Bone Machine (1992): What the Hell Is Tom Waits Singing About? Imperative and Permanent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Denson Master Song List 2020

Bob Denson Master Song List Alphabetical by Artist/Band Name A Amos Lee - Arms of a Woman - Keep it Loose, Keep it Tight - Night Train - Sweet Pea Amy Winehouse - Valerie Al Green - Let's Stay Together - Take Me To The River Alicia Keys - If I Ain't Got You - Girl on Fire - No One Allman Brothers Band, The - Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More - Melissa - Ramblin’ Man - Statesboro Blues Arlen & Harburg (Isai K….and Eva Cassidy and…) - Somewhere Over the Rainbow Avett Brothers - The Ballad of Love and Hate - Head Full of DoubtRoad Full of Promise - I and Love and You B Bachman Turner Overdrive - Taking Care Of Business Band, The - Acadian Driftwood - It Makes No Difference - King Harvest (Has Surely Come) - Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, The - Ophelia - Up On Cripple Creek - Weight, The Barenaked Ladies - Alcohol - If I Had A Million Dollars - I’ll Be That Girl - In The Car - Life in a Nutshell - Never is Enough - Old Apartment, The - Pinch Me Beatles, The - A Hard Day’s Night - Across The Universe - All My Loving - Birthday - Blackbird - Can’t Buy Me Love - Dear Prudence - Eight Days A Week - Eleanor Rigby - For No One - Get Back - Girl Got To Get You Into My Life - Help! - Her Majesty - Here, There, and Everywhere - I Saw Her Standing There - I Will - If I Fell - In My Life - Julia - Let it Be - Love Me Do - Mean Mr. Mustard - Norwegian Wood - Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da - Polythene Pam - Rocky Raccoon - She Came In Through The Bathroom Window - She Loves You - Something - Things We Said Today - Twist and Shout - With A Little Help From My Friends - You’ve -

Cd Musicali – Rock Artisti Stranieri

CD MUSICALI – ROCK ARTISTI STRANIERI Leonard Cohen – Dear Heather R. E. M. – Around the Sun Steely Dan – Aja Yes – Close to the Edge Faiport Convention – Unhalfbricking MC 5 – Kick out the jams Black Sabbath – Paranoid The Strokers – Room on fire Jain Mitchell – Blue Bang Gang – Something wrong Jamiroquai – A fun adyssey Moby – I like to score Garky’s Zygotic Mynci – How long feel that summer in my heart Radiohead – I might be wrong live recording Bob Marley & The Wailers – Uprising Alanis Morisette – Under Rug Swept Lou Reed – NYC Man Blur – Think Tank Bill Bragg & Wilco – Mermaid Avenue Radioheah – Hai to the thief Peter Gabriel – Hit Elvis Costello – North The Rocking Chairs – Sparkes of Passion Rickie Lee Jones _ The evening of my best day The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet Robert Wyatt – Rock Bottom Patti Smith Group – Wave The Kills – Keep on your mean side Fairport Convention – Full house Era – Tha masy Belle e Sebastian – Dear catastrophe waitress Van Marrison – What’s wrong with this picture? Nick Drake – Tink Moon The Black Eyed Peas – Elephunk Tom Waits – Real Gone The Who – Live at Leeds Joy Division – Substance 1977 – 1980 Elliot Smith – Figure 8 Caravan – In the Land of Grey and Pink Happy Trails – Quicksilver Messenger Service The Allman Brothers Band – Eat a Peach Julian Cope – Fried Mudhoney – Superfuzz Bigmuff plus Early Singles Jane’s Addiction – Ritual de lo habitual 1 Eels – Daisies of the galaxy Mallard – In a different climate Frank Zappa – Over – nite Sensation Tom Waits – Blood Money Patty Smith – Land ( 1995 -

