An Era of Sweeping Change in Diamond and Colored Stone Production and Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finish, Culet Size, and Girdle Thickness: Categories of the GIA Diamond Cut Grading System

Finish, Culet Size, and Girdle Thickness: Categories of the GIA Diamond Cut Grading System This booklet summarizes the relationship of Finish, Culet Size, and Girdle Thickness to the GIA Cut Grading System for round brilliant diamonds. It is intended to help members of the jewelry trade better understand the attributes of diamond appearance, and how those attributes are evaluated within the GIA Cut Grading System. Finish—Polish and Symmetry In the GIA Cut Grading System for standard round brilliant To determine the relationship between finish and overall diamonds, finish (for Polish and Symmetry features) is cut quality, GIA conducted extensive observation testing factored into the final overall cut grade as follows: of numerous diamonds using standardized lighting and viewing conditions. Observations of diamonds with • To qualify for an Excellent cut grade, polish and comparable proportions, but differing in their polish and symmetry must be Very Good or Excellent. symmetry categories, were analyzed to determine the effects of finish on overall cut appearance. In this way, • To qualify for a Very Good cut grade, both polish GIA found that a one grade difference between the other and symmetry must be at least Good. aspects of a diamond’s cut grade and its polish and • To qualify for a Good cut grade, both polish and symmetry assessments did not significantly lower a symmetry must be at least Fair. trained observer’s assessment of face-up appearance, and could not be discerned reliably with the unaided eye— • To qualify for a Fair cut grade, both polish and e.g., polish and/or symmetry descriptions of Very Good symmetry must be at least Fair. -

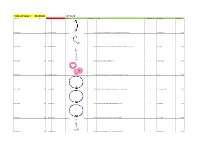

Total Lot Value = $8,189.80 LOT #128 Location Id Lot # Item Id Sku Image Store Price Model Store Quantity Classification Total Value

Total Lot Value = $8,189.80 LOT #128 location_id Lot # item_id sku Image store_price model store_quantity classification Total Value A07-S05-D001 128 182363 TICB-1001 $13.95 16G 5/16" Internally Threaded Implant Grade Titanium Curved Barbell 8 Curved Barbell $111.60 A07-S05-D003 128 186942 NR-1316 $8.95 Purple 2mm Bezel-Set Synthetic Opal Rose Gold-Tone Steel Nose Ring Twist 1 Nose Ring $8.95 A07-S05-D005 128 65492 A208 $11.99 Celtic Swirl Reverse Belly Button Ring 4 Belly Ring Sale $47.96 A07-S05-D006 128 104247 PLG-1345-14 $10.95 9/16" Pink Heart-Shaped Cut Out Flexible Silicone Tunnel Plugs Pair 4 Plugs $43.80 A07-S05-D007 128 65494 D103 $5.95 16G 3/8 - Anodized Rainbow Titanium-Plated Captive Bead Ring 3 Captive Ring , Daith $17.85 A07-S05-D008 128 65496 D103b $5.95 Rainbow Titanium-Plated Captive Bead Ring - 14G 1/2 1 Captive Ring $5.95 A07-S05-D010 128 65499 D103d $4.99 16G 5/8 - Rainbow Anodized Steel Captive Bead Ring 51 Captive Ring $254.49 A07-S05-D011 128 87697 BR-1429 $11.99 Pink CZ Crown & Flower Dangle Belly Button Navel Ring 2 Belly Ring Sale $23.98 A07-S05-D012 128 64066 BR-1496 $11.99 Purple CZ Crown & Flower Dangle Belly Button Navel Ring 4 Belly Ring Sale $47.96 A07-S05-D013 128 65502 D111 $5.99 Spiky -Ball Twister - Body Jewelry 14 Gauge 43 Twister Barbell Sale $257.57 A07-S05-D014 128 104271 PLG-1345-16 $10.95 5/8" - Pink Heart-Shaped Cut Out Flexible Silicone Tunnel Plugs - Pair 2 Plugs $21.90 A07-S05-D015 128 104185 PLG-1345-4 $8.95 6G - Pink Heart-Shaped Cut Out Flexible Silicone Tunnel Plugs - Pair 2 Plugs $17.90 -

