RECENT LITERATURE Edited by John A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tackling Indian Mynas

The Myna Problem = a Major Issue Bill Handke OAM Canberra Indian Myna Action Group Inc Julian Robinson Indian (Common) Myna Sturnus tristis • Native to Indian sub-continent – distinctive colouring and call – aggressive / territorial • but roost communally – opportunistic feeder : omnivorous – long lived – breeds Oct – March • up to 3 clutches of 6-8 chicks ❖ adaptive, intelligent, highly invasive • Not to be confused with the Noisy Miner – native – nectar feeder – protective of food source – becoming more common in Canberra urban fringe – can cause some environmental problems (just like the Bell Miner) The Myna Invasion • Introduced Melbourne 1862 – to control locusts in market gardens • Taken to Sydney in early 1880s • Taken to Qld canefields (1883) – to control cane beetle • same as for cane toad • Introduced Canberra in 1968 – 250 per km2 • Now across eastern seaboard – densities ↑ 750-1250 km2 Testimonials • Among 100 most invasive species worldwide – (IUCN 2000) • Voted most hated pest in Aust – ABC Wild Watch Quest for Pests 2005 • beat cane toad, feral cat and fox • Most Extreme Threat Category – Bureau Rural Science / Dept Environment & Water • “You can have native birds or Indian Mynas — but not both” Mat & Cathy Gilfedder – Ian Fraser, local naturalist & 2006 Winner Aust Natural History Medallion The International Experience • Mynas have lead to the demise / decline of: – Mangaia Kingfisher (Cook Is) – Red-moustached Fruit Dove (French Polynesia) – Seychelles Magpie Robin (Seychelles) – Echo Parakeet (Mauritius) – Tui, NZ Pigeon -

Preliminary Systematic Notes on Some Old World Passerines

Kiv. ital. Orn., Milano, 59 (3-4): 183-195, 15-XII-1989 STOBRS L. OLSON PRELIMINARY SYSTEMATIC NOTES ON SOME OLD WORLD PASSERINES TIPOGKAFIA FUSI - PAVIA 1989 Riv. ital. Ora., Milano, 59 (3-4): 183-195, 15-XII-1989 STORRS L. OLSON (*) PRELIMINARY SYSTEMATIC NOTES ON SOME OLD WORLD PASSERINES Abstract. — The relationships of various genera of Old World passerines are assessed based on osteological characters of the nostril and on morphology of the syrinx. Chloropsis belongs in the Pycnonotidae. Nicator is not a bulbul and is returned to the Malaconotidae. Neolestes is probably not a bulbul. The Malagasy species placed in the genus Phyllastrephus are not bulbuls and are returned to the Timaliidae. It is confirmed that the relationships of Paramythia, Oreocharis, Malia, Tylas, Hyper - gerus, Apalopteron, and Lioptilornis (Kupeornis) are not with the Pycnonotidae. Trochocercus nitens and T. cycmomelas are monarchine flycatchers referable to the genus TerpsiphoTie. « Trochocercus s> nigromitratus, « T. s> albiventer, and « T. » albo- notatus are tentatively referred to Elminia. Neither Elminia nor Erythrocercus are monarch] nes and must be removed from the Myiagridae (Monarchidae auct.). Grai- lina and Aegithina- are monarch flycatchers referable to the Myiagridae. Eurocephalus belongs in the Laniinae, not the Prionopinae. Myioparus plumbeus is confirmed as belonging in the Muscicapidae. Pinarornis lacks the turdine condition of the syrinx. It appears to be most closely related to Neoeossypha, Stizorhina, and Modulatrix, and these four genera are placed along with Myadestes in a subfamily Myadestinae that is the primitive sister-group of the remainder of the Muscicapidae, all of which have a derived morphology of the syrinx. -

Island Monarch Monarcha Cinerascens on Ashmore Reef: First Records for Australian Territory

150 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2011, 28, 150–161 Island Monarch Monarcha cinerascens on Ashmore Reef: First Records for Australian Territory MIKE CARTER1, ROHAN H. CLARKE2 and GEORGE SWANN3 130 Canadian Bay Road, Mt Eliza, Victoria 3930 (Email: [email protected]) 2School of Biological Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3800 3Kimberley Birdwatching, P.O. Box 220, Broome, Western Australia 6725 Summary Island Monarchs Monarcha cinerascens were observed at Ashmore Reef during the months of October and/or November in 2004, 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010. In 2010 up to four were present together, and we consider that more than six individuals visited the Reef that year. Only single birds were observed on previous occasions. Thus the total number of Island Monarchs that has been detected on the Reef is at least eight and probably greater than ten. Reports of the 2004, 2007, 2008 and 2009 observations were assessed and accepted by the Birds Australia Rarities Committee (Case nos 467, 544, 581 and 701, respectively), with the 2004 observation being the first record for Australian territory. This paper documents all known occurrences on Ashmore Reef. We postulate that these occurrences are examples of dispersal of birds seeking suitable habitat beyond their usual range in the islands of the Indonesian archipelago just to the north. Introduction Ashmore Reef is an External Australian Territory located in Commonwealth waters within the Australian Economic Exclusion Zone. In 1983 it was declared a National Nature Reserve by the Australian Nature Conservation Agency, and continues to be administered by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population & Communities as a National Nature Reserve. -

