1 on the Origin of the Pluto System Robin M. Canup Southwest Research Institute Kaitlin M. Kratter University of Arizona Marc Ne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formation of TRAPPIST-1

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 11, EPSC2017-265, 2017 European Planetary Science Congress 2017 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2017 Formation of TRAPPIST-1 C.W Ormel, B. Liu and D. Schoonenberg University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands ([email protected]) Abstract start to drift by aerodynamical drag. However, this growth+drift occurs in an inside-out fashion, which We present a model for the formation of the recently- does not result in strong particle pileups needed to discovered TRAPPIST-1 planetary system. In our sce- trigger planetesimal formation by, e.g., the streaming nario planets form in the interior regions, by accre- instability [3]. (a) We propose that the H2O iceline (r 0.1 au for TRAPPIST-1) is the place where tion of mm to cm-size particles (pebbles) that drifted ice ≈ the local solids-to-gas ratio can reach 1, either by from the outer disk. This scenario has several ad- ∼ vantages: it connects to the observation that disks are condensation of the vapor [9] or by pileup of ice-free made up of pebbles, it is efficient, it explains why the (silicate) grains [2, 8]. Under these conditions plan- TRAPPIST-1 planets are Earth mass, and it provides etary embryos can form. (b) Due to type I migration, ∼ a rationale for the system’s architecture. embryos cross the iceline and enter the ice-free region. (c) There, silicate pebbles are smaller because of col- lisional fragmentation. Nevertheless, pebble accretion 1. Introduction remains efficient and growth is fast [6]. (d) At approx- TRAPPIST-1 is an M8 main-sequence star located at a imately Earth masses embryos reach their pebble iso- distance of 12 pc. -

News Feature: the Mars Anomaly

NEWS FEATURE NEWS FEATURE The Mars anomaly The red planet’s size is at the heart of a rift of ideas among researchers modeling the solar system’s formation. Stephen Ornes, Science Writer The presence of water isn’t the only Mars mystery sci- debate, data, and computer simulations, until re- entists are keen to probe. Another centers around a cently most models predicted that Mars should be seemingly trivial characteristic of the Red Planet: its many times its observed size. Getting Mars to form size. Classic models of solar system formation predict attherightplacewiththerightsizeisacrucialpartof that the girth of rocky worlds should grow with their any coherent explanation of the solar system’sevo- distance from the sun. Venus and Earth, for example, lution from a disk of gas and dust to its current con- should exceed Mercury, which they do. Mars should at figuration. In trying to do so, researchers have been — least match Earth, which it doesn’t. The diameter of the forced to devise models that are more detailed and — RedPlanetislittlemorethanhalfthatofEarth(1,2). even wilder than any seen before. “We still don’t understand why Mars is so small,” Nebulous Notions says astronomer Anders Johansen, who builds com- The solar system began as an immense cloud of dust putational models of planet formation at Lund Univer- and gas called a nebula. The idea of a nebular origin sity in Sweden. “It’s a really compelling question that dates back nearly 300 years. In 1734, Swedish scientist drives a lot of new theories.” and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg—whoalsoclaimed Understanding the planet’s diminutive size is key that Martian spirits had communed with him—posited to knowing how the entire solar system formed. -

OCEANOGRAPHY an Additional 1.4 Tg of Carbon Per Year Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations from Ice Loss and Ocean Life Over This Period

research highlights OCEANOGRAPHY an additional 1.4 Tg of carbon per year atmospheric CO2 concentrations from Ice loss and ocean life over this period. A rise in phytoplankton Antarctic ice cores. They found that Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles http://doi.org/p27 (2013) productivity in the surface waters of the two younger periods of enhanced the Laptev, East Siberian, Chukchi and mixing coincided with a steep increase in Beaufort seas was responsible for the atmospheric CO2 levels, and the oldest with increase in carbon uptake. In contrast, net a small, temporary rise. carbon uptake declined in the Barents Sea, The team concluded that enhanced where a warming-induced outgassing of vertical mixing in these intervals brought surface-water CO2 countered the rise in CO2-rich waters from the deep ocean to the primary production. surface, allowing CO2 to escape from these The findings suggest that the continued upwelled waters to the atmosphere. AN decline of Arctic sea ice cover could be accompanied by a rise in the oceanic uptake PLANETARY SCIENCE of carbon dioxide, although uncertainties Weighing Phobos in the response of physical, chemical and Icarus http://doi.org/p26 (2013) biological processes to sea ice loss hinder reliable predictions at this stage. AA PALAEOCEANOGRAPHY Southern upwelling Nature Commun. 4, 2758 (2013). At the end of the last glacial period about 20,000 years ago, atmospheric CO2 concentrations rose in several steps. Radiocarbon measurements from a marine sediment core suggest that the upwelling of © FRANS LANTING STUDIO / ALAMY © FRANS LANTING STUDIO carbon-rich waters in the Southern Ocean contributed to the CO2 rise. -