Ayden Graham Complete Song List 50S/60S/70S

ayden graham complete song list 50s/60s/70s 1. Nature Boy Eden Ahbez 2. Across The Universe The Beatles 3. All You Need Is Love The Beatles 4. Blackbird The Beatles 5. Dear Prudence The Beatles 6. Eleanor Rigby The Beatles 7. Hey Bulldog The Beatles 8. Michelle The Beatles 9. She Said, She Said The Beatles 10. Taxman The Beatles 11. Black Orpheus Luis Bonfa 12. Tonight Will Be Fine Leonard Cohen 13. All Along The Watchtower Bob Dylan 14. I Want You Bob Dylan 15. Mellow Yellow Donovan 16. Stand By Me Ben E. King 17. You Really Got Me The Kinks 18. Fever Peggy Lee 19. Could You Be Loved Bob Marley 20. One Harry Nilsson 21. Me and My Arrow Harry Nilsson 22. Moonshadow Cat Stevens 23. The Wind Cat Stevens 24. Wild World Cat Stevens 25. Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers 26. Lovely Day Bill Withers 27. Use Me Bill Withers 28. Heart of Gold Neil Young 80s/90s/2000s 1. The Golden Age Beck 2. First Day of My Life Bright Eyes 3. Don't Panic Coldplay 4. In My Place Coldplay 5. Politik Coldplay 6. Yellow Coldplay 7. 9 Crimes Damien Rice 8. Amie Damien Rice 9. Cannonball Damien Rice 10. Cheers Darlin’ Damien Rice 11. Delicate Damien Rice 12. Elephant Damien Rice 13. The Blowers Daughter Damien Rice 14. The Animals Were Gone Damien Rice 15. Older Chests Damien Rice 16. Volcano Damien Rice 17. The General Dispatch 18. Any Day Now Elbow 19. Powder Blue Elbow 20. Lay Me Down Glen Hansard 21. -

New Dvds – December - 2013

NEW DVDS – DECEMBER - 2013 FEATURE FILMS: GANGS OF NEW YORK A GOOD DAY TO DIE HARD BEFORE MIDNIGHT HOMELAND: SEASON 1 PACIFIC RIM TOO BIG TO FAIL SNITCH THE GREAT GATSBY GET THE GRINGO FREELANCERS LAWLESS THE CONJURING LORD OF THE FLIES SMASHED BYZANTIUM THE HALLOWEEN COLLECTION THE BOONDOCKS: SEASONS 1,2,3 HOMELAND: SEASON 2 THE ICEMAN SCHINDLER’S LIST PRINCE AVALANCHE WORLD WAR Z PEEPLES MEMENTO LUTHER LUTHER 2 IN THE FOG HUSBANDS AND WIVES THE LAST STAND KISS KISS BANG BANG THE ATTACK BEHIND THE CANDELABRA CURSE OF CHUCKY CLOUD ATLAS HOT FUZZ BARBARA ALIEN TRIPLE PACK SUPERBAD BLOW OUT HEAD OF STATE TRUST WHITE DAWN BREAKING BAD: FINAL SEASON REN & STIMPY SHOW UNCUT: SEASONS 1&2 RESOLUTION EASTERN PROMISES DOCUMENTARIES: THE WEIGHT OF THE NATION WE STEAL SECRETS RISE OF THE DRONES THE CENTRAL PARK FIVE RAISING ADAM LANZA THE WAITING ROOM CONSTITUTION USA MY TRIP TO AL-QAEDA LATINO AMERICANS CALL ME KUCHU GOOD HAIR KEY & PEELE: SEASON 1 COLIN QUINN: LONG STORY SHORT BLACKFISH I’M CAROLYN PARKER MEA MAXIMA CULPA CLIMATE OF DOUBT CHASING ICE INTO THE DEEP STRONGMAN THE DADDY OF ROCK N ROLL DECEPTIVE PRACTICE NEW MUSIC CD’s December 2013 POP Julia Holter Loud City Song Tye Tribbett Greater Than Drake Nothing Was the Same Darkside Psychic Tom Waits Bad as Me Bone Machine Justin Timberlake The 20/20 Experience Eccentric Soul The Forte Label Percy Sledge The Platinum Collection Valerie June Pushin Against a Stone Neko Case The Worse Things Get Janelle Monae The Electric Lady Velvet Underground 45th Anniversary Remaster Roky Erickson Gremlins Have Pictures COUNTRY Brandy Clark 12 Stories CLASSICAL Massimo Giordano Amore E Tormento WORLD Ana Tijoux La Bala Luis Coronel Con La Frente En Alto Rodion GA The Lost Tapes . -

