Contemporary Taiko Performance in Japan I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“SR-JV80 Collection Vol.4 World Collection” Wave Expansion Boar

SRX-09_je 1 ページ 2005年2月21日 月曜日 午後4時16分 201a Before using this unit, carefully read the sections entitled: “USING THE UNIT SAFELY” and “IMPORTANT NOTES” (p. 2; p. 4). These sections provide important information concerning the proper operation of the unit. Additionally, in order to feel assured that you have gained a good grasp of every feature provided by your new unit, Owner’s manual should be read in its entirety. The manual should be saved and kept on hand as a convenient reference. 201a この機器を正しくお使いいただくために、ご使用前に「安全上のご注意」(P.3)と「使用上のご注意」(P.4)をよく お読みください。また、この機器の優れた機能を十分ご理解いただくためにも、この取扱説明書をよくお読みくださ い。取扱説明書は必要なときにすぐに見ることができるよう、手元に置いてください。 Thank you, and congratulations on your choice of the SRX-09 このたびは、ウェーブ・エクスパンション・ボード SRX-09 “SR-JV80 Collection Vol.4 World Collection” Wave 「SR-JV80 Collection Vol.4 World Collection」をお買い上 Expansion Board. げいただき、まことにありがとうございます。 This expansion board contains all of the waveforms in the このエクスパンション・ボードは SR-JV80-05 World、14 World SR-JV80-05 World, SR-JV80-14 World Collection “Asia,” and Collection "Asia"、18 World Collection "LATIN" に搭載されていた SR-JV80-18 World Collection “LATIN,” along with specially ウェーブフォームを完全収録、17 Country Collection に搭載されて selected titles from waveforms contained in the 17 Country いたウェーブフォームから一部タイトルを厳選して収録しています。 Collection. This board contains new Patches and Rhythm これらのウェーブフォームを組み合わせた SRX 仕様の Sets which combine the waveforms in a manner that Effect、Matrix Control を生かした新規 パッチ、リズム・ highlights the benefits of SRX Effects and Matrix Control. セットを搭載しています。 This board contains all kinds of unique string, wind, and アフリカ、アジア、中近東、南米、北米、オーストラリア、 percussion instrument sounds, used in ethnic music from ヨーロッパ等、世界中のユニークで様々な弦楽器、管楽器、 Africa, Asia, the Middle East, South and North America, 打楽器などの各種民族楽器の音色を収録しています。 Australia, and Europe. -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Teachers' Notes:Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical

Teachers’ Notes: Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical Instruments Shakuhachi This Japanese flute with only five finger holes is made of the root end of a heavy variety of bamboo. From around 1600 through to the late 1800’s the shakuhachi was used exclusively as a tool for Zen meditation. Since the Meiji restoration (1868), the shakuhachi has performed in chamber music combinations with koto (zither), shamisen (lute) and voice. In the 20 th century, shakuhachi has performed in many types of ensembles in combination with non-Japanese instruments. It’s characteristic haunting sounds, evocative of nature, are frequently featured in film music. Koto (in Anne’s Japanese Music Show, not Taiko performance) Like the shakuhachi , the koto (a 13 stringed zither) ORIGINATED IN China and a uniquely Japanese musical vocabulary and performance aesthetic has gradually developed over its 1200 years in Japan. Used both in ensemble and as a solo virtuosic instrument, this harp-like instrument has a great tuning flexibility and has therefore adapted well to cross cultural music genres. Taiko These drums come in many sizes and have been traditionally associated with religious rites at Shinto shrines as well as village festivals. In the last 30 years, Taiko drumming groups have flourished in Japan and have become poplar worldwide for their fast pounding rhythms. Sasara A string of small wooden slats, which make a large rattling sound when played with a “whipping” action. Kane A small hand held gong. Chappa A small pair of cymbals Sasara Kane Bookings -

Balancing Japanese Musical Elements and Western Influence Within an Historical and Cultural Context

