Band from Rockall F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

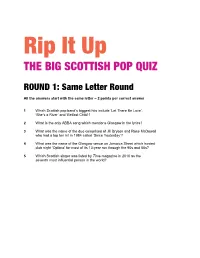

Big Scottish Pop Quiz Questions

Rip It Up THE BIG SCOTTISH POP QUIZ ROUND 1: Same Letter Round All the answers start with the same letter – 2 points per correct answer 1 Which Scottish pop band’s biggest hits include ‘Let There Be Love’, ‘She’s a River’ and ‘Belfast Child’? 2 What is the only ABBA song which mentions Glasgow in the lyrics? 3 What was the name of the duo comprised of Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall who had a top ten hit in 1984 called ‘Since Yesterday’? 4 What was the name of the Glasgow venue on Jamaica Street which hosted club night ‘Optimo’ for most of its 13-year run through the 90s and 00s? 5 Which Scottish singer was listed by Time magazine in 2010 as the seventh most influential person in the world? ROUND 1: ANSWERS 1 Simple Minds 2 Super Trouper (1st line of 1st verse is “I was sick and tired of everything/ When I called you last night from Glasgow”) 3 Strawberry Switchblade 4 Sub Club (address is 22 Jamaica Street. After the fire in 1999, Optimo was temporarily based at Planet Peach and, for a while, Mas) 5 Susan Boyle (She was ranked 14 places above Barack Obama!) ROUND 6: Double or Bust 4 points per correct answer, but if you get one wrong, you get zero points for the round! 1 Which Scottish New Town was the birthplace of Indie band The Jesus and Mary Chain? a) East Kilbride b) Glenrothes c) Livingston 2 When Runrig singer Donnie Munro left the band to stand for Parliament in the late 1990s, what political party did he represent? a) Labour b) Liberal Democrat c) SNP 3 During which month of the year did T in the Park music festival usually take -

The Evolution of Rural Farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: Investments and Inequalities Madalyn Watkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses 5-2012 The evolution of rural farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: investments and inequalities Madalyn Watkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/csesuht Recommended Citation Watkins, Madalyn, "The ve olution of rural farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: investments and inequalities" (2012). Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses. 6. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/csesuht/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Evolution of Rural Farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: Investments and Inequalities An Undergraduate Honors Thesis in the Crop, Soil, and Environmental Science Department Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the University of Arkansas Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences Honors Program by Madalyn Watkins April 2012 _____________________________________ _____________________________________ ____________________________________ I. Abstract The development and evolution of an agricultural system is influenced by many factors including binding constraints (limiting factors), choice of investments, and historic presence of land and income inequality. This study analyzed the development of two farming systems: mechanized, “economies of scale” farming in the Arkansas Delta and crofting in the Scottish Highlands. The study hypothesized that the current farm size in each region can be partially attributed to the binding constraints of either land or labor. -

CARRY on STREAMIN from EDINBURGH FOLK CLUB Probably the Best Folk Club in the World! Dateline: Wednesday 5 August 2020 Volume 1.05

CARRY ON STREAMIN from EDINBURGH FOLK CLUB Probably the best folk club in the world! Dateline: Wednesday 5 August 2020 Volume 1.05 CARRY ON STREAMIN You may recognise in our banner a ‘reworking’ of the of the Carrying Stream festival which EFC’s late chair, Paddy Bort, created shortly after the death of Hamish Henderson. After Paddy died in February 2017, EFC created the Paddy Bort Fund (PBF) to give financial assistance to folk performers who, through no fault of their own, fall on hard times. No-one contemplated anything like the coronavirus. Now we need to replenish PBF and have set a target of (at least) £10 000. Lankum at The Traverse Bar, Edinburgh There are two strands to Carry On EDINBURGH VENUES! So where are we now? Streamin - this publication and our YouTube channel where you will find, Douglas Robertson writes ... Many venues around the country have closed permanently, swathes of good staff have been every fortnight, videos donated by IT WOULD be a mistake to look back with laid off , countless well-established festivals some of the best folk acts around. nostalgia to the old days before Covid 19 as have been cancelled, and an army of musicians, Please donate to PBF as best you can, some kind of gig heaven in Edinburgh. agents, sound engineers and others are using the PayPal links we provide. A lethal mix - of a city council only too eager struggling to survive. to grant planning permission to every new The immediate future continues to look grim hotel, every proposed ‘student flat’ with social distancing determining that venues development, or ‘soon-to-be-AirBnB’ housing would be operating on a 25%-to-33% capacity, scheme combined with a university devouring in no way viable to cover costs and remunerate every available plot - ensured that scruff y professional artists. -

Sunset Side of Cape Breton Island

2014 ACTIVITY 2014 ActivityGUIDE Guide Page 1 SUNSET of Cape Breton SIDE • Summer Festivals • Scottish Dances • Kayaking • Hiking Trails • Horse Racing • Golf • Camping • Museums • Art Galleries • Great Food • Accommodations • Outdoor Concerts and more... WELCOME HOME www.invernesscounty.ca Page 2 2014 Activity Guide A must see during your visit to Discover Cape Breton Craft our Island is the Cape Breton Centre for Craft & Design in Art and craft often mirror the downtown Sydney. The stunning heritage, lifestyle and geography Gallery Shop contains the work of the region where artists live of over 70 Cape Breton artisans. and work. Nowhere is this more Hundreds of unique and one- evident than on Cape Breton of-a-kind items are on display Island with its stunning landscapes, and available for purchase. The rich history and traditions that Centre also hosts exhibitions have fostered a dynamic creativity and a variety of craft workshops Visual Artist Kenny Boone through the year. among its artisans. Fabric Dyeing by the Sea - Ann Schroeder Discover the connections between Cape Breton’s culture and Craft has a celebrated history geography and the work of our artisans by taking to the road with on our Island and, in many the Cape Breton Artisan Trail Map or download the App. Both will communities, craft remains set you on a trail of discovery and beauty with good measures of a living tradition among culture, history, adventure and charm. contemporary artisans who honour and celebrate both Artful surprises can be found tucked in the nooks and crannies form and function in endlessly throughout the Island: Raku potters on the North Shore, visual artists creative ways. -

Area Irish Music Events

MOHAWK VALLEY IRISH CULTURAL Volume 14, Issue 2 EVENTS NEWSLETTER Feb 2017 2017 GAIF Lineup: Old Friends, New Voices The official lineup for the 2017 Great American Irish Festival was announced at the Halfway to GAIF Hooley held January 29th at Hart’s Hill Inn in Whitesboro, with a broad array of veteran GAIF performers and an equal number of acts making their first appearance at the festival, and styles ranging from the delicate to the raucous. Headlining this year’s festival will be two of the Celtic music world’s most sought-after acts: the “Jimi Hendrix of the Violin,” Eileen Ivers, and Toronto-based Celtic roots rockers, Enter the Haggis. Fiery fiddler Eileen Ivers has established herself as the pre-eminent exponent of the Irish fiddle in the world today. Grammy awarded, Emmy nominated, London Symphony Orchestra, Boston Pops, guest starred with over 40 orchestras, original Musical Star of Riverdance, Nine Time All-Ireland Fiddle Champion, Sting, Hall and Oates, The Chieftains, ‘Fiddlers 3’ with Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg and Regina Carter, Patti Smith, Al Di Meola, Steve Gadd, founding member of Cherish the Ladies, movie soundtracks including Gangs of New York, performed for Presidents and Royalty worldwide…this is a short list of accomplishments, headliners, tours, and affiliations. Making a welcome return to the stage she last commanded in 2015, Eileen Ivers will have her adoring fans on their feet from the first note. Back again at their home away from home for the 11th time, Enter the Haggis is poised to rip it up under the big tent with all the familiar catchy songs that have made fans of Central New Yorkers and Haggisheads alike for over 15 years. -

