Health Service Provision in the Central African Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

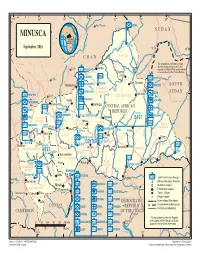

MINUSCA Aoukal S U D a N

14 ° 16 ° 18 ° 20 ° 22 ° 24 ° 26 ° Am Timan ZAMBIA é MINUSCA Aoukal S U D A N t CENTRAL a lou AFRICAN m B u a REPUBLIC a O l h r a r Birao S h e September 2016 a l r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° ° a a B b C h VAKAGAVAVAKAKAGA a r C H A D i The boundaries and names shown Garba and the designations used on this Sarh HQ Sector Center map do not imply official endorsement ouk ahr A Ouanda or acceptance by the United Nations. B Djallé PAKISTAN UNPOL Doba HQ Sector East Sam Ouandja BANGLADESH Ndélé K S O U T H Maïkouma o MOROCCO t BAMINGUIBAMBAMINAMINAMINGUINGUIGUI t o BANGLADESH BANGORANBABANGBANGORNGORNGORANORAN S U D A N BENIN 8° Sector West Kaouadja 8° HQ Goré HAUTE-KOTTOHAHAUTHAUTE-HAUTE-KOUTE-KOE-KOTTKOTTO i u a g PAKISTAN n Kabo i CAMBODIA n i n i V BANGLADESH i u b b g i Markounda i Bamingui n r UNPOL r UNPOL i CENTRAL AFRICAN G G RWANDA Batangafo m NIGER a REPUBLIC Paoua B Sector CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro SRI LANKA PERU OUHAMOUOUHAHAM Yangalia EAST m NANANA -P-PEN-PENDÉENDÉ a Mbrès OUAKOUOUAKAAKA UNPOL h u GRGRÉBGRÉBIZGRÉBIZIÉBIZI UNPOL HAUT-HAHAUTUT- FPU CAMEROON 1 Bossangoa O ka MBOMOUMBMBOMOMOU a MAURITANIA o Bouca u Dékoa Bria Yalinga k Dékoa n O UNPOL i Bozoum OUHAMOUOUHAHAM h Ippy C Sector UNPOL i Djéma 6 BURUNDI r 6 ° a ° Bambari b Bouar CENTER rra Baoro M Oua UNPOL Baboua Baoro Sector Sibut NANA-MAMBÉRÉNANANANANA-MNA-MNA-MAM-MAMBÉAMBÉAMBÉRÉBÉRÉ Grimari Bakouma MBOMOUMBMBOMOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KÉMKKÉMOÉMO m Bossembélé M b angúi bo er OMOMBEOMBELLOMBELLA-MPOKOBELLA-BELLYalokeYaloYaLLA-MPLLA-lokeA-MPOKA-MPMPOKOOKO ub UNPOL mo e O -

Central African Republic Emergency Update #2

Central African Republic Emergency Update #2 Period Covered 18-24 December 2013 [1] Highlights There are currently some 639,000 internally displaced people in the Central African Republic (CAR), including more than 210,000 in Bangui in over 40 sites. UNHCR submitted a request to the Humanitarian Coordinator for the activation of the Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster. Since 14 December, UNHCR has deployed twelve additional staff to Bangui to support UNHCR’s response to the current IDP crisis. Some 1,200 families living at Mont Carmel, airport and FOMAC/Lazaristes Sites were provided with covers, sleeping mats, plastic sheeting, mosquito domes and jerrycans. About 50 tents were set up at the Archbishop/Saint Paul Site and Boy Rabe Monastery. From 19 December to 20 December, UNHCR together with its partners UNICEF and ICRC conducted a rapid multi- sectoral assessment in IDP sites in Bangui. Following the declaration of the L3 Emergency, UNHCR and its partners have started conducting a Multi- Cluster/Sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) in Bangui and the northwest region. [2] Overview of the Operation Population Displacement 2013 Funding for the Operation Funded (42%) Funding Gap (58%) Total 2013 Requirements: USD 23.6M Partners Government agencies, 22 NGOs, FAO, BINUCA, OCHA, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. For further information, please contact: Laroze Barrit Sébastien, Phone: 0041-79 818 80 39, E-mail: [email protected] Central African Republic Emergency Update #2 [2] Major Developments Timeline of the current -

