Contact and Creation 07 03.30

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium Language Contact and the Dynamics of Language: Theory and Implications 10-13 May 2007 Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig)

Symposium Language Contact and the Dynamics of Language: Theory and Implications 10-13 May 2007 Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig) ABSTRACTS Peter Bakker Rethinking II Certain types of syntactic and morphological features can be diffused, as in (Aarhus structural convergence and metatypy, where languages take over such properties from University) diffusion. neighboring languages. In my paper I would like to explore the idea that typological similarities in the realm of morphology can be used for establishing historical, perhaps even genetic, connections between language families with complex morphological systems. I will exemplify this with North America, in particular the possible connections between the language families of the Northwest coast/ Plateau and those of the eastern part of the Americas. I will argue on the basis on typological similarities, that (ancestor languages of) some families (notably Algonquian) spoken today east of the continental divide, were once spoken west of the continental divide. This will lead to a more theoretical discussion about diffusion: is it really possible that more abstract morphological features such as morpheme ordering can be diffused? As this appears to be virtually undocumented, we have to be very skeptical about such diffusion. This means that mere morphological similarities between morphologically complex languages should be taken as evidence for inheritance rather than the result of contact. Cécile Canut Parole et III Si la notion de contact, en sociolinguistique -

On Numeral Complexity in Hunter-Gatherer Languages

On numeral complexity in hunter-gatherer languages PATIENCE EPPS, CLAIRE BOWERN, CYNTHIA A. HANSEN, JANE H. HILL, and JASON ZENTZ Abstract Numerals vary extensively across the world’s languages, ranging from no pre- cise numeral terms to practically infinite limits. Particularly of interest is the category of “small” or low-limit numeral systems; these are often associated with hunter-gatherer groups, but this connection has not yet been demonstrated by a systematic study. Here we present the results of a wide-scale survey of hunter-gatherer numerals. We compare these to agriculturalist languages in the same regions, and consider them against the broader typological backdrop of contemporary numeral systems in the world’s languages. We find that cor- relations with subsistence pattern are relatively weak, but that numeral trends are clearly areal. Keywords: borrowing, hunter-gatherers, linguistic area, number systems, nu- merals 1. Introduction Numerals are intriguing as a linguistic category: they are lexical elements on the one hand, but on the other they are effectively grammatical in that they may involve a generative system to derive higher values, and they interact with grammatical systems of quantification. Numeral systems are particularly note- worthy for their considerable crosslinguistic variation, such that languages may range from having no precise numeral terms at all to having systems whose limits are practically infinite. As Andersen (2005: 26) points out, numerals are thus a “liminal” linguistic category that is subject to cultural elaboration. Recent work has called attention to this variation among numeral systems, particularly with reference to systems having very low limits (for example, see Evans & Levinson 2009, D. -

Repupublic of Congo

BE TOU & IMPFONDO MARKET ASSESSMENT IN LIKOUALA – REPUBLIC OF CONGO Cash Based Transfer Market This market assessment assesses the feasibility of markets in Bétou and Assessment: Impfondo to absorb and respond to a CBT intervention aimed at supporting CAR refugees’ food security in The Republic of Congo’s Likouala region. The December report explores appropriate measures a CBT intervention in Likouala would 2015 need to adopt in order to address hurdles limiting Bétou and Impfondo markets’ functionality. Contents Executive Summary: ............................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Introduction and Macro-Economic Analysis of RoC .............................................................. 5 1.1: Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2: The Economy ................................................................................................................................... 6 Section 2: Market Assessment Introduction and Methodology ............................................................. 9 2.1: Market Assessment Introduction .................................................................................................... 9 2.2: Market Assessment Methodology ................................................................................................... 9 Section 3: Limitations of the Market Assessment ............................................................................... -

