems CCM-3 (select) Outcome 3.2: Investment in Output 3.2 Renewable energy GEF TF 502,453 672,100 renewable energy capacity installed technologies increased (select) Outcome 1.2: Good Output 1.2 Forest area (hectares) GEF TF 639,485 753,307 SFM/REDD+ - 1 management practices under sustainable management, applied in existing forests separated by forest type Output 1.3 Types and quantity of services generated through SFM Total project costs 2,557,942 3,394,500 B. -

Discharge of the Congo River Estimated from Satellite Measurements

Discharge of the Congo River Estimated from Satellite Measurements Senior Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Science Degree At The Ohio State University By Lisa Schaller The Ohio State University Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………..….....Page iii List of Figures ………………………………………………………………...……….....Page iv Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….....Page 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………….....Page 2 Study Area ……………………………………………………………..……………….....Page 3 Geology………………………………………………………………………………….....Page 5 Satellite Data……………………………………………....…………………………….....Page 6 SRTM ………………………………………………………...………………….....Page 6 HydroSHEDS ……………………………………………………………….….....Page 7 GRFM ……………………………………………………………………..…….....Page 8 Methods ……………………………………………………………………………..….....Page 9 Elevation ………………………………………………………………….…….....Page 9 Slopes ………………………………………………………………………….....Page 10 Width …………………………………………….…………………………….....Page 12 Manning’s n ……………………………………………………………..…….....Page 14 Depths ……………………………………………………………………...….....Page 14 Discussion ………………………………………………………………….………….....Page 15 References ……………………………….…………………………………………….....Page 18 Figures …………………………………………………………………………...…….....Page 20 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank OSU’s Climate, Water and Carbon program for their generous support of my research project. I would also like to thank NASA’s programs in Terrestrial Hydrology and in Physical Oceanography for support and data. Without Doug Alsdorf and Michael Durand, this project would -

New Influx from the Central African Republic to the DRC

AD HOC UPDATE #7: New influx from the Central African Republic to the DRC 12 February 2021 Highlights ▪ As of 12 February, DRC have reported the arrival of an estimated 92,000 individuals who fled from CAR as a result of the violence that erupted amid the December 2020 elections. ▪ As of 11 February 2021, UNHCR and CNR have biometrically registered a total of 26,137 new arrivals from CAR. ▪ From 1-3 February, a joint mission by the Resident Representative/Humanitarian coordinator, the Government, UN agencies and NGOs was scheduled to travel to North Ubangi to assess the situation. UNHCR Representative Liz Ahua participating in the distribution of core relief items to some of the most vulnerable refugees in Yakoma North Ubangi ▪ UNHCR is biometrically registering up to 1,000 Province, DRC. © UNHCR/Gemund new arrivals per day. L2 Emergency Declaration On 21 January, a Level 2 emergency has been declared for the UNHCR Operation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This decision is designed to scale up UNHCR operations’ preparedness and response activities in addressing the protection needs of refugees and other populations affected by the new crisis. I- SITUATION • Elections Presidential and legislative elections were held on 27 December 2020 in the Central African Republic (CAR) in a tense security context characterized by sporadic violence. Several armed groups, most of them, signatories of the February 2019 peace agreement, called off a ceasefire and merged into the Coalition of Patriots for Change (CPC). They resumed military operations against the government, carrying out deadly attacks in major towns including on the outskirts of the capital Bangui. -

2.5 Democratic Republic of Congo Waterways Assessment

2.5 Democratic Republic of Congo Waterways Assessment Company Information Travel Time Matrix Key Routes Below is a map of how waterways connect with railways in the Democratic Republic of Congo: The waterway network in the Democratic Republic of Congo has always been a key factor in the development of the country: the strategic use of its richness allows many possibilities in terms of transportation and electricity production. Below is a map of the ports and waterways network in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Page 1 The navigation network of inland waterways of the Democratic Republic of Congo totals more or less 16,000 km in length and is based on the Congo River and its major lakes. It is divided into four sections, called navigable reach, often connected by rail, including: The lower reach of the Congo River or the maritime in the west which totals 140 km from Banana (mouth) to the port of Matadi; The middle reach in the north and center of the Congo River Basin with its two axes (Kisangani-Kwamouth and Ilebo-Kwamouth) including two lakes (Maindombe and Tumba) and leading to Kinshasa; The upper reach in the east that goes from Ubundu to Province Orientale up to Lake Moero (Katanga Province) with two main axes Ubundu- Kindu and Kongolo-Bukama; The chain of lakes comprised of lakes Mweru, Tanganyika, Kivu, Edward and Albert. Until recently, management of inland navigation was carried out efficiently by the Board of Maritime Routes (RVM) on maritime reach and by the Board of Fluvial Routes (RVF) in the middle and upper reaches of Congo River. -

