Parliament's Move to Wellington in 1865

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Cruise Natural Treasures of New-Zealand

Natural treasures of New-Zealand From 1/7/2022 From Dunedin Ship: LE LAPEROUSE to 1/18/2022 to Auckland On this cruise, PONANT invites you to discover New Zealand, a unique destination with a multitude of natural treasures. Set sail aboard Le Lapérouse for a 12-day cruise from Dunedin to Auckland. Departing from Dunedin, also called the Edinburgh of New Zealand, Le Lapérouse will cruise to the heart of Fiordland National Park, which is an integral part of Te Wahipounamu, UNESCOa World Heritage area with landscapes shaped by successive glaciations. You will discoverDusky Sound, Doubtful Sound and the well-known Milford Sound − three fiords bordered by majestic cliffs. The Banks Peninsula will reveal wonderful landscapes of lush hills and rugged coasts during your call in thebay of Akaroa, an ancient, flooded volcano crater. In Picton, you will discover the Marlborough region, famous for its vineyards and its submerged valleys. You will also sail to Wellington, the capital of New Zealand. This ancient site of the Maori people, as demonstrated by the Te Papa Tongarewa Museum, perfectly combines local traditions and bustling nightlife. From Tauranga, you can discover the many treasuresRotorua of : volcanoes, hot springs, geysers, rivers and gorges, and lakes that range in colour from deep blue to orange-tinged. Then your ship will cruise towards Auckland, your port of disembarkation. Surrounded by the blue waters of the Pacific, the twin islands of New Zealand are the promise of an incredible mosaic of contrasting panoramas. The information in this document is valid as of 9/24/2021 Natural treasures of New-Zealand YOUR STOPOVERS : DUNEDIN Embarkation 1/7/2022 from 4:00 PM to 5:00 PM Departure 1/7/2022 at 6:00 PM Dunedin is New Zealand's oldest city and is often referred to as the Edinburgh of New Zealand. -

New Zealand Wars Sources at the Hocken Collections Part 2 – 1860S and 1870S

Reference Guide New Zealand Wars Sources at the Hocken Collections Part 2 – 1860s and 1870s Henry Jame Warre. Camp at Poutoko (1863). Watercolour on paper: 254 x 353mm. Accession no.: 8,610. Hocken Collections/Te Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago Library Nau Mai Haere Mai ki Te Uare Taoka o Hākena: Welcome to the Hocken Collections He mihi nui tēnei ki a koutou kā uri o kā hau e whā arā, kā mātāwaka o te motu, o te ao whānui hoki. Nau mai, haere mai ki te taumata. As you arrive We seek to preserve all the taoka we hold for future generations. So that all taoka are properly protected, we ask that you: place your bags (including computer bags and sleeves) in the lockers provided leave all food and drink including water bottles in the lockers (we have a researcher lounge off the foyer which everyone is welcome to use) bring any materials you need for research and some ID in with you sign the Readers’ Register each day enquire at the reference desk first if you wish to take digital photographs Beginning your research This guide gives examples of the types of material relating to the New Zealand Wars in the 1860s and 1870s held at the Hocken. All items must be used within the library. As the collection is large and constantly growing not every item is listed here, but you can search for other material on our Online Public Access Catalogues: for books, theses, journals, magazines, newspapers, maps, and audiovisual material, use Library Search|Ketu. -

