Guidance on the Use of Mood Stabilizers for the Treatment of Bipolar Affective Disorder Version 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Your Depressed Patient Bipolar?

J Am Board Fam Pract: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.271 on 29 June 2005. Downloaded from EVIDENCE-BASED CLINICAL MEDICINE Is Your Depressed Patient Bipolar? Neil S. Kaye, MD, DFAPA Accurate diagnosis of mood disorders is critical for treatment to be effective. Distinguishing between major depression and bipolar disorders, especially the depressed phase of a bipolar disorder, is essen- tial, because they differ substantially in their genetics, clinical course, outcomes, prognosis, and treat- ment. In current practice, bipolar disorders, especially bipolar II disorder, are underdiagnosed. Misdi- agnosing bipolar disorders deprives patients of timely and potentially lifesaving treatment, particularly considering the development of newer and possibly more effective medications for both depressive fea- tures and the maintenance treatment (prevention of recurrence/relapse). This article focuses specifi- cally on how to recognize the identifying features suggestive of a bipolar disorder in patients who present with depressive symptoms or who have previously been diagnosed with major depression or dysthymia. This task is not especially time-consuming, and the interested primary care or family physi- cian can easily perform this assessment. Tools to assist the physician in daily practice with the evalua- tion and recognition of bipolar disorders and bipolar depression are presented and discussed. (J Am Board Fam Pract 2005;18:271–81.) Studies have demonstrated that a large proportion orders than in major depression, and the psychiat- of patients in primary care settings have both med- ric treatments of the 2 disorders are distinctly dif- ical and psychiatric diagnoses and require dual ferent.3–5 Whereas antidepressants are the treatment.1 It is thus the responsibility of the pri- treatment of choice for major depression, current mary care physician, in many instances, to correctly guidelines recommend that antidepressants not be diagnose mental illnesses and to treat or make ap- used in the absence of mood stabilizers in patients propriate referrals. -

Types of Bipolar Disorder Toms Are Evident

MOOD DISORDERS ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH COLUmbIA T Y P E S O F b i p o l a r d i s o r d e r Bipolar disorder is a class of mood disorders that is marked by dramatic changes in mood, energy and behaviour. The key characteristic is that people with bipolar disorder alternate be- tween episodes of mania (extreme elevated mood) and depression (extreme sadness). These episodes can last from hours to months. The mood distur- bances are severe enough to cause marked impairment in the person’s func- tioning. The experience of mania is not pleasant and can be very frightening to The Diagnotistic Statisti- the person. It can lead to impulsive behaviour that has serious consequences cal Manual (DSM- IV-TR) is a for the person and their family. A depressive episode makes it difficult or -im manual used by doctors to possible for a person to function in their daily life. determine the specific type of bipolar disorder. People with bipolar disorder vary in how often they experience an episode of either mania or depression. Mood changes with bipolar disorder typically occur gradually. For some individuals there may be periods of wellness between the different mood episodes. Some people may also experience multiple episodes within a 12 month period, a week, or even a single day (referred to as “rapid cycling”). The severity of the mood can also range from mild to severe. Establishing the particular type of bipolar disorder can greatly aid in determin- ing the best type of treatment to manage the symptoms. -

