1945 March 26-April 1 Bloody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaii Waimea Valley B-1 MCCS & SM&SP B-2 Driving Regs B-3 Menu B-5 Word to Pass B-7 Great Aloha Run C-1 Sports Briefs C-2 the Bottom Line C-3

INSIDE National Anthem A-2 2/3 Air Drop A-3 Recruiting Duty A-6 Hawaii Waimea Valley B-1 MCCS & SM&SP B-2 Driving Regs B-3 Menu B-5 Word to Pass B-7 Great Aloha Run C-1 Sports Briefs C-2 The Bottom Line C-3 High School Cadets D-1 MVMOLUME 35, NUMBER 8 ARINEARINEWWW.MCBH.USMC.MIL FEBRUARY 25, 2005 3/3 helps secure clinic Marines maintain security, enable Afghan citizens to receive medical treatment Capt. Juanita Chang Combined Joint Task Force 76 KHOST PROVINCE, Afghanistan — Nearly 1,000 people came to Khilbasat village to see if the announcements they heard over a loud speaker were true. They heard broadcasts that coalition forces would be providing free medical care for local residents. Neither they, nor some of the coalition soldiers, could believe what they saw. “The people are really happy that Americans are here today,” said a local boy in broken English, talking from over a stone wall to a Marine who was pulling guard duty. “I am from a third-world country, but this was very shocking for me to see,” said Spc. Thia T. Valenzuela, who moved to the United States from Guyana in 2001, joined the United States Army the same year, and now calls Decatur, Ga., home. “While I was de-worming them I was looking at their teeth. They were all rotten and so unhealthy,” said Valenzuela, a dental assistant from Company C, 725th Main Support Battalion stationed out of Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. “It was so shocking to see all the children not wearing shoes,” Valenzuela said, this being her first time out of the secure military facility, or “outside the wire” as service members in Afghanistan refer to it. -

Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, 1885-1962

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700873 No online items Register of the Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, 1885-1962 Processed by Don Walker; machine-readable finding aid created by Don Walker Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections University Library, University of the Pacific Stockton, CA 95211 Phone: (209) 946-2404 Fax: (209) 946-2810 URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Library/Find/Holt-Atherton-Special-Collections.html © 1998 University of the Pacific. All rights reserved. Register of the Nimitz (Chester Mss144 1 W.) Collection, 1885-1962 Register of the Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, 1885-1962 Collection number: Mss144 Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections University Library University of the Pacific Contact Information Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections University Library, University of the Pacific Stockton, CA 95211 Phone: (209) 946-2404 Fax: (209) 946-2810 URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Library/Find/Holt-Atherton-Special-Collections.html Processed by: Don Walker Date Completed: August 1998 Encoded by: Don Walker © 1998 University of the Pacific. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, Date (inclusive): 1885-1962 Collection number: Mss144 Creator: Extent: 0.5 linear ft. Repository: University of the Pacific. Library. Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections Stockton, CA 95211 Shelf location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the library's online catalog. Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, Mss144, Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library Biography Chester William Nimitz (1885-1966) was Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. -

Aa000343.Pdf (12.91Mb)

COMFORT SHOE New Style! New Comfort! Haband’s LOW 99 PRICE: per pair 29Roomy new box toe and all the Dr. Scholl’s wonderful comfort your feet are used to, now with handsome new “D-Ring” MagicCling™ closure that is so easy to “touch and go.” Soft supple uppers are genuine leather with durable man-made counter, quarter & trim. Easy-on Fully padded foam-backed linings Easy-off throughout, even on collar, tongue & Magic Cling™ strap, cradle & cushion your feet. strap! Get comfort you can count on, with no buckles, laces or ties, just one simple flick of the MagicCling™ strap and you’re set! Order now! Tan Duke Habernickel, Pres. 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. Peckville, PA 18452 White Black Medium & Wide Widths! per pair ORDER 99 Brown FREE Postage! HERE! Imported Walking Shoes 292 for 55.40 3 for 80.75 Haband 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. 1 1 D Widths: 77⁄2 88⁄2 9 Molded heel cup Peckville, Pennsylvania 18452 1 1 NEW! 9 ⁄2 10 10 ⁄2 11 12 13 14 with latex pad COMFORT INSOLE Send ____ shoes. I enclose $_______ EEE Widths: positions foot and 1 1 purchase price plus $6.95 toward 88⁄2 9 9 ⁄2 Perforated sock and insole 1 adds extra layer 10 10 ⁄2 11 12 13 14 for breathability, postage. of cushioning GA residents FREE POSTAGE! NO EXTRA CHARGE for EEE! flexibility & add sales tax EVA heel insert for comfort 7TY–46102 WHAT WHAT HOW shock-absorption Check SIZE? WIDTH? MANY? 02 TAN TPR outsole 09 WHITE for lightweight 04 BROWN comfort 01 BLACK ® Modular System Card # _________________________________________Exp.: ______/_____ for cushioned comfort Mr./Mrs./Ms._____________________________________________________ ©2004 Schering-Plough HealthCare Products, Inc. -