Constructing the Secular Architecture of the Solar System I: the Giant Planets

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. secular c ESO 2018 May 29, 2018 Constructing the secular architecture of the solar system I: The giant planets A. Morbidelli1, R. Brasser1, K. Tsiganis2, R. Gomes3, and H. F. Levison4 1 Dep. Cassiopee, University of Nice - Sophia Antipolis, CNRS, Observatoire de la Cˆote d’Azur; Nice, France 2 Department of Physics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki; Thessaloniki, Greece 3 Observat´orio Nacional; Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil 4 Southwest Research Institute; Boulder, CO, USA submitted: 13 July 2009; accepted: 31 August 2009 ABSTRACT Using numerical simulations, we show that smooth migration of the giant planets through a planetesimal disk leads to an orbital architecture that is inconsistent with the current one: the resulting eccentricities and inclinations of their orbits are too small. The crossing of mutual mean motion resonances by the planets would excite their orbital eccentricities but not their orbital inclinations. Moreover, the amplitudes of the eigenmodes characterising the current secular evolution of the eccentricities of Jupiter and Saturn would not be reproduced correctly; only one eigenmode is excited by resonance-crossing. We show that, at the very least, encounters between Saturn and one of the ice giants (Uranus or Neptune) need to have occurred, in order to reproduce the current secular properties of the giant planets, in particular the amplitude of the two strongest eigenmodes in the eccentricities of Jupiter and Saturn. Key words. Solar System: formation 1. Introduction Snellgrove (2001). The top panel shows the evolution of the semi major axes, where Saturn’ semi-major axis is depicted The formation and evolution of the solar system is a longstand- by the upper curve and that of Jupiter is the lower trajectory. -

Spin-Orbit Coupling for Close-In Planets Alexandre C

A&A 630, A102 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936336 & © ESO 2019 Astrophysics Spin-orbit coupling for close-in planets Alexandre C. M. Correia1,2 and Jean-Baptiste Delisle2,3 1 CFisUC, Department of Physics, University of Coimbra, 3004-516 Coimbra, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] 2 ASD, IMCCE, Observatoire de Paris, PSL Université, 77 Av. Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris, France 3 Observatoire de l’Université de Genève, 51 chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland Received 17 July 2019 / Accepted 20 August 2019 ABSTRACT We study the spin evolution of close-in planets in multi-body systems and present a very general formulation of the spin-orbit problem. This includes a simple way to probe the spin dynamics from the orbital perturbations, a new method for computing forced librations and tidal deformation, and general expressions for the tidal torque and capture probabilities in resonance. We show that planet–planet perturbations can drive the spin of Earth-size planets into asynchronous or chaotic states, even for nearly circular orbits. We apply our results to Mercury and to the KOI-1599 system of two super-Earths in a 3/2 mean motion resonance. Key words. celestial mechanics – planets and satellites: general – chaos 1. Introduction resonant rotation with the orbital libration frequency (Correia & Robutel 2013; Leleu et al. 2016; Delisle et al. 2017). The inner planets of the solar system, like the majority of the Despite the proximity of solar system bodies, the determi- main satellites, currently present a rotation state that is differ- nation of their rotational periods has only been achieved in ent from what is believed to have been the initial state (e.g., the second half of the 20th century. -

Protoplanetary Disk Turbulence Driven by the Streaming Instability: Non-Linear Saturation and Particle Concentration