The Chemistry of Diamond Rings

THE CHEMISTRY OF DIAMOND RINGS Diamond rings are synonymous with engagements; diamond itself is an form (allotrope) of carbon, but other chemical elements can impact on its appearance. Here we look at ‘the 4 Cs’ and their chemistry links, as well as some of the metallic elements that help to make up the ring itself. DIAMOND CUT DIAMOND CARAT 0.25 Ct 0.50 Ct 0.75 Ct 1.00 Ct 1.50 Ct 2.00 Ct 4.1 mm 5.2 mm 5.8 mm 6.5 mm 7.4 mm 8.2 mm SHALLOW IDEAL DEEP Top: weight in carats; Bottom: approximate diameter in millimetres. Diamonds not shown to scale, but are in proportion to each other. The cut of a diamond affects how well it reflects light. Diamond carat measures mass; one carat is equal to two Too shallow or too deep and the reflection of light is poor, hundred milligrams. Diameters are approximate, as they so the diamond seems to sparkle less. vary depending on the cut of the diamond. DIAMOND COLOUR DIAMOND CLARITY RING COMPOSITION WHITE GOLD Au 75% Pd 10% Ni 10% Zn 5% Rh PLATE D → F G → J K → M N → R S → Z F → IF VVS1/2 VS1/2 SI1/2 I1/2/3 ALMOST FAINT VERY LIGHT LIGHT COLOURLESS FLAWLESS OR VERY VERY VERY STERLING SILVER COLOURLESS YELLOW YELLOW YELLOW SLIGHTLY INTERNALLY SLIGHTLY SLIGHTLY INCLUDED INCLUDED FLAWLESS INCLUDED INCLUDED Ag 92.5% Cu 7.5% Pt TRACE Ge TRACE Zn TRACE POTENTIAL ELEMENTAL IMPURITIES GAINED DURING DIAMOND GROWTH 7 5 1 14 15 28 27 YELLOW GOLD Compositions given are NITROGENN BoronB HYDROGENH Sisilicon PHOSPHORUSP NiNickel Cocobalt TYPE Ia TYPE Ib TYPE IIa TYPE IIb approximate for a typical 0–0.3% N 0–0.05% N 0% N B impurities Au 75% Cu 12.5% Ag 12.5% alloy, and can vary slightly (clusters) (diffuse) Most diamonds have some imperfections. -

Download Course Outline for This Program

Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork NUNAVUT INUIT LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) PROGRAM REPORT 434 Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Status: Approved Action Type: N/A Change Type: N/A Discontinued: No Latest Version: Yes Printed: 03/30/2015 1 Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork Program Details 434 - Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Details Code 434 Title Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term No Specified End Date End Term No Specified End Date Total Credits Institution Nunavut Faculty Inuit Languages and Cultures Department Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) General Information Eligible for RPL No Description The Program in Jewellery and Metalwork will enable students to develop their knowledge and skills of jewellery and metalwork production in a professional studio atmosphere. To this end the program stresses high standards of craftship and creativity, all the time encouraging and exposing students to a wide range of materials, techniques and concepts. This program is designed to allow the individual student to specialize in an area of study of particular interest. There is an emphasis on creative thinking and problem-solving throughout the program.The first year of the program provides an environment for the students to acquire the necessary skills that will enable them to translate their ideas into two and three dimensional jewellery and metalwork. This first year includes courses in: Drawing and Design, Inuit Art and Jewellery History, Lapidary and also Business and Communications. -

