Changing Transgender Identities in Post-War Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Certified Facilities (Cooking)

List of certified facilities (Cooking) Prefectures Name of Facility Category Municipalities name Location name Kasumigaseki restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Tokyo-club Building,3-2-6,Kasumigaseki,Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Sakura terrace,Iidabashi Grand Bloom,2-10- ALOHA TABLE iidabashi restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 2,Fujimi,Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku banquet kitchen The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 24th floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Peter The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Boutique & Café First basement, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Hei Fung Terrace The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Lobby 1-1-1,Uchisaiwai-cho,Chiyoda-ku TORAYA Imperial Hotel Store restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (Imperial Hotel of Tokyo,Main Building,Basement floor) mihashi First basement, First Avenu Tokyo Station,1-9-1 marunouchi, restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (First Avenu Tokyo Station Store) Chiyoda-ku PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Hot hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku Kitchen,Cold Kitchen) PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Preparation) hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku LE PORC DE VERSAILLES restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First~3rd floor, Florence Kudan, 1-2-7, Kudankita, Chiyoda-ku Kudanshita 8th floor, Yodobashi Akiba Building, 1-1, Kanda-hanaoka-cho, Grand Breton Café -

Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family

Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family by Hiroko Umegaki Lucy Cavendish College Submitted November 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies provided by Apollo View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by 1 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Acknowledgments Without her ever knowing, my grandmother provided the initial inspiration for my research: this thesis is dedicated to her. Little did I appreciate at the time where this line of enquiry would lead me, and I would not have stayed on this path were it not for my family, my husband, children, parents and extended family: thank you. -

Meguro Walking Map

Meguro Walking Map Meguro Walking Map Primary print number No. 31-30 Published February 2, 2020 December 6, 2019 Published by Meguro City Edited by Health Promotion Section, Health Promotion Department; Sports Promotion Section, Culture and Sports Department, Meguro City 2-19-15 Kamimeguro, Meguro City, Tokyo Phone 03-3715-1111 Cooperation provided by Meguro Walking Association Produced by Chuo Geomatics Co., Ltd. Meguro City Total Area Course Map Contents Walking Course 7 Meguro Walking Courses Meguro Walking Course Higashi-Kitazawa Sta. Total Area Course Map C2 Walking 7 Meguro Walking Courses P2 Course 1: Meguro-dori Ave. Ikenoue Sta. Ke Walk dazzling Meguro-dori Ave. P3 io Inok Map ashira Line Komaba-todaimae Sta. Course 2: Komaba/Aobadai area Shinsen Sta. Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji P7 0 100 500 1,000m Awas hima-dori St. 3 Course 3: Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area Kyuyamate-dori Ave. Walk the 1964 Tokyo Olympics P11 2 Komaba/Aobadai area Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji Shibuya City Tamagawa-dori Ave. Course 4: Himon-ya/Meguro-honcho area Ikejiri-ohashi Sta. Meguro/Shimomeguro area Walk among the history and greenery of Himon-ya P15 5 Walk among Edo period townscape Daikan-yama Sta. Course 5: Meguro/Shimomeguro area Tokyu Den-en-toshi Line Walk among Edo period townscape P19 Ebisu Sta. kyo Me e To tro Hibiya Lin Course 6: Yakumo/Midorigaoka area Naka-meguro Sta. J R Walk a green road born from a culvert P23 Y Yutenji/Chuo-cho area a m 7 Yamate-dori Ave. a Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n o Course 7: Yutenji/Chuo-cho area t e L Meguro City Office i Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n P27 e / S 2 a i k Minato e y Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area o in City Small efforts, L Yutenji Sta. -

