Black, Brown and Beige

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAMU 20160316-1 – DUKE ELLINGTON 2 (Výběr Z Nahrávek)

JAMU 20160316-1 – DUKE ELLINGTON 2 (výběr z nahrávek) C D 2 – 1 9 4 0 – 1 9 6 9 12. Take the ‘A’ Train (Billy Strayhorn) 2:55 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra: Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Rex Stewart-co; Joe Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Barney Bigard-cl; Johnny Hodges-cl, ss, as; Otto Hardwick-as, bsx; Harry Carney-cl, as, bs; Ben Webster-ts; Billy Strayhorn-p; Fred Guy-g; Jimmy Blanton-b; Sonny Greer-dr. Hollywood, February 15, 1941. Victor 27380/055283-1. CD Giants of Jazz 53046. 11. Pitter Panther Patter (Duke Ellington) 3:01 Duke Ellington-p; Jimmy Blanton-b. Chicago, October 1, 1940. Victor 27221/053504-2. CD Giants of Jazz 53048. 13. I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good) (Duke Ellington-Paul Francis Webster) 3:21 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra (same personnel); Ivie Anderson-voc. Hollywood, June 26, 1941. Victor 17531 /061319-1. CD Giants of Jazz 53046. 14. The Star Spangled Banner (Francis Scott Key) 1:16 15. Black [from Black, Brown and Beige] (Duke Ellington) 3:57 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra: Rex Stewart, Harold Baker, Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Tricky Sam Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Johnny Hodges, Ben Webster, Harry Carney, Otto Hardwicke, Chauncey Haughton-reeds; Duke Ellington-p; Fred Guy-g; Junior Raglin-b; Sonny Greer-dr. Carnegie Hall, NY, January 23, 1943. LP Prestige P 34004/CD Prestige 2PCD-34004-2. Black, Brown and Beige [four selections] (Duke Ellington) 16. Work Song 4:35 17. -

Johnny Hodges: an Analysis and Study of His Improvisational Style Through Selected Transcriptions

HILL, AARON D., D.M.A. Johnny Hodges: An Analysis and Study of His Improvisational Style Through Selected Transcriptions. (2021) Directed by Dr. Steven Stusek. 82 pp This document investigates the improvisational style of Johnny Hodges based on improvised solos selected from a broad swath of his recording career. Hodges is widely considered one of the foundational voices of the alto saxophone, and yet there are no comprehensive studies of his style. This study includes the analysis of four solos recorded between 1928 and 1962 which have been divided into the categories of blues, swing, and ballads, and his harmonic, rhythmic, and affective tendencies will be discussed. Hodges’ harmonic approach regularly balanced diatonicism with the accentuation of locally significant non-diatonic tones, and his improvisations frequently relied on ornamentation of the melody. He demonstrated considerable rhythmic fluidity in terms of swing, polyrhythmic, and double time feel. The most individually identifiable quality of his style was his frequent and often exaggerated use of affectations, such as scoops, sighs, and glissandi. The resulting body of research highlights the identifiable characteristics of Hodges’ style, and it provides both musical and historical contributions to the scholarship. JOHNNY HODGES: AN ANALYSIS AND STUDY OF HIS IMPROVISATIONAL STYLE THROUGH SELECTED TRANSCRIPTIONS by Aaron D. Hill A Dissertation Submitted to The Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2021 Approved by __________________________________ Committee Chair 2 APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation written by AARON D. HILL has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Duke Ellington-Bubber Miley) 2:54 Duke Ellington and His Kentucky Club Orchestra