Accepted for publication in ApJ A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 02/07/07 PROTOPLANETARY DISK TURBULENCE DRIVEN BY THE STREAMING INSTABILITY: NON-LINEAR SATURATION AND PARTICLE CONCENTRATION A. Johansen1 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Astronomie, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany and A. Youdin2 Princeton University Observatory, Princeton, NJ 08544 Accepted for publication in ApJ ABSTRACT We present simulations of the non-linear evolution of streaming instabilities in protoplanetary disks. The two components of the disk, gas treated with grid hydrodynamics and solids treated as super- particles, are mutually coupled by drag forces. We find that the initially laminar equilibrium flow spontaneously develops into turbulence in our unstratified local model. Marginally coupled solids (that couple to the gas on a Keplerian time-scale) trigger an upward cascade to large particle clumps with peak overdensities above 100. The clumps evolve dynamically by losing material downstream to the radial drift flow while receiving recycled material from upstream. Smaller, more tightly coupled solids produce weaker turbulence with more transient overdensities on smaller length scales. The net inward radial drift is decreased for marginally coupled particles, whereas the tightly coupled particles migrate faster in the saturated turbulent state. The turbulent diffusion of solid particles, measured by their random walk, depends strongly on their stopping time and on the solids-to-gas ratio of the background state, but diffusion is generally modest, particularly for tightly coupled solids. Angular momentum transport is too weak and of the wrong sign to influence stellar accretion. Self-gravity and collisions will be needed to determine the relevance of particle overdensities for planetesimal formation. -

Setting the Stage: Planet Formation and Volatile Delivery

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Setting the Stage: Planet formation and Volatile Delivery Julia Venturini1 · Maria Paula Ronco2;3 · Octavio Miguel Guilera4;2;3 Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract The diversity in mass and composition of planetary atmospheres stems from the different building blocks present in protoplanetary discs and from the different physical and chemical processes that these experience during the planetary assembly and evolution. This review aims to summarise, in a nutshell, the key concepts and processes operating during planet formation, with a focus on the delivery of volatiles to the inner regions of the planetary system. 1 Protoplanetary discs: the birthplaces of planets Planets are formed as a byproduct of star formation. In star forming regions like the Orion Nebula or the Taurus Molecular Cloud, many discs are observed around young stars (Isella et al, 2009; Andrews et al, 2010, 2018a; Cieza et al, 2019). Discs form around new born stars as a natural consequence of the collapse of the molecular cloud, to conserve angular momentum. As in the interstellar medium, it is generally assumed that they contain typically 1% of their mass in the form of rocky or icy grains, known as dust; and 99% in the form of gas, which is basically H2 and He (see, e.g., Armitage, 2010). However, the dust-to-gas ratios are usually higher in discs (Ansdell et al, 2016). There is strong observational evidence supporting the fact that planets form within those discs (Bae et al, 2017; Dong et al, 2018; Teague et al, 2018; Pérez et al, 2019), which are accordingly called protoplanetary discs. -

Trans-Neptunian Objects a Brief History, Dynamical Structure, and Characteristics of Its Inhabitants

Trans-Neptunian Objects A Brief history, Dynamical Structure, and Characteristics of its Inhabitants John Stansberry Space Telescope Science Institute IAC Winter School 2016 IAC Winter School 2016 -- Kuiper Belt Overview -- J. Stansberry 1 The Solar System beyond Neptune: History • 1930: Pluto discovered – Photographic survey for Planet X • Directed by Percival Lowell (Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, Arizona) • Efforts from 1905 – 1929 were fruitless • discovered by Clyde Tombaugh, Feb. 1930 (33 cm refractor) – Survey continued into 1943 • Kuiper, or Edgeworth-Kuiper, Belt? – 1950’s: Pluto represented (K.E.), or had scattered (G.K.) a primordial, population of small bodies – thus KBOs or EKBOs – J. Fernandez (1980, MNRAS 192) did pretty clearly predict something similar to the trans-Neptunian belt of objects – Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs), trans-Neptunian region best? – See http://www2.ess.ucla.edu/~jewitt/kb/gerard.html IAC Winter School 2016 -- Kuiper Belt Overview -- J. Stansberry 2 The Solar System beyond Neptune: History • 1978: Pluto’s moon, Charon, discovered – Photographic astrometry survey • 61” (155 cm) reflector • James Christy (Naval Observatory, Flagstaff) – Technologically, discovery was possible decades earlier • Saturation of Pluto images masked the presence of Charon • 1988: Discovery of Pluto’s atmosphere – Stellar occultation • Kuiper airborne observatory (KAO: 90 cm) + 7 sites • Measured atmospheric refractivity vs. height • Spectroscopy suggested N2 would dominate P(z), T(z) • 1992: Pluto’s orbit explained • Outward migration by Neptune results in capture into 3:2 resonance • Pluto’s inclination implies Neptune migrated outward ~5 AU IAC Winter School 2016 -- Kuiper Belt Overview -- J. Stansberry 3 The Solar System beyond Neptune: History • 1992: Discovery of 2nd TNO • 1976 – 92: Multiple dedicated surveys for small (mV > 20) TNOs • Fall 1992: Jewitt and Luu discover 1992 QB1 – Orbit confirmed as ~circular, trans-Neptunian in 1993 • 1993 – 4: 5 more TNOs discovered • c. -