79-Years Ago on December 7, 1941 Japan Attacks Pearl Harbor, Hawaii

The December 7, 2020 American Indian Tribal79 -NewsYears * Ernie Ago C. Salgado on December Jr.,CE0, Publisher/Editor 7, 1941 Japan Attacks Pearl Harbor, Hawaii America Entered World War II 85-90 Million People Died WW II Ended - Germany May 8, 1945 & Japan, September 2, 1945 All the Nations involved in the war threw and a majority of it has never been recovered. Should the Voter Fraud succeed in America their entire economic, industrial, and scien- Japan, which aimed to dominate Asia and the and the Democratic Socialist Party win the tific capabilities behind the war effort, blur- 2020 Presidential election we will become Pacific, was at war with China by 1937. ring the distinction between civilian and mili- Germany 1933. World War II is generally said to have begun tary resources. on 1 September 1939, with the invasion of And like Hitler’s propaganda news the main World War II was the deadliest conflict in hu- Poland by Germany and subsequent declara- stream media and the Big Tech social media man history, marked by 85 to 90 million fatal- tions of war on Germany by France and the fill that role. ities, most of whom were civilians in the So- United Kingdom. We already have political correctness which is viet Union and China. From late 1939 to early 1941, in a series of anti-free speech, universities and colleges that It included massacres, the genocide of the campaigns and treaties, Germany conquered prohibit free speech, gun control, judges that Jews which is known as the Holocaust, strate- or controlled much of continental Europe, and make up their own laws, we allow the mur- gic bombing, premeditated death from starva- formed alliance with Italy and Japan. -

C H a P T E R 25 World War II

NASH.7654.CP25p826-861.vpdf 9/23/05 3:35 PM Page 826 CHAPTER 25 World War II This World War II poster depicts the many nations united in the fight against the Axis powers. In reality there were often disagreements. Notice that to the right, the American sailor is marching next to Chinese and Soviet soldiers. Within a few years after victory, they would be enemies. (University of Georgia Libraries, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library) American Stories A Native American Boy Plays at War N. Scott Momaday, a Kiowa Indian born in Lawton, Oklahoma, in 1934, grew up on Navajo,Apache, and Pueblo reservations. He was only 11 years old when World War II ended, yet the war had changed his life. Shortly after the United States entered the war, Momaday’s parents moved to New Mexico, where his father got a job with an oil company and his mother worked in the civilian personnel office at an army air force 826 NASH.7654.CP25p826-861.vpdf 9/23/05 3:35 PM Page 827 CHAPTER OUTLINE base. Like many couples, they had struggled through the hard times of the Depression. The Twisting Road to War The war meant jobs. Foreign Policy in a Global Age Momaday’s best friend was Billy Don Johnson, a “reddish, robust boy of great good Europe on the Brink of War humor and intense loyalty.” Together they played war, digging trenches and dragging Ethiopia and Spain themselves through imaginary minefields. They hurled grenades and fired endless War in Europe rounds from their imaginary machine guns, pausing only to drink Kool-Aid from their The Election of 1940 canteens.At school, they were taught history and math and also how to hate the enemy Lend-Lease and be proud of America. -

Dedication Marine Corps War Memorial

• cf1 d>fu.cia[ CJI'zank 'Jjou. {tom tf'u. ~ou.1.fey 'Jou.ndation and c/ll( onumE.nt f]:)E.di catio n eMu. §oldie. ~~u.dey 9Jtle£: 9-o't Con9u~ma.n. ..£a.uy J. dfopkira and .:Eta(( Captain §ayfc. df. cf?u~c., r"Unitc.d 2,'tat~ dVaay cf?unac. c/?e.tiud g:>. 9 . C. '3-t.ank.fin c.Runyon aow.fc.y Captain ell. <W Jonu, Comm.andtn.9 D((kn, r"U.cS.a. !lwo Jima ru. a. o«. c. cR. ..£ie.utenaJZI: Coforuf c.Richa.t.d df. Jetl, !J(c.ntucky cflit dVa.tionaf §uat.d ..£ieuienant C!ofond Jarnu df. cJU.affoy, !J(wtucky dVa.tional §uat.d dU.ajo"< dtephen ...£. .::Shivc.u r"Unit£d c:Sta.tu dU.a.t.in£ Cotp~ :Jfu. fln~pul:ot.- fl~huclot. c:Sta.{{. 11/: cJU.. P.C.D., £:ci.n9ton., !J(!:J· dU.a1tn c:Sc.1.9c.a.nt ...La.ny dU.a.'ltin, r"Unltc.d c:Stal£~ dU.a.t.lnc. Cot.pi cR£UW£ £xi1t9ton §t.anite Company, dU.t.. :Daniel :be dU.at.cUJ (Dwnc.t.} !Pa.t.li dU.onurncn.t <Wot.ki, dU.t. Jim dfifk.e (Dwn£"tj 'Jh£ dfonowbf£ Duf.c.t. ~( !J(£ntucky Cofone£. <l/. 9. <W Pof.t dVo. 1834, dU.t.. <Wiffu df/{~;[ton /Po1l Commarzdz.t} dU.t.. Jarnu cJU.. 9inch Jt.. dU.t.. Jimmy 9tn.ch. dU.u. dVo/J[~; cflnow1m£th dU.u. 'Je.d c:Suffiva.n dU.t.. ~c. c/?odt.'9uc.z d(,h. -