MUNI 20070315 DUKE ELLINGTON C D 1 1. East St.Louis Toodle-Oo (Duke Ellington-Bubber Miley) 2:54 Duke Ellington and his Kentucky Club Orchestra. NY, November 29, 1926. 2. Creole Love Call (Duke Ellington-Rudy Jackson-Bubber Miley) 3:14 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, October 26, 1927. 3. Harlem River Quiver [Brown Berries] (Jimmy McHugh-Dorothy Fields-Danni Healy) Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, December 19, 1927. 2:48 4. Tiger Rag [Part 1] (Nick LaRocca) 2:52 5. Tiger Rag [Part 2] 2:54 The Jungle Band. NY, January 8, 1929. 6. A Nite at the Cotton Club 8:21 Cotton Club Stomp (Duke Ellington-Johnny Hodges-Harry Carney) Misty Mornin’ (Duke Ellington-Arthur Whetsol) Goin’ to Town (D.Ellington-B.Miley) Interlude Freeze and Melt (Jimmy McHugh-Dorothy Fields) Duke Ellington and his Cotton Club Orchestra. NY, April 12, 1929. 7. Dreamy Blues [Mood Indigo ] (Albany Bigard-Duke Ellington-Irving Mills) 2:54 The Jungle Band. NY, October 17, 1930. 8. Creole Rhapsody (Duke Ellington) 8:29 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. Camden, New Jersey, June 11, 1931. 9. It Don’t Mean a Thing [If It Ain’t Got That Swing] (D.Ellington-I.Mills) 3:12 Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra. NY, February 2, 1932. 10. Ellington Medley I 7:45 Mood Indigo (Barney Bigard-Duke Ellington-Irving Mills) Hot and Bothered (Duke Ellington) Creole Love Call (Duke Ellington) Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, February 3, 1932. 11. Sophisticated Lady (Duke Ellington-Irving Mills-Mitchell Parish) 3:44 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. -

Beige Adipose Tissue Activities in Human Obesity

International Journal of Obesity (2015) 39, 1515–1522 © 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0307-0565/15 www.nature.com/ijo ORIGINAL ARTICLE Distinct regulation of hypothalamic and brown/beige adipose tissue activities in human obesity B Rachid1, S van de Sande-Lee1, S Rodovalho1, F Folli2, GC Beltramini3, J Morari1, BJ Amorim4, T Pedro5, AF Ramalho1, B Bombassaro1, AJ Tincani6, E Chaim6, JC Pareja6,7, B Geloneze7, CD Ramos4, F Cendes5, MJA Saad8 and LA Velloso1 BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES: The identification of brown/beige adipose tissue in adult humans has motivated the search for methods aimed at increasing its thermogenic activity as an approach to treat obesity. In rodents, the brown adipose tissue is under the control of sympathetic signals originating in the hypothalamus. However, the putative connection between the depots of brown/beige adipocytes and the hypothalamus in humans has never been explored. The objective of this study was to evaluate the response of the hypothalamus and brown/beige adipose tissue to cold stimulus in obese subjects undergoing body mass reduction following gastric bypass. SUBJECTS/METHODS: We evaluated twelve obese, non-diabetic subjects undergoing Roux-in-Y gastric bypass and 12 lean controls. Obese subjects were evaluated before and approximately 8 months after gastric bypass. Lean subjects were evaluated only at admission. Subjects were evaluated for hypothalamic activity in response to cold by functional magnetic resonance, whereas brown/beige adipose tissue activity was evaluated using a (F 18) fluorodeoxyglucose positron emisson tomography/ computed tomography scan and real-time PCR measurement of signature genes. RESULTS: Body mass reduction resulted in a significant increase in brown/beige adipose tissue activity in response to cold; however, no change in cold-induced hypothalamic activity was observed after body mass reduction. -

JAMU 20141112-2 – Duke Ellington: BLACK, BROWN and BEIGE (1943, 1958, 1965-71)

