Björk Reaches Beyond the Binaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mrs. Chase Among Highest-Paid Prep School Heads; It’S About the Individual’S Safety.” 1968

VISIT US ON THE WEB AT www.phillipian.net Volume CXXVIII, Number 24 Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts January 6, 2006 SMOYERʼS $1M INTERNET SAFETY DONATION TO FIX CONCERNS PROMPT ATHLETIC FIELDS E-MAIL WARNING By EMMA WOOD By STEVE BLACKMAN The Andover Athletic and ALEXA REID Department received a generous In light of recent events, Phillips “Christmas present” of $1 million Academy issued a warning to parents from Stanley Smoyer. and students about the danger of Mr. Smoyer requested that using popular networking websites his donation go directly towards like MySpace.com. renovating the drainage system In an e-mail message to parents of the Boys Varsity Soccer fi eld, and faculty sent on December 12, which fl oods often. Dean of Students and Residential “For years, now, the water Life Marlys Edwards clarifi ed school problems have interfered with policy on non-academic computer practices and forced us to cancel use, warning students about the games. The varsity teams deserve dangers inherent in posting personal to have a fi eld they can be proud information on public webpages. of, so we couldn’t be more pleased She wrote, “The safety concerns about this extraordinary gift,” said arising from use of these Internet sites Athletic Director Martha Fenton, are numerous, and they include the according to Director of Public real fear that young people are making Information Steve Porter. themselves vulnerable to predators.” Instructor in Math and Boys’ “[Sites like MySpace] are not Varsity Soccer Coach Bill Scott a bad thing, not at all, but there said to Mr. Porter, “It is our goal is incredible potential for [their] and dream to create the best natural misuse,” said Ms. -

ROSITA MISSONI MARCH 2015 MARCH 116 ISSUE SPRING FASHION SPRING $15 USD 7 2527401533 7 10 03 > > IDEAS in DESIGN Ideas in Design in Ideas

ISSUE 116 SPRING FASHION $15 USD 10> MARCH 2015 03> 7 2527401533 7 ROSITA MISSONI ROSITA IDEAS IN DESIGN Ideas in Design in Ideas STUDIO VISIT My parents are from Ghana in West Africa. Getting to the States was Virgil Abloh an achievement, so my dad wanted me to be an engineer. But I was much more into hip-hop and street culture. At the end of that engi- The multidisciplinary talent and Kanye West creative director speaks neering degree, I took an art-history class. I learned about the Italian with us about hip-hop, Modernism, Martha Stewart, and the Internet Renaissance and started thinking about creativity as a profession. I got from his Milan design studio. a master’s in architecture and was particularly influenced by Modernism and the International Style, but I applied my skill set to other projects. INTERVIEW BY SHIRINE SAAD I was more drawn to cultural projects and graphic design because I found that the architectural process took too long and involved too many PHOTOS BY DELFINO SISTO LEGNANI people. Rather than the design of buildings, I found myself interested in what happens inside of them—in culture. You’re wearing a Sterling Ruby for Raf Simons shirt. What happens when art and fashion come together? Then you started working with Kanye West as his creative director. There’s a synergy that happens when you cross-pollinate. When you use We’re both from Chicago, so we naturally started working together. an artist’s work in a deeper conceptual context, something greater than It takes doers to push the culture forward, so I resonate with anyone fashion or art comes out. -

Download Futuro Anteriore

Numero XVII Estate 2017 futuro anteriore Sommario L'Editorial L’Editorial 3 InSistenze 4 Gusci vuoti alla dervia di Simone Scaloni 5 Nella sottrazione utile... di Anna Laura Longo 9 SETTEMBRE 2017 - N.17- ANNO 5 La cristallomanzia delle vite interrotte di Gioele Marchis 13 L’attimo al fulmicotone di Lucio Costantini 17 www.rivistadiwali.it InVerso 21 «No, non è detto che il passato sia già accaduto, così alla perfezione piattamente presente del digitale, che an- Gianluigi Miani 22 come non è detto che il futuro non lo sia ancora. È cer- nulla ogni profondità dimensionale. O come le visioni vo- Valentina Ciurleo 23 to questo il modo in cui spontaneamente pensiamo il lutamente caricaturali del futuro nella fantascienza, che Direttore Editoriale tempo, ma...Lo spazio di questo ma raccoglie le infinite sappiamo non si produrranno mai come le immaginiamo, Roberto Marzano 24 Maria Carla Trapani possibilità della rappresentazione artistica del futuro an- ma che hanno proprio nel loro essere improbabili la forza Martina Millefiorini 26 teriore, questo tempo strano che già sui banchi di scuola di una protesta, di una resistenza. A volte l’anticato e il Direttore Responsabile Dona Amati 28 ci appariva misterioso. Ma è tutto lì il senso del tempo: futuristico si fondono in una sola immagine doppiamente Flavio Scaloni nella possibilità di pensare adesso qualcosa che oggi o anacronistica, come nello Steampunk, in cui le due dire- Focus Haiku 30 domani sarà passata… zioni convergono in una sola immagine, in un solo suo- Redazione InStante 35 Sarà passata, eccolo un esempio del nostro tempo, no, in una sola parola di resistenza. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