Homicide and Associated Steroid Acute Psychosis: a Case Report

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Medicine Volume 2011, Article ID 564521, 4 pages doi:10.1155/2011/564521 Case Report Homicide and Associated Steroid Acute Psychosis: A Case Report G. Airagnes,1, 2 C. Rouge-Maillart,1, 3 J.-B. Garre,2, 3 and B. Gohier2 1 Service de M´edecine L´egale, CHU d’Angers, 49933 Angers Cedex 09, France 2 D´epartement de Psychiatrie et de Psychologie m´edicale, CHU d’Angers, 49933 Angers Cedex 09, France 3 IFR 132, Universit´e d’Angers, 49035 Angers, France Correspondence should be addressed to G. Airagnes, [email protected] Received 22 June 2011; Revised 26 August 2011; Accepted 26 September 2011 Academic Editor: Massimo Gallerani Copyright © 2011 G. Airagnes et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. We report the case of an old man treated with methylprednisolone for chronic lymphoid leukemia. After two months of treatment, he declared an acute steroid psychosis and beat his wife to death. Steroids were stopped and the psychotic symptoms subsided, but his condition declined very quickly. The clinical course was complicated by a major depressive disorder with suicidal ideas, due to the steroid stoppage, the leukemia progressed, and by a sudden onset of a fatal pulmonary embolism. This clinical case highlights the importance of early detection of steroid psychosis and proposes, should treatment not be stopped, a strategy of dose reduction combined with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic treatment. -

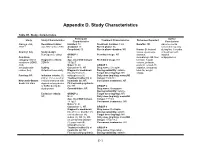

Appendix D. Study Characteristics

Appendix D. Study Characteristics Table D1. Study characteristics Participant Author Study Study Characteristics Treatment Characteristics Outcomes Reported Characteristics Conclusions Alacqua et al., Recruitment dates: Enrolled: 73 Treatment duration: 3 mo Benefits: NR Adverse events 2008 96 Jan 2002 to Dec 2003 Analyzed: 73 Run-in phase: No occurred frequently Completed: 50 Run-in phase duration: NR Harms: Behavioral during first 3 months Country: Italy Study design: issues, dyskinesia, of treatment with Retrospective cohort GROUP 1 Permitted drugs: NR dystonia, atypical Condition N: 2 dermatologic AE, liver antipsychotics. category: Mixed Diagnostic criteria: Age, mean±SD (range): Prohibited drugs: NR function, hepatic conditions (ADHD, DSM-IV 15.5±0.7 volume, prolactin, ASD, Males %: 50 GROUP 1 prolactin-related AE, schizophrenia- Setting: Caucasian %: NR Drug name: Clozapine sedation, sleepness, related, tics) Outpatient/community Diagnostic breakdown Dosing variability: variable total AE, weight (n): psychosis (1), Target dose (mg/day): NR change Funding: NR Inclusion criteria: (1) schizophrenia (1) Daily dose (mg/day), mean±SD ≤18 yr, (2) received an Treatment naïve (n): all (range): 150±70.1 Newcastle-Ottawa incident treatment with Inpatients (n): NR Concurrent treatments: NR Scale: 6/8 stars atypical antipsychotics First episode psychosis or SSRIs during the (n): NR GROUP 2 study period Comorbidities: NR Drug name: Olanzapine Dosing variability: variable Exclusion criteria: GROUP 2 Target dose (mg/day): NR NR N: 24 Daily dose -

Mechanism of Action of Antidepressants and Mood Stabilizers

79 MECHANISM OF ACTION OF ANTIDEPRESSANTS AND MOOD STABILIZERS ROBERT H. LENOX ALAN FRAZER Bipolar disorder (BPD), the province of mood stabilizers, the more recent understanding that antidepressants share has long been considered a recurrent disorder. For more this property in UPD have focused research on long-term than 50 years, lithium, the prototypal mood stabilizer, has events, such as alterations in gene expression and neuroplas- been known to be effective not only in acute mania but ticity, that may play a significant role in stabilizing the clini- also in the prophylaxis of recurrent episodes of mania and cal course of an illness. In our view, behavioral improvement depression. By contrast, the preponderance of past research and stabilization stem from the acute pharmacologic effects in depression has focused on the major depressive episode of antidepressants and mood stabilizers; thus, both the acute and its acute treatment. It is only relatively recently that and longer-term pharmacologic effects of both classes of investigators have begun to address the recurrent nature of drugs are emphasized in this chapter. unipolar disorder (UPD) and the prophylactic use of long- term antidepressant treatment. Thus, it is timely that we address in a single chapter the most promising research rele- vant to the pharmacodynamics of both mood stabilizers and MOOD STABILIZERS antidepressants. As we have outlined in Fig. 79.1, it is possible to charac- The term mood stabilizer within the clinical setting is com- terize both the course and treatment of bipolar and unipolar monly used to refer to a class of drugs that treat BPD. -