JAMU 20141112-2 – Duke Ellington: BLACK, BROWN AND BEIGE (1943, 1958, 1965-71) Carnegie Hall, New York City, January 23, 1943: 1. Black 20:44 2. Brown 10:10 3. Beige 13:29 Rex Stewart, Harold Baker, Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Tricky Sam Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Johnny Hodges, Ben Webster, Harry Carney, Otto Hardwicke, Chauncey Haughton-reeds; Duke Ellington-p; Fred Guy-g; Junior Raglin-b; Sonny Greer-dr; Betty Roche-voc; Billy Strayhorn-assistant arranger. LP Prestige P-34004 (1977) / CD Prestige 2PCD-34004-2 (1991) Columbia Studios, New York City, February 4, 11 & 12, 1958: 1. Part I 8:17 2. Part II 6:14 3. Part III (Light) 6:26 4. Part IV (Come Sunday) 7:58 5. Part V (Come Sunday) 3:46 6. Part VI (23rd Psalm) 3:01 (plus 10 bonus tracks on CD reissue) Cat Anderson, Harold Baker, Clark Terry-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Quentin Jackson, Britt Woodman-tb; John Sanders-vtb; Jimmy Hamilton-cl; Russell Procope-cl, as; Bill Graham-as; Paul Gonsalves-ts; Harry Carney-bs; Duke Ellington-p; Jimmy Woode-b; Sam Woodyard-dr; Mahalia Jackson-voc. LP Columbia CS 8015 (1958) / CD Columbia/Legacy CK 65566 (1999) New York, March 4, 1965 & May 6, 1971; Chicago, March 31, 1965 & May 18, 1965: 1. Black 8:09 2. Comes Sunday 5:59 3. Light 6:29 4. West Indian Dance 2:15 5. Emancipation Celebration 2:36 6. The Blues 5:23 7. Cy Runs Rock Waltz 2:18 8. Beige 2:24 9. -

ELLINGTON '2000 - by Roger Boyes

TH THE INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN22 year of publication OEMSDUKE ELLINGTON MUSIC SOCIETY | FOUNDER: BENNY AASLAND HONORARY MEMBER: FATHER JOHN GARCIA GENSEL As a DEMS member you'll get access from time to time to / jj£*V:Y WL uni < jue Duke material. Please bear in mind that such _ 2000_ 2 material is to be \ handled with care and common sense.lt " AUQUSl ^^ jj# nust: under no circumstances be used for commercial JUriG w «• ; j y i j p u r p o s e s . As a DEMS member please help see to that this Editor : Sjef Hoefsmit ; simple rule is we \&! : T NSSESgf followed. Thus will be able to continue Assisted by: Roger Boyes ^ fueur special offers lil^ W * - DEMS is a non-profit organization, depending on ' J voluntary offered assistance in time and material. ALL FOR THE L O V E D U K E !* O F Sponsors are welcomed. Address: Voort 18b, Meerle. Belgium - Telephone and Fax: +32 3 315 75 83 - E-mail: [email protected] LOS ANGELES ELLINGTON '2000 - By Roger Boyes The eighteenth international conference of the Kenny struck something of a sombre note, observing that Duke Ellington Study Group took place in the we’re all getting older, and urging on us the need for active effort Roosevelt Hotel, 7000 Hollywood Boulevard, Los to attract the younger recruits who will come after us. Angeles, from Wednesday to Sunday, 24-28 May This report isn't the place for pondering the future of either 2000. The Duke Ellington Society of Southern conferences or the wider activities of the Ellington Study Groups California were our hosts, and congratulations are due around the world. -

John Cornelius Hodges “Johnny” “Rabbit”

1 The ALTOSAX and SOPRANOSAX of JOHN CORNELIUS HODGES “JOHNNY” “RABBIT” Solographers: Jan Evensmo & Ulf Renberg Last update: Aug. 1, 2014, June 5, 2021 2 Born: Cambridge, Massachusetts, July 25, 1906 Died: NYC. May 11, 1970 Introduction: When I joined the Oslo Jazz Circle back in 1950s, there were in fact only three altosaxophonists who really mattered: Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges and Charlie Parker (in alphabetical order). JH’s playing with Duke Ellington, as well as numerous swing recording sessions made an unforgettable impression on me and my friends. It is time to go through his works and organize a solography! Early history: Played drums and piano, then sax at the age of 14; through his sister, he got to know Sidney Bechet, who gave him lessons. He followed Bechet in Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith’s quartet at the Rhythm Club (ca. 1924), then played with Bechet at the Club Basha (1925). Continued to live in Boston during the mid -1920s, travelling to New York for week-end ‘gigs’. Played with Bobby Sawyer (ca. 1925) and Lloyd Scott (ca. 1926), then from late 1926 worked regularly with Chick webb at Paddock Club, Savoy Ballroom, etc. Briefly with Luckey Roberts’ orchestra, then joined Duke Ellington in May 1928. With Duke until March 1951 when formed own small band (ref. John Chilton). Message: No jazz topic has been studied by more people and more systematically than Duke Ellington. So much has been written, culminating with Luciano Massagli & Giovanni M. Volonte: “The New Desor – An updated edition of Duke Ellington’s Story on Records 1924 – 1974”. -

