TAIKOPROJECT Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BCA Voices - August 27, 1981 by Rev

The Newsletter of Ekoji Buddhist Temple alavinka Fairfax Station, Virginia - Established 1981 Vol. XXXIII, No. 7 July 2014 BCA Voices - August 27, 1981 By Rev. Kenryu Tsuji This month, we are changing the column up a little heat, it gave shelter to countless insects, even giving and including a poem by Rev. Kenryu Tsuji, former a part of itself to the hungry bugs. Ekoji Resident Minister and former Bishop of the Bud- And now, it is that time of the year. dhist Churches of America. According to Ekoji’s for- mer librarian, Valorie Lee, this piece “is one of Rev. But before it falls from its branch, it prepares for the Tsuji’s writings that may be the closest he ventured in future, for next spring, a fresh green leaf will shoot the direction of poetry. It originally appeared in the out from the same branch. In its twilight hours it Kalavinka and then was included in The Heart of the displayed to the world, without pride, without self- Buddha Dharma. Not titled in the Kalavinka, but re- consciousness, its ultimate beauty. quiring one for the book, I used the date of the Kala- vinka issue in which it appeared.” Does the human spirit grow more beautiful with each passing day? Or does it become more engrossed August 27, 1981 in its mortality by creating stronger hands of self- attachment? It is that time of the year. Is my life reflecting a deeper beauty as I grow older? A single red maple leaf performs a graceful ballet What karmic influences will I leave for the good of in the cool autumn breeze before it finally joins the the world? other leaves on the ground. -

ANACHRONE 2007 Les GARDIENS DU SEUIL

ANACHRONE 2007 Les GARDIENS DU SEUIL L’EMPIRE SCARABEE © ANACHRONE 2007 1 ANACHRONE 2007 Les GARDIENS DU SEUIL Carte de l’Empire avant la Guerre Civile (octobre 1105) L’EMPIRE SCARABEE © ANACHRONE 2007 2 ANACHRONE Les GARDIENS DU SEUIL 2007 Rouge : « alliance Rebelles de MON DES CLANS DE L’EMPIRE Zanonaï » (avant la Guerre Civile) Bleu : « Faction Impériale » Rose : clans neutres / indécis (1) Mutsu (2) Dewa (3) Echigo (4) Shimotsuke (5) Yasuki (6) Gogenso (7) Hitashi (8) Awa (9) Kotsuke (10) Sagami (9) Kotsuke (après oct. 1105) (11) Izu Daimyo mort pendant la guerre, son gendre du clan (12) Kai (14) Suriga (15) Etchu Sugiga a hérité du fief (12) Kai (15) Etchu (après oct. 1105) (après oct. 1105) (13) Shinano (18) Totomi (18) Totomi (19) Mikawa (16) Noto (17) Shimosa (après oct. 1105) (19) Mikawa (après oct. 1105) (20) Saïcho Owari (21) Mimasaki (22) Nagato (23) Satsuma (clan dissous en oct.1105, le fief appartient au clan Sagami) L’EMPIRE SCARABEE © ANACHRONE 2007 3 ANACHRONE 2007 Les GARDIENS DU SEUIL Carte de l’Empire après la Guerre Civile (juin 1107) L’EMPIRE SCARABEE © ANACHRONE 2007 4 ANACHRONE Les GARDIENS DU SEUIL 2007 MON DES CLANS DE L’EMPIRE (après la Guerre Civile – juin 1107) (6) (3) (17) (10) (4) (7) (23) (20) (19) (5) Gogenso Sagami Saïcho Owari Yasuki (12) (15) (14) (11) (21) (9) (2) Kai Suriga Kotsuke (13) (8) Shinano (16) (22) (18) (1) Noto Nagato Totomi L’EMPIRE SCARABEE © ANACHRONE 2007 5 ANACHRONE 2007 Les GARDIENS DU SEUIL L’EMPIRE SCARABEE L’Empire Scarabée est une contrée rocailleuse et vallonnée, cernée à ses frontières Nord par une chaîne de montagnes (Monts Tatsu, cette région montagneuse abrite environ une centaine de volcans, dont une vingtaine est encore en activité, mais également de nombreuses sources d’eau chaude) ; au Sud, à l’Ouest et à l’Est, par un océan. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90w6w5wz Author Carter, Caleb Swift Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Caleb Swift Carter 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries by Caleb Swift Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor William M. Bodiford, Chair This dissertation considers two intersecting aspects of premodern Japanese religions: the development of mountain-based religious systems and the formation of numinous sites. The first aspect focuses in particular on the historical emergence of a mountain religious school in Japan known as Shugendō. While previous scholarship often categorizes Shugendō as a form of folk religion, this designation tends to situate the school in overly broad terms that neglect its historical and regional stages of formation. In contrast, this project examines Shugendō through the investigation of a single site. Through a close reading of textual, epigraphical, and visual sources from Mt. Togakushi (in present-day Nagano Ken), I trace the development of Shugendō and other religious trends from roughly the thirteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries. This study further differs from previous research insofar as it analyzes Shugendō as a concrete system of practices, doctrines, members, institutions, and identities. -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Teachers' Notes:Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical

Teachers’ Notes: Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical Instruments Shakuhachi This Japanese flute with only five finger holes is made of the root end of a heavy variety of bamboo. From around 1600 through to the late 1800’s the shakuhachi was used exclusively as a tool for Zen meditation. Since the Meiji restoration (1868), the shakuhachi has performed in chamber music combinations with koto (zither), shamisen (lute) and voice. In the 20 th century, shakuhachi has performed in many types of ensembles in combination with non-Japanese instruments. It’s characteristic haunting sounds, evocative of nature, are frequently featured in film music. Koto (in Anne’s Japanese Music Show, not Taiko performance) Like the shakuhachi , the koto (a 13 stringed zither) ORIGINATED IN China and a uniquely Japanese musical vocabulary and performance aesthetic has gradually developed over its 1200 years in Japan. Used both in ensemble and as a solo virtuosic instrument, this harp-like instrument has a great tuning flexibility and has therefore adapted well to cross cultural music genres. Taiko These drums come in many sizes and have been traditionally associated with religious rites at Shinto shrines as well as village festivals. In the last 30 years, Taiko drumming groups have flourished in Japan and have become poplar worldwide for their fast pounding rhythms. Sasara A string of small wooden slats, which make a large rattling sound when played with a “whipping” action. Kane A small hand held gong. Chappa A small pair of cymbals Sasara Kane Bookings -

Catalogue 229 Japanese and Chinese Books, Manuscripts, and Scrolls Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller New York City

JonathanCatalogue 229 A. Hill, Bookseller JapaneseJAPANESE & AND Chinese CHINESE Books, BOOKS, Manuscripts,MANUSCRIPTS, and AND ScrollsSCROLLS Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller Catalogue 229 item 29 Catalogue 229 Japanese and Chinese Books, Manuscripts, and Scrolls Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller New York City · 2019 JONATHAN A. HILL, BOOKSELLER 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10 b New York, New York 10023-8143 telephone: 646-827-0724 home page: www.jonathanahill.com jonathan a. hill mobile: 917-294-2678 e-mail: [email protected] megumi k. hill mobile: 917-860-4862 e-mail: [email protected] yoshi hill mobile: 646-420-4652 e-mail: [email protected] member: International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America & Verband Deutscher Antiquare terms are as usual: Any book returnable within five days of receipt, payment due within thirty days of receipt. Persons ordering for the first time are requested to remit with order, or supply suitable trade references. Residents of New York State should include appropriate sales tax. printed in china item 24 item 1 The Hot Springs of Atami 1. ATAMI HOT SPRINGS. Manuscript on paper, manuscript labels on upper covers entitled “Atami Onsen zuko” [“The Hot Springs of Atami, explained with illustrations”]. Written by Tsuki Shirai. 17 painted scenes, using brush and colors, on 63 pages. 34; 25; 22 folding leaves. Three vols. 8vo (270 x 187 mm.), orig. wrappers, modern stitch- ing. [ Japan]: late Edo. $12,500.00 This handsomely illustrated manuscript, written by Tsuki Shirai, describes and illustrates the famous hot springs of Atami (“hot ocean”), which have been known and appreciated since the 8th century. -

Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7hf4q6w5 Journal Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, 1(3) Author Dessen, MJ Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, Vol 1, No 3 (2006) Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies Michael Dessen, Hampshire College Introduction Throughout the twentieth century, African American improvisers not only created innovative musical practices, but also—often despite staggering odds—helped shape the ideas and the economic infrastructures which surrounded their own artistic productions. Recent studies such as Eric Porter’s What is this Thing Called Jazz? have begun to document these musicians’ struggles to articulate their aesthetic philosophies, to support and educate their communities, to create new audiences, and to establish economic and cultural capital. Through studying these histories, we see new dimensions of these artists’ creativity and resourcefulness, and we also gain a richer understanding of the music. Both their larger goals and the forces working against them—most notably the powerful legacies of systemic racism—all come into sharper focus. As Porter’s book makes clear, African American musicians were active on these multiple fronts throughout the entire century. Yet during the 1960s, bolstered by the Civil Rights -

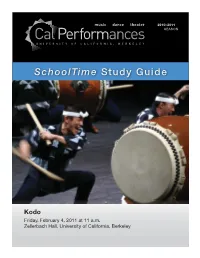

Kodo Study Guide 1011.Indd

2010–2011 SEASON SchoolTime Study Guide Kodo Friday, February 4, 2011 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime On Friday, February 4 at 11am, your class will att end a SchoolTime performance of Kodo (Taiko drumming) at Cal Performances’ Zellerbach Hall. In Japan, “Kodo” meana either “hearbeat” or “children of the drum.” These versati le performers play a variety of instruments – some massive in size, some extraordinarily delicate that mesmerize audiences. Performing in unison, they wield their sti cks like expert swordsmen, evoking thrilling images of ancient and modern Japan. Witnessing a performance by Kodo inspires primal feelings, like plugging into the pulse of the universe itself. Using This Study Guide You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Cal Performances fi eld trip. Before att ending the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the Student Resource Sheet on pages 2 & 3 for your students to use before the show. • Discuss the informati on on pages 4-5 About the Performance & Arti sts. • Read About the Art Form on page 6, and About Japan on page 11 with your students. • Engage your class in two or more acti viti es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect by asking students the guiding questi ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 11. • Immerse students further into the subject matt er and art form by using the Resource and Glossary secti ons on pages 15 & 16. At the performance: Your class can acti vely parti cipate during the performance by: • Listening to Kodo’s powerful drum rhythms and expressive music • Observing how the performers’ movements and gestures enhance the performance • Thinking about how you are experiencing a bit of Japanese culture and history by att ending a live performance of taiko drumming • Marveling at the skill of the performers • Refl ecti ng on the sounds, sights, and performance skills you experience at the theater. -

In North America

Shifting Identities of Taiko Music in North America }ibshitaka Zerada National Museum of Ethnology Many Japanese communities in North America hold a Bon (or O- bon) festival every summer, when the spirit of the deceased is summoned to the world ofthe living fbr entertainment of dance and music.i At such festivals, one often encounters a group of energetic and smiling perfbrmers playing various types of drums in tightly choreographed movements. The roaring sound of drums resembles `rolling thunder' and the joyous energy emanating from perfbrmers is captivating. The music they play is known as taiko, and approximately 150 groups are actively engaged in performing this music in North America today.2 This paper aims to provide a brief overview of the development of taiko music and to analyze the relationship between taiko music and the construction of identity among Asians in North America. 71aiko is a Japanese term that refers in its broadest sense to drums in general. In order to distinguish them from those of foreign origin, Japanese drums are often referred to as wadaiko, literally meaning `Japanese drum'. Although the roots ofwadaiko music may be traced to the drum and flute ensembles that accompanied Shinto rituals, agricultural rites, and Bon festivals in Japan for centuries, wadaiko has come to mean a new drumming style that developed after World War II out of the music played by such ensembles. North American taiko is based largely on this post-War wadaiko muslc, contrary to lts anclent lmage. Madaiko music is distinguished from previous drumming traditions in Japan by a style of communal playing known as kumidaiko, involving a multiple number of drummers and a set of taiko drums in various shapes and sizes. -

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: the Intercultural History of a Musical Genre