New Horizons Pluto/KBO Mission Impact Hazard

New Horizons Pluto/KBO Mission Impact Hazard Hal Weaver NH Project Scientist The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Outline • Background on New Horizons mission • Description of Impact Hazard problem • Impact Hazard mitigation – Hubble Space Telescope plays a key role New Horizons: To Pluto and Beyond The Initial Reconnaissance of The Solar System’s “Third Zone” KBOs Pluto-Charon Jupiter System 2016-2020 July 2015 Feb-March 2007 Launch Jan 2006 PI: Alan Stern (SwRI) PM: JHU Applied Physics Lab New Horizons is NASA’s first New Frontiers Mission Frontier of Planetary Science Explore a whole new region of the Solar System we didn’t even know existed until the 1990s Pluto is no longer an outlier! Pluto System is prototype of KBOs New Horizons gives the first close-up view of these newly discovered worlds New Horizons Now (overhead view) NH Spacecraft & Instruments 2.1 meters Science Team: PI: Alan Stern Fran Bagenal Rick Binzel Bonnie Buratti Andy Cheng Dale Cruikshank Randy Gladstone Will Grundy Dave Hinson Mihaly Horanyi Don Jennings Ivan Linscott Jeff Moore Dave McComas Bill McKinnon Ralph McNutt Scott Murchie Cathy Olkin Carolyn Porco Harold Reitsema Dennis Reuter Dave Slater John Spencer Darrell Strobel Mike Summers Len Tyler Hal Weaver Leslie Young Pluto System Science Goals Specified by NASA or Added by New Horizons New Horizons Resolution on Pluto (Simulations of MVIC context imaging vs LORRI high-resolution "noodles”) 0.1 km/pix The Best We Can Do Now 0.6 km/pix HST/ACS-PC: 540 km/pix New Horizons Science Status • -

A Deep Search for Additional Satellites Around the Dwarf Planet

Search for Additional Satellites around Haumea A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 01/23/15 A DEEP SEARCH FOR ADDITIONAL SATELLITES AROUND THE DWARF PLANET HAUMEA Luke D. Burkhart1,2, Darin Ragozzine1,3,4, Michael E. Brown5 Search for Additional Satellites around Haumea ABSTRACT Haumea is a dwarf planet with two known satellites, an unusually high spin rate, and a large collisional family, making it one of the most interesting objects in the outer solar system. A fully self-consistent formation scenario responsible for the satellite and family formation is still elusive, but some processes predict the initial formation of many small moons, similar to the small moons recently discovered around Pluto. Deep searches for regular satellites around KBOs are difficult due to observational limitations, but Haumea is one of the few for which sufficient data exist. We analyze Hubble Space Telescope (HST) observations, focusing on a ten-consecutive-orbit sequence obtained in July 2010, to search for new very small satellites. To maximize the search depth, we implement and validate a non-linear shift-and-stack method. No additional satellites of Haumea are found, but by implanting and recovering artificial sources, we characterize our sensitivity. At distances between 10,000 km and 350,000 km from Haumea, satellites with radii as small as 10 km are ruled out, assuming∼ an albedo∼ (p 0.7) similar to Haumea. We also rule out satellites larger∼ than &40 km in most of the Hill sphere using≃ other HST data. This search method rules out objects similar in size to the small moons of Pluto. -

