Articles (1969-1997)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Open Space and Recreation Plan

2015 OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN City of Melrose Office of Planning & Community Development City of Melrose Open Space and Recreation Plan Table of Contents Table of Contents Section 1: Plan Summary ............................................................................................................. 1-1 Section 2: Introduction ................................................................................................................. 2-1 A. Statement of Purpose ........................................................................................................... 2-1 B. Planning Process and Public Participation .......................................................................... 2-1 C. Accomplishments ................................................................................................................ 2-2 Section 3: Community Setting ..................................................................................................... 3-1 A. Regional Context ................................................................................................................. 3-1 B. History of the Community ................................................................................................... 3-3 C. Population Characteristics ................................................................................................... 3-4 D. Growth and Development Patterns ...................................................................................... 3-9 Section 4: Environmental Inventory and Analysis -

From Flags of Our Fathers to Letters from Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood's Balancing of Japanese and American Perspectives

Volume 4 | Issue 12 | Article ID 2290 | Dec 02, 2006 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus From Flags of Our Fathers to Letters From Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood's Balancing of Japanese and American Perspectives Aaron Gerow From Flags of Our Fathers to Letters From Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood’s Balancing of Japanese and American Perspectives By Aaron Gerow History, like the cinema, can often be a matter of perspective. That’s why Clint Eastwood’s decision to narrate the Battle of Iwo Jima from both the American and the Japanese point of view is not really new; it had been done before in Tora Tora Tora (1970), for instance. But by dividing these perspectives in different films directed at Japanese and international audiences, Eastwood makes history not merely an issue of which side you are on, but of how to look at history itself. Flags of Our Fathers, the American version, is less about the battle than the memory of war, focusing in particular on how nations compulsively create heroes when they need them (like with the soldiers who raised the flag on Iwo Jima) and forget them later when they don’t. Instead of giving the national narrative of bravery in capturing Iwo Jima, the film shows how such stories are manufactured by media and governments to further the aims of the country, whatever may be the truth or the 1 4 | 12 | 0 APJ | JF feelings of the individual soldiers. Against the And some of the figures are fascinating. constructed nature of public heroism, Eastwood Kuribayashi (Watanabe Ken) had studied in the poses the private real bonds between men; United States, wrote loving letters to his son against public memory he focuses on personal with comic illustrations, and protected his men trauma. -

An Interview with Stuart H. Shiffman Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission

An Interview with Stuart H. Shiffman Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission Stuart H. Shiffman worked in the Attorney General’s office, opinions division, from 1974-75, the Sangamon County State’s Attorney’s office from 1975-79, returned to the Attorney General’s office, this time in the criminal division, from 1979-80, and then returned to the State’s Attorney’s office from 1980-83. In 1983, he was appointed an Associate Circuit Judge in the 7th Judicial Circuit and served in that capacity until 2006. After his retirement from the judiciary Judge Shiffman worked for the State Appellate Defender and in private practice with the law firm Feldman Wasser. Interview Dates: May 29, 2015, January 16, 2016, and June 14, 2016 Interview Location: Law office of Judge Shiffman, Feldman Wasser, Springfield, Illinois Interview Format: Video Interviewer: Justin Law, Oral Historian, Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission Technical Assistance: Matt Burns, Director of Administration, Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission Transcription: Interview One: Benjamin Belzer, Collections Manager/Research Associate, Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission Interview Two and Three: Ashlee Leach, Transcriptionist, Loveland, Colorado Editing: Justin Law Total pages: Interview One, 58; Interview Two, 84; Interview Three, 69 Total time: Interview One, 02:14:09; Interview Two, 3:00:47; Interview Three, 2:48:12 1 Abstract Stuart H. Shiffman Biographical: Stuart H. Shiffman was born in Chicago, Illinois on March 4, 1948 and spent his early life in Chicago, and later Skokie, Illinois. After graduating from Evanston High School in 1966, he attended and received a degree from Northwestern University in 1970. -