MANDE LANGUAGES INTRODUCTION Mande Languages

Article details Article author(s): Dmitry Idiatov Table of contents: Introduction General Overviews Textbooks Bibliographies Journals and Book Series Conferences Text Collections and Corpora Classifications Historical and Comparative Linguistics Western Mande Central Mande Southwestern Mande and Susu- Yalunka Soninke-Bozo, Samogo, and Bobo Southeastern Mande Eastern Mande Southern Mande Phonetics Phonology Morphosyntax Morphology Syntax Language Contact and Areal Linguistics Writing Systems MANDE LANGUAGES INTRODUCTION Mande languages are spoken across much of inland West Africa up to the northwest of Nigeria as their eastern limit. The center of gravity of the Mande-speaking world is situated in the southwest of Mali and the neighboring regions. There are approximately seventy Mande languages. Mande languages have long been recognized as a coherent group. Thanks to both a sufficient number of clear lexical correspondences and the remarkable uniformity in basic morphosyntax, the attribution of a given language to Mande is usually straightforward. The major subdivision within Mande is between Western Mande, which comprises the majority of both languages and speakers, and Southeastern Mande (aka Southern Mande or Eastern Mande, which are also the names for the two subbranches of Southeastern Mande), a comparatively small but linguistically diverse and geographically dispersed group. Traditionally, Mande languages have been classified as one of the earliest offshoots of Niger-Congo. However, their external affiliation still remains a working hypothesis rather than an established fact. One of the most well-known Mande languages is probably Bamana (aka Bambara), as well as some of its close relatives, which in nonlinguistic publications are sometimes indiscriminately referred to as Mandingo. Mande languages are written in a variety of scripts ranging from Latin-based or Arabic-based alphabets to indigenously developed scripts, both syllabic and alphabetic. -

Dissolved Major Elements Exported by the Congo and the Ubangui Rivers

Journal of Hydrology, 135 (1992) 237-257 237 Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam [21 Dissolved major elements exported by the Congo and the Ubangi rivers during the period 1987-1989 Jean-Luc Probst a, Renard-Roger NKounkou ~', G6rard Krempp ~, Jean-Pierre Bricquet b, Jean-Pierre Thi6baux c and Jean-Claude Olivry d ~Centre de G~ochimie de ia Surface (CNRS), I. rue Blessig, 67084 Strasbourg Cedex, France bCentre ORSTOM, B.P. 181, Brazzaville, Congo ~Centre ORSTOM. B.P. 893, Bangui. Central dfrican Republic OCentre ORSTOM, B.P. 2528. Bamako. Mali (Received 20 September 1991; accepted 6 October 1991) ABSTRACT Probst, J.-L., NKounkou, R.-R., Krempp, G., Bricquet, J.-P., Thi6baux, J.-P. and Olivry, J.-C., 1992. Dissolved major elements exported by the Congo and the Ubangi rivers during the period 1987-1989. J. Hydrol., 135: 237-257. On the basis of monthly sampling during the period 1987-1989, the geochemis:ry of ~he Congo and the Ubangi (second largest tributary of the Congo) rivers was studied in order (I) to understand the seasonal variations of the physico-chemical parameters of the waters and (2) to estimate the annual dissolved fluxes exported by the two rivers. The results presented here correspond to the first three years of measurements carried out for a scientific programme (Interdisciplinary Research Programme on Geodynamics of Peri- Atlantic lntertropical Environments, Operation 'Large River Basins' (PIRAT-GBF) undertaken jointly by lnstitut National des Sciences de l'Univers (INSU) and Institut Fran~ais de Recherche Scientifique pour ie D6veloppement en Coop6ration (ORSTOM)) planned to run for at least ten years. -

THE DOUBLE-FRANKING PERIOD ALSACE-LORRAINE, 1871-1872 by Ruth and Gardner Brown

WHOLE NUMBER 199 (Vol. 41, No.1) January 1985 USPS #207700 THE DOUBLE-FRANKING PERIOD ALSACE-LORRAINE, 1871-1872 By Ruth and Gardner Brown Introduction Ruth and I began this survey in December 1983 and 1 wrote the art:de in November] 984 after her sudden death in July. I have included her narre as an author since she helped with the work. 1 have used the singular pro noun in this article because it is painful for me to do otherwise. After buying double-franking covers for over 30 years I recently made a collection (an exhibit) out of my accumulation. In anticipation of this ef fort, about 10 years ago, I joined the Societe Philatelique Alsace-Lorraine (SPAL). Their publications are to be measured not in the number of pages but by weight! Over the years I have received 11 pounds of documents, most of it is xeroxed but in 1983 they issued a nicely printed, up to date catalogue covering the period 1872-1924. Although it is for the time frame after the double-franking era, it is the only source known to me which solves the mys teries of the name changes of French towns to German. The ones which gave me the most trouble were French: Thionville, became German Dieden l!{\fen, and Massevaux became Masmunster. One of the imaginative things done by SPAL was to offel' reduced xerox copies of 40, sixteen-page frames, exhibited at Colmar in 1974. Many of these covered the double-franking period. Before mounting my collection I decided to review the SPAL literature to get a feeling for what is common and what is rare. -