FENCE, FLAVOR, AND PHANTASM: BALANCING JAPANESE MUSICAL ELEMENTS AND WESTERN INFLUENCE WITHIN AN HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL CONTEXT Kelly Desjardins, B.M., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2018 APPROVED: Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Major Professor Darhyl Ramsey, Committee Member Dennis Fisher, Committee Member Nicholas Williams, Interim Chair of the Division of Conducting and Ensembles Warren Henry, Interim Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Desjardins, Kelly. Fence, Flavor, and Phantasm: Balancing Japanese Musical Elements and Western Influence within an Historical and Cultural Context. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2018, 99 pp., 14 tables, 44 musical examples, bibliography, 63 titles. Given the diversity found in today's Japanese culture and the size of the country's population, it is easy to see why the understanding of Japanese wind band repertoire must be multi-faceted. Alongside Western elements, many Japanese composers have intentionally sought to maintain their cultural identity through the addition of Japanese musical elements or concepts. These added elements provide a historical and cultural context from which to frame a composition or, in some cases, a composer's compositional output. The employment of these elements serve as a means to categorize the Japanese wind band repertoire. In his studies on cultural identities found in Japanese music, Gordon Matthews suggests there are three genres found within Japanese culture. He explains these as "senses of 'Japaneseness' among Japanese musicians." They include Fence, Flavor, and Phantasm. -

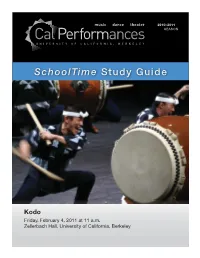

Kodo Study Guide 1011.Indd

2010–2011 SEASON SchoolTime Study Guide Kodo Friday, February 4, 2011 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime On Friday, February 4 at 11am, your class will att end a SchoolTime performance of Kodo (Taiko drumming) at Cal Performances’ Zellerbach Hall. In Japan, “Kodo” meana either “hearbeat” or “children of the drum.” These versati le performers play a variety of instruments – some massive in size, some extraordinarily delicate that mesmerize audiences. Performing in unison, they wield their sti cks like expert swordsmen, evoking thrilling images of ancient and modern Japan. Witnessing a performance by Kodo inspires primal feelings, like plugging into the pulse of the universe itself. Using This Study Guide You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Cal Performances fi eld trip. Before att ending the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the Student Resource Sheet on pages 2 & 3 for your students to use before the show. • Discuss the informati on on pages 4-5 About the Performance & Arti sts. • Read About the Art Form on page 6, and About Japan on page 11 with your students. • Engage your class in two or more acti viti es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect by asking students the guiding questi ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 11. • Immerse students further into the subject matt er and art form by using the Resource and Glossary secti ons on pages 15 & 16. At the performance: Your class can acti vely parti cipate during the performance by: • Listening to Kodo’s powerful drum rhythms and expressive music • Observing how the performers’ movements and gestures enhance the performance • Thinking about how you are experiencing a bit of Japanese culture and history by att ending a live performance of taiko drumming • Marveling at the skill of the performers • Refl ecti ng on the sounds, sights, and performance skills you experience at the theater. -

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: the Intercultural History of a Musical Genre

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre by Benjamin Jefferson Pachter Bachelors of Music, Duquesne University, 2002 Master of Music, Southern Methodist University, 2004 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences This dissertation was presented by Benjamin Pachter It was defended on April 8, 2013 and approved by Adriana Helbig Brenda Jordan Andrew Weintraub Deborah Wong Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung ii Copyright © by Benjamin Pachter 2013 iii Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre Benjamin Pachter, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation is a musical history of wadaiko, a genre that emerged in the mid-1950s featuring Japanese taiko drums as the main instruments. Through the analysis of compositions and performances by artists in Japan and the United States, I reveal how Japanese musical forms like hōgaku and matsuri-bayashi have been melded with non-Japanese styles such as jazz. I also demonstrate how the art form first appeared as performed by large ensembles, but later developed into a wide variety of other modes of performance that included small ensembles and soloists. Additionally, I discuss the spread of wadaiko from Japan to the United States, examining the effect of interactions between artists in the two countries on the creation of repertoire; in this way, I reveal how a musical genre develops in an intercultural environment. -

Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004

Music 17Q Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004 M W: 2:15 – 4:05 p.m., Braun 106 (M), Braun Rehearsal Hall (W) 4 units Course Syllabus Taiko, used here to refer to performance ensemble drumming using the taiko, or Japanese drum, is a relative newcomer to the American music scene. The emergence of the first North American groups coincided with increased activism in the Japanese American community and, to some, is symbolic of Japanese American identity. To others, North American taiko is associated with Japanese American Buddhism, and to others taiko is a performance art rooted in Japan. In this course we will explore the musical, cultural, historical, and political perspectives of taiko in North America through drumming (hands-on experience), readings, class discussions, workshops, and a research project. With taiko as the focal point, we will learn about Japanese music and Japanese American history, and explore relations between performance, cultural expression, community, and identity. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Students must attend all workshops and complete all assignments to receive credit for the course. Reaction Papers (30%) Midterm (20%) Research Project (40%) Attendance/Participation (10%) COURSE FEE $30 to partially cover cost of bachi, bachi bag, concert tickets, workshop fees, gas and parking for drivers. READINGS 1. Course reader available at the Stanford Bookstore. 2. Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Ronald Takaki. 1989. Penguin Books. GENERAL INFORMATION Instructors Steve Sano Linda Uyechi Office Braun 120 Office Phone 723-1570 Phone 494-1321 494-1321 (8 a.m. – 10 p.m.) Email sano@leland [email protected] 1 COURSE OUTLINE WEEK 1 (March 31) Wednesday Introduction: What is North American Taiko? Reading Terada, Y. -