Page 1 of 85 Reference ID: 3091122

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION As an adjunct to 2-5 mg 5-10 mg 15 mg These highlights do not include all the information needed to use ABILIFY antidepressants for the /day /day /day safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for ABILIFY. treatment of major ® ABILIFY (aripiprazole) Tablets depressive disorder – adults ® ABILIFY DISCMELT (aripiprazole) Orally Disintegrating Tablets (2.3) ® Irritability associated with 2 mg/day 5-10 mg/day 15 mg/day ABILIFY (aripiprazole) Oral Solution ® autistic disorder – pediatric ABILIFY (aripiprazole) Injection FOR INTRAMUSCULAR USE ONLY patients (2.4) Initial U.S. Approval: 2002 Agitation associated with 9.75 mg /1.3 30 mg/day schizophrenia or bipolar mL injected injected WARNINGS: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY mania – adults (2.5) IM IM PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS and • Oral formulations: Administer once daily without regard to meals (2) SUICIDALITY AND ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUGS • IM injection: Wait at least 2 hours between doses. Maximum daily dose See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. 30 mg (2.5) • Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with ----------------------DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS--------------------- antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. ABILIFY is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related • Tablets: 2 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, 20 mg, and 30 mg (3) psychosis. (5.1) • Orally Disintegrating Tablets: 10 mg and 15 mg (3) • Oral Solution: 1 mg/mL (3) • Children, adolescents, and young adults taking antidepressants for • Injection: 9.75 mg/1.3 mL single-dose vial (3) major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders are at increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior. -

Active Moiety Name FDA Established Pharmacologic Class (EPC) Text

FDA Established Pharmacologic Class (EPC) Text Phrase PLR regulations require that the following statement is included in the Highlights Indications and Usage heading if a drug is a member of an EPC [see 21 CFR 201.57(a)(6)]: “(Drug) is a (FDA EPC Text Phrase) indicated for [indication(s)].” For Active Moiety Name each listed active moiety, the associated FDA EPC text phrase is included in this document. For more information about how FDA determines the EPC Text Phrase, see the 2009 "Determining EPC for Use in the Highlights" guidance and 2013 "Determining EPC for Use in the Highlights" MAPP 7400.13. .alpha. -

Differentiating Schizoaffective and Bipolar Disorder: a Dimensional Approach

ECNP Berlin 2014 Differentiating schizoaffective and bipolar disorder: a dimensional approach Heinz Grunze Newcastle University, Institute of Neuroscience, Academic Psychiatry, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK http://www.ncl.ac.uk/ion/staff/profile/heinz.grunze http://www.ntw.nhs.uk/sd.php?l=2&d=9&sm=15&id=237 Disclosures o I have received grants/research support, consulting fees and honoraria within the last three years from BMS, Desitin, Eli Lilly, Gedeon Richter, Hoffmann-La Roche,Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Servier o Research grants: NHS National Institute for Health Research/Medical Research Council UK o Neither I nor any member of my family have shares in any pharmaceutical company or could benefit financially from increases or decreases in the sales of any psychotropic medication. During this presentation, some medication may be mentioned which are off-label and not or not yet licensed for the specified indication!! The content of the talk represents solely the opinion of the speaker, not of the sponsor. SCZ and BD means impairment at multiple levels- and we assume SAD, too Machado-Vieira et al, 2013 The polymorphic course of Schizoaffective Disorder Schizophrenic Depressive Manic syndrome syndrome syndrome Marneros et al. 1995. Dimensional view of Schizoaffective Disorder (SAD) vs Bipolar Disorder (BD) Genes Brain morphology and Function Symptomatology Outcome Dimension SAD AND GENES Bipolar and schizophrenia are not so different….. 100% Non-shared environmental 90% effects 80% 70% Shared environmental 60% effects 50% 40% 30% Unique genetic effects 20% 10% 0% Shared genetic effects Schizophrenia Bipolar Disorder Variance accounted for by genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental effects for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. -