Central-African-Republic-COVID-19

Central African Republic Coronavirus (COVID-19) Situation Report n°7 Reporting Period: 1-15 July 2020 © UNICEFCAR/2020/A.JONNAERT HIGHLIGHTS As of 15 July, the Central African Republic (CAR) has registered 4,362 confirmed cases of COVID-19 within its borders - 87% of which are local Situation in Numbers transmissions. 53 deaths have been reported. 4,362 COVID-19 In this reporting period results achieved by UNICEF and partners include: confirmed cases* • Water supplied to 4,000 people in neighbourhoods experiencing acute 53 COVID-19 deaths* shortages in Bangui; *WHO/MoHP, 15 July 2020 • 225 handwashing facilities set up in Kaga Bandoro, Sibut, Bouar and Nana Bakassa for an estimate of 45,000 users per day; 1.37 million • 126 schools in Mambere Kadei, 87 in Nana-Mambere and 7 in Ouaka estimate number of prefectures equipped with handwashing stations to ensure safe back to children affected by school to final year students; school closures • 9,750 children following lessons on the radio; • 3,099 patients, including 2,045 children under 5 received free essential million care; US$ 29.5 funding required • 11,189 children aged 6-59 months admitted for treatment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) across the country; UNICEF CAR’s • 1,071 children and community members received psychosocial support. COVID-19 Appeal US$ 26 million Situation Overview & Humanitarian Needs As of 15 July, the Central African Republic (CAR) has registered 4,362 confirmed cases of COVID-19 within its borders - which 87% of which are local transmissions. 53 deaths have been reported. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a decrease in number of new cases does not mean an improvement in the epidemiological situation. -

THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC and Small Arms Survey by Eric G

SMALL ARMS: A REGIONAL TINDERBOX A REGIONAL ARMS: SMALL AND REPUBLIC AFRICAN THE CENTRAL Small Arms Survey By Eric G. Berman with Louisa N. Lombard Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] w www.smallarmssurvey.org THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND SMALL ARMS A REGIONAL TINDERBOX ‘ The Central African Republic and Small Arms is the most thorough and carefully researched G. Eric By Berman with Louisa N. Lombard report on the volume, origins, and distribution of small arms in any African state. But it goes beyond the focus on small arms. It also provides a much-needed backdrop to the complicated political convulsions that have transformed CAR into a regional tinderbox. There is no better source for anyone interested in putting the ongoing crisis in its proper context.’ —Dr René Lemarchand Emeritus Professor, University of Florida and author of The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa ’The Central African Republic, surrounded by warring parties in Sudan, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, lies on the fault line between the international community’s commitment to disarmament and the tendency for African conflicts to draw in their neighbours. The Central African Republic and Small Arms unlocks the secrets of the breakdown of state capacity in a little-known but pivotal state in the heart of Africa. It also offers important new insight to options for policy-makers and concerned organizations to promote peace in complex situations.’ —Professor William Reno Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University Photo: A mutineer during the military unrest of May 1996. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Central African Republic Situation Report No. 49 | 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC (CAR) Situation Report No. 49 (as of 4 March 2015) This report is produced by OCHA CAR in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period between 18 February and 4 March 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 18 March 2015. Highlights Some 50,000 people were displaced by ongoing insecurity and violent attacks throughout the country. Attacks against humanitarian workers continued unabated, forcing the suspension of basic services in some areas. Reports of attacks and human rights abuses against IDPs prompted serious concerns. The humanitarian community appealed for the respect of the principle of freedom of movement, especially of stranded IDPs. 436,300 10% 4.6 IDPs in CAR, Funding available million including US$61.3 million Population against the SRP of CAR 49,113 2015 requirements 2.7 Sources: UNDSS, OCHA, CCCM and UNHCR in 35 sites of $613 million) million Bangui (as of People 4 March) who need assistance Situation Overview The humanitarian situation in CAR remains extremely volatile. Insecurity and violent attacks persisted throughout the country during the reporting period, prompting new waves of displacement. Attacks against humanitarian workers continued. On 20 February, armed men attacked an INGO’s convoy on the road to Sibut from Dekoa (Kemo Province). There were no casualties, but the attackers looted at least 150 UNICEF school bags and passengers’ personal belongings. On 18 February, in the second incident on the same road in the past month, two armed men attacked an INGO in Batangafo. They took passengers’ money and telephones. -

State of Anarchy Rebellion and Abuses Against Civilians

September 2007 Volume 19, No. 14(A) State of Anarchy Rebellion and Abuses against Civilians Executive Summary.................................................................................................. 1 The APRD Rebellion............................................................................................ 6 The UFDR Rebellion............................................................................................ 6 Abuses by FACA and GP Forces........................................................................... 6 Rebel Abuses....................................................................................................10 The Need for Protection..................................................................................... 12 The Need for Accountability .............................................................................. 12 Glossary.................................................................................................................18 Maps of Central African Republic ...........................................................................20 Recommendations .................................................................................................22 To the Government of the Central African Republic ............................................22 To the APRD, UFDR and other rebel factions.......................................................22 To the Government of Chad...............................................................................22 To the United Nations Security -