Annual Report 2010

Annual Report 2010 Table of Contents 1 Chair’s Foreword 2 2 Fèis Facts 4 3 Key Services and Activities 5 4 Board of Directors 14 5 Staffing Report 15 6 Fèis Membership and Activities 17 7 Financial Statement 2009-10 28 Fèisean nan Gàidheal is a company limited by guarantee, registration number SC130071, registered with OSCR as a Scottish Charity, number SC002040, and gratefully acknowledges the support of its main funders Scottish Arts Council | The Highland Council | Bòrd na Gàidhlig | Highlands & Islands Enterprise Comhairle nan Eilean Siar | Argyll & Bute Council 1 Chair’s Foreword I am delighted to commend to you this year’s Annual Report From Fèisean nan Gàidheal. 2009-10 has been a challenging, and busy, year For the organisation with many highlights, notably the success oF the Fèisean themselves. In difficult economic times, Fèisean nan Gàidheal’s focus will remain on ensuring that support for the Fèisean remains at the heart of this organisation’s efforts. Gaelic drama also continued to flourish with drama Fèisean in schools, Meanbh-Chuileag’s perFormance tour of Gaelic schools and a successFul Gaelic Drama Summer School. In addition work was begun on radio drama in the Iomairtean Gàidhlig areas, continuing to make a valuable contribution to increasing the use oF Gaelic among young people. Fèisean nan Gàidheal continued to develop its use oF Gaelic language with Gaelic training to stafF, volunteers and tutors. Our service provides support to Fèisean to ensure that they produce printed and web materials bilingually, and seeks to help Fèisean ensure a greater Gaelic content in their activities. -

Folk & Roots Festival 2

Inverclyde’s Scottish Folk & Roots Festival 2014 5th October – 15th November Beacon Arts Centre, Greenock TICKETS: 01475 723723 www.beaconartscentre.co.uk FSundayAR 5thFAR October FROM YPRES FAR, FAR FROMSiobhan MillerYPRES N.B.7.30pm Because of the content of the material and the narrative, we would The music, songs and poetry of World War One from a Scottish perspective Sunday 5th October 3pm Welcome back... askMain that Theatre there is no applause until each half is finished. However, it is not to Inverclyde’s Scottish Folk & Roots a production of unremitting gloom, so if you would like to sing some of The Session Festival, brought to you courtesy of Far, Far From Ypres the choruses, please do so. Here’s some help: 1914 2014 Riverside Inverclyde. from “any village in Scotland”, telling of A free (ticketed) event at The Beacon Concessionary tickets of £10 available to his recruitment, training, journey to the Keep the Home-fires burning, When this bloody war is over Beacon Theatre, Greenock Last year’s festival saw audience ages all, subject to availability, until 4th Somme, and return to Scotland. Images This acoustic event is open to new-to- While your hearts are yearning, No more soldiering for me ranging from 8 to mid 80’s. Once again October, thereafter tickets priced at £15. from WW1 are projected onto a screen, Though your lads are far away When I get my civvy clothes on the-festival acts, subject to programme there’s something in the festival for deepening the audience’s understanding of everybody, hopefully offering community They dream of Home; Oh how happy I will be capacity, who register by Monday Ypres – a name forever embedded in the unfolding story. -

Minutes of Proceedings

House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee Minutes of Proceedings Session 2008–09 The Scottish Affairs Committee The Scottish Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Scotland Office (including (i) relations with the Scottish Parliament and (ii) administration and expenditure of the office of the Advocate General for Scotland but excluding individual cases and advice given within government by the Advocate General). Membership during Session 2008–09 Mr Mohammad Sarwar MP, (Lab, Glasgow Central) (Chairman) Mr Alistair Carmichael, (Lib Dem, Orkney and Shetland) Ms Katy Clark MP, (Lab, North Ayrshire & Arran) Mr Ian Davidson MP, (Lab, Glasgow South West) Mr Jim Devine MP, (Lab, Livingston) Mr Jim McGovern MP, (Lab, Dundee West) David Mundell MP, (Con, Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale) Lindsay Roy MP, (Labour, Glenrothes) Mr Charles Walker MP, (Con, Broxbourne) Mr Ben Wallace MP, (Con, Lancaster and Wyre) Pete Wishart MP, (SNP, Perth and North Perthshire) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/scottish_affairs_committee.cfm. Committee staff The staff of the Committee during Session 2008–09 were Charlotte Littleboy (Clerk), Nerys Welfoot (Clerk), Georgina Holmes-Skelton (Second Clerk), Duma Langton (Senior Committee Assistant), James Bowman (Committee Assistant), Becky Crew (Committee Assistant), Karen Watling (Committee Assistant) and Tes Stranger (Committee Support Assistant). -

