Binary and Multiple Systems of Asteroids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Occultation Evidence for a Satellite of the Trojan Asteroid (911) Agamemnon Bradley Timerson1, John Brooks2, Steven Conard3, David W

Occultation Evidence for a Satellite of the Trojan Asteroid (911) Agamemnon Bradley Timerson1, John Brooks2, Steven Conard3, David W. Dunham4, David Herald5, Alin Tolea6, Franck Marchis7 1. International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA), 623 Bell Rd., Newark, NY, USA, [email protected] 2. IOTA, Stephens City, VA, USA, [email protected] 3. IOTA, Gamber, MD, USA, [email protected] 4. IOTA, KinetX, Inc., and Moscow Institute of Electronics and Mathematics of Higher School of Economics, per. Trekhsvyatitelskiy B., dom 3, 109028, Moscow, Russia, [email protected] 5. IOTA, Murrumbateman, NSW, Australia, [email protected] 6. IOTA, Forest Glen, MD, USA, [email protected] 7. Carl Sagan Center at the SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Av, Mountain View CA 94043, USA, [email protected] Corresponding author Franck Marchis Carl Sagan Center at the SETI Institute 189 Bernardo Av Mountain View CA 94043 USA [email protected] 1 Keywords: Asteroids, Binary Asteroids, Trojan Asteroids, Occultation Abstract: On 2012 January 19, observers in the northeastern United States of America observed an occultation of 8.0-mag HIP 41337 star by the Jupiter-Trojan (911) Agamemnon, including one video recorded with a 36cm telescope that shows a deep brief secondary occultation that is likely due to a satellite, of about 5 km (most likely 3 to 10 km) across, at 278 km ±5 km (0.0931″) from the asteroid’s center as projected in the plane of the sky. A satellite this small and this close to the asteroid could not be resolved in the available VLT adaptive optics observations of Agamemnon recorded in 2003. -

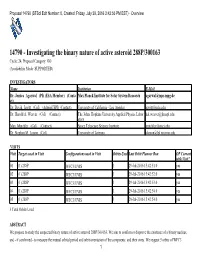

14790 (Stsci Edit Number: 0, Created: Friday, July 29, 2016 2:42:55 PM EST) - Overview

Proposal 14790 (STScI Edit Number: 0, Created: Friday, July 29, 2016 2:42:55 PM EST) - Overview 14790 - Investigating the binary nature of active asteroid 288P/300163 Cycle: 24, Proposal Category: GO (Availability Mode: SUPPORTED) INVESTIGATORS Name Institution E-Mail Dr. Jessica Agarwal (PI) (ESA Member) (Conta Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research [email protected] ct) Dr. David Jewitt (CoI) (AdminUSPI) (Contact) University of California - Los Angeles [email protected] Dr. Harold A. Weaver (CoI) (Contact) The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Labor [email protected] atory Max Mutchler (CoI) (Contact) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Dr. Stephen M. Larson (CoI) University of Arizona [email protected] VISITS Visit Targets used in Visit Configurations used in Visit Orbits Used Last Orbit Planner Run OP Current with Visit? 01 (1) 288P WFC3/UVIS 1 29-Jul-2016 15:42:51.0 yes 02 (1) 288P WFC3/UVIS 1 29-Jul-2016 15:42:52.0 yes 03 (1) 288P WFC3/UVIS 1 29-Jul-2016 15:42:53.0 yes 04 (1) 288P WFC3/UVIS 1 29-Jul-2016 15:42:54.0 yes 05 (1) 288P WFC3/UVIS 1 29-Jul-2016 15:42:54.0 yes 5 Total Orbits Used ABSTRACT We propose to study the suspected binary nature of active asteroid 288P/300163. We aim to confirm or disprove the existence of a binary nucleus, and - if confirmed - to measure the mutual orbital period and orbit orientation of the compoents, and their sizes. We request 5 orbits of WFC3 1 Proposal 14790 (STScI Edit Number: 0, Created: Friday, July 29, 2016 2:42:55 PM EST) - Overview imaging, spaced at intervals of 8-12 days. -