Biological Boundaries Between Bipolar I Disorder, Schizoaffective Disorder, and Schizophrenia Victoria E Cosgrove1,2 and Trisha Suppes1,2*

Cosgrove and Suppes BMC Medicine 2013, 11:127 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/127 $VSSFOU$POUSPWFSTJFTJO1TZDIJBUSZ DEBATE Open Access Informing DSM-5: biological boundaries between bipolar I disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia Victoria E Cosgrove1,2 and Trisha Suppes1,2* Abstract Background: The fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) opted to retain existing diagnostic boundaries between bipolar I disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. The debate preceding this decision focused on understanding the biologic basis of these major mental illnesses. Evidence from genetics, neuroscience, and pharmacotherapeutics informed the DSM-5 development process. The following discussion will emphasize some of the key factors at the forefront of the debate. Discussion: Family studies suggest a clear genetic link between bipolar I disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. However, large-scale genome-wide association studies have not been successful in identifying susceptibility genes that make substantial etiological contributions. Boundaries between psychotic disorders are not further clarified by looking at brain morphology. The fact that symptoms of bipolar I disorder, but not schizophrenia, are often responsive to medications such as lithium and other anticonvulsants must be interpreted within a larger framework of biological research. Summary: For DSM-5, existing nosological boundaries between bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia were retained and schizoaffective disorder preserved as an independent diagnosis since the biological data are not yet compelling enough to justify a move to a more neurodevelopmentally continuous model of psychosis. Keywords: Bipolar disorder, Hallucinations, Delusions, Schizoaffective disorder, Schizophrenia, DSM- 5, Genes, Psychiatric medication, Brain function Background distinguishing psychotic disorders [2] and, more broadly, Development of the fifth version of the Diagnostic and all psychiatric disorders [3-5]. -

Mood Stabilizers

Mood Stabilizers Anticonvulsants Depakene/Stavzor (valproic acid) and Depakote/Depakote ER (divalproex sodium) Equetro, Tegretol, and Tegretol-XR (carbamazepine) Lamictal (lamotrigine) Lyrica (pregabalin) Neurontin (gabapentin) Topamax (topiramate) Trileptal (oxcarbazepine) Lithium Carbonate and Lithium Citrate Lithium carbonate Lithium Citrate Lithobid Second-Generation Antipsychotics Abilify (aripiprazole) Clozaril (clozapine) Geodon (ziprasidone) Invega (paliperidone) Risperdal, Risperdal M-Tab, and Risperdal Consta (risperidone) Seroquel (quetiapine) Zyprexa and Zyprexa Zydis (olanzapine) Simply defined, mood stabilizers are medicines used in treating mood disorders such as bipolar disorder and depression. Bipolar disorder is characterized by mood swings in which the individual cycles between mania and depression. The symptoms fluctuate from euphoria and limitless energy in the manic phase to the depths of depression with little energy, guilt, sadness, decreased concentration, lack of appetite, and sleep distur- bance. Because of the wide range of symptoms, from mania to depression, bipolar disorder is often called manic depression. Mood stabilizers are used to treat acute mania, hypomania (a mild form of mania), mixed episodes (when mania and depression coexist in an episode), and depression. Following the acute episode, mood stabilizers Page 2 of 3 MOOD STABILIZERS are used in maintenance therapy to prevent the cyclical relapse of abnormal mood elevations and depressions. The goals of maintenance treatment with a mood stabilizer are to 1) reduce residual symptoms, 2) prevent manic or depressive relapse, 3) reduce the frequency of cycling into the next manic or depressive episode, 4) improve functioning, and 5) reduce the risk of suicide. Lithium Lithium was one of the first mood stabilizers used in the treatment of bipolar disorder. -