Arts and Culture Strategy

WELLINGTON CITY COUNCIL ARTS AND CULTURE STRATEGY December 2011 Te toi whakairo, ka ihiihi, ka wehiwehi, ka aweawe te ao katoa. Artistic excellence makes the world sit up in wonder. 1. Introduction Wellington is a creative city that welcomes and promotes participation, experimentation and collaboration in the arts. It has a tolerant population that is passionate and inquisitive. We acknowledge the unique position of Māori as tāngata whenua and the Council values the relationship it has with its mana whenua partners. Much of what makes New Zealand art unique lies in what makes New Zealand unique – our indigenous culture. As the capital of New Zealand, we are the seat of government and home to an international diplomatic community that connects us to the world. Wellington provides tertiary training opportunities in all art forms; has the highest rate of attendance in cultural activities1. Wellington’s arts and cultural environment is a strongly interconnected weave of: arts organisations (of many sizes); individual arts practitioners; volunteers; audience members; the general public; funders/supporters; and industries such as film and media. Wellington is fortunate to be home to many leading arts organisations and businesses that deliver world class experiences, products and services; attract and retain talented people; and provide essential development and career pathways for arts practitioners in the city. However, the current financial environment and other factors are damaging our arts infrastructure as organisations face reduced income from sponsorship, community trusts, and in some cases, public funding. This is constraining their ability to develop and deliver to their full capability, and some organisations may struggle to survive long term. -

Workingpaper

working paper The Evolution of New Zealand as a Nation: Significant events and legislation 1770–2010 May 2010 Sustainable Future Institute Working Paper 2010/03 Authors Wendy McGuinness, Miriam White and Perrine Gilkison Working papers to Report 7: Exploring Shared M āori Goals: Working towards a National Sustainable Development Strategy and Report 8: Effective M āori Representation in Parliament: Working towards a National Sustainable Development Strategy Prepared by The Sustainable Future Institute, as part of Project 2058 Disclaimer The Sustainable Future Institute has used reasonable care in collecting and presenting the information provided in this publication. However, the Institute makes no representation or endorsement that this resource will be relevant or appropriate for its readers’ purposes and does not guarantee the accuracy of the information at any particular time for any particular purpose. The Institute is not liable for any adverse consequences, whether they be direct or indirect, arising from reliance on the content of this publication. Where this publication contains links to any website or other source, such links are provided solely for information purposes and the Institute is not liable for the content of such website or other source. Published Copyright © Sustainable Future Institute Limited, May 2010 ISBN 978-1-877473-55-5 (PDF) About the Authors Wendy McGuinness is the founder and chief executive of the Sustainable Future Institute. Originally from the King Country, Wendy completed her secondary schooling at Hamilton Girls’ High School and Edgewater College. She then went on to study at Manukau Technical Institute (gaining an NZCC), Auckland University (BCom) and Otago University (MBA), as well as completing additional environmental papers at Massey University. -

James Macandrew of Otago Slippery Jim Or a Leader Staunch and True?

JAMES MACANDREW OF OTAGO SLIPPERY JIM OR A LEADER STAUNCH AND TRUE? BY RODERICK JOHN BUNCE A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2013 iii ABSTRACT James Macandrew, a Scotsman who migrated to Dunedin in 1851, was variously a businessman, twice Superintendent of Otago Province, an imprisoned bankrupt and a Minister of the Crown. He was an active participant in provincial and colonial politics for 36 years and was associated with most of the major political events in New Zealand during that time. Macandrew was a passionate and persuasive advocate for the speedy development of New Zealand’s infrastructure to stimulate the expansion of settlement. He initiated a steamer service between New Zealand and Australia in 1858 but was bankrupt by 1860. While Superintendent of Otago in 1860 and 1867–76 he was able to advance major harbour, transport and educational projects. As Minister of Public Works in George Grey’s Ministry from 1878–79 he promoted an extensive expansion of the country’s railway system. In Parliament, he was a staunch advocate of easier access to land for all settlers, and a promoter of liberal social legislation which was enacted a decade later by the Seddon Government. His life was interwoven with three influential settlers, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, Julius Vogel and George Grey, who variously dominated the political landscape. Macandrew has been portrayed as an opportunist who exploited these relationships, but this study will demonstrate that while he often served these men as a subordinate, as a mentor he influenced their political beliefs and behaviour. -