79-Years Ago on December 7, 1941 Japan Attacks Pearl Harbor, Hawaii

The December 7, 2020 American Indian Tribal79 -NewsYears * Ernie Ago C. Salgado on December Jr.,CE0, Publisher/Editor 7, 1941 Japan Attacks Pearl Harbor, Hawaii America Entered World War II 85-90 Million People Died WW II Ended - Germany May 8, 1945 & Japan, September 2, 1945 All the Nations involved in the war threw and a majority of it has never been recovered. Should the Voter Fraud succeed in America their entire economic, industrial, and scien- Japan, which aimed to dominate Asia and the and the Democratic Socialist Party win the tific capabilities behind the war effort, blur- 2020 Presidential election we will become Pacific, was at war with China by 1937. ring the distinction between civilian and mili- Germany 1933. World War II is generally said to have begun tary resources. on 1 September 1939, with the invasion of And like Hitler’s propaganda news the main World War II was the deadliest conflict in hu- Poland by Germany and subsequent declara- stream media and the Big Tech social media man history, marked by 85 to 90 million fatal- tions of war on Germany by France and the fill that role. ities, most of whom were civilians in the So- United Kingdom. We already have political correctness which is viet Union and China. From late 1939 to early 1941, in a series of anti-free speech, universities and colleges that It included massacres, the genocide of the campaigns and treaties, Germany conquered prohibit free speech, gun control, judges that Jews which is known as the Holocaust, strate- or controlled much of continental Europe, and make up their own laws, we allow the mur- gic bombing, premeditated death from starva- formed alliance with Italy and Japan. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

Dedication Marine Corps War Memorial

• cf1 d>fu.cia[ CJI'zank 'Jjou. {tom tf'u. ~ou.1.fey 'Jou.ndation and c/ll( onumE.nt f]:)E.di catio n eMu. §oldie. ~~u.dey 9Jtle£: 9-o't Con9u~ma.n. ..£a.uy J. dfopkira and .:Eta(( Captain §ayfc. df. cf?u~c., r"Unitc.d 2,'tat~ dVaay cf?unac. c/?e.tiud g:>. 9 . C. '3-t.ank.fin c.Runyon aow.fc.y Captain ell. <W Jonu, Comm.andtn.9 D((kn, r"U.cS.a. !lwo Jima ru. a. o«. c. cR. ..£ie.utenaJZI: Coforuf c.Richa.t.d df. Jetl, !J(c.ntucky cflit dVa.tionaf §uat.d ..£ieuienant C!ofond Jarnu df. cJU.affoy, !J(wtucky dVa.tional §uat.d dU.ajo"< dtephen ...£. .::Shivc.u r"Unit£d c:Sta.tu dU.a.t.in£ Cotp~ :Jfu. fln~pul:ot.- fl~huclot. c:Sta.{{. 11/: cJU.. P.C.D., £:ci.n9ton., !J(!:J· dU.a1tn c:Sc.1.9c.a.nt ...La.ny dU.a.'ltin, r"Unltc.d c:Stal£~ dU.a.t.lnc. Cot.pi cR£UW£ £xi1t9ton §t.anite Company, dU.t.. :Daniel :be dU.at.cUJ (Dwnc.t.} !Pa.t.li dU.onurncn.t <Wot.ki, dU.t. Jim dfifk.e (Dwn£"tj 'Jh£ dfonowbf£ Duf.c.t. ~( !J(£ntucky Cofone£. <l/. 9. <W Pof.t dVo. 1834, dU.t.. <Wiffu df/{~;[ton /Po1l Commarzdz.t} dU.t.. Jarnu cJU.. 9inch Jt.. dU.t.. Jimmy 9tn.ch. dU.u. dVo/J[~; cflnow1m£th dU.u. 'Je.d c:Suffiva.n dU.t.. ~c. c/?odt.'9uc.z d(,h. -