'Cuvette Centrale' of the Congo River Basin Using the SWAT Hydrological Model

water Article Sediment Balance Estimation of the ‘Cuvette Centrale’ of the Congo River Basin Using the SWAT Hydrological Model Pankyes Datok 1,*, Sabine Sauvage 1,* , Clément Fabre 2 , Alain Laraque 3, Sylvain Ouillon 4,5 , Guy Moukandi N’kaya 6 and José-Miguel Sanchez-Perez 1 1 Laboratoire Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Environnement, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, INPT, UPS, 31326 Toulouse, France; [email protected] 2 Eawag, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, CH-8600 Dübendorf, Switzerland; [email protected] 3 GET, UMR CNRS/IRD/UPS, 31400 Toulouse, France; [email protected] 4 LEGOS, Université de Toulouse, IRD, CNRS, CNES, UPS, 31400 Toulouse, France; [email protected] 5 USTH, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST), Hanoi 100000, Vietnam 6 LMEI/CUSI/ENSP/Université Marien Ngouabi, Brazzaville BP 69, Congo; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.D.); [email protected] (S.S.) Abstract: In this study, the SWAT hydrological model was used to estimate the sediment yields in the principal drainage basins of the Congo River Basin. The model was run for the 2000–2012 period and calibrated using measured values obtained at the basins principal gauging station that controls 98% of the basin area. Sediment yield rates of 4.01, 5.91, 7.88 and 8.68 t km−2 yr−1 were estimated for Citation: Datok, P.; Sauvage, S.; the areas upstream of the Ubangi at Bangui, Sangha at Ouesso, Lualaba at Kisangani, and Kasai at Fabre, C.; Laraque, A.; Ouillon, S.; Kuto-Moke, respectively—the first three of which supply the Cuvette Centrale. -

Handbook of Ethnography

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Wellesley College Library http://www.archive.org/details/handbookofethnogOOIeyb PUBLISHED ON THE LOUIS STERN MEMORIAL FUND HANDBOOK OF ETHNOGRAPHY BY JAMES G. LEYBURN Assistant Professor of the Science of Society in Yale University NEW HAVEN YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON . HUMPHREY MILFORD • OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1931 Copyright 1931 by Yale University Press Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. This book may not be re- produced, in whole or in part, in any form, ex- cept by written permission from the publishers. n PREFACE In any science the study of simple factors aids in the comprehen- sion of the complex. Especially is this true in the study of human society, for modern phenomena are so complicated that they are all but incomprehensible except when viewed in the light of their evolution. Immediately upon his return to simpler societies, how- ever, the reader meets the names of peoples and tribes unfamiliar to him : he has but vague ideas as to the location of the Hottentots, the Veddahs, and the Yakuts ; yet the more deeply he pursues his studies, the more acutely he feels the needs of some vade mecum to tell him who these people are and where they live. This Handbook of Ethnography is designed not only for the trained ethnologist, who cannot be expected to retain in his mem- ory more than a fraction of the tribal names included herein, but for the students in allied fields—in anthropology, archaeology, the science of society (sociology), political science, and the like. -

Urban Growth and Deforestation by Remote Sensing in the Humid Tropical Forest of Congo Bassin: Case of Impfondo in Republic of Congo

American Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development Vol. 3, No. 3, 2018, pp. 46-54 http://www.aiscience.org/journal/ajesd Urban Growth and Deforestation by Remote Sensing in the Humid Tropical Forest of Congo Bassin: Case of Impfondo in Republic of Congo Stoffenne Binsangou 1, Suspense Averti Ifo 1, *, Lypsia Ibocko 1, Lisa Louvouandou 1, Mesmin Tchindjang 3, Félix Koubouana 2 1Laboratory of Geomatic and Applied Tropical Ecology, Higher Normal School, University of Marien N’GOUABI, Brazzaville, Congo 2Laboratory of Geomatic and Applied Tropical Ecology, Higher National School of Forestry and Agriculture, University of Marien N’GOUABI, Brazzaville, Congo 3Department of Geography, University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé, Cameroon Abstract Urban growth is identified as one of the main deforestation drivers and land degradation in tropical region. Very few data exist to quantify the impact of this drivers. The aims of this study were: (i) estimating the activity data of the growth of the city’s Impfondo in the period between 1986 to 2016; (ii) determining the indirect drivers of that urban growth. This study is carried out in Impfondo. The remote sensing and GIS techniques were used to assess urban growth and its impact on deforestation and degradation of the forest around and in Impfondo the period between 1986 and 2016. Landsat images were used; specially 2 images Thematic Mapper (TM) of 1986 and Operational Land Imager (OLI) of 2016. ERDAS 2014 software was for images classification, classification and calculation of forest lost area during this growth. Additional field survey was made to collect truth GPS ground points. As result, the urban tram area growth from 267.86 ha in the year 1986 to 859.68 ha in the year 2016. -

The Status and Distribution of Freshwater Biodiversity in Central Africa

THE S THE STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION T A OF FRESHWATER BIODIVERSITY T U S IN CENTRAL AFRICA AND Brooks, E.G.E., Allen, D.J. and Darwall, W.R.T. D I st RIBU T ION OF F RE S HWA T ER B IODIVER S I T Y IN CEN CENTRAL AFRICA CENTRAL T RAL AFRICA INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE WORLD HEADQUARTERS Rue Mauverney 28 1196 Gland Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 999 0000 Fax: + 41 22 999 0020 www.iucn.org/species www.iucnredlist.org The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM Regional Assessment About IUCN IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ – Regional Assessment IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development Africa challenges. The Status and Distribution of Freshwater Biodiversity in Eastern Africa. Compiled by William R.T. Darwall, Kevin IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, human livelihoods and greening the world economy by supporting scientific research, managing G. Smith, Thomas Lowe and Jean-Christophe Vié, 2005. field projects all over the world, and bringing governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. The Status and Distribution of Freshwater Biodiversity in Southern Africa. Compiled by William R.T. Darwall, IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, Kevin G. Smith, Denis Tweddle and Paul Skelton, 2009. with more than 1,000 government and NGO members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over The Status and Distribution of Freshwater Biodiversity in Western Africa. -

Convergence and the Retention of Marked Consonants in Sango: the Creation and Appropriation of a Pidgin

CONVERGENCE AND THE RETENTION OF MARKED CONSONANTS IN SANGO: THE CREATION AND APPROPRIATION OF A PIDGIN William J. Samarin University of Toronto, Emeritus 1. Introduction In Uriel Weinreich’s pioneering book, Languages in contact, a work to which many are indebted (I read it more than fifty years ago at the suggestion of André Martinet, editor of Word, after I had submitted a paper on Pidgin Sango, discussed again here), languages are said to be “in contact” “if they are used alternately by the same persons.” For him contact appears to have been a cognitive phenomenon, because “the locus of contact” is language-using individuals (1953:1). And he quotes approvingly the statement, in a slightly different context, that “In the last analysis, it is individuals who respond to and influence one another. Individuals are the dynamic centers of the process of interaction” (1953:6fn18) For some research, such a psychological perspective is a necessary one, but for my study of the creation of Sango a social perspective is also required.1 (Every perspective possible should be used, a truth evident in the number of approaches that have appeared in theoretical linguistics since the ‘eclipsing’ emergence of generative grammar in the 1960’s.) In this present work I focus on data that are called historical as well as on data that are linguistic. They are the coordinates whose convergence in a certain place and time leads to an understanding of what happened in what we call contact, in this case the abrupt, disorderly, and brief interaction of persons with extremely different linguistic histories.