One of a Kind, Unique Artist's Books Heide

ONE OF A KIND ONE OF A KIND Unique Artist’s Books curated by Heide Hatry Pierre Menard Gallery Cambridge, MA 2011 ConTenTS © 2011, Pierre Menard Gallery Foreword 10 Arrow Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 by John Wronoski 6 Paul* M. Kaestner 74 617 868 20033 / www.pierremenardgallery.com Kahn & Selesnick 78 Editing: Heide Hatry Curator’s Statement Ulrich Klieber 66 Design: Heide Hatry, Joanna Seitz by Heide Hatry 7 Bill Knott 82 All images © the artist Bodo Korsig 84 Foreword © 2011 John Wronoski The Artist’s Book: Rich Kostelanetz 88 Curator’s Statement © 2011 Heide Hatry A Matter of Self-Reflection Christina Kruse 90 The Artist’s Book: A Matter of Self-Reflection © 2011 Thyrza Nichols Goodeve by Thyrza Nichols Goodeve 8 Andrea Lange 92 All rights reserved Nick Lawrence 94 No part of this catalogue Jean-Jacques Lebel 96 may be reproduced in any form Roberta Allen 18 Gregg LeFevre 98 by electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or information storage retrieval Tatjana Bergelt 20 Annette Lemieux 100 without permission in writing from the publisher Elena Berriolo 24 Stephen Lipman 102 Star Black 26 Larry Miller 104 Christine Bofinger 28 Kate Millett 108 Curator’s Acknowledgements Dianne Bowen 30 Roberta Paul 110 My deepest gratitude belongs to Pierre Menard Gallery, the most generous gallery I’ve ever worked with Ian Boyden 32 Jim Peters 112 Dove Bradshaw 36 Raquel Rabinovich 116 I want to acknowledge the writers who have contributed text for the artist’s books Eli Brown 38 Aviva Rahmani 118 Jorge Accame, Walter Abish, Samuel Beckett, Paul Celan, Max Frisch, Sam Hamill, Friedrich Hoelderin, John Keats, Robert Kelly Inge Bruggeman 40 Osmo Rauhala 120 Andreas Koziol, Stéphane Mallarmé, Herbert Niemann, Johann P. -

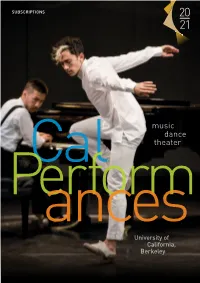

2020-21-Brochure.Pdf

SUBSCRIPTIONS 20 21 music dance Ca l theater Performances University of California, Berkeley Letter from the Director Universities. They exist to foster a commitment to knowledge in its myriad facets. To pursue that knowledge and extend its boundaries. To organize, teach, and disseminate it throughout the wider community. At Cal Performances, we’re proud of our place at the heart of one of the world’s finest public universities. Each season, we strive to honor the same spirit of curiosity that fuels the work of this remarkable center of learning—of its teachers, researchers, and students. That’s why I’m happy to present the details of our 2020/21 Season, an endlessly diverse collection of performances rivaling any program, on any stage, on the planet. Here you’ll find legendary artists and companies like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the Mark Morris Dance Group, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo. And you’ll discover a wide range of performers you might not yet know you can’t live without—extraordinary, less-familiar talent just now emerging on the international scene. This season, we are especially proud to introduce our new Illuminations series, which aims to harness the power of the arts to address the pressing issues of our time and amplify them by shining a light on developments taking place elsewhere on the Berkeley campus. Through the themes of Music and the Mind and Fact or Fiction (please see the following pages for details), we’ll examine current groundbreaking work in the university’s classrooms and laboratories. -