CLASSIDCATION of SOME BIRD COMMUNITIES in CHIANG Mal PROVINCE, NORTHERN THAILAND

NAT. HIST. BULL. SIAM Soc. 33(2) : 121-138, 1985. CLASSIDCATION OF SOME BIRD COMMUNITIES IN CHIANG MAl PROVINCE, NORTHERN THAILAND Ookeow Prakobvitayakit Beaver* and Narlt Srltasuwan* ABSTRACT This study examines the bird commuirities of the mountain areas in Chiang Mai Province, northern Thailand, using presence-absence distribution data. The richest community (143 species) was found in submontane evergreen broad leaved forest on Doi Inthanon at 1600 m. The summit area (2590 m) supported fewer species than did areas of drier, lower elevation forest on Doi Pui-Suthep, from 300 to 1685 m. It is suggested that bird species diversity could be interpreted primarily in terms of vegetational complexity. Limited habitat disturbance may enhance diversity through creating artificial edge habitats and clearings. INTRODUCTION Thai ornithologists have only in recent years paid attention to the ecological aspects of avifaunas. Logging, burning, and shifting cultivation not only cause the ecological problems of erosion and rapid water runoff but also are endangering many native species of the flora and fauna through destruction of their natural habitats. Chiang Mai is one of the best areas in Thailand for bird watching but it is also one of the areas experiencing most serious modification by man. An under standing the distribution of birds in various environmental situations may lead to better methods of park or habitat management. In this paper we. describe the structure of several habitat types and report on the distribution of birds in them. The following questions are also considered: 1. How much variation exists and what factors control species richness in the selected study are~? 2. -

Research Article Birds of Rawanwadi Region Bhandara, Central India

Volume 5, No 2/2018 ISSN 2313-0008 (Print); ISSN 2313-0016 (Online) Research Article Malays. j. med. biol. res. Birds of Rawanwadi Region Bhandara, Central India Kishor G. Patil1, Deeksha Dabrase2, Virendra A. Shende3* 1,2Department of Zoology, Institute of Science, R. T. Road, Nagpur (M.S.), INDIA 3K. Z. S. Science College, Bramhani-Kalmeshwar, Dist- Nagpur (M.S.), INDIA *Email for Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT The region of Rawanwadi reservoir is a good habitat for insects, fishes, reptiles as well as birds. Its geographical location is 21.043197 N, 79.729924 E. Observations were done by two visits on every month from May 2015 to April 2016 in the morning and evening hours. Bird observation and recording were done with the help of binocular and digital cameras. Total 143 species of birds were recorded belonging to 15 orders and 41 families. Out of total 143 species 07 are migrant, 95 are Resident and 41 are Resident migrant. Seasonal variation is well marked in birds due to availability of food and nesting and suitable environmental conditions. Largest number (60) of bird species is recorded from order Passeriformes which belonging to 17 families. Key words: Rawanwadi reservoir, Biodiversity, Birds 10/13/2018 Source of Support: None, No Conflict of Interest: Declared This article is is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon work non-commercially, and although the new works must also acknowledge and be non-commercial. INTRODUCTION Birds are described as a ‘Feathered Biped’. -

The Threatened and Near-Threatened Birds of Luzon, Philippines, and the Role of the Sierra Madre Mountains in Their Conservation

Bird Conservation International (1995) 5:79-115 The threatened and near-threatened birds of Luzon, Philippines, and the role of the Sierra Madre mountains in their conservation MICHAEL K0IE POULSEN Summary Fieldwork on the distribution, status and ecology of birds was conducted in the northern Sierra Madre mountain range, Luzon, Philippines, during March-May 1991 and March- May 1992. The findings show the area to be one of the most important for conservation of threatened species of birds in all Asia. The results are here combined with evidence from earlier surveys by other searchers. Fourteen threatened and 18 near-threatened species are now known from the area. This paper reports on all the threatened and near-threatened resident species of the island of Luzon, with special emphasis on their occurrence in the Sierra Madre mountains. In addition, the paper treats species with very limited global distribution that breed in Luzon, and lists species of forest birds endemic to the Philippines that have not previously been reported from the Sierra Madre mountains. Maps show the known sites for 17 species of special concern for conservation. New data on the altitudinal distribution of threatened and near-threatened species sug- gest that it is essential to protect primary forest at all elevations. Introduction No other Asian island has as many threatened species of bird as Luzon, closely followed by Mindanao, both in the Philippines. A total of 42 species listed as threatened or near-threatened by Collar and Andrew (1988) are known from Luzon including 15 breeding species listed as threatened. The vast majority of species of special concern to conservation (threatened, near- threatened and restricted-range) depend on forested habitats. -