Native Americans and World War II

Reemergence of the “Vanishing Americans” - Native Americans and World War II “War Department officials maintained that if the entire population had enlisted in the same proportion as Indians, the response would have rendered Selective Service unnecessary.” – Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan Overview During World War II, all Americans banded together to help defeat the Axis powers. In this lesson, students will learn about the various contributions and sacrifices made by Native Americans during and after World War II. After learning the Native American response to the attack on Pearl Harbor via a PowerPoint centered discussion, students will complete a jigsaw activity where they learn about various aspects of the Native American experience during and after the war. The lesson culminates with students creating a commemorative currency honoring the contributions and sacrifices of Native Americans during and after World War II. Grade 11 NC Essential Standards for American History II • AH2.H.3.2 - Explain how environmental, cultural and economic factors influenced the patterns of migration and settlement within the United States since the end of Reconstruction • AH2.H.3.3 - Explain the roles of various racial and ethnic groups in settlement and expansion since Reconstruction and the consequences for those groups • AH2.H.4.1 - Analyze the political issues and conflicts that impacted the United States since Reconstruction and the compromises that resulted • AH2.H.7.1 - Explain the impact of wars on American politics since Reconstruction • AH2.H.7.3 - Explain the impact of wars on American society and culture since Reconstruction • AH2.H.8.3 - Evaluate the extent to which a variety of groups and individuals have had opportunity to attain their perception of the “American Dream” since Reconstruction Materials • Cracking the Code handout, attached (p. -

Closingin.Pdf

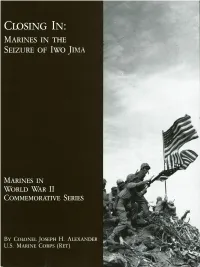

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 156 WASHINGTON, SATURDAY, MARCH 20, 2010 No. 42 Senate The Senate was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Monday, March 22, 2010, at 2 p.m. House of Representatives SATURDAY, MARCH 20, 2010 The House met at 9 a.m. and was Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- HEALTH CARE REFORM called to order by the Speaker pro tem- nal stands approved. (Ms. SCHWARTZ asked and was pore (Ms. CLARKE). Mr. KLEIN of Florida. Madam Speak- given permission to address the House f er, pursuant to clause 1, rule I, I de- for 1 minute and to revise and extend mand a vote on agreeing to the Speak- DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER her remarks.) er’s approval of the Journal. PRO TEMPORE Ms. SCHWARTZ. Today we are close The SPEAKER pro tempore. The to achieving a long-sought goal ensur- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- question is on the Speaker’s approval ing that all Americans have access to fore the House the following commu- of the Journal. meaningful, affordable health cov- nication from the Speaker: The question was taken; and the erage. Passing health care reform bene- WASHINGTON, DC, Speaker pro tempore announced that fits all of us: families, seniors, busi- March 20, 2010. the ayes appeared to have it. nesses, taxpayers, and our Nation. I hereby appoint the Honorable YVETTE D. Mr. KLEIN of Florida. -