Outer Loop Oimachi Shonan-Shinjuku Line Omori Kamata Emolga Keihin-Tohoku Line

URL http://www.webmtabi.jp/201208/print/pokemon_yamanote-line_en.pdf 2012.8 >> JR Yamanote Line Outer Tracks Pokemon Stamp Rally 2012 Guide www.webmtabi.jp Secret? Akabane Secret? Higashi-Jujo Oji Kita-Senju Takasaki Line Oku Jujo Kami-Nakazato Tabata Joban Line Black Kyurem Itabashi Nishi-Nippori Minami-Senju Komagome MikawashimaOshawott Ikebukuro Nippori Sugamo Mejiro Ootsuka Uguisudani Goal Ueno Vanillite Takadanobaba Okachimachi Nakano Ichigaya IidabashiSuidobashi White Kyurem Shin-Okubo Higashi-NakanoOkubo Shinanomachi Akihabara Sendagaya Shinjuku Yotsuya Ochanomizu Chuo Line, Sobu Line Chuo Line Kanda Goal Yoyogi Pansage (Local Train) (Limited Express) Tokyo Cryogonal Harajuku Kyurem Yurakucho Shibuya Shimbashi Ebisu Yamanote Line Meguro Hamamatsucho Snivy Gotanda Secret? Tamachi Saikyo Line Shinagawa Osaki Outer loop Oimachi Shonan-Shinjuku Line Omori Kamata Emolga Keihin-Tohoku Line ○○○ ○○○ Goal Stairway Elevator Escalator Station Stamp Desk To Shinagawa Shibuya 2 On board for 2 minutes Car No.11 Door #4 Ticket Gate TOKYO (Kyurem[Kyuremu]) Yamanote Line Yamanote Line Outer Tracks - No.5 Tabata Marunouchi Central Exit Nishi-Nippori Car No.5 Door #1 Nippori To Shinagawa Uguisudani Ueno Shibuya 1 3 5 7 9 11 2 Marunouchi Underground Okachimachi North Exit Akihabara Kanda South Passage Central Passage North Passage Tokyo Yurakucho Shimbashi Hamamatsucho Tamachi Yurakucho Shinagawa ↑ Local Train Rapid Service 2 Keihin-Tohoku Line 1/4 URL http://www.webmtabi.jp/201208/print/pokemon_yamanote-line_en.pdf ○○○ ○○○ Goal Stairway Elevator -

A World Like Ours: Gay Men in Japanese Novels and Films

A WORLD LIKE OURS: GAY MEN IN JAPANESE NOVELS AND FILMS, 1989-2007 by Nicholas James Hall A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Nicholas James Hall, 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines representations of gay men in contemporary Japanese novels and films produced from around the beginning of the 1990s so-called gay boom era to the present day. Although these were produced in Japanese and for the Japanese market, and reflect contemporary Japan’s social, cultural and political milieu, I argue that they not only articulate the concerns and desires of gay men and (other queer people) in Japan, but also that they reflect a transnational global gay culture and identity. The study focuses on the work of current Japanese writers and directors while taking into account a broad, historical view of male-male eroticism in Japan from the Edo era to the present. It addresses such issues as whether there can be said to be a Japanese gay identity; the circulation of gay culture across international borders in the modern period; and issues of representation of gay men in mainstream popular culture products. As has been pointed out by various scholars, many mainstream Japanese representations of LGBT people are troubling, whether because they represent “tourism”—they are made for straight audiences whose pleasure comes from being titillated by watching the exotic Others portrayed in them—or because they are made by and for a female audience and have little connection with the lives and experiences of real gay men, or because they circulate outside Japan and are taken as realistic representations by non-Japanese audiences. -

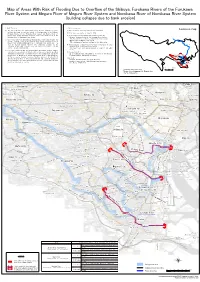

Map of Areas with Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya

Map of Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System (building collapse due to bank erosion) 1. About this map 2. Basic information Location map (1) This map shows the areas where there may be flooding powerful enough to (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government collapse buildings for sections subject to flood warnings of the Shibuya, (2) Risk areas designated on June 27, 2019 Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and those subject to water-level notification of the (3) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System. Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) (2) This river flood risk map shows estimated width of bank erosion along the Meguro River of Meguro River System Shibuya, Furukawa rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System resulting from the maximum assumed rainfall. The simulation is based on the (4) Rivers subject to water-level notification covered by this map Sumida River situation of the river channels and flood control facilities as of the Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System time of the map's publication. (The water-level notification section is shown in the table below.) (3) This river flood risk map (building collapse due to bank erosion) roughly indicates the areas where buildings could collapse or be washed away when (5) Assumed rainfall the banks of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Up to 153mm per hour and 690mm in 24 hours in the Shibuya, Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River Furukawa, Meguro, Nomikawa Rivers basin Shibuya River,Furukawa River System are eroded. -