Avifauna of Thrissur District, Kerala, India

CATALOGUE ZOOS' PRINT JOURNAL 20(2): 1774-1783 AVIFAUNA OF THRISSUR DISTRICT, KERALA, INDIA E.A. Jayson 1 and C. Sivaperuman 2 Division of Forest Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, Kerala Forest Research Institute, Peechi, Thrissur, Kerala 680653, India Email: 1 [email protected]; 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT is situated in the central region and is in the western slope of Three hundred and thirteen taxa of birds belonging to 64 the southern Western Ghats (Figure 1). The extent of the area Families were recorded in the Thrissur district, Kerala during is 1,041km2. The forests of Thrissur district fall within three a study on the avifauna there carried out from 1992 to 2002. 219 species of these were residents, 68 were trans- administrative divisions of the Kerala Forest and Wildlife continental migrants, 26 were local migrants and one species Department, viz. Thrissur, Chalakkudi and Vazhachal. Two was a straggler. The Order Passeriformes was highest in wildlife sanctuaries, namely the Peechi-Vazhani and the dominance followed by Charadriiformes, Ciconiiformes, Chimmony and a Ramsar site, the Vembanad-Kole wetlands Falconiformes, Coraciiformes and Piciformes. Seven exist in the district. species endemic to the Western Ghats and 11 species having threatened status were recorded. Out of the 1,340 species of birds recorded from the Indian subcontinent, Topographically, the area is divisible into the Machad Mala 23% were found in Thrissur district. This is the first attempt Ridge, the Vellani Mala Ridge, the low-lying foothills of the to compile district-wise distribution of avifauna in Kerala, Machad Mala Ridge, the Vellani Mala Ridge, the Anaikkal- which will pave way for a Bird Atlas of Kerala. -

The Systematic Affinity of the Enigmatic Lamprolia Victoriae (Aves

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 48 (2008) 1218–1222 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication The systematic affinity of the enigmatic Lamprolia victoriae (Aves: Passeriformes)—An example of avian dispersal between New Guinea and Fiji over Miocene intermittent land bridges? Martin Irestedt a,*, Jérôme Fuchs b,c, Knud A. Jønsson d, Jan I. Ohlson e, Eric Pasquet f,g, Per G.P. Ericson e a Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b University of Cape Town, Department of Zoology, Percy Fitzpatrick Institute of African Ornithology-DST-NRF Centre of Excellence, PD Hahn: 4.04, Rondebosch 7701, Cape Town, South Africa c Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, 3101 Valley Life Science Building, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3160, USA d Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark e Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden f UMR5202 ‘‘Origine, Structure et Evolution de la Biodiversité”, Département Systématique et Evolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 55 Rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France g Service Commun de Systématique Moléculaire, IFR CNRS 101, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 43, rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 1. Introduction In recent publications (e.g. Coates et al., 2006), Lamprolia is Lamprolia victoriae (silktail) is a distinctive bird endemic to placed among the monarch-flycatchers (Monarchidae). However, the Fiji Islands, where two well-marked subspecies inhabit hu- there is no morphological synapomorphy that unambiguously mid forest undergrowth and subcanopy on the islands of Taveuni groups Lamprolia with the monarchs, and several other passerine (L. -

Tinian Monarch Petition 0

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR Tinian Monarch (Monarcha takatsukasae) Photo by Eric VanderWerf, USFWS PETITION TO LIST THE TINIAN MONARCH (Monarcha takatsukasae) AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT December 11, 2013 CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Center Tinian Monarch Petition 0 Notice of Petition ________________________________________________________________________ Sally Jewell, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Dan Ashe, Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Douglas Krofta, Chief Branch of Listing, Endangered Species Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] PETITIONER The Center for Biological Diversity (“Center”) is a non-profit, public interest environmental organization dedicated to the protection of native species and their habitats through science, policy, and environmental law. The Center is supported by more than 625,000 members and activists. The Center and its members are concerned with the conservation of endangered species and the effective implementation of the Endangered Species Act. Center Tinian Monarch Petition 1 Submitted this 11th day of December, 2013 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b); Section 553(e) of the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e); and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Tara Easter, Tierra Curry, and Randy Harper hereby petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS,” “Service”), to list the Tinian monarch ((Monarcha takatsukasae) as a threatened or endangered species. -