Volume 2, Issue 1, Bealtaine 2003

TRISKELE A newsletter of UWM’s Center for Celtic Studies Volume 2, Issue 1 Bealtaine, 2003 Fáilte! Croeso! Mannbet! Kroesan! Welcome! Tá an teanga beo i Milwaukee! The language lives in Milwaukee! UWM has the distinction of being one of a small handful of colleges in North America offering a full program on the Irish language (Gaelic). The tradition began some thirty years ago with the innovative work of the late Professor Janet Dunleavy and her husband Gareth. Today we offer four semesters in conversational Gaelic along with complementary courses in literature and culture and a very popular Study Abroad program in the Donegal Gaeltacht. The study and appreciation of this richest and oldest of European vernacular languages has become one of the strengths and cornerstones of our Celtic Studies program. The Milwaukee community also has a long history of activism in support of Irish language preservation. Jeremiah Curtin, noted linguist and diplomat and the first Milwaukeean to attend Harvard, made it his business to learn Irish among the Irish Gaelic community of Boston. As an ethnographer working for the Smithsonian Institute, he was one of the first collectors of Irish folklore to use the spoken tongue of the people rather than the Hiberno-English used by the likes of William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory. Jeremiah Quinn, who left Ireland as a young man, capped a lifelong local commitment to Irish language and culture when in 1906, at the Pabst Theatre, he introduced Dr. Douglas Hyde to a capacity crowd, including the Governor, Archbishop, and other dignitaries. Hyde, one of the founders of the Gaelic League that was organized to halt the decline of the language, went on to become the first president of Ireland in 1937. -

Driving the Bow Fiddle and Dance Studies from Around the North Atlantic 2

DRIVING THE BOW fiddle and dance studies from around the north atlantic 2 edited by ian russell and mary anne alburger Driving the Bow Fiddle and Dance Studies from around the North Atlantic 2 The Elphinstone Institute Occasional Publications 6 General Editor – Ian Russell 1. A�er Columba – A�er Calvin: Community and Identity in the Religious Traditions of North East Scotland edited by James Porter 2. The Bedesman and the Hodbearer: The Epistolary Friendship of Francis James Child and William Walker edited by Mary Ellen Brown 3. Folk Song: Tradition, Revival, and Re-Creation edited by Ian Russell and David Atkinson 4. North-East Identities and Sco�ish Schooling The Relationship of the Sco�ish Educational System to the Culture of North-East Scotland edited by David Northcro� 5. Play It Like It Is Fiddle and Dance Studies from around the North Atlantic edited by Ian Russell and Mary Anne Alburger 6. Driving the Bow Fiddle and Dance Studies from around the North Atlantic 2 edited by Ian Russell and Mary Anne Alburger Elphinstone Institute Occasional Publications is a peer-reviewed series of scholarly works in ethnology and folklore. The Elphinstone Institute at the University of Aberdeen was established in 1995 to study, conserve, and promote the culture of North-East and Northern Scotland. Driving the Bow Fiddle and Dance Studies from around the North Atlantic 2 Edited by Ian Russell and Mary Anne Alburger The Elphinstone Institute University of Aberdeen 2008 Copyright © 2008 the Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, and the contributors While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in the Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, copyright in individual contributions remains with the contributors.