The Solar System

5 The Solar System R. Lynne Jones, Steven R. Chesley, Paul A. Abell, Michael E. Brown, Josef Durech,ˇ Yanga R. Fern´andez,Alan W. Harris, Matt J. Holman, Zeljkoˇ Ivezi´c,R. Jedicke, Mikko Kaasalainen, Nathan A. Kaib, Zoran Kneˇzevi´c,Andrea Milani, Alex Parker, Stephen T. Ridgway, David E. Trilling, Bojan Vrˇsnak LSST will provide huge advances in our knowledge of millions of astronomical objects “close to home’”– the small bodies in our Solar System. Previous studies of these small bodies have led to dramatic changes in our understanding of the process of planet formation and evolution, and the relationship between our Solar System and other systems. Beyond providing asteroid targets for space missions or igniting popular interest in observing a new comet or learning about a new distant icy dwarf planet, these small bodies also serve as large populations of “test particles,” recording the dynamical history of the giant planets, revealing the nature of the Solar System impactor population over time, and illustrating the size distributions of planetesimals, which were the building blocks of planets. In this chapter, a brief introduction to the different populations of small bodies in the Solar System (§ 5.1) is followed by a summary of the number of objects of each population that LSST is expected to find (§ 5.2). Some of the Solar System science that LSST will address is presented through the rest of the chapter, starting with the insights into planetary formation and evolution gained through the small body population orbital distributions (§ 5.3). The effects of collisional evolution in the Main Belt and Kuiper Belt are discussed in the next two sections, along with the implications for the determination of the size distribution in the Main Belt (§ 5.4) and possibilities for identifying wide binaries and understanding the environment in the early outer Solar System in § 5.5. -

Theoretical Orbits of Planets in Binary Star Systems 1

Theoretical Orbits of Planets in Binary Star Systems 1 Theoretical Orbits of Planets in Binary Star Systems S.Edgeworth 2001 Table of Contents 1: Introduction 2: Large external orbits 3: Small external orbits 4: Eccentric external orbits 5: Complex external orbits 6: Internal orbits 7: Conclusion Theoretical Orbits of Planets in Binary Star Systems 2 1: Introduction A binary star system consists of two stars which orbit around their joint centre of mass. A large proportion of stars belong to such systems. What sorts of orbits can planets have in a binary star system? To examine this question we use a computer program called a multi-body gravitational simulator. This enables us to create accurate simulations of binary star systems with planets, and to analyse how planets would really behave in this complex environment. Initially we examine the simplest type of binary star system, which satisfies these conditions:- 1. The two stars are of equal mass. 2, The two stars share a common circular orbit. 3. Planets orbit on the same plane as the stars. 4. Planets are of negligible mass. 5. There are no tidal effects. We use the following units:- One time unit = the orbital period of the star system. One distance unit = the distance between the two stars. We can classify possible planetary orbits into two types. A planet may have an internal orbit, which means that it orbits around just one of the two stars. Alternatively, a planet may have an external orbit, which means that its orbit takes it around both stars. Also a planet's orbit may be prograde (in the same direction as the stars' orbits ), or retrograde (in the opposite direction to the stars' orbits). -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

1 Rotation Periods of Binary Asteroids with Large Separations

Rotation Periods of Binary Asteroids with Large Separations – Confronting the Escaping Ejecta Binaries Model with Observations a,b,* b a D. Polishook , N. Brosch , D. Prialnik a Department of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. b The Wise Observatory and the School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. * Corresponding author: David Polishook, [email protected] Abstract Durda et al. (2004), using numerical models, suggested that binary asteroids with large separation, called Escaping Ejecta Binaries (EEBs), can be created by fragments ejected from a disruptive impact event. It is thought that six binary asteroids recently discovered might be EEBs because of the high separation between their components (~100 > a/Rp > ~20). However, the rotation periods of four out of the six objects measured by our group and others and presented here show that these suspected EEBs have fast rotation rates of 2.5 to 4 hours. Because of the small size of the components of these binary asteroids, linked with this fast spinning, we conclude that the rotational-fission mechanism, which is a result of the thermal YORP effect, is the most likely formation scenario. Moreover, scaling the YORP effect for these objects shows that its timescale is shorter than the estimated ages of the three relevant Hirayama families hosting these binary asteroids. Therefore, only the largest (D~19 km) suspected asteroid, (317) Roxane , could be, in fact, the only known EEB. In addition, our results confirm the triple nature of (3749) Balam by measuring mutual events on its lightcurve that match the orbital period of a nearby satellite in addition to its distant companion. -

Binary Asteroids and the Formation of Doublet Craters

ICARUS 124, 372±391 (1996) ARTICLE NO. 0215 Binary Asteroids and the Formation of Doublet Craters WILLIAM F. BOTTKE,JR. Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Mail Code 170-25, Pasadena, California 91125 E-mail: [email protected] AND H. JAY MELOSH Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 Received April 29, 1996; revised August 14, 1996 found we could duplicate the observed fraction of doublet cra- At least 10% (3 out of 28) of the largest known impact craters ters found on Earth, Venus, and Mars. Our results suggest on Earth and a similar fraction of all impact structures on that any search for asteroid satellites should place emphasis Venus are doublets (i.e., have a companion crater nearby), on km-sized Earth-crossing asteroids with short-rotation formed by the nearly simultaneous impact of objects of compa- periods. 1996 Academic Press, Inc. rable size. Mars also has doublet craters, though the fraction found there is smaller (2%). These craters are too large and too far separated to have been formed by the tidal disruption 1. INTRODUCTION of an asteroid prior to impact, or from asteroid fragments dispersed by aerodynamic forces during entry. We propose that Two commonly held paradigms about asteroids and some fast rotating rubble-pile asteroids (e.g., 4769 Castalia), comets are that (a) they are composed of non-fragmented after experiencing a close approach with a planet, undergo tidal chunks of rock or rock/ice mixtures, and (b) they are soli- breakup and split into multiple co-orbiting fragments. -