No Time and No Place in Japan's Queer Popular Culture

NO TIME AND NO PLACE IN JAPAN’S QUEER POPULAR CULTURE BY JULIAN GABRIEL PAHRE THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in East Asian Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Professor Robert Tierney ABSTRACT With interest in genres like BL (Boys’ Love) and the presence of LGBT characters in popular series continuing to soar to new heights in Japan and abroad, the question of the presence, or lack thereof, of queer narratives in these texts and their responses has remained potent in studies on contemporary Japanese visual culture. In hopes of addressing this issue, my thesis queries these queer narratives in popular Japanese culture through examining works which, although lying distinctly outside of the genre of BL, nonetheless exhibit queer themes. Through examining a pair of popular series which have received numerous adaptations, One Punch Man and No. 6, I examine the works both in terms of their content, place and response in order to provide a larger portrait or mapping of their queer potentiality. I argue that the out of time and out of place-ness present in these texts, both of which have post-apocalyptic settings, acts as a vehicle for queer narratives in Japanese popular culture. Additionally, I argue that queerness present in fanworks similarly benefits from this out of place and time-ness, both within the work as post-apocalyptic and outside of it as having multiple adaptations or canons. I conclude by offering a cautious tethering towards the future potentiality for queer works in Japanese popular culture by examining recent trends among queer anime and manga towards moving towards an international stage. -

Homosexuality and Manliness in Postwar Japan

Homosexuality and Manliness in Postwar Japan Japan’s first professionally produced, commercially marketed and nationally distributed gay lifestyle magazine, Barazoku (‘The Rose Tribes’), was launched in 1971. Publicly declaring the beauty and normality of homosexual desire, Barazoku electrified the male homosexual world whilst scandalizing mainstream society, and sparked a vibrant period of activity that saw the establishment of an enduring Japanese media form, the homo magazine. Using a detailed account of the formative years of the homo magazine genre in the 1970s as the basis for a wider history of men, this book examines the rela- tionship between male homosexuality and conceptions of manliness in postwar Japan. The book charts the development of notions of masculinity and homo- sexual identity across the postwar period, analysing key issues including public/ private homosexualities, inter-racial desire, male–male sex, love and friendship; the masculine body; and manly identity. The book investigates the phenomenon of ‘manly homosexuality’, little treated in both masculinity and gay studies on Japan, arguing that desires and individual narratives were constructed within (and not necessarily outside of) the dominant narratives of the nation, manliness and Japanese culture. Overall, this book offers a wide-ranging appraisal of homosexuality and manliness in postwar Japan, that provokes insights into conceptions of Japanese masculinity in general. Jonathan D. Mackintosh is Lecturer in Japanese Studies at Birkbeck, University of London, -

Ginza Opens As Building, a Trend-Setting Retail Harvest Club

CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT 02 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT As a core company of the Tokyu Fudosan Holdings Group, 03 HISTORY OF TOKYU LAND CORPORATION We are creating a town to solve social issues through 05 ABOUT TOKYU FUDOSAN HOLDINGS GROUP value creation by cooperation. 06 GROUP’S MEDIUM- AND LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT PLAN 07 URBAN DEVELOPMENT THAT PROPOSES NEW LIFESTYLES 07 THE GREATER SHIBUYA AREA CONCEPT 09 LIFE STORY TOWN 11 URBAN DEVELOPMENT 25 RESIDENTIAL 33 WELLNESS 43 OVERSEAS BUSINESSES 47 REAL ESTATE SOLUTIONS Tokyu Land Corporation is a comprehensive real estate company the aging population and childcare through the joint development of with operations in urban development, residential property, wellness, condominiums and senior housing. In September 2017, we celebrated overseas businesses and more. We are a core company of Tokyu the opening of the town developed in the Setagaya Nakamachi Fudosan Holdings Group. Since our founding in 1953, we have Project, our first project for creating a town which fosters interactions 48 MAJOR AFFILIATES consistently worked to create value by launching new real estate between generations. 49 HOLDINGS STRUCTURE businesses. We have expanded our business domains in response to For the expansion of the scope of cyclical reinvestment business, changing times and societal changes, growing from development to we are expanding the applicable areas of the cyclical reinvestment 50 TOKYU GROUP PHILOSOPHY property management, real estate agency and, in particular, a retail business to infrastructure, hotels, resorts and residences for business encouraging work done by hand. These operations now run students, in our efforts to ensure the expansion of associated assets independently as Tokyu Community Corporation, Tokyu Livable, Inc. -