Two US Navy's Submarines

Now available to the public by subscription. See Page 63 Volume 2018 2nd Quarter American $6.00 Submariner Special Election Issue USS Thresher (SSN-593) America’s two nuclear boats on Eternal Patrol USS Scorpion (SSN-589) More information on page 20 Download your American Submariner Electronically - Same great magazine, available earlier. Send an E-mail to [email protected] requesting the change. ISBN List 978-0-9896015-0-4 American Submariner Page 2 - American Submariner Volume 2018 - Issue 2 Page 3 Table of Contents Page Number Article 3 Table of Contents, Deadlines for Submission 4 USSVI National Officers 6 Selected USSVI . Contacts and Committees AMERICAN 6 Veterans Affairs Service Officer 6 Message from the Chaplain SUBMARINER 7 District and Base News This Official Magazine of the United 7 (change of pace) John and Jim States Submarine Veterans Inc. is 8 USSVI Regions and Districts published quarterly by USSVI. 9 Why is a Ship Called a She? United States Submarine Veterans Inc. 9 Then and Now is a non-profit 501 (C) (19) corporation 10 More Base News in the State of Connecticut. 11 Does Anybody Know . 11 “How I See It” Message from the Editor National Editor 12 2017 Awards Selections Chuck Emmett 13 “A Guardian Angel with Dolphins” 7011 W. Risner Rd. 14 Letters to the Editor Glendale, AZ 85308 18 Shipmate Honored Posthumously . (623) 455-8999 20 Scorpion and Thresher - (Our “Nuclears” on EP) [email protected] 22 Change of Command Assistant Editor 23 . Our Brother 24 A Boat Sailor . 100-Year Life Bob Farris (315) 529-9756 26 Election 2018: Bios [email protected] 41 2018 OFFICIAL BALLOT 43 …Presence of a Higher Power Assoc. -

Americanlegionvo1356amer.Pdf (9.111Mb)

Executive Dres WINTER SLACKS -|Q95* i JK_ J-^ pair GOOD LOOKING ... and WARM ! Shovel your driveway on a bitter cold morning, then drive straight to the office! Haband's impeccably tailored dress slacks do it all thanks to these great features: • The same permanent press gabardine polyester as our regular Dress Slacks. • 1 00% preshrunk cotton flannel lining throughout. Stitched in to stay put! • Two button-thru security back pockets! • Razor sharp crease and hemmed bottoms! • Extra comfortable gentlemen's full cut! • 1 00% home machine wash & dry easy care! Feel TOASTY WARM and COMFORTABLE! A quality Haband import Order today! Flannel 1 i 95* 1( 2 for 39.50 3 for .59.00 I 194 for 78. .50 I Haband 100 Fairview Ave. Prospect Park, NJ 07530 Send REGULAR WAISTS 30 32 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 pairs •BIG MEN'S ADD $2.50 per pair for 46 48 50 52 54 INSEAMS S( 27-28 M( 29-30) L( 31-32) XL( 33-34) of pants ) I enclose WHAT WHAT HOW 7A9.0FL SIZE? INSEAM7 MANY? c GREY purchase price D BLACK plus $2.95 E BROWN postage and J SLATE handling. Check Enclosed a VISA CARD# Name Mail Address Apt. #_ City State .Zip_ 00% Satisfaction Guaranteed or Full Refund of Purchase $ § 3 Price at Any Time! The Magazine for a Strong America Vol. 135, No. 6 December 1993 ARTICLE s VA CAN'T SURVIVE BY STANDING STILL National Commander Thiesen tells Congress that VA will have to compete under the President's health-care plan. -

THE GRUNT the Lakeland Grunt, PO Box 0008, Pompton Lakes, NJ 07442 April 2014 March 2015 Mike Mcnulty –Editor 732-213-5264

Lakeland Detachment #744 THE GRUNT The Lakeland Grunt, PO Box 0008, Pompton Lakes, NJ 07442 April 2014 March 2015 Mike McNulty –Editor 732-213-5264 Your Officers for 2015 Commandants Corner Charles Huha-Commandant 973-835-2315 [email protected] Michael McNulty—Sr. Vice 732-213-5264 Marine Corps League [email protected] Lakeland Detachment—744 Kevin O’Leary -Jr. Vice 201-644-8078 March 2015 [email protected] On February 18, 2015, Detachment member Dave Peter Alvarez—Paymaster/Adj 973-839-5693 Elshout and I had the distinct pleasure of having din- [email protected] ner with a Marine giant, Zigmund “Ziggy” Gasiewicz. We joined Ziggy, his son Peter, Nephew, Louis, both Paul Thompson Service Officer 201-651-1822 Marines, and other family members and Marines for [email protected] a wonderful night of sharing and being with a legend, Ray Sears– Judge Advocate 973-694-8457 up close and personal. Ziggy will be 94 in July. He [email protected] joined the Marine Corps in 1940 while still a teenag- er. After Parris Island, he served at Guantanamo Theresa Muttel– Secretary 973-764-9565 Bay and did practice assaults in the islands off of [email protected] Puerto Rico. After Pearl Harbor, he was sent to Cali- fornia for training, then to New Zealand and the Fiji Bill De Lorenzo—Legal Officer 201-337-6677 Islands for more training. His ultimate destination [email protected] was Guadalcanal. Dennis Kievit—Chaplain 201-825-0183 Ziggy hit Guadalcanal as a 75 mil pack Howitzer ar- [email protected] tillery man.