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre by Benjamin Jefferson Pachter Bachelors of Music, Duquesne University, 2002 Master of Music, Southern Methodist University, 2004 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences This dissertation was presented by Benjamin Pachter It was defended on April 8, 2013 and approved by Adriana Helbig Brenda Jordan Andrew Weintraub Deborah Wong Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung ii Copyright © by Benjamin Pachter 2013 iii Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre Benjamin Pachter, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation is a musical history of wadaiko, a genre that emerged in the mid-1950s featuring Japanese taiko drums as the main instruments. Through the analysis of compositions and performances by artists in Japan and the United States, I reveal how Japanese musical forms like hōgaku and matsuri-bayashi have been melded with non-Japanese styles such as jazz. I also demonstrate how the art form first appeared as performed by large ensembles, but later developed into a wide variety of other modes of performance that included small ensembles and soloists. Additionally, I discuss the spread of wadaiko from Japan to the United States, examining the effect of interactions between artists in the two countries on the creation of repertoire; in this way, I reveal how a musical genre develops in an intercultural environment. -

Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004

Music 17Q Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004 M W: 2:15 – 4:05 p.m., Braun 106 (M), Braun Rehearsal Hall (W) 4 units Course Syllabus Taiko, used here to refer to performance ensemble drumming using the taiko, or Japanese drum, is a relative newcomer to the American music scene. The emergence of the first North American groups coincided with increased activism in the Japanese American community and, to some, is symbolic of Japanese American identity. To others, North American taiko is associated with Japanese American Buddhism, and to others taiko is a performance art rooted in Japan. In this course we will explore the musical, cultural, historical, and political perspectives of taiko in North America through drumming (hands-on experience), readings, class discussions, workshops, and a research project. With taiko as the focal point, we will learn about Japanese music and Japanese American history, and explore relations between performance, cultural expression, community, and identity. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Students must attend all workshops and complete all assignments to receive credit for the course. Reaction Papers (30%) Midterm (20%) Research Project (40%) Attendance/Participation (10%) COURSE FEE $30 to partially cover cost of bachi, bachi bag, concert tickets, workshop fees, gas and parking for drivers. READINGS 1. Course reader available at the Stanford Bookstore. 2. Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Ronald Takaki. 1989. Penguin Books. GENERAL INFORMATION Instructors Steve Sano Linda Uyechi Office Braun 120 Office Phone 723-1570 Phone 494-1321 494-1321 (8 a.m. – 10 p.m.) Email sano@leland [email protected] 1 COURSE OUTLINE WEEK 1 (March 31) Wednesday Introduction: What is North American Taiko? Reading Terada, Y. -

From the City to the Mountain and Back Again: Situating Contemporary Shugendô in Japanese Social and Religious Life

From the City to the Mountain and Back Again: Situating Contemporary Shugendô in Japanese Social and Religious Life Mark Patrick McGuire A Thesis In The Department of Religion Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada April 2013 Mark Patrick McGuire, 2013 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Mark Patrick McGuire Entitled: From the City to the Mountain and Back Again: Situating Contemporary Shugendô in Japanese Social and Religious Life and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Religion) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. V. Penhune External Examiner Dr. B. Ambros External to Program Dr. S. Ikeda Examiner Dr. N. Joseph Examiner Dr. M. Penny Thesis Supervisor Dr. M. Desjardins Approved by Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director Dr. S. Hatley, Graduate Program Director April 15, 2013 Dr. B. Lewis, Dean, Faculty of Arts and Science ABSTRACT From the City to the Mountain and Back Again: Situating Contemporary Shugendô in Japanese Social and Religious Life Mark Patrick McGuire, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2013 This thesis examines mountain ascetic training practices in Japan known as Shugendô (The Way to Acquire Power) from the 1980s to the present. Focus is given to the dynamic interplay between two complementary movements: 1) the creative process whereby charismatic, media-savvy priests in the Kii Peninsula (south of Kyoto) have re-invented traditional practices and training spaces to attract and satisfy the needs of diverse urban lay practitioners, and 2) the myriad ways diverse urban ascetic householders integrate lessons learned from mountain austerities in their daily lives in Tokyo and Osaka.