1 on the Origin of the Pluto System Robin M. Canup Southwest Research Institute Kaitlin M. Kratter University of Arizona Marc Ne

On the Origin of the Pluto System Robin M. Canup Southwest Research Institute Kaitlin M. Kratter University of Arizona Marc Neveu NASA Goddard Space Flight Center / University of Maryland The goal of this chapter is to review hypotheses for the origin of the Pluto system in light of observational constraints that have been considerably refined over the 85-year interval between the discovery of Pluto and its exploration by spacecraft. We focus on the giant impact hypothesis currently understood as the likeliest origin for the Pluto-Charon binary, and devote particular attention to new models of planet formation and migration in the outer Solar System. We discuss the origins conundrum posed by the system’s four small moons. We also elaborate on implications of these scenarios for the dynamical environment of the early transneptunian disk, the likelihood of finding a Pluto collisional family, and the origin of other binary systems in the Kuiper belt. Finally, we highlight outstanding open issues regarding the origin of the Pluto system and suggest areas of future progress. 1. INTRODUCTION For six decades following its discovery, Pluto was the only known Sun-orbiting world in the dynamical vicinity of Neptune. An early origin concept postulated that Neptune originally had two large moons – Pluto and Neptune’s current moon, Triton – and that a dynamical event had both reversed the sense of Triton’s orbit relative to Neptune’s rotation and ejected Pluto onto its current heliocentric orbit (Lyttleton, 1936). This scenario remained in contention following the discovery of Charon, as it was then established that Pluto’s mass was similar to that of a large giant planet moon (Christy and Harrington, 1978). -

![Arxiv:2012.04712V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 8 Dec 2020 Direct Evidence of the Presence of Planets (E.G., ALMA Part- Nership Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6029/arxiv-2012-04712v1-astro-ph-ep-8-dec-2020-direct-evidence-of-the-presence-of-planets-e-g-alma-part-nership-et-al-976029.webp)

Arxiv:2012.04712V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 8 Dec 2020 Direct Evidence of the Presence of Planets (E.G., ALMA Part- Nership Et Al

DRAFT VERSION DECEMBER 10, 2020 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX63 First detection of orbital motion for HD 106906 b: A wide-separation exoplanet on a Planet Nine-like orbit MEIJI M. NGUYEN,1 ROBERT J. DE ROSA,2 AND PAUL KALAS1, 3, 4 1Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 2European Southern Observatory, Alonso de Cordova´ 3107, Vitacura, Santiago, Chile 3SETI Institute, Carl Sagan Center, 189 Bernardo Ave., Mountain View, CA 94043, USA 4Institute of Astrophysics, FORTH, GR-71110 Heraklion, Greece (Received August 26, 2020; Revised October 8, 2020; Accepted October 10, 2020) Submitted to AJ ABSTRACT HD 106906 is a 15 Myr old short-period (49 days) spectroscopic binary that hosts a wide-separation (737 au) planetary-mass ( 11 M ) common proper motion companion, HD 106906 b. Additionally, a circumbinary ∼ Jup debris disk is resolved at optical and near-infrared wavelengths that exhibits a significant asymmetry at wide separations that may be driven by gravitational perturbations from the planet. In this study we present the first detection of orbital motion of HD 106906 b using Hubble Space Telescope images spanning a 14 yr period. We achieve high astrometric precision by cross-registering the locations of background stars with the Gaia astromet- ric catalog, providing the subpixel location of HD 106906 that is either saturated or obscured by coronagraphic optical elements. We measure a statistically significant 31:8 7:0 mas eastward motion of the planet between ± the two most constraining measurements taken in 2004 and 2017. This motion enables a measurement of the +27 +27 inclination between the orbit of the planet and the inner debris disk of either 36 14 deg or 44 14 deg, depending on the true orientation of the orbit of the planet. -