A Performer's Guide to Minoru Miki's Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988)

University of Cincinnati Date: 4/22/2011 I, Margaret T Ozaki-Graves , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Voice. It is entitled: A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s _Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano_ (1988) Student's name: Margaret T Ozaki-Graves This work and its defense approved by: Committee chair: Jeongwon Joe, PhD Committee member: William McGraw, MM Committee member: Barbara Paver, MM 1581 Last Printed:4/29/2011 Document Of Defense Form A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988) A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Margaret Ozaki-Graves B.M., Lawrence University, 2003 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2007 April 22, 2011 Committee Chair: Jeongwon Joe, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Japanese composer Minoru Miki (b. 1930) uses his music as a vehicle to promote cross- cultural awareness and world peace, while displaying a self-proclaimed preoccupation with ethnic mixture, which he calls konketsu. This document intends to be a performance guide to Miki’s Sohmon III: for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988). The first chapter provides an introduction to the composer and his work. It also introduces methods of intercultural and artistic borrowing in the Japanese arts, and it defines the four basic principles of Japanese aesthetics. The second chapter focuses on the interpretation and pronunciation of Sohmon III’s song text. -

DRUMS S21 Medium Snare 2 Rim Shot S22 Concert Snare Soft Exc 1 Bass Drum (Kick) S23 Concert Snare Hard Exc 1 No

Information When you need repair service, call your nearest Roland Service Center or authorized Roland distributor in your country as shown below. SINGAPORE PANAMA ITALY ISRAEL AFRICA Swee Lee Company SUPRO MUNDIAL, S.A. Roland Italy S. p. A. Halilit P. Greenspoon & 150 Sims Drive, Boulevard Andrews, Albrook, Viale delle Industrie 8, Sons Ltd. EGYPT SINGAPORE 387381 Panama City, REP. DE PANAMA 20020 Arese, Milano, ITALY 8 Retzif Ha'aliya Hashnya St. Al Fanny Trading Office TEL: 846-3676 TEL: 315-0101 TEL: (02) 937-78300 Tel-Aviv-Yafo ISRAEL 9, EBN Hagar A1 Askalany Street, TEL: (03) 6823666 ARD E1 Golf, Heliopolis, CRISTOFORI MUSIC PTE PARAGUAY NORWAY Cairo 11341, EGYPT LTD Distribuidora De Roland Scandinavia Avd. JORDAN TEL: 20-2-417-1828 Blk 3014, Bedok Industrial Park E, Instrumentos Musicales Kontor Norge AMMAN Trading Agency #02-2148, SINGAPORE 489980 J.E. Olear y ESQ. Manduvira Lilleakerveien 2 Postboks 95 245 Prince Mohammad St., REUNION TEL: 243 9555 Asuncion PARAGUAY Lilleaker N-0216 Oslo Amman 1118, JORDAN Maison FO - YAM Marcel TEL: (021) 492-124 NORWAY TEL: (06) 464-1200 25 Rue Jules Hermann, TAIWAN TEL: 273 0074 Chaudron - BP79 97 491 ROLAND TAIWAN PERU KUWAIT Ste Clotilde Cedex, ENTERPRISE CO., LTD. VIDEO Broadcast S.A. POLAND Easa Husain Al-Yousifi REUNION ISLAND Room 5, 9fl. No. 112 Chung Shan Portinari 199 (ESQ. HALS), P. P. H. Brzostowicz Abdullah Salem Street, TEL: (0262) 218-429 N.Road Sec.2, Taipei, TAIWAN, San Borja, Lima 41, UL. Gibraltarska 4. Safat, KUWAIT R.O.C. REP. OF PERU PL-03664 Warszawa POLAND TEL: 243-6399 SOUTH AFRICA TEL: (02) 2561 3339 TEL: (01) 4758226 TEL: (022) 679 44 19 That Other Music Shop LEBANON (PTY) Ltd. -