MAMMALS Seen I Thailand and Cambodia Jan

BIRDS, M A M M A LS, A MPH IBI A NS and R EPT I L ES seen in Thailand and Sri Lanka Jan 15 ± Feb 9 2014 Stefan Lithner banteng Photo © Stefan Lithner Acknowledgements The result of this expedition I dedicate to my excellent guides: Mr Tu (Rattapon Kaichid) in Thailand and Mr Saman Weediyabandara in coorporation with Mr Malinda Ekanayake BAURS & Co Travel Ltd, Colombo Sri Lanka. I also acknowledge Mr Sampath de A Goonatilake, Programme Officer IUCN for confirming bats from my photos, and Mr Joakim Johansson, Örebro Sweden for confirming the lizards. To minimize errata I sent my typescript of this report to each of my two guides for comments or corrections on their part of the trip. I received no comments. 1(66) M APS These maps show approximate geographical position for the sites visited. Thailand Sites from north to south: Doi Lang (National Park situated on the Thai side of the border), Doi Inthanon, Huai Kha Kaeng. 2(66) Sri Lanka Sites from north to south, and from west to east: Kalpitiya, Kihtulgala, Sinharaja, Mirissa ± Weilgama, Riverston (Knuckles Forest Reserve), Nuwarraelliya - Horton Plains, Kirinda ± Yala National Park. 3(66) This trip all started by an invitation to see my sister in Thailand, plus a burning ambition to see the banteng (Bos javanicus). One bird I long have dreamt to see was Mrs Hume´s Phesant (Syrmaticus humiae). Since my latest trip to Thailand and Cambodia in my opinion was very rewarding I once again contacted Tu (Rattapon Kaichid) and Jan (Pitchaya Janhom) in Thailand. -

Breeding Biology of the Kakerori (Pomarea Dimidiata) on Rarotonga, Cook Islands

Breeding biology of the Kakerori (Pomarea dimidiata) on Rarotonga, Cook Islands By EDWARD K. SAUL'. HUGH A. ROBERTSON2' AND ANNA TIRAA1 'Takiturnu Conservation Area Project, PO. Box 81 7, Rarotonga, Cook Islands; ZScience & Research Unit, Department of Conservation, PO. Box lO-420, Welling- ton, New Zealand. ABSTRACT The breeding biology of Kakerori, or Rarotonga Flycatcher, (Pomarea dimidiata) ~~asstudied during ten years (1987-97) of experimental management aimed at saving this endangered monarch flycatcher from extinction. Kakerori remained territorial all year and were usually monogamous, Most birds kept the same mate from year to year, but pairs that bilrd to raise any young were more likely to divorce than successful pairs. Despite living in the tropics, Kakerori breeding was strictly seasonal. with eggs laid from early October to mid-February, and mostly in late October and early November. Nesting started earlier in years when October was very sunny Most pairs (74%) laid only one clutch, but some pairs laid up to four replacement clutches when nests failed.Three pairs (1%) successfully raised tnro broods in a season. Rat (Rattus spp.) predation was the principal cause of nest failure, especially of nests in pua (mpaea berteriana), the main fruiting tree used by rats during the Kakerori breeding season. Annual breeding productivity was initially poor (0.46 fledglings per breeding pair over two years) and the population was declining, but intensive management since 1989has led to a great increase in productivity (1.07 fledglings perb~edingpairover eight years) and the number ofKakerorihas increased from 29 birds in 1989 to a minimum of 153 birds in 1997. -

Species Status Assessment Report for the Tinian Monarch (Monarcha Takatsukasae)

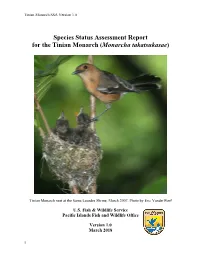

Tinian Monarch SSA Version 1.0 Species Status Assessment Report for the Tinian Monarch (Monarcha takatsukasae) Tinian Monarch nest at the Santa Lourdes Shrine, March 2007. Photo by Eric VanderWerf U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Version 1.0 March 2018 1 Tinian Monarch SSA Version 1.0 Suggested citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment for the Tinian Monarch. Version 1.0, March 2018. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, Honolulu, HI. 2 Tinian Monarch SSA Version 1.0 Executive Summary Introduction The Tinian Monarch is a small flycatcher bird endemic to the 39-mi2 (101 km2) island of Tinian, the second largest island in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), in the western Pacific Ocean. In 1970, the United States Fish & Wildlife Service (Service) listed the Tinian Monarch as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq). In 1987, the Service downlisted the Tinian Monarch to a threatened status, and in 2004, it was removed from the list of threatened species. In 2013, the Service was petitioned to list the Tinian Monarch as an endangered or threatened species under the Act, and as a result, the Service began a full review of the species’ status using the Species Status Assessment (SSA) approach. The SSA will serve as the foundational science for informing the Service’s decision whether or not to list the Tinian Monarch. This SSA report assesses the species’ ecology, current condition, and future condition under various scenarios.