ACTIVE USG HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMS in CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Last Updated 11/21/14

ACTIVE USG HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMS IN CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Last Updated 11/21/14 COUNTRYWIDE PROGRAM KEY FAO USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP SUDAN State/PRM IFRC VAKAGA Agriculture and Food Security IOM Am Dafok IMC Birao Economic Recovery and Market NetHope CHAD Systems OCHA Evacuation and On-arrival Assistance Food Assistance UNDSS BAMINGUI-BANGORAN VAKAGA Food Vouchers UNHAS DRC Health UNICEF OUHAM Garba Humanitarian Air Service WFP ACF HAUTE-KOTTO Ouanda Djalle Humanitarian Coordination IMC WHO CRS and Information Management UNICEF DRC Locally and Regionally Procured Food Ndele Ouandjia WFP IMC Logistics and Relief Commodities ICRC Mentor BAMINGUI-BANGORAN Ouadda Multi-Sector Assistance Kadja IOM Nutrition UNHCR Protection Bamingui HAUTE-KOTTO WFP NANA- Boulouba Refugee Assistance Paoua Batangafo GRIBIZI OUHAM-PENDÉ Shelter and Settlements Kaga Bandoro ACTED Bocaranga OUHAM Yangalia Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene OUAKA DRC OUHAM- Bossangoa IMC Bria Yalinga IRC PENDÉ Bouca HAUT-MBOMOU SOUTH Bozoum Dekoa Mentor SUDAN KÉMO Ippy Djema Bouar NRC OUAKA Baboua Grimari Sibut Bakouma NANA- Bambari MAMBÉRÉ Baoro Bogangolo MBOMOU KÉMO Obo NANA-MAMBÉRÉ Yaloke Bossembele Mingala SC/US BASSE- Rafai OMBELLA OMBELLA M’POKO Kouango Carnot Djomo KOTTO Zemio HAUT-MBOMOU M'POKO World Vision Bangassou MBOMOU SC/US N MAMBÉRÉ-KADEÏ Mobaye Berberati Boda Bimbo Bangui Mercy Corps Gamboula Ouango OO LOBAYE BANGUI R Soso MAMBÉRÉ-KADEÏ Mbaiki ACTED NRC Nola Regional Assistance to People Fleeing CAR SANGHA- LOBAYE CAME MBAÉRÉ Tearfund DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC WFP LWF OF THE CONGO CARE Mentor CSSI UNFPA INFORMA IC TI PH O REPUBLIC A N R U IMC UNHCR G N O I T E 0 50 100 mi G OF THE IOM UNICEF U S A A D CONGO 0 50 100 150 km I F IRC WHO D O / D C H A /. -

Location Indicators by Indicator

ECCAIRS 4.2.6 Data Definition Standard Location Indicators by indicator The ECCAIRS 4 location indicators are based on ICAO's ADREP 2000 taxonomy. They have been organised at two hierarchical levels. 12 January 2006 Page 1 of 251 ECCAIRS 4 Location Indicators by Indicator Data Definition Standard OAAD OAAD : Amdar 1001 Afghanistan OAAK OAAK : Andkhoi 1002 Afghanistan OAAS OAAS : Asmar 1003 Afghanistan OABG OABG : Baghlan 1004 Afghanistan OABR OABR : Bamar 1005 Afghanistan OABN OABN : Bamyan 1006 Afghanistan OABK OABK : Bandkamalkhan 1007 Afghanistan OABD OABD : Behsood 1008 Afghanistan OABT OABT : Bost 1009 Afghanistan OACC OACC : Chakhcharan 1010 Afghanistan OACB OACB : Charburjak 1011 Afghanistan OADF OADF : Darra-I-Soof 1012 Afghanistan OADZ OADZ : Darwaz 1013 Afghanistan OADD OADD : Dawlatabad 1014 Afghanistan OAOO OAOO : Deshoo 1015 Afghanistan OADV OADV : Devar 1016 Afghanistan OARM OARM : Dilaram 1017 Afghanistan OAEM OAEM : Eshkashem 1018 Afghanistan OAFZ OAFZ : Faizabad 1019 Afghanistan OAFR OAFR : Farah 1020 Afghanistan OAGD OAGD : Gader 1021 Afghanistan OAGZ OAGZ : Gardez 1022 Afghanistan OAGS OAGS : Gasar 1023 Afghanistan OAGA OAGA : Ghaziabad 1024 Afghanistan OAGN OAGN : Ghazni 1025 Afghanistan OAGM OAGM : Ghelmeen 1026 Afghanistan OAGL OAGL : Gulistan 1027 Afghanistan OAHJ OAHJ : Hajigak 1028 Afghanistan OAHE OAHE : Hazrat eman 1029 Afghanistan OAHR OAHR : Herat 1030 Afghanistan OAEQ OAEQ : Islam qala 1031 Afghanistan OAJS OAJS : Jabul saraj 1032 Afghanistan OAJL OAJL : Jalalabad 1033 Afghanistan OAJW OAJW : Jawand 1034 -