Overspill Alternative Jor South Auckland

Photograph by courtesy Dunedin City Council. • Aerial photogrammetric mapping • Large scale photo enlargements • Mosaics • Ground control surveys AERO SURVEYS New Zea and LTD. P.O. Box 444 Tauranga Telephone 88-166 TOWN PLANNING QUARTERLY •Layout, Design &Production: COVER: "WELLINGTON Editor: J. R. Dart WIND" EVENING POST. Technical Editor: M. H. Pritchard D. Vendramini Department of Town Planning. J. Graham University of Auckland. MARCH 1974 NUMBER 25 EDITORIAL COMMUNITY PROPERTY DEREK HALL CASEBOOK CHRISTINE MOORE A CONTRAST IN SETTLEMENT: AUCKLAND AND WELLINGTON 1840-41 RICHARD BELLAMY 17 ABOUT WATER T.W. FOOKES 24 OVERSPILL ALTERNATIVE FOR SOUTH AUCKLAND. (PART 2) 28 CONFERENCES SYLVIA McCURDY 29 LETTER FROM SCOTLAND D.H. FR EESTON 33 WIND ENVIRONMENT OF BUILDINGS 38 INSTITUTE AFFAIRS Town Planning Quarterly is the official journal of the New Address all correspondence to the Editor: Town Planning Zealand Planning Institute Incorporated, P.O. Box 5131, Quarterly, P.O. Box 8789, Symonds Street, Auckland 1. WeUington. Telephone/Telegrams: 74-740 The Institute does not accept responsibility for statements made or opinions expressed in this Journal unless this responsibility is expressly acknowledged. Printed by Published March, June, September, December. Scott Printing Co. Ltd., Annual Subscription: $3 (New Zealand and Australia) 29-31 Rutland Street, post free, elsewhere $NZ. 4.50 Auckland 1. The Mayor of Auckland caught the headlines recently with his suggestion that a group be formed to examine the extent and nature of the metropolitan area's future growth. The idea, so far anyway, seems not to have been taken very seriously, but is is one that is worth pursuing. -

Living Through History Worksheet - Lesson Three Copyright National Army Museum Te Mata Toa 1 He Waka Eke Noa We Are All in This Together

Living through History Worksheet - Lesson Three Copyright National Army Museum Te Mata Toa 1 He waka eke noa We are all in this together History isn’t something that happens to someone else. Right now, you are living through an extraordinary event that is changing the New Zealand way of life: the COVID-19 pandemic. Future students might look back on this moment and ask: how did they feel? How did they make it through? We can ask the same questions about another generation of Kiwis who lived through extraordinary times: The Ngā Puhi people and the settlers in Northland in 1840. Then, like now, a major crisis forced everyday New Zealanders to reconsider the way that they were used to living. With the changes and challenges, people faced uncertain and unpredictable futures. Ngā Puhi were determined to uphold their rangitiratanga as incresing numbers of Pākehā disrupted their way of life. For each of the activities below: - Read about what was happening in Northland. - Reflect on how everyone was thinking and feeling. - Respond to the questions or instructions at the end of each activity. Share your answers with your classmates and teacher! We’ll all have our own unique experiences, and we can all learn just as much from each other as we can from our nation’s history. Living through History Worksheet - Lesson Three Copyright National Army Museum Te Mata Toa 2 Activity 1: What was going on? Prior to 1840 Ngā Puhi (a Māori iwi, tribe) had control and sovereignty over the northern part of New Zealand. There were a growing number of Pākehā traders, settlers and missionaries moving into the same area – some, but not all, respected Ngā Puhi. -