Contemporary Christian Music and Oklahoma

- HOL Y ROCK 'N' ROLLERS: CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC AND OKLAHOMA COLLEGE STUDENTS By BOBBI KAY HOOPER Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1993 Submitted to the Faculty of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August, 2003 HOLY ROCK 'N' ROLLERS: CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC AND OKLAHOMA COLLEGE STUDENTS Thesis Approved: ------'--~~D...e~--e----- 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere appreciation goes out to my adviser. Dr. Jami A. Fullerton. for her insight, support and direction. It was a pleasure and privilege to work with her. My thanks go out to my committee members, Dr. Stan Kerterer and Dr. Tom Weir. ""hose knowledge and guidance helped make this publication possible. I want to thank my friend Matt Hamilton who generously gave of his time 10 act as the moderator for all fOUf of the focus groups and worked with me in analyzing the data. ] also want to thank the participants of this investigation - the Christian college students who so willingly shared their beliefs and opinions. They made research fun r My friends Bret and Gina r.uallen musl nlso be recognii'_cd for introducing me !(l tbe depth and vitality ofChrislian music. Finally. l must also give thanks to my parents. Bohby and Helen Hoopc,;r. whose faith ,md encouragement enabled me to see the possibilities and potential in sitting down. 111 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION Overview ofThesis Research Problem 3 Justification Definition ofTerms 4 [I. LITERATURE REVIEW 5 Theoretical Framework 6 Uses and Gratifications 6 Media Dependency 7 Tuning In: Popular Music Uses and Gratifications 8 Bad Music, Bad Behavior: Effects of Rock Music 11 The Word is Out: Religious Broadcasting 14 Taking Music "Higher": ('eM 17 Uses & Gratifications applied to CCM 22 111. -

Gender Performance in Photography

PHOTOGRAPHY (A CI (A CI GENDER PERFORMANCE IN PHOTOGRAPHY (A a C/VFV4& (A a )^/VM)6e GENDER PERFORMANCE IN PHOTOGRAPHY JENNIFER BLESSING JUDITH HALBERSTAM LYLE ASHTON HARRIS NANCY SPECTOR CAROLE-ANNE TYLER SARAH WILSON GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: front cover: Gender Performance in Photography Claude Cahun Organized by Jennifer Blessing Self- Portrait, ca. 1928 Gelatin-silver print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 11 'X. x 9>s inches (30 x 23.8 cm) January 17—April 27, 1997 Musee des Beaux Arts de Nantes This exhibition is supported in part by back cover: the National Endowment tor the Arts Nan Goldin Jimmy Paulettc and Tabboo! in the bathroom, NYC, 1991 €)1997 The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Cibachrome print, New York. All rights reserved. 30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) Courtesy of the artist and ISBN 0-8109-6901-7 (hardcover) Matthew Marks Gallery, New York ISBN 0-89207-185-0 (softcover) Guggenheim Museum Publications 1071 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10128 Hardcover edition distributed by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 100 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10011 Designed by Bethany Johns Design, New York Printed in Italy by Sfera Contents JENNIFER BLESSING xyVwMie is a c/\rose is a z/vxose Gender Performance in Photography JENNIFER BLESSING CAROLE-ANNE TYLER 134 id'emt nut files - KyMxUcuo&wuieS SARAH WILSON 156 c/erfoymuiq me c/jodt/ im me J970s NANCY SPECTOR 176 ^ne S$r/ of ~&e#idew Bathrooms, Butches, and the Aesthetics of Female Masculinity JUDITH HALBERSTAM 190 f//a« waclna LYLE ASHTON HARRIS 204 Stfrtists ' iyjtoqra/inies TRACEY BASHKOFF, SUSAN CROSS, VIVIEN GREENE, AND J. -

Kunstmuseum Basel, Museum Für Gegenwartskunst Dundee Contemporary Arts

Kunstmuseum Basel, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Dundee Contemporary Arts LOOK BEHIND US, A BLUE SKY Johanna Billing Support for the exhibition in Basel and its accompanying publication has been provided by the “Fonds für künstlerische Aktivitäten im Museum für Gegenwartskunst der Emanuel Hoffmann-Stiftung und der Christoph Merian Stiftung” Die Ausstellung in Basel und die Publikation wurden unterstützt vom »Fonds für künstlerische Aktivitäten im Museum für Gegenwartskunst der Emanuel Hoffmann-Stiftung und der Christoph Merian Stiftung« Expanded Footnotes CONTENTS INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Projects for Revolution Radio Days; Tour Diary Perfect Pop Pleasures Lightning Never Strikes Here 9 Rob Tufnell Johanna Billing, Helena Jacob Wren Anymore… 92 Holmberg, Annie 178 Karl Holmqvist Fletcher, Tanja Elstgeest, Waiting for Billing and Frédérique Bergholtz Pass the Glue Making †ings Happen 12 Making †ings Happen Maria Lind 126 Volker Zander Polly Staple Polly Staple 103 180 You Make Me Digress More Films about Songs, 40 More Films about Songs, Some Notes on Billing, Åbäke †e Lights Go out, Cities & Circles Cities & Circles Stein, and Repetition 150 the Moon Wanes A Conversation between Ein Gespräch zwischen Malin Ståhl Anne Tallentire Johanna Billing & Helena Selder Johanna Billing & Helena Selder 108 More Texts about Songs 185 & Buildings Forever Changes 70 Forever Changes Getting †ere Magnus Haglund A Possible Trilogy A Conversation between Ein Gespräch zwischen Chen Tamir 155 Jelena Vesie Johanna Billing & Philipp Kaiser Johanna Billing & Philipp -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Scanned Image