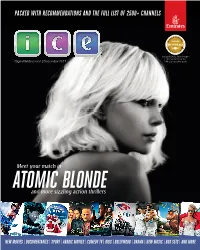

Packed with Recommendations and the Full List of 2500+ Channels

PACKED WITH RECOMMENDATIONS AND THE FULL LIST OF 2500+ CHANNELS Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment for the Digital Widescreen | December 2017 13th consecutive year! Meet your match in ATOMIC BLONDE and more sizzling action thrillers NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE OBCOFCDec17EX2.indd 51 09/11/2017 15:13 EMIRATES ICE_EX2_DIGITAL_WIDESCREEN_62_DECEMBER17 051_FRONT COVER_V1 200X250 44 An extraordinary ENTERTAINMENT experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. THE LATEST Information… Communication… Entertainment… Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- MOVIES flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss movies and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 527 ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS STAY CONNECTED 4 Connect to the 1500 OnAir Wi-Fi network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s 1 Choose a channel Go straight to your chosen programme by typing the channel WATCH LIVE TV 2 3 number into your handset, or use the onscreen channel entry pad Live news and sport channels are available on 1 3 Swipe left and Search for Move around most fl ights. Find out right like a tablet. movies, TV using the games more on page 9. Tap the arrows shows, music controller pad onscreen to and system on your handset scroll features and select using the green game 2 4 Create and Tap Settings to button 4 access your own adjust volume playlist using and brightness Favourites Home Again Many movies are 113 available in up to eight languages. -

MTO 22.4: Thomas, Text and Temporality

Volume 22, Number 4, December 2016 Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory * Margaret E. Thomas NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.4/mto.16.22.4.thomas.php KEYWORDS: Tom Waits, rhythm, hypermeter, popular music, lyrics, rhythmic irregularity, voice ABSTRACT: This article considers phrase structure, hypermeter, and lyrics in three songs by Tom Waits, examining the particular ways that temporal regularity and irregularity interact with poetic structure, musical style, and vocal performance in Waits’s music. Subtle and ambiguous hypermetrical shifts are uncovered in “Green Grass,” whereas “Black Wings” utilizes conspicuously conflicting phrase lengths to enhance its textural meaning. In “Dead and Lovely” Waits creates temporal disturbances by shifting the placement of four-measure phrases relative to hypermetrical downbeats and upbeats. Received July 2016 Introduction [1.1] American singer-songwriter Tom Waits opens his 2004 song “Green Grass” with this quatrain: Lay your head where my heart used to be Hold the earth above me Lay down in the green grass Remember when you loved me The four lines—each a directive—draw the listener into the song as they unfurl a rambling narrative packed with evocative imagery, wistful sorrow, and intimacy. It is a bold opening, and it encapsulates much of what is distinctive about Waits: the subject matter is dark and perplexing, and the poetic structure is irregular and a bit playful. The lines have 9, 6, 6, and 7 syllables, respectively. Their rhyme scheme plays out in two layers: a literal aaba pattern (“be,” “me,” “grass,” “me”), and an elongated near-rhyme pattern in lines two and four (“above me” and “loved me”). -

GRAB a GRAMMY the Big News of Last Month About How It Felt to Win the As You Probably Know the Has to Be the Fantastic Victory Best Alternative Album

1 News Updates COLDPLAY Coldplay Interview (10/99) Will Champion Profile E-ZINE • ISSUE 1 • 04.02 Interview with Phil Harvey GRAB A GRAMMY The Big News of last month about how it felt to win The As you probably know the has to be the fantastic victory Best Alternative Album. recording of the second at the 44th Annual Grammy Chris was thrilled: "Of course album is now complete and Awards. Jonny, Will, Guy and we're absolutely delighted to the mixing process has Phil were at the prestigious get this Grammy thing even begun. Chris also told me event in Los Angeles. though it's total nonsense, it's that he is very happy with the Chris was absent from the still good nonsense to win". results and assures me they have made a great album. ceremony as he was in I spoke to him just as the England in the studio working hour had swung into his 25th The band had a break after on the follow up to birthday and he was on his their time recording and Parachutes. I spoke to him way to the studio to play went off to do various things. Click to watch Interview piano. Chris visited the island of Haiti (Dominican Republic) as part of an Oxfam charity venture. This snippet is taken as it appeared in a local newspaper. British Coldplay rock star, Chris Martin, was in the DR last week. He came on an invitation from Oxfam United Kingdom to visit coffee farms in the southern province of San Cristobal. -