Maturita Card 34: Australian and New Zealand Cities

Maturita Card 34: Australian and New Zealand Cities z What are the most famous cities in Australia? stretches over a kilometer, and visitors can climb over Most of the cities can be found on / are situated along it and admire the view of the harbour and the Opera the coastline of Australia because the interior of House. The Rocks is the historic part of Sydney, with the country is a desert. Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane buildings from the 18th century. To enjoy the ocean, and Canberra can be found in the east, Darwin in visit the most famous beach in Sydney: Bondi Beach. the north, and Perth in the west. z What do you know about Melbourne? z What is the capital of Australia? Melbourne is Australia‘s second largest city and The capital city of Australia is Canberra, although the capital of Victoria province. It is also Australia’s most people think it is Sydney or Melbourne. The city is cultural capital because many musicians and comedians unusual because it was entirely planned and designed started there. Three major annual international sporting by an American architect, Walter Burley Griffin. It events take place there: the Australian Open (Grand Slam has a modern look and is sometimes compared to tennis tournament), the Melbourne Cup (horse racing) Washington D.C. because both cities are built around and the Australian Grand Prix (Formula One). geometric shapes, like triangles and squares. In z What other Australian cities can you visit the centre of the city there is an artificial / man-made and why? lake, Lake Burley Griffin, withThe Captain James Cook Memorial Water Jet, a stream of water that reaches On the east coast, you can find Brisbane, the third largest up to 150 m high. -

How Finance Colonised Aotearoa, Catherine Cumming

his paper intervenes in orthodox under- Tstandings of Aotearoa New Zealand’s colonial history to elucidate another history that is not widely recognised. This is a financial history of colonisation which, while implicit in existing accounts, is peripheral and often incidental to the central narrative. Undertaking to reread Aotearoa New Zealand’s early colonial history from 1839 to 1850, this paper seeks to render finance, financial instruments, and financial institutions explicit in their capacity as central agents of colonisation. In doing so, it offers a response to the relative inattention paid to finance as compared with the state in material practices of colonisation. The counter-history that this paper begins to elicit contains important lessons for counter- futures. For, beyond its implications for knowledge, the persistent and violent role of finance in the colonisation of Aotearoa has concrete implications for decolonial and anti- capitalist politics today. | 41 How Finance Colonised Aotearoa: A Concise Counter-History CATHERINE GRACE CUMMING This paper intervenes in orthodox understandings of Aotearoa New Zealand’s colonial history to elucidate another history that is not widely recognised.1 This is a financial history of colonisation which, while implicit in orthodox accounts, is peripheral to, and often treated as incidental in, the central narrative. Finance and considerations of economy more broadly often have an assumed status in historical narratives of this country’s colonisation. In these, finance is a necessary condition for the colonial project that seems to need no detailed inquiry. While financial mechanisms such as debt, taxes, stocks, bonds, and interest are acknowledged to be instrumental to the pursuit of colonial aims, they are, in themselves, viewed as neutral. -

The Evolution of Socio-Political Cartoon Satire In

The Evolution of Sodo-Polltical Cartoon Satire in the New Zealand Press During the 19th and Early 20th centuries: its Role in Justifying the Alienation of Maori lands. thesis submitted to fulfill the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in, History by G.. G.Vince ~acDonald ----------()---------- University Canterbury March 1995 N CONTENTS PAGE Prefa ce ......... HO ...............ee ••••••••••••••••••••••• "OO •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••41..... ii Chapter one••••• The Early Media Controllers Establish............ 19 their Agenda Chapter two..... The Formative Years of Sccio... PcUtical.......... 58 Cartoon Satire in New Zealand Chapter three•• The New Zealand Herald and Auckland...... 16 Weeklv News: the Main Disseminators of Construded Reality through Cartoons: an Agenda Revealed .. Chapter four••• Wilson and Horton Narrow the FOcus ..... m •• and Widens its Audience Chapter five..... Wilson and Horton's Cartoonist Par .. '........... 118 Excellence: Trevor lloyd Epi log ue•••• ee••••• K." ...6 •• "."."•• " •• "."•••••••••••• e.O.~8.e ................................6 ••••••• The main media agenda Illustrated: annotated excerpts from the New Zealand Herald and the Auckland Weekly News 1900 to 1930. Bibliography................................................... ce ...................................... 08 191 I Abstract TIns thesis examines the evolution of socio-political cartoon satire and how it came to be used as a weapon in the Pakeha media campaign to facilitate the total alienation of Maori land in New Zealand in the nineteenth century and the first three decades of the Twentieth century. The thesis begins by examining the role of key media controllers and relevant elements of their backgrounds. Outstanding from among these elements is the initial overlap of the business and political interests of the key players. Intrinsic to this overlap is the split wmch occurred from about the 1860s. -