Compulsion are on our to promote their new Iohri and Sandra welcome you to album The Future ls Medium, out June 17th. Catch them in Leicester (The Charlotte, 20th) or W firstofall: Stoke (The Stage July 3rd). Done Lying Down return from a six week tour of . Nottingham Music. Industry. Week is a four day Europe with Killdozer and Chumbawamba with a event for budding musicians, promoters, sound re-recorded and remixed version on 7" and cd of THE mixers and DJs. Organised by Carlos Thrale of Can’t Be Too Certain from their Kontrapunkt _ u r I S Arnold & Carlton College, one of the few album on Immaterial Records. The cd format OLDEN FLEECE To colleges in the UK to award a BTEC in popular also features three exclusive John Peel session music, in conjunction with Confetti School Of tracks. A UK tour brings them to Leicester (The 105 Mansfield Road Nottingham ’ Recording Technology, Carlsboro Soundaalso Charlotte, July 3rd) and Derby (The Garrick, Traditional Cask Ales involved are the Warehouse Studios and East 4th). ’** Guest Beers "“* msterdam Midlands Arts. The four day event begins on Ambient Prog Rockers The Enid return with a Monday 22nd July comprising seminars and "‘.‘:-5-@5953‘:-5: ' string of summer dates prior to the release of Frankfurt £69 tin workshops led by professionals from all areas of their singles compilation Anarchy On 45. I I n I I - a u u ¢ u I I a n | n - o - | q | I q n I - Q - - - - I I I | ¢ | | n - - - , . , . the music industry, and evening gigs. -

Recordings by Artist

Recordings by Artist Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 10,000 Maniacs MTV Unplugged CD 1993 3Ds The Venus Trail CD 1993 Hellzapoppin CD 1992 808 State 808 Utd. State 90 CD 1989 Adamson, Barry Soul Murder CD 1997 Oedipus Schmoedipus CD 1996 Moss Side Story CD 1988 Afghan Whigs 1965 CD 1998 Honky's Ladder CD 1996 Black Love CD 1996 What Jail Is Like CD 1994 Gentlemen CD 1993 Congregation CD 1992 Air Talkie Walkie CD 2004 Amos, Tori From The Choirgirl Hotel CD 1998 Little Earthquakes CD 1991 Apoptygma Berzerk Harmonizer CD 2002 Welcome To Earth CD 2000 7 CD 1998 Armstrong, Louis Greatest Hits CD 1996 Ash Tuesday, January 23, 2007 Page 1 of 40 Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 1977 CD 1996 Assemblage 23 Failure CD 2001 Atari Teenage Riot 60 Second Wipe Out CD 1999 Burn, Berlin, Burn! CD 1997 Delete Yourself CD 1995 Ataris, The So Long, Astoria CD 2003 Atomsplit Atonsplit CD 2004 Autolux Future Perfect CD 2004 Avalanches, The Since I left You CD 2001 Babylon Zoo Spaceman CD 1996 Badu, Erykah Mama's Gun CD 2000 Baduizm CD 1997 Bailterspace Solar 3 CD 1998 Capsul CD 1997 Splat CD 1995 Vortura CD 1994 Robot World CD 1993 Bangles, The Greatest Hits CD 1990 Barenaked Ladies Disc One 1991-2001 CD 2001 Maroon CD 2000 Bauhaus The Sky's Gone Out CD 1988 Tuesday, January 23, 2007 Page 2 of 40 Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 1979-1983: Volume One CD 1986 In The Flat Field CD 1980 Beastie Boys Ill Communication CD 1994 Check Your Head CD 1992 Paul's Boutique CD 1989 Licensed To Ill CD 1986 Beatles, The Sgt