Native Americans and World War II

Reemergence of the “Vanishing Americans” - Native Americans and World War II “War Department officials maintained that if the entire population had enlisted in the same proportion as Indians, the response would have rendered Selective Service unnecessary.” – Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan Overview During World War II, all Americans banded together to help defeat the Axis powers. In this lesson, students will learn about the various contributions and sacrifices made by Native Americans during and after World War II. After learning the Native American response to the attack on Pearl Harbor via a PowerPoint centered discussion, students will complete a jigsaw activity where they learn about various aspects of the Native American experience during and after the war. The lesson culminates with students creating a commemorative currency honoring the contributions and sacrifices of Native Americans during and after World War II. Grade 11 NC Essential Standards for American History II • AH2.H.3.2 - Explain how environmental, cultural and economic factors influenced the patterns of migration and settlement within the United States since the end of Reconstruction • AH2.H.3.3 - Explain the roles of various racial and ethnic groups in settlement and expansion since Reconstruction and the consequences for those groups • AH2.H.4.1 - Analyze the political issues and conflicts that impacted the United States since Reconstruction and the compromises that resulted • AH2.H.7.1 - Explain the impact of wars on American politics since Reconstruction • AH2.H.7.3 - Explain the impact of wars on American society and culture since Reconstruction • AH2.H.8.3 - Evaluate the extent to which a variety of groups and individuals have had opportunity to attain their perception of the “American Dream” since Reconstruction Materials • Cracking the Code handout, attached (p. -

Two US Navy's Submarines

Now available to the public by subscription. See Page 63 Volume 2018 2nd Quarter American $6.00 Submariner Special Election Issue USS Thresher (SSN-593) America’s two nuclear boats on Eternal Patrol USS Scorpion (SSN-589) More information on page 20 Download your American Submariner Electronically - Same great magazine, available earlier. Send an E-mail to [email protected] requesting the change. ISBN List 978-0-9896015-0-4 American Submariner Page 2 - American Submariner Volume 2018 - Issue 2 Page 3 Table of Contents Page Number Article 3 Table of Contents, Deadlines for Submission 4 USSVI National Officers 6 Selected USSVI . Contacts and Committees AMERICAN 6 Veterans Affairs Service Officer 6 Message from the Chaplain SUBMARINER 7 District and Base News This Official Magazine of the United 7 (change of pace) John and Jim States Submarine Veterans Inc. is 8 USSVI Regions and Districts published quarterly by USSVI. 9 Why is a Ship Called a She? United States Submarine Veterans Inc. 9 Then and Now is a non-profit 501 (C) (19) corporation 10 More Base News in the State of Connecticut. 11 Does Anybody Know . 11 “How I See It” Message from the Editor National Editor 12 2017 Awards Selections Chuck Emmett 13 “A Guardian Angel with Dolphins” 7011 W. Risner Rd. 14 Letters to the Editor Glendale, AZ 85308 18 Shipmate Honored Posthumously . (623) 455-8999 20 Scorpion and Thresher - (Our “Nuclears” on EP) [email protected] 22 Change of Command Assistant Editor 23 . Our Brother 24 A Boat Sailor . 100-Year Life Bob Farris (315) 529-9756 26 Election 2018: Bios [email protected] 41 2018 OFFICIAL BALLOT 43 …Presence of a Higher Power Assoc. -

Flags of Our Fathers: a Novel by James Bradley with Ron Powers by Spencer Green, Staff Writer

~ ________ Issue ~ http://www.elsegundousd.com/eshs/bayeagle0607/NovembeP25FlagsO... Flags of our Fathers: A Novel by James Bradley with Ron Powers by Spencer Green, Staff Writer “There are no great men. Just great challenges which ordinary men, out of necessity, are forced by circumstances to meet.” Admiral William F. “Bull” Hawlsey's words are the theme of Flags Of Our Fathers. Flags Of Our Fathers is not a book about heroes; instead, it is an account of six ordinary men doing what they had to in order to help their brothers in arms. No doubt, you've seen the picture before: the picture of six men raising a flag over Iwo Jima during World War II. James Bradley and Ron Powers have finally told the story of the six men in this iconic image. Bradley's father, John, is one of these men, one of the flag raisers who became instant heroes once the picture got back to America. While the Marines and Navy personnel continued to fight on Iwo Jima, the image began hitting newsstands around the country. This picture instilled hope in Americans, inspiring a country that was tired of fighting. The figures in the picture became national heroes, despite the fact that half of them were killed in combat soon after the famous picture was taken. Bradley tells the reader of how his father, John "Doc" Bradley, and the two other survivors, Rene Gagnon and Ira Hayes, were forced to go around the country to raise money for the government. This was painful for the three men, as they had been forced to see many of their friends die horribly in battle, and they felt as if their dead and wounded comrades deserved the glory and fame more than them. -

The AFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE in TEMPE

The AFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE in TEMPE The AFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE in TEMPE by Jared Smith A publication of the Tempe History Museum and its African American Advisory Committee Published with a grant from the Arizona Humanities Council Photos courtesy of the Tempe History Museum, unless otherwise noted Cover artwork by Aaron Forney Acknowledgements Like the old saying, “it takes a village to raise a child,” so it went with this booklet to document the African American history of Tempe, Arizona. At the center of this project is the Tempe History Museum’s African American Advisory Group, formed in 2008. The late Edward Smith founded the Advisory Group that year and served as Chair until February 2010. Members of the Advisory Group worked with the staff of the Tempe History Museum to apply for a grant from the Arizona Humanities Council that would pay for the printing costs of the booklet. Advisory Group members Mary Bishop, Dr. Betty Greathouse, Maurice Ward, Earl Oats, Dr. Frederick Warren, and Museum Administrator Dr. Amy Douglass all served on the Review Committee and provided suggestions, feedback, and encouragement for the booklet. Volunteers, interns, staff, and other interested parties provided a large amount of research, editing, formatting, and other help. Dr. Robert Stahl, Chris Mathis, Shelly Dudley, John Tenney, Sally Cole, Michelle Reid, Sonji Muhammad, Sandra Apsey, Nathan Hallam, Joe Nucci, Bryant Monteihl, Cynthia Yanez, Jennifer Sweeney, Bettina Rosenberg, Robert Spindler, Christine Marin, Zack Tomory, Patricia A. Bonn, Andrea Erickson, Erika Holbein, Joshua Roffler, Dan Miller, Aaron Adams, Aaron Monson, Dr. James Burns, and Susan Jensen all made significant contributions to the booklet. -

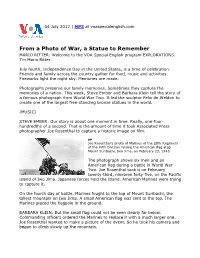

From a Photo of War, a Statue to Remember MARIO RITTER: Welcome to the VOA Special English Program EXPLORATIONS

04 July 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com From a Photo of War, a Statue to Remember MARIO RITTER: Welcome to the VOA Special English program EXPLORATIONS. I’m Mario Ritter. July fourth, Independence Day in the United States, is a time of celebration. Friends and family across the country gather for food, music and activities. Fireworks light the night sky. Memories are made. Photographs preserve our family memories. Sometimes they capture the memories of a nation. This week, Steve Ember and Barbara Klein tell the story of a famous photograph from World War Two. It led the sculptor Felix de Weldon to create one of the largest free-standing bronze statues in the world. (MUSIC) STEVE EMBER: Our story is about one moment in time. Really, one-four- hundredths of a second. That is the amount of time it took Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal to capture a historic image on film. AP Joe Rosenthal's photo of Marines of the 28th Regiment of the Fifth Division raising the American flag atop Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima, on February 23, 1945 The photograph shows six men and an American flag during a battle in World War Two. Joe Rosenthal took it on February twenty-third, nineteen forty-five, on the Pacific island of Iwo Jima. Japanese forces held the island. American Marines were trying to capture it. On the fourth day of battle, Marines fought to the top of Mount Suribachi, the tallest mountain on Iwo Jima. A small American flag was sent to the top. The Marines placed the flagpole in the ground. -

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting.