Comparative Destination Vulnerability Assessment for Khao Lak, Patong Beach and Phi Phi Don

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ryday 24 Hrs. At.Or.Th Nd.Org

Krabi Ko Lanta Yai Information by: TAT Krabi Tourist Information Division (Tel. 0 2250 5500 ext. 2141-5) Designed & Printed by: Marketing Services Department. 24 hrs. Everyday The contents of this publication are subject to change without notice. Tourist information by fax available 24 hrs. 2015 Copyright. No commercial reprinting of this material allowed. e-mail: [email protected] July 2017 www.tourismthailand.org cover.indd All Pages 30/10/2560 20:41:32 Krabi Krabi CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 8 Attractions 9 Amphoe Mueang Krabi 9 Amphoe Ao Luek 21 Amphoe Khlong Thom 23 Amphoe Ko Lanta 26 Amphoe Nue Khlong 29 Community based Tourism 29 Events and Festivals 31 Local Products and Souvenirs 32 Suggested Itinerary 32 Facilities 33 Accommodations 33 Restaurants 54 Useful Calls 66 Ko Ha KRABI Thai Term Glossary spelled diff erently. When seeking help from a Thai Amphoe : District for directions, point to the Thai spellings given Ao : Bay after each place name. Ban : Village Krabi, a coastal province, abounds with count- Chedi : Stupa or Pagoda less natural attractions that never fail to impress Hat : Beach tourists. Such attractions include white sandy Khao : Mountain beaches, crystal clear water, fascinating coral Khlong : Canal reefs, caves and waterfalls, as well as, numer- Ko : Island ous islands. Laem : Cape Mueang : Town or City From archaeological discoveries, it is believed Namtok : Waterfall that Krabi was one of the oldest communities in Tambon : Sub-district Thailand dating back to the prehistoric period. Wat : Temple It is believed that this town may have taken its name after the meaning of Krabi, which means Note: English spelling here given tries to approxi- sword. -

THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK

ROUGH GUIDES THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK N I H T O DUSIT AY EXP Y THANON L RE O SSWA H PHR 5 A H A PINKL P Y N A PRESSW O O N A EX H T Thonburi Democracy Station Monument 2 THAN BANGLAMPHU ON PHE 1 TC BAMRUNG MU HABURI C ANG h AI H 4 a T o HANO CHAROEN KRUNG N RA (N Hualamphong MA I EW RAYAT P R YA OAD) Station T h PAHURAT OW HANON A PL r RA OENCHI THA a T T SU 3 SIAM NON NON PH KH y a SQUARE U CHINATOWN C M HA H VIT R T i v A E e R r X O P E N R 6 K E R U S N S G THAN DOWNTOWN W A ( ON RAMABANGKOK IV N Y E W M R LO O N SI A ANO D TH ) 0 1 km TAKSIN BRI DGE 1 Ratanakosin 3 Chinatown and Pahurat 5 Dusit 2 Banglamphu and the 4 Thonburi 6 Downtown Bangkok Democracy Monument area About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The colour section is designed to give you a feel for Bangkok, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The city chapters cover each area of Bangkok in depth, giving comprehensive accounts of all the attractions plus excursions further afield, while the listings section gives you the lowdown on accommodation, eating, shopping and more. -

Do You Want to Travel Different? 50 Great Great 50 Green Escapes Green Become a Green Traveller Today

THAILAND DO YOU WANT TO TRAVEL DIFFERENT? 50 GREAT GREEN ESCAPES BECOME A GREEN TRAVELLER TODAY By visiting the destinations highlighted in this guidebook, and by reporting your impressions and comments to www.tourismthailand.org/7greens you will help the Tourism Authority of Thailand promote and preserve the country’s natural wonders. THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT. Become a Green Traveller Today Tourism Authority of Thailand Published and distributed by Tourism Authority of Thailand Attractions Promotion Division Product Promotion Department. Editor: Richard Werly / AsieInfo Ltd, ITF Silom Palace, 163/658 Silom Road, Bangkok 10500. Producer: Titaya Jenny Nilrungsee Assistant editor: Thanutvorn Jaturongkavanich Assistant producer: Janepoom Chetuphon Design & Artwork: Tistaya Nakneam Writer: Chandra Hope Heartland Special Thanks: Simon Bowring, TAT Photo Bank, Solomon Kane Copyright © 2010 Tourism Authority of Thailand. Thailand Tourism Awards (www.tourismthailand.org/tourismawards) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system without prior permission in writing from Tourism Authority of Thailand. ISBN: 978-974-679-200-4 Printed in Thailand by Amarin Printing and Publishing Public Company Limited. Seven The production of this book was done in strict compliance with forward thinking environmental the initiatives from the team. It was created using recyclable environmentally -