Nilo-Saharan’

11 Linguistic Features and Typologies in Languages Commonly Referred to as ‘Nilo-Saharan’ Gerrit J. Dimmendaal, Colleen Ahland, Angelika Jakobi, and Constance Kutsch Lojenga 11.1 Introduction The phylum referred to today as Nilo- Saharan (occasionally also Nilosaharan) was established by Greenberg (1963). It consists of a core of language families already argued to be genetically related in his earlier classiication of African languages (Greenberg 1955:110–114), consisting of Eastern Sudanic, Central Sudanic, Kunama, and Berta, and grouped under the name Macrosudanic; this language family was renamed Chari- Nile in his 1963 contribution after a suggestion by the Africanist William Welmers. In his 1963 classiication, Greenberg hypothesized that Nilo- Saharan consists of Chari- Nile and ive other languages or language fam- ilies treated as independent units in his earlier study: Songhay (Songhai), Saharan, Maban, Fur, and Koman (Coman). Bender (1997) also included the Kadu languages in Sudan in his sur- vey of Nilo-Saharan languages; these were classiied as members of the Kordofanian branch of Niger-Kordofanian by Greenberg (1963) under the name Tumtum. Although some progress has been made in our knowledge of the Kadu languages, they remain relatively poorly studied, and there- fore they are not further discussed here, also because actual historical evi- dence for their Nilo- Saharan afiliation is rather weak. Whereas there is a core of language groups now widely assumed to belong to Nilo- Saharan as a phylum or macro- family, the genetic afiliation of families such as Koman and Songhay is also disputed (as for the Kadu languages). For this reason, these latter groups are discussed separately from what is widely considered to form the core of Nilo- Saharan, Central Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

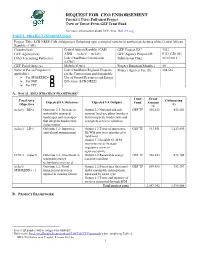

REQUEST for CEO ENDORSEMENT PROJECT TYPE: Full-Sized Project TYPE of TRUST FUND:GEF Trust Fund

REQUEST FOR CEO ENDORSEMENT PROJECT TYPE: Full-sized Project TYPE OF TRUST FUND:GEF Trust Fund For more information about GEF, visit TheGEF.org PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: LCB-NREE CAR child project: Enhancing agro-ecological systems in northern prefectures of the Central African Republic (CAR) Country(ies): Central African Republic (CAR) GEF Project ID:1 9532 GEF Agency(ies): AfDB (select) (select) GEF Agency Project ID: P-Z1-CZ0-001 Other Executing Partner(s): Lake Chad Basin Commission Submission Date: 06/16/2016 (LCBC) GEF Focal Area (s): Multifocal Area Project Duration(Months) 60 Name of Parent Program (if Lake Chad Basin Regional Program Project Agency Fee ($): 204,636 applicable): for the Conservation and Sustainable For SFM/REDD+ Use of Natural Resources and Energy For SGP Efficiency (LCB-NREE) For PPP A. FOCAL AREA STRATEGY FRAMEWORK2 Trust Grant Focal Area Cofinancing Expected FA Outcomes Expected FA Outputs Fund Amount Objectives ($) ($) (select) BD-2 Outcome 2.1: Increase in Output 2.2 National and sub- GEF TF 502,453 855,203 sustainably managed national land-use plans (number) landscapes and seascapes that incorporate biodiversity and that integrate biodiversity ecosystem services valuation conservation (select) LD-1 Outcome 1.2: Improved Output 1.2 Types of innovative GEF TF 913,551 1,113,890 agricultural management SL/WM practices introduced at field level Output 1.3 Suitable SL/WM interventions to increase vegetative cover in agroecosystems CCM-3 (select) Outcome 3.2: Investment in Output 3.2 Renewable energy GEF TF 502,453 672,100 renewable energy capacity installed technologies increased (select) Outcome 1.2: Good Output 1.2 Forest area (hectares) GEF TF 639,485 753,307 SFM/REDD+ - 1 management practices under sustainable management, applied in existing forests separated by forest type Output 1.3 Types and quantity of services generated through SFM Total project costs 2,557,942 3,394,500 B. -

"Evolution of Human Languages": Current State of Affairs

«Evolution of Human Languages»: current state of affairs (03.2014) Contents: I. Currently active members of the project . 2 II. Linguistic experts associated with the project . 4 III. General description of EHL's goals and major lines of research . 6 IV. Up-to-date results / achievements of EHL research . 9 V. A concise list of actual problems and tasks for future resolution. 18 VI. EHL resources and links . 20 2 I. Currently active members of the project. Primary affiliation: Senior researcher, Center for Comparative Studies, Russian State University for the Humanities (Moscow). Web info: http://ivka.rsuh.ru/article.html?id=80197 George Publications: http://rggu.academia.edu/GeorgeStarostin Starostin Research interests: Methodology of historical linguistics; long- vs. short-range linguistic comparison; history and classification of African languages; history of the Chinese language; comparative and historical linguistics of various language families (Indo-European, Altaic, Yeniseian, Dravidian, etc.). Primary affiliation: Visiting researcher, Santa Fe Institute. Formerly, professor of linguistics at the University of Melbourne. Ilia Publications: http://orlabs.oclc.org/identities/lccn-n97-4759 Research interests: Genetic and areal language relationships in Southeast Asia; Peiros history and classification of Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian, Austroasiatic languages; macro- and micro-families of the Americas; methodology of historical linguistics. Primary affiliation: Senior researcher, Institute of Slavic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow / Novosibirsk). Web info / publications list (in Russian): Sergei http://www.inslav.ru/index.php?option- Nikolayev =com_content&view=article&id=358:2010-06-09-18-14-01 Research interests: Comparative Indo-European and Slavic studies; internal and external genetic relations of North Caucasian languages; internal and external genetic relations of North American languages (Na-Dene; Algic; Mosan). -

Discharge of the Congo River Estimated from Satellite Measurements

Discharge of the Congo River Estimated from Satellite Measurements Senior Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Science Degree At The Ohio State University By Lisa Schaller The Ohio State University Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………..….....Page iii List of Figures ………………………………………………………………...……….....Page iv Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….....Page 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………….....Page 2 Study Area ……………………………………………………………..……………….....Page 3 Geology………………………………………………………………………………….....Page 5 Satellite Data……………………………………………....…………………………….....Page 6 SRTM ………………………………………………………...………………….....Page 6 HydroSHEDS ……………………………………………………………….….....Page 7 GRFM ……………………………………………………………………..…….....Page 8 Methods ……………………………………………………………………………..….....Page 9 Elevation ………………………………………………………………….…….....Page 9 Slopes ………………………………………………………………………….....Page 10 Width …………………………………………….…………………………….....Page 12 Manning’s n ……………………………………………………………..…….....Page 14 Depths ……………………………………………………………………...….....Page 14 Discussion ………………………………………………………………….………….....Page 15 References ……………………………….…………………………………………….....Page 18 Figures …………………………………………………………………………...…….....Page 20 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank OSU’s Climate, Water and Carbon program for their generous support of my research project. I would also like to thank NASA’s programs in Terrestrial Hydrology and in Physical Oceanography for support and data. Without Doug Alsdorf and Michael Durand, this project would -

Lexical Evidence for Kordofanian

KORDOFANIAN and NIGER-CONGO: NEW AND REVISED LEXICAL EVIDENCE DRAFT ONLY [N.B. bibliography and sources not fully complete] Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone/Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and Terminology............................................................................................................................ i 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Is there evidence for the unity of Kordofanian?....................................................................................... 3 2.1 Languages falling within Kordofanian.................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Kordofanian Phonology .......................................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Kordofanian noun-class morphology...................................................................................................... 3 3. The lexical evidence for Niger-Congo affiliation...................................................................................... 4 3.1 Previous suggestions ............................................................................................................................... 4 3.2 New and amended proposed cognate sets -

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages Gerrit J. Dimmendaal University of Cologne John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American 8 National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dimmendaal, Gerrit Jan. Historical linguistics and the comparative study of African languages / Gerrit J. Dimmendaal. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. African languages--Grammar, Comparative. 2. Historical linguistics. I. Title. PL8008.D56 2011 496--dc22 2011002759 isbn 978 90 272 1178 1 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 1179 8 (Pb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 8722 9 (Eb) © 2011 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Company • P.O. Box 36224 • 1020 me Amsterdam • The Netherlands John Benjamins North America • P.O. Box 27519 • Philadelphia PA 19118-0519 • USA UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Table of contents Preface ix Figures xiii Maps xv Tables