Kanji-West-Notation-090214

TaikoSource.Com Collected by Taiko.biz / 2014 Taiko Notation Project (…a work in progress)* Kuchi-shōga (“mouth writing,” also kuchi-shoka/kuchi-shouga/kuchi-showa depending on the area of Japan or tradition) is a phonetic system used to teach most Japanese instruments. Each note or sound that an instrument produces is assigned a different syllable. It is often said: "if you can say it, you can play it." For example, the syllable "Don" refers to striking the middle of the drumhead (hara), while "Ka" refers to striking the wood- backed edge of the drumhead (fuchi).1 Kanji > Kuchi-shōga2 > Western Notes: Quick reference chart When: =1 [or =1] (Fonts: MusiSync, Zapf Dingbats, MS PMingLiU) Chu / Sumo Quiet & Rest/Ma ドン Don [or ] ツ tsu ( ) [or ( )] ドコ DoKo [or ] ツク tsuku [or ] カ Ka [or ] イヤ i-ya Q Q [or Q ] カラ KaRa [or ] ス su Q [or E or S ] Shime Atarigane (Chan Chiki) 天 Ten [or ] m Cha [or ] テケ TeKe [or ] mン Chan [or ] l Chi [or ] l–l ChiKi [or ] *Always check TaikoSource.com for most up-to-date version. This is a living document and will change as information is gathered. The chart above is the most commonly used notation for quick reference. For more detailed and extended information, see next pages…. 1 Original text from Rolling Thunder: http://www.taiko.com/taiko_resource/learn.html 2 Some text from Kaoru Watanabe Taiko Center: http://www.taikonyc.com/kuchishouga/ September 2, 2014 1 TaikoSource.Com Collected by Taiko.biz / 2014 For the purposes of the following detailed charts, the “one” count in each group (ex. -

Taiko and the Asian/American Body: Drums, "Rising Sun," and the Question of Gender Author(S): Deborah Wong Source: the World of Music, Vol

Bärenreiter Florian Noetzel GmbH Verlag Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG VWB - Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung Taiko and the Asian/American Body: Drums, "Rising Sun," and the Question of Gender Author(s): Deborah Wong Source: The World of Music, Vol. 42, No. 3, Local Musical Traditions in the Globalization Process (2000), pp. 67-78 Published by: VWB - Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41692766 Accessed: 22-06-2016 16:14 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Bärenreiter, Florian Noetzel GmbH Verlag, Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG, VWB - Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The World of Music This content downloaded from 138.23.232.112 on Wed, 22 Jun 2016 16:14:57 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms the world of music 42(3)- 2000 : 67-78 Taiko and the Asian/American Body: Drums, Rising Sun , and the Question of Gender Deborah Wong Abstract This essay addresses the Japanese tradition of taiko drumming as an Asian American practice inflected by transnational discourses of orientalism and colonialism. I argue that the potential in taiko for slippage between the Asian and the Asian American body is both problematic and on-going , and that the body of the taiko player is gendered and racialized in complex ways . -

Court Music by Shiba Sukeyasu

JAPANESE MIND Japan’s Ancient Court Music By Shiba Sukeyasu Photos: Music Department, Imperial Household Agency Origin of Gagaku : Ancient Gala Concert A solemn ceremony was held at Todai-ji – a majestic landmark Buddhist temple – in the ancient capital of Nara 1,255 years ago, on April 9 in 752, to endow a newly completed Great Buddha statue with life. The ceremony was officiated by a high Buddhist priest from India named Bodhisena (704-760), and attended by the Emperor, members of the Imperial Family, noblemen and high priests. Thousands of pious people thronged the main hall of the temple that houses the huge Buddha image to “Gagaku” is performed by members of the Music Department of the express their joy in the event. Imperial Household Agency. Traditionally, kakko (right in the front row) On the stage set up in the foreground is always played by the oldest band member. of the hall, a gala celebratory concert was staged and performing arts from Tang music that he aspired to learn the instruments various parts of Asia were introduced. music in Tang. Legend has it that his were three wind Outstanding among them was Chinese wish was finally granted in 835 when he instruments – music called Togaku (music of the Tang was aged 103. His willpower was sho (mouth organ), hichiriki (oboe) and Dynasty). Clad in colorfully unruffled by his old age and he returned ryuteki (seven-holed flute) –, two string embroidered gorgeous silk costumes, to Japan after learning music and instruments – biwa (lute) and gakuso Chinese musicians played 18 different dancing for five years.