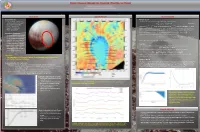

Motivation Sputnik Planitia Flexural Modeling Plans for GEOL

Motivation Sputnik Planitia Flexural modeling Sputnik Planitia Flexure model • Large teardrop-shaped basin The flexure of an elastic plate in two dimensions obeys Equation 1 located on Pluto at 20°N 180°E 푑4푤 퐷 + 푚 − 푐 푔푤 = 푉0 Equation 1. • Size: 1300 km by 900 km 푑푥4 4퐷 1/4 퐸∗ℎ3 • Depth: 3-4 km (basin) where 훼 = is the flexural parameter, 퐷 = is the flexural rigidity, is the 휌 −휌 12(1−푣2) 푚 • 푚 푐 Deposit of nitrogen ice density of the underlying layer of the ice shell, is the density of the ice shell. g is the gravity on • 푐 Water ice basement Pluto, E is the Young’s modulus of water ice, h is the elastic thickness, and 휈 is Poisson’s ratio 푑3푤 1 푑푤 For a single vertical load at 푥 = 0 , the boundary conditions are 퐷 = 푉 and = 0 Formation Hypotheses 푑푥3 2 0 푑푥 • An ancient impact basin created The deflection due to several line loads is found by superposition: 푉 훼3 푥−푥 푥−푥 푥−푥 by an impactor later filled with 푤 = σ 푖 sin 푖 + cos 푖 exp − 푖 Equation 2. 푖 8퐷 훼 훼 훼 N2 ice. The feature would have moved to the current location Where {푉푖} is the magnitude of the loads at position {푥푖} through polar wander. • Runaway deposition of N2 ice Inversion due to albedo feedback at the The load vector 퐕 that produces topography 퐰, is found by least squares optimization: ±30°. The depression is due to 퐕 = 퐌′퐌 + 퐂 −1 퐌′퐰 elastic flexure under the load of 풎 where M is the operator matrix that links a load at position 푥푗 to deflection at a point 푥푖 a thick N2 ice cap. -

THE EARTH's GRAVITY OUTLINE the Earth's Gravitational Field

GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) THE EARTH'S GRAVITY OUTLINE The Earth's gravitational field 2 Newton's law of gravitation: Fgrav = GMm=r ; Gravitational field = gravitational acceleration g; gravitational potential, equipotential surfaces. g for a non–rotating spherically symmetric Earth; Effects of rotation and ellipticity – variation with latitude, the reference ellipsoid and International Gravity Formula; Effects of elevation and topography, intervening rock, density inhomogeneities, tides. The geoid: equipotential mean–sea–level surface on which g = IGF value. Gravity surveys Measurement: gravity units, gravimeters, survey procedures; the geoid; satellite altimetry. Gravity corrections – latitude, elevation, Bouguer, terrain, drift; Interpretation of gravity anomalies: regional–residual separation; regional variations and deep (crust, mantle) structure; local variations and shallow density anomalies; Examples of Bouguer gravity anomalies. Isostasy Mechanism: level of compensation; Pratt and Airy models; mountain roots; Isostasy and free–air gravity, examples of isostatic balance and isostatic anomalies. Background reading: Fowler §5.1–5.6; Lowrie §2.2–2.6; Kearey & Vine §2.11. GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) THE EARTH'S GRAVITY FIELD Newton's law of gravitation is: ¯ GMm F = r2 11 2 2 1 3 2 where the Gravitational Constant G = 6:673 10− Nm kg− (kg− m s− ). ¢ The field strength of the Earth's gravitational field is defined as the gravitational force acting on unit mass. From Newton's third¯ law of mechanics, F = ma, it follows that gravitational force per unit mass = gravitational acceleration g. g is approximately 9:8m/s2 at the surface of the Earth. A related concept is gravitational potential: the gravitational potential V at a point P is the work done against gravity in ¯ P bringing unit mass from infinity to P.