Central African Republic: Floods

DREF operation n° MDRCF007 Central African Republic: GLIDE n° FL-2010-000168-CAF Floods 26 August, 2010 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent emergency response. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. CHF 145,252 (USD 137,758 or EUR 104,784) has been allocated from the IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Central African Red Cross Society (CARCS) in delivering immediate assistance to some 330 displaced families, i.e. 1,650 beneficiaries. Un- earmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: The rainy season that started in July in Central African Republic (CAR) reached its peak on 7 August, 2010 when torrential rains caused serious floods in Bossangoa, a Northern Evaluation of the situation in Bossangoa by CAR Red locality situated 350 km from Bangui, the capital Cross volunteers / Danielle L. Ngaissio, CAR Red Cross city. Other neighbouring localities such as Nanga- Boguila and Kombe, located 187 and 20 km respectively from Bossangoa have also been affected. Damages registered include the destruction of 587 houses (330 completely), the destruction of 1,312 latrines, the contamination of 531 water wells by rain waters and the content of the latrines that have been destroyed. About 2,598 people (505 families) have been affected by the floods. -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Central African Republic: Who Has a Sub-Office/Base Where? (05 May 2014)

Central African Republic: Who has a Sub-Office/Base where? (05 May 2014) LEGEND DRC IRC DRC Sub-office or base location Coopi MSF-E SCI MSF-E SUDAN DRC Solidarités ICRC ICDI United Nations Agency PU-AMI MENTOR CRCA TGH DRC LWF Red Cross and Red Crescent MSF-F MENTOR OCHA IMC Movement ICRC Birao CRCA UNHCR ICRC MSF-E CRCA International Non-Governmental OCHA UNICEF Organization (NGO) Sikikédé UNHCR CHAD WFP ACF IMC UNDSS UNDSS Tiringoulou CRS TGH WFP UNFPA ICRC Coopi MFS-H WHO Ouanda-Djallé MSF-H DRC IMC SFCG SOUTH FCA DRC Ndélé IMC SUDAN IRC Sam-Ouandja War Child MSF-F SOS VdE Ouadda Coopi Coopi CRCA Ngaounday IMC Markounda Kabo ICRC OCHA MSF-F UNHCR Paoua Batangafo Kaga-Bandoro Koui Boguila UNICEF Bocaranga TGH Coopi Mbrès Bria WFP Bouca SCI CRS INVISIBLE FAO Bossangoa MSF-H CHILDREN UNDSS Bozoum COHEB Grimari Bakouma SCI UNFPA Sibut Bambari Bouar SFCG Yaloké Mboki ACTED Bossembélé ICRC MSF-F ACF Obo Cordaid Alindao Zémio CRCA SCI Rafaï MSF-F Bangassou Carnot ACTED Cordaid Bangui* ALIMA ACTED Berbérati Boda Mobaye Coopi CRS Coopi DRC Bimbo EMERGENCY Ouango COHEB Mercy Corps Mercy Corps CRS FCA Mbaïki ACF Cordaid SCI SCI IMC Batalimo CRS Mercy Corps TGH MSF-H Nola COHEB Mercy Corps SFCG MSF-CH IMC SFCG COOPI SCI MSF-B ICRC SCI MSF-H ICRC ICDI CRS SCI CRCA ACF COOPI ICRC UNHCR IMC AHA WFP UNHCR AHA CRF UNDSS MSF-CH OIM UNDSS COHEB OCHA WFP FAO ACTED DEMOCRATIC WHO PU-AMI UNHCR UNDSS WHO CRF MSF-H MSF-B UNFPA REPUBLIC UNICEF UNICEF 50km *More than 50 humanitarian organizations work in the CAR with an office in Bangui. -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House.