26178938.Pdf

Thappud Sarasin Bridge Khao Lak Ao Luk Yacht haven Marina Thepkassatri Road Andanman Sea Water Village Kok Kloi James Bond Island Sak Cape Khao Phanom Mai Khao Phang-Nga Bay Beach Phuket Int’l Airport National Park Khao Phanom Benja National Park Koh Hong Thai Rat Cape Sirinath Huay To Waterfall National Park Blue Canyon Kung Bay Koh Panak Nai Yang Beach Mission Hills d a Sai Cape o R i r Helipad t a s Ao Po Grand Marina s a Koh Yao Noi k Koh Reat p e Krabi Airport h T Naithon Beach Kho Phra Taew National Park Po Bay Thalang Bang Pae Waterfall Krabi City Nua Klaong Koh kala Ton Sai Waterfall Layan Phuket T h Layan Beach e Airpark p Bang Rong Bay k a s s Koh Yao Yai a Klong Thom t Ao Pranang ri R o a Paklok Bang Tao Beach Laguna d Phuket Koh Poda Heroines' Son Cape Monument Yamu Cape Island Koh Kai Cherngtalay Srisoonthorn Road Surin Beach Sing Cape Tha Ruea Boat Lagoon Marina Koh Si Bo Ya Royal Phuket Marina Kamala Beach Koh Rang Yai Tha Ruea Bay Hua Lan Cape Hin Koh Yung d Koh Phai a Cape o Koh Maphrao R Kathu Waterfall s s Loch Palm a P y Koh Pu B Sapam Tourist Thepkassatri Road Police Kalim Beach d Kathu Ph oa ra Baramee R Koh Phi Phi Don Patong Beach Phuket Country Club Homeworks Koh Koh Phi Phi Le Bang Wad Dam Phuket Sire King Rama Freedom Bay IX Park City Copyright Ltd 2004© Image Co Events Asia Sakdidej Kwang VichitRd. -

No Buildings on Lands Over 80 Meters Above Sea Level? - a Case Study of Kamala, Phuket

No buildings on lands over 80 meters above sea level? - a case study of Kamala, Phuket Somporn ONTHONG 1*, Sangdao WONGSAI 2 1*Graduate student, Faculty of Technology and Environment Prince of Songkla University, Phuket Campus 2Andaman Environment and Natural Disaster Research Center (ANED), of Technology and Environment Prince of Songkla University, Phuket Campus 80 Moo 1 Vichit Songkram Rd., Amphur Kathu, Phuket 83120, Thailand; Tel: +66-676-276-142; Fax. +66-7627-6002 E-mail: [email protected] *, 1*, [email protected] 2 Abstract A current issue on Phuket-stay-green above 80 meters from sea level is controversial among property investors and environmentalists. This study addressed this problem posed by mapping land uses at the elevated zones determined by the provincial policy and regulation. A case study was carried out for Kamala sub-district, Phuket, the South of Thailand. The Geoeye satellite image accessed in January 2011 was used to classify land use and land cover types. Field survey was conducted for the accuracy assessment of land use and land cover mapping. Four zones were 0-40 meters, 40-80 meters, 80-125 meters and above 125 meters from sea level. Our findings emphasize that the lands at the elevated zones 0-40 meters and 40-80 meters were mainly categorized as bare lands. These lands have not yet been filled up as the investors have overstated. There would be no need to revise the policy and regulation for allowing the buildings and constructions on the lands above 80 meters. Future land use policy and management should consider a balance between the development and environmental protection. -

Tourism Planning and Destination Marketing: Towards a Community-Driven Approach a Case of Thailand

Tc.urism Planning and Destination Marketing: Towards a Community-Driven Approach A Case of Thailand A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy At Lincoln University By Jutamas (Jantarat) Wisansing Lincoln University 2004 Abstract of a thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Tourism Planning and Destination Marketing: Towards a Community-Driven Approach A Case of Thailand By Jutamas (Jantarat) Wisansing This thesis argues that while analysing markets and developing strategies to exploit the external market place and to attract tourists remains a central focus for tourism marketers, it is not enough on its own to achieve sustainable tourism destination development. The researcher substantiates this argument by exploring the 'participatory tourism planning' concept in detail. Based on this approach, the community is identified as a primary customer for whom tourism marketers have ignored involving in their marketing attention, messages and programmes. The fundamental concept - marketing orientation and customer orientation - combined with emerging marketing theories were reviewed.in order to help examine how destination marketing, a community-driven approach, should be implemented within a destination area. This examination of marketing and community based tourism planning set a platform for this research. This analysis examines relevance, applicability and potential for an integration of these two pervasive approaches for tourism planning. ii Guided by the theoretical examination, an integrated community-based tourism planning and marketing model was proposed. In order to explore gaps between the proposed model and its practicality, three destination areas (Phuket, Samui and Songkla-Hatyai) in Thailand were studied and evaluated. -