Tom Waits Swordfishtrombones Free

FREE TOM WAITS SWORDFISHTROMBONES PDF David Smay | 144 pages | 15 Feb 2008 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780826427823 | English | London, United Kingdom Swordfishtrombones - Tom Waits | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic More Images. Please enable Javascript to take full advantage of our site features. Edit Master Release. JazzRock. Blues RockLoungeTom Waits Swordfishtrombones. Francis Tom Waits Swordfishtrombones Arranged By. Frank Mulvey Art Direction. Michael Solomon 2 Coordinator. Bill Jackson Engineer. Peggy McCreary Engineer. Richard McKernan Engineer. Arlyne Rothberg Management. Bill Gerber Management. Jeff Sanders Mastered By. But considering where he was coming from, Tom Waits Swordfishtrombones is such a wide range of music here- I'd say a perfect balance between what was and what will be. So many different feelings and energy at every turn. Just a brilliant album. This Canadian pressing sounds very good. Reply Notify me Helpful. So alive. Note: only pressing i heard from this album. No crackle at all, recommended. FromThisPosition June 7, Report. MrShocktime May 3, Report. Did anyone else receive either with theirs? The quality is actually spectacular! One of the best vinyl records I own. Reply Notify me 1 Helpful. Add all to Wantlist Remove all from Wantlist. Have: Want: Avg Rating: 4. Listened by hipp-e. First Tom Waits Swordfishtrombones about My Music by chris. Absolutely Classic Albums by Joost Best albums of by dj-maus. Shore Leave. Dave The Butcher. Johnsburg, Illinois. Town With No Cheer. In The Neighborhood. Frank's Wild Years. Down, Down, Down. Soldier's Things. Gin Soaked Boy. Trouble's Braids. Island RecordsIsland Records. Sell This Version. Island Records. Asylum Records. -

Clangxboomxstea ... Vxtomxwaitsxxlxterxduo.Pdf

II © Karl-Kristian Waaktaar-Kahrs 2012 Clang Boom Steam – en musikalsk lesning av Tom Waits’ låter Forsidebilde: © Massimiliano Orpelli (tillatelse til bruk er innhentet) Konsertbilde side 96: © Donna Meier (tillatelse til bruk er innhentet) Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo III IV Forord Denne oppgaven hadde ikke vært mulig uten støtten fra noen flotte mennesker. Først av alt vil jeg takke min veileder, Stan Hawkins, for gode innspill og råd. Jeg vil også takke ham for å svare på alle mine dumme (og mindre dumme) spørsmål til alle døgnets tider. Spesielt i den siste hektiske perioden har han vist stor overbærenhet med meg, og jeg har mottatt hurtige svar selv sene fredagskvelder! Jeg skulle selvfølgelig ha takket Tom Waits personlig, men jeg satser på at han leser dette på sin ranch i «Nowhere, California». Han har levert et materiale som det har vært utrolig morsomt og givende å arbeide med. Videre vil jeg takke samboeren min og mine to stadig større barn. De har latt meg sitte nede i kjellerkontoret mitt helg etter helg, og all arbeidsroen jeg har hatt kan jeg takke dem for. Jeg lover dyrt og hellig å gjengjelde tjenesten. Min mor viste meg for noen år siden at det faktisk var mulig å fullføre en masteroppgave, selv ved siden av en krevende fulltidsjobb og et hektisk familieliv. Det har gitt meg troen på prosjektet, selv om det til tider var slitsomt. Til sist vil jeg takke min far, som gikk bort knappe fire måneder før denne oppgaven ble levert. Han var alltid opptatt av at mine brødre og jeg skulle ha stor frihet til å forfølge våre interesser, og han skal ha mye av æren for at han til slutt endte opp med tre sønner som alle valgte musikk som sin studieretning. -