A History of the Pharmacological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review A History of the Pharmacological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder Francisco López-Muñoz 1,2,3,4,* ID , Winston W. Shen 5, Pilar D’Ocon 6, Alejandro Romero 7 ID and Cecilio Álamo 8 1 Faculty of Health Sciences, University Camilo José Cela, C/Castillo de Alarcón 49, 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 2 Neuropsychopharmacology Unit, Hospital 12 de Octubre Research Institute (i+12), Avda. Córdoba, s/n, 28041 Madrid, Spain 3 Portucalense Institute of Neuropsychology and Cognitive and Behavioural Neurosciences (INPP), Portucalense University, R. Dr. António Bernardino de Almeida 541, 4200-072 Porto, Portugal 4 Thematic Network for Cooperative Health Research (RETICS), Addictive Disorders Network, Health Institute Carlos III, MICINN and FEDER, 28029 Madrid, Spain 5 Departments of Psychiatry, Wan Fang Medical Center and School of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, 111 Hsin Long Road Section 3, Taipei 116, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Valencia, Avda. Vicente Andrés, s/n, 46100 Burjassot, Valencia, Spain; [email protected] 7 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Complutense University, Avda. Puerta de Hierro, s/n, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 8 Department of Biomedical Sciences (Pharmacology Area), Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Alcalá, Crta. de Madrid-Barcelona, Km. 33,600, 28871 Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: fl[email protected] or [email protected] Received: 4 June 2018; Accepted: 13 July 2018; Published: 23 July 2018 Abstract: In this paper, the authors review the history of the pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder, from the first nonspecific sedative agents introduced in the 19th and early 20th century, such as solanaceae alkaloids, bromides and barbiturates, to John Cade’s experiments with lithium and the beginning of the so-called “Psychopharmacological Revolution” in the 1950s. -

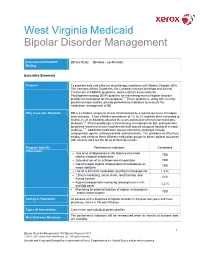

West Virginia Medicaid

West Virginia Medicaid Bipolar Disorder Management Educational RetroDUR Initial Study Follow – up /Restudy Mailing Executive Summary Purpose: To promote safe and effective drug therapy in patients with Bipolar Disorder (BD). The Veterans Affairs Guidelines, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines, and the British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) guideline for the management of bipolar disorder provide the foundation for this proposal.1-3 These guidelines, along with recently published major studies, provide performance indicators to evaluate the medication management of BD. Why Issue was Selected: BD is a complex, long-term illness characterized by a repeating course of relapse and remission. It has a lifetime prevalence of 1% to 2% and has been estimated to lead to 2% of all disability-adjusted life-years associated with non-communicable diseases.4,5 Pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment for BD, and treatment guidelines recommend such regimens be built around adequate dosing of a mood stabilizer.1-3 Additional medication classes commonly employed include antipsychotic agents, antidepressants, and stimulants. The principles to effectively employ and combine these different medication groups to obtain optimal outcomes with minimal risks are the focus of this intervention. Program Specific Performance Indicators Candidates Information: Use of an antidepressant in the absence of a mood TBD stabilizer/atypical antipsychotic Extended use of an antidepressant medication TBD Use of multiple atypical antipsychotics simultaneously as TBD mood stabilizers Use of a stimulant medication resulting in increased risk 1,416 Lithium monitoring: serum levels, renal function, and 660 thyroid function Atypical antipsychotic monitoring: blood glucose levels 3,675 and lipid panel Monitoring for potential toxicities of valproic acid products TBD and/or carbamazepine Setting & Population: All patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in the past two years and have pharmacy claims in the past 90 days.