Some Notes on Global Tourism Impacts

The Thailand Tsunami and Hurricane Katrina: A Preliminary Assessment of Their Impact and Meaning in Global Tourism Thomas A. Birkland, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, NY Pannapa Herabat, Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok Richard G. Little, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA William A. Wallace, Rensselear Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY Prepared for the Third Magrann Conference on ‘The Future of Disasters in a Globalizing World.’ Rutgers University April 2006 Birkland, Herabat, Little and Wallace—Page 2 Introduction In the short space of eight months between December 26, 2004 and August 29, 2005, two world-famous and prominent tourism locations, Southern Thailand and the United States Gulf Coast, were devastated by major natural disasters. These events captured worldwide attention, not only because of the tragic human story of people killed and lives disrupted, but also because so many people were familiar with these regions through their personal tourism experiences. It is this familiarity, coupled with the real-time availability of information on unfolding events made possible through television and the Internet that made these disasters truly global in their impact. As a result, these regions suffered a double blow; first the damage caused by the event itself and then a substantial drop-off in tourism visits. This drop-off was a result both of the physical loss of tourism facilities and more interestingly, the perception—sometimes justified but oftentimes not—that the area either is unsafe because of the damage or that the area is inherently dangerous because of the high likelihood of a similar event occurring in the future. -

Community-Based Tourism: a Strategy for Sustainable Tourism Development of Patong Beach, Phuket Island, Thailand

Asian Social Science; Vol. 11, No. 27; 2015 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Community-Based Tourism: A Strategy for Sustainable Tourism Development of Patong Beach, Phuket Island, Thailand Maythawin Polnyotee1 & Suwattana Thadaniti1 1 Interdisciplinary program in Environment, Development and Sustainability, Graduate School, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand 2 Chulalongkorn University Social Research Institute, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand Correspondence: Maythawin Polnyotee, Interdisciplinary program in Environment, Development and Sustainability, Graduate School, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 25, 2015 Accepted: October 16, 2015 Online Published: November 20, 2015 doi:10.5539/ass.v11n27p90 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n27p90 Abstract This study proposes community-based tourism as a strategy for sustainable tourism development of Patong Beach. Direct observation, questionnaire and interview are research instruments. A result of analyzing 120 questionnaires of local people which displayed a negative impact including economic impact which was very high ( x = 4.53), social impact ( x = 4.28 )and environmental impact ( x = 4.42) which were high so the total mean score was high ( x = 4.41). The Community-Based Tourism was adapted for solution all negative impacts which were mentioned earlier. The sreategies are namely 1. Political development strategy: (1.1) Enabling the participation of local people, (1.2) Giving the power of the community over the outside and (1.3) Ensuring rights in natural resource management. 2. Environmental development strategy: (2.1) Studying the carrying capacity of the area, (2.2) Managing waste disposal and (2.3) Raising awareness of the need for conservation.3. -

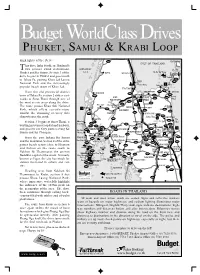

Phuket &Krabi Loop

Budget WorldClass Drives PHUKET, SAMUI & KRABI LOOP Highlights of the Drive 4006 KO PHANGAN G U L F O F T H A I L A N D his drive links Southern Thailand’s T two premier island destinations, A N D A M A N Ban Chaweng Mu Ko Ang Thong Phuket and Ko Samui. Section 1 of the S E A KAPOE THA CHANA KO SAMUI drive begins in Phuket and goes north Ban Nathon to Takua Pa, passing Khao Lak Lamru 4169 CHAIYA 4170 National Park and the increasingly Phum Riang 4 Ferry popular beach resort of Khao Lak. DON SAK THA CHANG 4142 From the old provincial district KANCHANADIT 4142 KHANOM KURA BURI 41 PHUNPHIN 4232 town of Takua Pa, section 2 strikes east- 4 401 4014 Hat Nai KHIRI SURAT 4010 wards to Surat Thani through one of RATTANIKHOM THANI Phlao 401 3 the most scenic areas along the drive. 4134 4100 Khao Sok Rachaphrapha 41 The route passes Khao Sok National KHIAN SA SICHON TAKUA PA Dam SAN NA DOEM 2 401 4106 Park, which offers eco-adventure BAN TAKHUN 4009 401 4133 amidst the stunning scenery that 4032 PHANOM BAN NA SAN 4188 4186 characterises the park. Krung Ching NOPPHITAM KAPONG 415 4140 THA Khao Lak WIANG SA (roads closed) SALA Section 3 begins at Surat Thani, a 4090 Lam Ru 4035 PHRA PHIPUN 4141 bustling provincial capital and harbour, 4240 4090 PHLAI PHRAYA 4016 4 4197 SAENG PHROMKHIRI 4013 4133 4015 5 and goes to car-ferry ports serving Ko 4 PHANG NGA 4035 CHAI BURI NAKHON SRI Hat Thai THAP PHUT 4228 Khao Samui and Ko Phangan. -