Bilateral Visit to New Zealand and Samoa -- Auckland and Wellington

Report of the Canadian Parliamentary Delegation respecting its participation at the Bilateral Visit to New Zealand and Samoa Canadian Branch of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (APC) Auckland and Wellington, New Zealand and Apia, Samoa March 1 to 10, 2019 Report A delegation of the Canadian Branch of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association visited New Zealand and Samoa from March 1 to 10, 2019. Ms. Yasmin Ratansi, M.P. and Chair of the Canadian Branch, led the delegation, which also included the Hon. Vernon White, Senator, Mr. Richard Cannings, M.P., and Mr. Sukh Dhaliwal, M.P. Mr. Rémi Bourgault, Secretary of the Canadian Branch, accompanied the delegation. The Association’s constitution encourages visits between member countries with the objective of giving parliamentarians the opportunity to discuss matters of common interest in bilateral relations and issues involving the Commonwealth organization as a whole. The purpose of the visit to New Zealand and Samoa was to strengthen ties with our partners in the Commonwealth’s Pacific Region and exchange ideas in areas of mutual interest. Numerous subjects were covered during the bilateral visit, including the state of parliamentary democracy in relation to the Westminster system, the challenges of climate change, security, trade and investment, gender-based violence, and relations with Indigenous peoples. VISIT TO NEW ZEALAND Geography New Zealand is an island state located in the South Pacific Ocean, southeast of Australia. Its landmass is 264,537 square kilometres – more than twice the size of Newfoundland island. It consists of two main islands to the North and South as well as a number of smaller islands, though the majority of New Zealanders live on the North Island. -

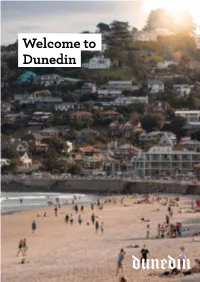

'Welcome to Dunedin' Information

Welcome to Dunedin 2 CONTACTS Useful Dunedin Contacts ENTERPRISE DUNEDIN i-SITE DUNEDIN DUNEDIN CONVENTION VISITOR CENTRE Enterprise Dunedin, as the Regional Tourism BUREAU The i-SITE Dunedin Visitor Centre is the Organisation, is proud to be the first point of number one place for visitors to the region. contact for all information relating to Dunedin The Dunedin Convention Bureau is available The team have extensive local knowledge city and the region of Otago. Enterprise to assist with arranging meeting, conference, and information about all of the attractions, Dunedin is active in international and regional event or incentive programmes. With local accommodation, dining establishments and markets, providing staff training, product news knowledge and contacts, the bureau team is tours available in and around the city. They and product updates. Available information there to give impartial recommendations, and also provide a booking service. also includes marketing material, itinerary connect clients with the right people. The Bureau also can arrange site visits, prepare suggestions, and hosting media and business CONTACT DETAILS event familiarisations. itineraries, and create bespoke bid documents. Phone: +64 3 474 3300 CONTACT DETAILS CONTACT DETAILS Email: [email protected] Phone Number: +64 3 474 3457 Physical Address: 50 The Octagon, Dunedin Fax Number: +64 3 471 8021 50 The Octagon www.dunedin.govt.nz/isite Postal Address: PO Box 5045 Email: [email protected] Dunedin 9058 www.dunedinnz.com/meet NEW ZEALAND DUNEDIN