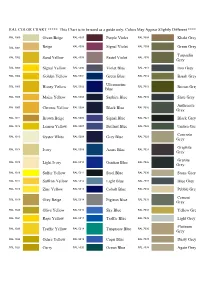

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

The Descending Diminished 7Ths in the Brass in the Intro

VCFA TALK ON ELLINGTON COMPOSITION TECHNIQUES FEB.2017 A.JAFFE 1.) Clarinet Lament [1936] (New Orleans references) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FS92-mCewJ4 (3:14) Compositional Techniques: ABC ‘dialectical’ Sonata/Allegro type of form; where C = elements of A + B combined; Diminution (the way in which the “Basin St. Blues” chord progression is presented in shorter rhythmic values each time it appears); play chord progression Quoting with a purpose (aka ‘signifying’ – see also Henry Louis Gates) 2.) Lightnin’ [1932] (‘Chorus’ form); reliance on distinctively individual voices (like “Tricky Sam” Nanton on trombone) – importance of the compositional uses of such voices who were acquired by Duke by accretion were an important element of his ‘sonic signature’ – the opposite of classical music where sonic conformity in sound is more the rule in choosing players for ensembles. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XlcWbmQYmA (3:07) Techniques: It’s all about the minor third (see also discussion of “Tone Parallel to Harlem”) Motivic Development (in this case the minor 3rd; both harmonically and melodically pervasive) The descending diminished 7ths in the Brass in the Intro: The ascending minor third motif of the theme: The extended (“b9”) background harmony in the Saxophones, reiterating the diminished 7th chord from the introduction: Harmonic AND melodic implications of the motif Early use of the octatonic scale (implied at the modulation -- @ 2:29): Delay of resolution to the tonic chord until ms. 31 of 32 bar form (prefigures Monk, “Ask Me Now”, among others, but decades earlier). 3.) KoKo [1940]; A tour de force of motivic development, in this case rhythmic; speculated to be related to Beethoven’s 5th (Rattenbury, p. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Duke Ellington's Sophisticated Ladies

study guide contents The Play Meet the “Duke” Cotton Club Harlem Renaissance Jazz Music The U Street Connection Musical Revue Dancing Brothers Additional Resources the play Duke Ellington’s Sophisticated Ladies is a musical revue set during America’s Big Band Era (1920-1945). Every song tells a story, and together they paint a colorful pic- ture of Duke Ellington’s life and career as a musician, composer and band leader. Duke Ellington’s Act I highlights the Duke’s early days on tour, while Sophisticated Act II offers a glimpse into his private life and his often Ladies troubled relationships with women. Now Playing at the Lincoln Theatre April 9 – May 30, 2010 Concept by Donald McKayle Based on the music of Duke Ellington Musical and dance arrangements by Lloyd Mayers Vocal arrangements by Malcolm Dodds and Lloyd Mayers Original music direction by Mercer Ellington Directed by Charles Randolph-Wright Choreographed by Maurice Hines meet the “Duke” Harlem Renaissance “His music sounds “Drop me off in Harlem — any place in Harlem. like America.” There’s someone waiting there who makes – Wynton Marsalis it seem like heaven up in Harlem.” dward Kennedy rom the mid-1920s until the early 1930s, the African-American community “Duke” Ellington was in Harlem enjoyed a surging period of cultural, creative and artistic growth. born in Washington, Spurred by an emerging African-American middle class and the freedom D.C. on April 29, after slavery, the Harlem Renaissance began as a literary movement. Authors 1899.E He began playing the Fsuch as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston expressed the spirit of African- piano at age 7, and by 15, Americans and shed light on the black experience.