Why Are Women More Vulnerable During Disasters?

Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development APWLD NGO in consultative status at UN ECOSOC WHY ARE WOMEN MORE VULNERABLE DURING DISASTERS? Violations of Women’s Human Rights in the Tsunami Aftermath 1 Introduction October 2005 This report is a joint effort of women’s organisations and groups involved in relief, rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts in the countries affected by the Indian Ocean Tsunami on December 26, 2004. Representatives of women’s organisations participating at the Asian Civil Society Consultation on Post Tsunami Challenges in Bangkok, February 13-14, 2005, from India, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, Sri Lanka and Maldives felt there is a need for a comprehensive report focusing on women’s human rights violations in the tsunami aftermath given the gravity of the violations and the extent of marginalisation and exclusion of women from the rehabilitation process. We would like to make special acknowledgements to Titi Soentoro of Solidaritas Perempuan (Indonesia), Fatima Burnad of Society for Rural Education and Development (India), Pranom Somwong of Migrant Action Program (Thailand), Wanee Bangprapha of Culture and Peace Foundation (Thailand) and Sunila Abeysekera of INFORM (Sri Lanka) for their inputs to the report with detailed testimonies. The objectives of the report are: · to express our deep concern with violations of women’s human rights in the tsunami affected countries: Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Burma. · to draw the attention of the United Nations - a coordinating agency of the international support to the countries affected by the tsunami, governments of the affected countries, national and international non-governmental organisations involved in rehabilitation and reconstruction processes to violations of women’s human rights and women’s specific needs that must be adequately addressed during rehabilitation process. -

Phuket Sustainability Indicator Report Seeking a Sustainable Phuket

Phuket Sustainability Indicator Report SEEKing a Sustainable Phuket Phuket Sustainability Indicator Report 2013 Executive Partners Annual Sponsors Media Partners Hospitality Partners 2 NGO Partners Government Agencies Partner Companies 3 Phuket Sustainability Indicator Report 2013 Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Foreword ......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 What is SEEK Phuket? ............................................................................................................................................ 10 Phuket’s Development Dilemma ................................................................................................................. 11 The Sustainability Compass for Phuket Island ...................................................................................... 13 Our Sustainability Indicators ............................................................................................................................ -

Part 2 Thailand's Response to the Tsunami

Thousands of fishing boats, boat engines and fishing gear important to local livelihoods have been replaced through various programmes. Photo shows repaired boats in the Chao Lay village of Hin Look Dieu, Phuket. Photo: UNDP PREFACE The tragedy of the tsunami that struck Thailand’s Andaman coast on 26 December 2004, and the devastation and misery it left in its wake, is unprecedented in recent history. This disaster also brought forth an extraordinary response. Thailand, under the strong leadership of the Royal Thai Government (RTG), provided effective, efficient and comprehensive relief and humanitarian assistance to the Thai people, as well as to the large number of foreigners affected by the disaster. The scale of the disaster was matched by the generosity of the Thai people, who came forward to assist the victims of the tragedy in an extraordinary display of humanity. The Thai private sector and local NGOs also played a major role in the relief and recovery effort. Organizations and individuals from around the world contributed money and resources in support of Thailand’s response to the tsunami, and the world gratefully acknowledged the role of the RTG in dealing with the tragedy and its aftermath. Given its capacity and resources, Thailand did not appeal for international financial assistance. The international community has therefore played a relatively small but strategic role in Thailand’s tsunami recovery. The United Nations Country Team (UNCT), bilateral development agencies, and international NGOs have contributed structured support to the Royal Thai Government’s recovery efforts in areas where the RTG welcomed support from international partners: providing technical support, equipment, and direct support to the affected communities.