The Politics of Difference and Authenticity in the Practice of Okinawan Dance and Music in Osaka, Japan

The Politics of Difference and Authenticity in the Practice of Okinawan Dance and Music in Osaka, Japan by Sumi Cho A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jennifer E. Robertson, Chair Professor Kelly Askew Professor Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Markus Nornes © Sumi Cho All rights reserved 2014 For My Family ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my advisor and dissertation chair, Professor Jennifer Robertson for her guidance, patience, and feedback throughout my long years as a PhD student. Her firm but caring guidance led me through hard times, and made this project see its completion. Her knowledge, professionalism, devotion, and insights have always been inspirations for me, which I hope I can emulate in my own work and teaching in the future. I also would like to thank Professors Gillian Feeley-Harnik and Kelly Askew for their academic and personal support for many years; they understood my challenges in creating a balance between family and work, and shared many insights from their firsthand experiences. I also thank Gillian for her constant and detailed writing advice through several semesters in her ethnolab workshop. I also am grateful to Professor Abé Markus Nornes for insightful comments and warm encouragement during my writing process. I appreciate teaching from professors Bruce Mannheim, the late Fernando Coronil, Damani Partridge, Gayle Rubin, Miriam Ticktin, Tom Trautmann, and Russell Bernard during my coursework period, which helped my research project to take shape in various ways. -

Boys Love Comics As a Representation of Homosexuality in Japan

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt mál og menning Boys love Comics as a Representation of Homosexuality in Japan Ritgerð til BA-prófs í japönsku máli og menningu Brynhildur Mörk Herbertsdóttir Kt.: 190994-2019 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir Maí 2018 1 Abstract This thesis will focus on a genre of manga and anime called boys love, and compare it to the history of homosexuality in Japan and the homosexual culture in modern Japanese society. The boys love genre itself will be closely examined to find out which tropes are prevalent and why, as well as what its main demographic is. The thesis will then describe the long history of homosexuality in Japan and the similarities that are found between the traditions of the past and the tropes used in today’s boys love. Lastly, the modern homosexual culture in Japan will be examined, to again compare and contrast it to boys love. 2 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Boys love: History, tropes, and common controversies ....................................................................... 6 Stylistic appearance and Seme Uke in boys love ............................................................................ 8 Boys love Readers‘ Demography .................................................................................................... 9 History of male homosexual relationships in Japan and the modern boys love genre ...................... 12 -

Station Building) and Its Relation with Surrounding Land Value

Ekibiru (Station Building) and its relation with surrounding land value Thesis COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Urban Planning By Shuran Chen May, 2015 Abstract Japan’s railroad stations, called Ekibiru 駅ビル(Station Building), are not only the place for commuters to take train and/or subway but also the destination for people to shop, dine and spend time with friend and family, offices for workers and hotels for travelers. In Tokyo Metropolitan Area, Majority of railroad companies, including former public-owned now privatized East Japan Railway Company, Tokyo Metro, Tokyu Dentetsu, are enjoying profits.1 Study also shows that the latest Class A buildings have the tendency to be connected to railroad station and are mixed-use of office and commercial. 2 The study aims to gain a better understanding of whether or not Ekibiru (Station with mixed-use right on the top) has correlation with surrounding land value by using “before and after” land value data of 116 station areas and the ward that station located in. The result shows that while there are tendency that Ekibiru area has higher land value than Ward or City average compared with Station area without Ekibiru, there cannot be seen clear correlation between Ekibiru renovation and its effect on surrounding land value. 1 Railroad Sector Ordinary Profit Ranking (Heisei 24 (2012) – Heisei 25 (2013)), 業界 search.com 2 Real Estate Investment Report November 2012, Nissei Research 目次 Introduction ...................................................................................... 4 Definition ................................................................................................ 4 Background .............................................................................................. 4 Hypothesis and Research Question ............................................................ 6 Methodology, process and Data .........................................................