The Wittelsbach-Graff and Hope Diamonds: Not Cut from the Same Rough

THE WITTELSBACH-GRAFF AND HOPE DIAMONDS: NOT CUT FROM THE SAME ROUGH Eloïse Gaillou, Wuyi Wang, Jeffrey E. Post, John M. King, James E. Butler, Alan T. Collins, and Thomas M. Moses Two historic blue diamonds, the Hope and the Wittelsbach-Graff, appeared together for the first time at the Smithsonian Institution in 2010. Both diamonds were apparently purchased in India in the 17th century and later belonged to European royalty. In addition to the parallels in their histo- ries, their comparable color and bright, long-lasting orange-red phosphorescence have led to speculation that these two diamonds might have come from the same piece of rough. Although the diamonds are similar spectroscopically, their dislocation patterns observed with the DiamondView differ in scale and texture, and they do not show the same internal strain features. The results indicate that the two diamonds did not originate from the same crystal, though they likely experienced similar geologic histories. he earliest records of the famous Hope and Adornment (Toison d’Or de la Parure de Couleur) in Wittelsbach-Graff diamonds (figure 1) show 1749, but was stolen in 1792 during the French T them in the possession of prominent Revolution. Twenty years later, a 45.52 ct blue dia- European royal families in the mid-17th century. mond appeared for sale in London and eventually They were undoubtedly mined in India, the world’s became part of the collection of Henry Philip Hope. only commercial source of diamonds at that time. Recent computer modeling studies have established The original ancestor of the Hope diamond was that the Hope diamond was cut from the French an approximately 115 ct stone (the Tavernier Blue) Blue, presumably to disguise its identity after the that Jean-Baptiste Tavernier sold to Louis XIV of theft (Attaway, 2005; Farges et al., 2009; Sucher et France in 1668. -

Preliminary Investigation of Purple Garnet from a New Deposit in Mozambique

GIT GEMSTONE UPDATE Preliminary Investigation of Purple Garnet from a New Deposit in Mozambique By GIT-Gem testing laboratory 11 May 2016 Introduction In March 2016, a group of Thai gem dealer led by Mr. Pichit Nilprapaporn paid a visit to the GIT and informed us about a new garnet deposit in Mozambique, that was discovered near the western border with Zimbabwe. They also displayed a large parcel of rough and a few cut stones claimed to be the material found in this new deposit (Figure 1). According to the stone’s owner, these garnet specimens were unearthed from an unconsolidated sediment layer, just a few meters below ground surface. This brief report is our preliminary investigation on the interesting vivid purple garnet from the new deposit in Mozambique. Figure 1: Mr. Pichit Nilprapaporn (center), the stone’s owner, showing a large parcel of purple gar- net roughs claimed to be from a new deposit in Mozambique to the GIT director (left). The Gem and Jewelry Institute of Thailand (Public Organization) 140, 140/1-3, 140/5 ITF-Tower Building. 1st - 4th and 6th Floor,Silom Road, Suriyawong, Bangrak, Bangkok 10500 Thailand Tel: +66 2634 4999 Fax: +66 2634 4970; Web: http://www.git.or.th; E-mail: [email protected] 11 May, 2016 Preliminary Investigation of Purple Garnet from a New Deposit in Mozambique 2 Samples and Testing Procedure The stone’s owners donated some specimens (one 6.10 ct oval-facetted stone and 13 rough samples weighing from 3.83 to 9.43 cts) to the GIT Gem Testing Laboratory for studying. -

HIGHLIGHTS and BREAKTHROUGHS Sapphire, A

1 HIGHLIGHTS AND BREAKTHROUGHS 2 Sapphire, a not so simple gemstone 3 F. LIN SUTHERLAND1* 4 1Geoscience, Australian Museum, 1 William Street, Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia. 5 *E-mail: [email protected] 6 Abstract: Sapphire is a gemstone of considerable reach and is much researched. It still delivers scientific surprises, as exemplified by a 7 recent paper in American Mineralogist that re-interprets the origin of needle-like rutile inclusions that form “silk” in sapphires. 8 Understanding of variations in sapphire genesis continues to expand. Keywords: Sapphire, inclusions, trace elements, genesis 9 Sapphire as a gem variety of corundum has wide use in the gem trade as one of the more historically valuable colored gem stones 10 (CGS) and is mined from a great variety of continental gem deposits across the world. A masterly compendium on this gemstone and its 11 ramifications is recently available (Hughes 2017). As a gem, sapphire ranges through all the colors of corundum, except where 12 sufficient Cr enters its α-alumina crystal structure and causes the red color of the variety ruby. Sapphire, as a key pillar in a wide 13 economic network of gem enhancing treatments, jewelry and other manufacturing enterprises, has elicited numerous scientific and 14 gemological enquiries into its internal nature and natural genesis and subsequent treatments. A further use of sapphire as a synthetic 15 material with a great variety of purposes also has triggered a proliferation of detailed studies on its growth, properties and other element 16 substitutional effects (Dobrovinski et al. 2009). Even with this vast range of studies, this apparently simple gemstone still yields 17 controversies and breakthroughs in understanding its genetic formation. -

Star of the South: a Historic 128 Ct Diamond

STAR OF THE SOUTH: A HISTORIC 128 CT DIAMOND By Christopher P. Smith and George Bosshart The Star of the South is one of the world’s most famous diamonds. Discovered in 1853, it became the first Brazilian diamond to receive international acclaim. This article presents the first complete gemological characterization of this historic 128.48 ct diamond. The clarity grade was deter- mined to be VS2 and the color grade, Fancy Light pinkish brown. Overall, the gemological and spectroscopic characteristics of this nominal type IIa diamond—including graining and strain pat- terns, UV-Vis-NIR and mid- to near-infrared absorption spectra, and Raman photolumines- cence—are consistent with those of other natural type IIa diamonds of similar color. arely do gemological laboratories have the from approximately 1730 to 1870, during which opportunity to perform and publish a full ana- time Brazil was the world’s principal source of dia- Rlytical study of historic diamonds or colored mond. This era ended with the discovery of more stones. However, such was the case recently when significant quantities of diamonds in South Africa. the Gübelin Gem Lab was given the chance to ana- According to Levinson (1998), it has been esti- lyze the Star of the South diamond (figure 1). This mated that prior to the Brazilian finds only about remarkable diamond is not only of historical signifi- 2,000–5,000 carats of diamonds arrived in Europe cance, but it is also of known provenance—cut from annually from the mines of India. In contrast, the a piece of rough found in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazilian finds supplied an estimated 25,000 to Brazil, almost 150 years ago. -

Blue Diamond Prices Are on the Rise

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit http://www.djreprints.com. https://www.barrons.com/articles/blue-diamond-prices-are-on-the-rise-1518037930 Blue Diamond Prices Are on the Rise By Ariel R. Shapiro Feb. 7, 2018 4:12 p.m. ET The fancy color diamond market is on the upswing, according to a report, with blue diamonds seeing the largest gains. Blue diamonds saw a 5.9% increase in value in the fourth quarter of 2017 in a year-over-year comparison, according to data published on Feb. 1 by the Fancy Color Research Foundation (FCRF). Pink and yellow diamond prices decreased slightly in the same period, at 0.8% and 1.8%, respectively. The market overall was up 0.1%. A fancy vivid blue diamond ring (est. $14-18 million) goes on view at Sotheby's on Oct. 13, 2017 in London. ILLUSTRATION: GETTY IMAGES FOR SOTHEBY'S In November 2017, Christie’s sold a 8.67-carat fancy intense blue diamond ring in Geneva, Switzerland for $13.2 million. The reason for this disparity has less to do with demand, than it does with the rarity of the stone, says FCRF Chairman Eden Rachminov. Demand for yellow and pink diamonds is actually higher, but the amount of blue diamonds being mined is decreasing. “Almost nothing is coming out of the ground,” he says. Pink diamonds have seen the highest gains in the last 13 years with an overall appreciation of 361.9%, according to FCRF’s index, which is compiled through survey data provided by manufacturers and brokers. -

THE CUTTING PROPERTIES of KUNZITE by John L

THE CUTTING PROPERTIES OF KUNZITE By John L. Ramsey In the process of cutting l~unzite,a lapidary comes THE PROBLEMS OF PERFECT CLEAVAGE face-to-face with problem properties that sometimes AND RESISTANCE' TO ABRASION remain hidden from the jeweler. By way of ex- amining these problems, we present the example of Kunzite is a variety of spodumene, a lithium alu- a one-kilo kunzite crystal being cut. The cutting minum silicate (see box). Those readers who are problems shown give ample warning to the jeweler familiar with either cutting or mounting stones to take care in working with kunzite and dem- in jewelry are aware of the problems that spodu- onstrate the necessity of cautioning customers to mene, in this case kunzite, invariably poses. For avoid shocking the stone when they wear it in those unfamiliar, it is important to note that kun- jewelry. zite has two distinct cleavages. Perfect cleavage in a stone means that splitting, when it occurs, tends to produce plane surfaces. Cleavage in two directions means that the splitting can occur in The difficulties inherent in faceting lzunzite are a plane along either of two directions in the crys- legendary to the lapidary. Yet the special cutting tal. The property of cleavage, while not desirable problems of this stone also provide an important in a gemstone, does not in and of itself mean trou- perspective for the jeweler. The cutting process ble. For instance, diamond tends to cleave but reveals all of the stone's intrinsic mineralogical splits with such difficulty that diamonds are cut, problems to anyone who works with it, whether mounted, and worn with little trepidation. -

Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana

Report of Investigation 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg 2015 Cover photo by Richard Berg. Sapphires (very pale green and colorless) concentrated by panning. The small red grains are garnets, commonly found with sapphires in western Montana, and the black sand is mainly magnetite. Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology MBMG Report of Investigation 23 2015 i Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 Descriptions of Occurrences ..................................................................................................7 Selected Bibliography of Articles on Montana Sapphires ................................................... 75 General Montana ............................................................................................................75 Yogo ................................................................................................................................ 75 Southwestern Montana Alluvial Deposits........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Rock Creek sapphire district ........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Dry Cottonwood Creek deposit and the Butte area .................................... -

Not for Publication United States Court of Appeals

NOT FOR PUBLICATION FILED DEC 20 2018 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS MOLLY C. DWYER, CLERK FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT U.S. COURT OF APPEALS CYNTHIA CARDARELLI PAINTER, No. 17-55901 individually and on behalf of other members of the general public similarly situated, D.C. No. 2:17-cv-02235-SVW-AJW Plaintiff-Appellant, v. MEMORANDUM* BLUE DIAMOND GROWERS, a California corporation and DOES, 1-100, inclusive, Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Stephen V. Wilson, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted December 3, 2018 Pasadena, California Before: D.W. NELSON and WARDLAW, Circuit Judges, and PRATT,** District Judge. * This disposition is not appropriate for publication and is not precedent except as provided by Ninth Circuit Rule 36-3. ** The Honorable Robert W. Pratt, United States District Judge for the Southern District of Iowa, sitting by designation. Cynthia Painter appeals the district court’s order dismissing her complaint with prejudice on grounds of preemption and failure to state a claim pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). On behalf of a putative class, Painter claims that Blue Diamond Growers (“Blue Diamond”) mislabeled its almond beverages as “almond milk” when they should be labeled “imitation milk” because they substitute for and resemble dairy milk but are nutritionally inferior to it. See 21 C.F.R. § 101.3(e)(1). We have jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1291 and review the district court’s dismissal de novo. Durnford v. MusclePharm Corp., 907 F.3d 595, 601 (9th Cir.