Aas 14-267 Design of End-To-End Trojan Asteroid

AAS 14-267 DESIGN OF END-TO-END TROJAN ASTEROID RENDEZVOUS TOURS INCORPORATING POTENTIAL SCIENTIFIC VALUE Jeffrey Stuart,∗ Kathleen Howell,y and Roby Wilsonz The Sun-Jupiter Trojan asteroids are celestial bodies of great scientific interest as well as potential natural assets offering mineral resources for long-term human exploration of the solar system. Previous investigations have addressed the auto- mated design of tours within the asteroid swarm and the transition of prospective tours to higher-fidelity, end-to-end trajectories. The current development incorpo- rates the route-finding Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) algorithm into the auto- mated tour generation procedure. Furthermore, the potential scientific merit of the target asteroids is incorporated such that encounters with higher value asteroids are preferentially incorporated during sequence creation. INTRODUCTION Near Earth Objects (NEOs) are currently under consideration for manned sample return mis- sions,1 while a recent NASA feasibility assessment concludes that a mission to the Trojan asteroids can be accomplished at a projected cost of less than $900M in fiscal year 2015 dollars.2 Tour concepts within asteroid swarms allow for a broad sampling of interesting target bodies either for scientific investigation or as potential resources to support deep-space human missions. However, the multitude of asteroids within the swarms necessitates the use of automated design algorithms if a large number of potential mission options are to be surveyed. Previously, a process to automatically and rapidly generate sample tours within the Sun-Jupiter L4 Trojan asteroid swarm with a mini- mum of human interaction has been developed.3 This scheme also enables the automated transition of tours of interest into fully optimized, end-to-end trajectories using a variety of electrical power sources.4,5 This investigation extends the automated algorithm to use ant colony optimization, a heuristic search algorithm, while simultaneously incorporating a relative ‘scientific importance’ ranking into tour construction and analysis. -

Why Pluto Is Not a Planet Anymore Or How Astronomical Objects Get Named

3 Why Pluto Is Not a Planet Anymore or How Astronomical Objects Get Named Sethanne Howard USNO retired Abstract Everywhere I go people ask me why Pluto was kicked out of the Solar System. Poor Pluto, 76 years a planet and then summarily dismissed. The answer is not too complicated. It starts with the question how are astronomical objects named or classified; asks who is responsible for this; and ends with international treaties. Ultimately we learn that it makes sense to demote Pluto. Catalogs and Names WHO IS RESPONSIBLE for naming and classifying astronomical objects? The answer varies slightly with the object, and history plays an important part. Let us start with the stars. Most of the bright stars visible to the naked eye were named centuries ago. They generally have kept their old- fashioned names. Betelgeuse is just such an example. It is the eighth brightest star in the northern sky. The star’s name is thought to be derived ,”Yad al-Jauzā' meaning “the Hand of al-Jauzā يد الجوزاء from the Arabic i.e., Orion, with mistransliteration into Medieval Latin leading to the first character y being misread as a b. Betelgeuse is its historical name. The star is also known by its Bayer designation − ∝ Orionis. A Bayeri designation is a stellar designation in which a specific star is identified by a Greek letter followed by the genitive form of its parent constellation’s Latin name. The original list of Bayer designations contained 1,564 stars. The Bayer designation typically assigns the letter alpha to the brightest star in the constellation and moves through the Greek alphabet, with each letter representing the next fainter star. -

Chapter 5 Galaxies and Star Systems

Chapter 5 Galaxies and Star Systems Section 5.1 Galaxies Terms: • Galaxy • Spiral Galaxy • Elliptical Galaxy • Irregular Galaxy • Milky Way Galaxy • Quasar • Black Hole Types of Galaxies A galaxy is a huge group of single stars, star systems, star clusters, dust, and gas bound together by gravity. There are billions of galaxies in the universe. The largest galaxies have more than a trillion stars! Astronomers classify most galaxies into the following types: spiral, elliptical, and irregular. Spiral galaxies are those that appear to have a bulge in the middle and arms that spiral outward, like pinwheels. The spiral arms contain many bright, young stars as well as gas and dust. Most new stars in the spiral galaxies form in theses spiral arms. Relatively few new stars form in the central bulge. Some spiral galaxies, called barred-spiral galaxies, have a huge bar-shaped region of stars and gas that passes through their center. Not all galaxies have spiral arms. Elliptical galaxies look like round or flattened balls. These galaxies contain billions of the stars but have little gas and dust between the stars. Because there is little gas or dust, stars are no longer forming. Most elliptical galaxies contain only old stars. Some galaxies do not have regular shapes, thus they are called irregular galaxies. These galaxies are typically smaller than other types of galaxies and generally have many bright, young stars. They contain a lot of gas a dust to from new stars. The Milky Way Galaxy Although it is difficult to know what the shape of the Milky Way Galaxy is because we are inside of it, astronomers have identified it as a typical spiral galaxy.