Led Zeppelin R.E.M. Queen Feist the Cure Coldplay the Beatles The

Jay-Z and Linkin Park System of a Down Guano Apes Godsmack 30 Seconds to Mars My Chemical Romance From First to Last Disturbed Chevelle Ra Fall Out Boy Three Days Grace Sick Puppies Clawfinger 10 Years Seether Breaking Benjamin Hoobastank Lostprophets Funeral for a Friend Staind Trapt Clutch Papa Roach Sevendust Eddie Vedder Limp Bizkit Primus Gavin Rossdale Chris Cornell Soundgarden Blind Melon Linkin Park P.O.D. Thousand Foot Krutch The Afters Casting Crowns The Offspring Serj Tankian Steven Curtis Chapman Michael W. Smith Rage Against the Machine Evanescence Deftones Hawk Nelson Rebecca St. James Faith No More Skunk Anansie In Flames As I Lay Dying Bullet for My Valentine Incubus The Mars Volta Theory of a Deadman Hypocrisy Mr. Bungle The Dillinger Escape Plan Meshuggah Dark Tranquillity Opeth Red Hot Chili Peppers Ohio Players Beastie Boys Cypress Hill Dr. Dre The Haunted Bad Brains Dead Kennedys The Exploited Eminem Pearl Jam Minor Threat Snoop Dogg Makaveli Ja Rule Tool Porcupine Tree Riverside Satyricon Ulver Burzum Darkthrone Monty Python Foo Fighters Tenacious D Flight of the Conchords Amon Amarth Audioslave Raffi Dimmu Borgir Immortal Nickelback Puddle of Mudd Bloodhound Gang Emperor Gamma Ray Demons & Wizards Apocalyptica Velvet Revolver Manowar Slayer Megadeth Avantasia Metallica Paradise Lost Dream Theater Temple of the Dog Nightwish Cradle of Filth Edguy Ayreon Trans-Siberian Orchestra After Forever Edenbridge The Cramps Napalm Death Epica Kamelot Firewind At Vance Misfits Within Temptation The Gathering Danzig Sepultura Kreator -

I Used to Think Reading Was "Lame" and "Boring". MTV Really Messed Us up :P Then I Read One Book

I used to think reading was "lame" and "boring". MTV really messed us up :P Then I read one book.... it changed my life... so I read another... it changed again... so I read another and then another. The process continued on until I became a whole new animal. Books have made my life better in every possible way from mental growth to physical and spiritual growth. Because of their immense effect on my life, I want to share the books I have read with people so they can start growing and taking control of their lives. I want you to become the best person you can possibly be! I figure that the books I've read, that have made my life better, can 100% make your life better! If you don't know where to start, pick a book from my list! If I have read it more than once, it was for a reason. You probably don't think you have time to read books. That's okay though, because I prove that's not true at all. You have time to read if you use the smart tricks I show you at the bottom of this page. The 48 Laws Of Power by Robert Greene *I've Read It 15+ times Mastery by Robert Greene 5+ times The 50th Law by Robert Greene 3+ Times Think and Grow Rich Napoleon Hill 4 times The Slight Edge by Jeff Olson 2 times 4 Hour Work Week by Tim Ferriss 2 Times The Power Of Now by Eckart Toll Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future The Master Key System To Riches Napoleon Hill Out Of Your Mind By Alan Watts 100 Ways To Motivate Yourself by Steve Chandler 5 Times The Strangest Secret by Earl Nightingale 3 times Eleven Keys To Excellence by John Maxwell The Winner's Brain. -

Selling Or Selling Out?: an Exploration of Popular Music in Advertising

Selling or Selling Out?: An Exploration of Popular Music in Advertising Kimberly Kim Submitted to the Department of Music of Amherst College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with honors. Faculty Advisor: Professor Jason Robinson Faculty Readers: Professor Jenny Kallick Professor Jeffers Engelhardt Professor Klara Moricz 05 May 2011 Table of Contents Acknowledgments............................................................................................................... ii Chapter 1 – Towards an Understanding of Popular Music and Advertising .......................1 Chapter 2 – “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke”: The Integration of Popular Music and Advertising.........................................................................................................................14 Chapter 3 – Maybe Not So Genuine Draft: Licensing as Authentication..........................33 Chapter 4 – Selling Out: Repercussions of Product Endorsements...................................46 Chapter 5 – “Hold It Against Me”: The Evolution of the Music Videos ..........................56 Chapter 6 – Cultivating a New Cultural Product: Thoughts on the Future of Popular Music and Advertising.......................................................................................................66 Works Cited .......................................................................................................................70 i Acknowledgments There are numerous people that have provided me with invaluable